I always enjoy returning to a subject that connects us to my forthcoming book Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? A Walking Tour of Nazi Occupied Paris (1940−1944). Today, you will meet someone who was born during the latter part of the 19th-century. The men and women born just before the dawn of the 20th-century were an interesting group. They were heavily influenced by three principal world events: World War I, the Bolshevik/Russian Revolution, and the Great Depression. No one was influenced more than the first and only American who became mayor of Paris: William Christian Bullitt Jr. (1891−1967).

Did You Know?

On 14 June 1940 as the Wehrmacht marched triumphantly into Paris and turned down the Avenue des Champs-Elysées, a young German officer watched in disgust. Later, Count Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg relayed his feelings to General Franz Halder. The 33-year-old officer told the general and others that Hitler deserved to die. He was advised to keep his feelings to himself because as long as Hitler’s military victories continued, Germans would never support a coup. Four years later on the morning of 20 July 1944, Stauffenberg tried unsuccessfully to assassinate the Führer. He and many of the other ring leaders were captured, tortured, and executed for their part in the plot. The initial planning of the operation took place years earlier in Paris at the Hôtel Continental. It is one of the stops in first volume of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?

William C. Bullitt

Despite being born in Philadelphia to a very rich and pedigreed family (his ancestors included Patrick Henry and Pocahontas), Bullitt grew up in Europe. He was fluent in French and German. His maternal side was German and Jewish and his mother spoke French at home. After graduating from Yale University (and dropping out of law school after his father died), Bullitt became a correspondent for the Philadelphia Public Ledger and covered World War I events in Russia, Germany, Austria, and France. After the United States entered the war, Bullitt worked for the State Department and their intelligence service where he was noticed by President Woodrow Wilson. He was picked by Wilson to attend the 1918 Paris Peace Commission but subsequently resigned in protest over the terms of the Treaty of Versailles (his testimony before Congress helped defeat the treaty).

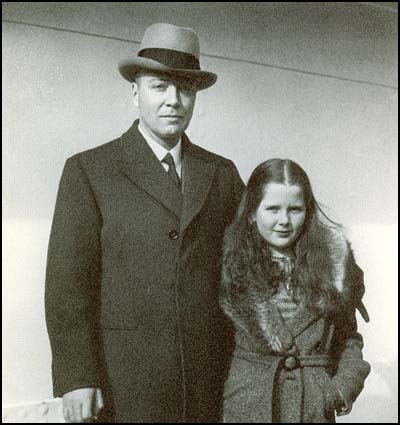

Bullitt’s second wife, Louise Bryant (1885−1936), was a journalist who wrote Six Red Months in Russia. She had been married to the radical journalist John Reed until his death in 1920. Bullitt had been good friends with Reed and in 1924, married Reed’s widow. Their marriage lasted only six years before he filed for divorce—he alleged his wife was having an affair with another woman. Bullitt gained custody of their only child, Ann (1924−2007). The story of Louise and John Reed is told in Warren Beatty’s 1981 movie Reds.

Bullitt became close friends with Franklin Delano Roosevelt and when Roosevelt became president in 1933, Bullitt was named as the first ambassador to the Soviet Union (Watch William Bullitt arrive in Moscow here.) During Wilson’s administration, Bullitt had gone on a special mission to negotiate diplomatic relations between the United States and the new Bolshevik regime. Roosevelt felt that Bullitt had made a favorable impression on the Bolshevik leaders to the point where they would accept him as ambassador. Despite his initial support of the revolution and the Soviet Union, Bullitt became disenchanted with Stalin and his government (Watch Bullitt’s speech here.) He remained ambassador until 1936 when Roosevelt brought him back and assigned Bullitt to France as ambassador.

Appointment to Paris

Bullitt was extremely suited for being ambassador to France. It was almost like his entire career up to that point had been a dress rehearsal for this position. Bullitt, a Francophile, dressed well, fed his guests with the best French cuisine, served them the finest French wines, rented the beautiful Château de Vineuil-Saint-Firmin for weekend entertaining in Chantilly, and spoke flawless French, especially while flirting with the women. No wonder the Parisians loved him. Watch Bullitt dedicate a monument to the American troopers who landed in 1917 here.

Bullitt was a tireless negotiator for American interests in Europe as well as supporting the French in Washington. French politicians such as prime ministers Léon Blum and Édouard Daladier, liked him, trusted him, and confided in him. The American ambassador attended most of the French cabinet meetings to the point where the French press called him a “minister without portfolio.” He championed the cause back in Washington for more planes, ammunition, and artillery for the French military. Bullitt hated the Nazis and Hitler knew it. The Nazis considered Bullitt and ironically, Joseph Kennedy (ambassador to England), to be the two American ambassadors with the greatest hostility towards Germany.

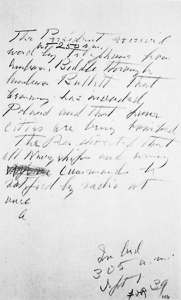

President Roosevelt learned the Germans had attacked Poland from Bill Bullitt. Woken by the phone call on 1 September 1939 at 2:50 A.M., Roosevelt wrote down the circumstances on a note pad he always kept on the night stand next to his bed.

The Battle of France

There were very few realists left in France by 1939 and early 1940. Bullitt, Charles de Gaulle, and the French Prime Minister, Paul Reynaud knew the Germans would successfully attack France. Ambassador Bullitt began sending Roosevelt numerous cables outlining his prophecies. The president ignored them because he thought Bullitt’s ideas were “too pessimistic.” Too bad because Bullitt was very perceptive and in most cases, he was correct. Eventually, Roosevelt would look back and conclude his friend, Bill Bullitt, had been right.

One of these prophecies came true in May 1940 when the Germans overran the low countries, bypassed the Maginot Line, and proceeded to cross over the border of France. As they pushed south, the Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe managed to corner the forces of the British and French onto the beach at Dunkirk. Between 26 May and 4 June, approximately 338,000 men were evacuated. However, 40,000 French soldiers never made it onto one of the “little ships” and were captured along with 45,000 other French soldiers who were defending the perimeter. These men became part of the two million French soldiers held as prisoners until the end of the war. Read the story of one of the soldiers here.

Evacuation of Paris

As the Germans marched on Paris, almost all of the city’s citizens began to voluntarily leave by car, bike, or foot (read the story of Etta Shiber here). On 10 June 1940, the French government left Paris for Tours. Only the American Embassy, French military headquarters, and the Prefecture of Police remained in the city as the only official government operating organizations. The following day there were only two: police/fire and the American Embassy as the French military began to evacuate Paris.

President Roosevelt ordered Bullitt to leave and follow the French government to Tours or wherever it went, however Bullitt refused and decided to remain in Paris. The ambassador knew that if the city was to be spared the same outcome as Rotterdam or Warsaw (the cities were flattened by the Nazi blitzkrieg), he needed to be there to negotiate with the Germans. Again, Bill Bullitt was correct.

Paris Is Declared An Open City

Prime Minister Reynaud and Interior Minister Georges Mandel appointed Bullitt as the provisional mayor of Paris on 12 June 1940. Reynaud told Bullitt that his government had agreed to allow Paris to become an “open city.” In other words, Paris waived its right to resist in exchange for a peaceful occupation. Bullitt sent an emissary to the German commander proposing the “open city” concept.

The German army was on the northern outskirts of Paris in Saint-Denis when they were fired upon. This angered General von Küchler and he gave the orders to his artillery and aviation units to bomb Paris (von Küchler was the commanding officer who leveled Rotterdam exactly one month earlier). When this news reached the American ambassador, he phoned his friend and colleague in Berlin, Ambassador Hugh Wilson, and requested he talk to the Germans and have them honor Paris as an “open city.” Von Küchler’s orders were retracted and Paris was saved. It is likely that had Bullitt left the city as Roosevelt demanded, Paris would have suffered the same fate as Rotterdam.

The Germans left many American organizations alone during the four years of the Occupation. These included the American Hospital of Paris (Neuilly), the American Library of Paris (9, rue de Téhéran), and the American Cathedral (23, avenue George V). During the time America was still neutral, Bullitt persuaded the Germans to respect the property rights of the roughly 2,500 Americans who remained in the city. The embassy issued hundreds of certificates which could be attached to private property identifying its owner as an American. These were critical as the Nazis began to confiscate Jewish personal property.

Bullitt’s Downfall

William Bullitt resigned as ambassador to France in November 1940. Right about this time, Roosevelt was being pressured to appoint Bullitt as the next secretary of state. The president refused as he thought his friend was “too quick on the trigger” and “talked too much.” Despite continuing their discussions, Roosevelt was clearly becoming annoyed with his friend.

Turning down the ambassadorship to Britain, Bullitt accepted an advisory role to the president, specifically focusing on North Africa and the Middle East. By doing so, Bullitt hoped to eventually gain a cabinet position. Unfortunately, he was not aware that he had fallen from Roosevelt’s grace.

Several events hastened Bill Bullitt’s downfall. He had earlier courted the president’s long-time secretary, Margaret LeHand, whom Roosevelt wanted his friend to marry. When this didn’t happen, Bullitt dropped a notch. In April 1941, Bullitt presented Roosevelt with evidence that the Undersecretary of State, Sumner Welles had made homosexual advances to several railroad porters. It happened that Welles was Roosevelt’s best friend and the president dismissed Bullitt’s allegations. However, by 1943 and under pressure, Roosevelt removed Welles from his position within the department of state. Roosevelt also never forgave his former French ambassador for not following the French government—this was seen by many (including the president) as an act of insubordination. All of these (and other issues) added up to Roosevelt never appointing his former friend to any future government post. After Roosevelt died, the new Truman administration did not have any room for Bill Bullitt and neither did the Eisenhower administration.

Back to Philadelphia

Bullitt returned to Philadelphia in 1943 to run for mayor on the Democratic ticket. He never stood a chance. His Republican opponent was the acting mayor and the last time the city had a Democratic mayor was 1884. The grass roots reason for his defeat was that Roosevelt told the city’s Democratic leaders to “cut his (Bullitt) throat.” By 1948, Bullitt had changed his party affiliation to Republican (I suppose his anti-communist views meshed better with the Republicans).

Five weeks before D-Day (6 June 1944), Bullitt tried to join the United States army. After his application was rejected, Bill Bullitt contacted his old friend, Charles de Gaulle, and was gladly accepted into the French army. He became a commandant (major) serving in the headquarters of General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny (read about the General here). Bullitt’s goal was to fight and he was right in the middle of some of the fiercest fighting between D-Day and V-E Day (Victory in Europe Day; 8 May 1945). In honor of Bullitt, de Tassigny formed the “Second Shock” Battalion in January 1945. It carried Bullitt’s initials “WB” and the battalion flag had the picture of Philadelphia’s Liberty Bell on the tricolor flag. On the first anniversary of the liberation of Paris (25 August 1945), Bill Bullitt sat next to General de Tassigny in the lead car of the victory parade down the Avenue des Champs-Elysées.

Post-French Liberation

Bullitt took leave of the French First Army in October 1944 and flew to Paris for the purpose of opening the American Embassy. In full French uniform, he stepped out onto the front balcony where the crowd wildly cheered for him. He jokingly commented on how they must have mistaken him for General Eisenhower as they were similar in size and had the same baldness.

Bullitt rejoined his unit and fought with them until the end of the war. After the war, he was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Legion of Honor. He died of cancer in February 1967 at the American Hospital of Paris without ever attaining the position he coveted for more than thirty years: United States Secretary of State.

Later Years

One of Bullitt’s strengths was his ability to analyze international relations and consequences of international relations and political entailments. This was true with his criticism of the Treaty of Versailles which he saw the terms as being too harsh. Bullitt warned his superiors of what he saw as future consequences to Europe and the world: a rising nationalist movement in Germany. During his stint as the ambassador to the Soviet Union, Bullitt warned Roosevelt about Stalin but was rebuffed. Bullitt wrote a report in the 1930s that when read today sounds very prophetic and almost lays the foundation for the Cold War attitude twenty years later. Bullitt’s successor in Moscow, Joseph Davies, took the complete opposite stance. He was advising Roosevelt that Stalin and Russia were friends and could be trusted. Roosevelt listened to Davies. By 1938, Bullitt learned about the pending Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. Warning Washington, Bullitt once again found the president would turn his back to him. Roosevelt was tired of Bullitt’s constant memos which seemed to contradict everyone else.

Another Couple of “Did You Know?”

For those of you who know the story of Alger Hiss, it was the French prime minister, Édouard Daladier, who alerted Bullitt to the fact that Hiss, an employee of the U.S. State Department, was working for Soviet intelligence. Bullitt passed this information on to Hiss’s superior. It would be the Hiss affair in the 1950s that sparked the careers of a future president, Richard Nixon, and the Communist baiter, Senator Joseph McCarthy.

My maternal grandfather was asked to run for governor of Michigan in the 1940s. They told him he would have to run on the Democratic ticket. The problem was Gramps was a Republican. You see back then, only Democrats were getting elected to public office because of Roosevelt’s popularity. Well, Gramps refused and they picked another man to run instead. He was a Republican but either was a pragmatist or had no scruples and he switched parties. He won.

Recommended Reading

Etkind, Alexander. Roads Not Taken. An Intellectual Biography of William C. Bullitt. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017.

Glass, Charles. Americans in Paris: Life & Death Under Nazi Occupation. London: Penguin Books, 2009.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are waiting anxiously to move into our new home here in Punta Gorda. It’s about two months away from being completed. In the meantime, I’m working on future blogs as well as the first volume of the next book. Summer is right around the corner and we’ll soon be in air conditioning 24/7. But this time of year is great pool and beach weather here in Florida. We’re hooked on going up to a Venice beach where you can hunt for shark’s teeth in knee deep water.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

We’ve made many new friends from all over the world after receiving their interesting e-mails. One of these came to us just the other week from our new friend, Ann U. Her e-mail and request has stimulated an interesting project for us.

Ann’s father was a top turret gunner in a B-17 during World War II. On 29 May 1943, his plane was hit by German flak over western Normandy in France. The plane broke in two but not before at least nine of the ten-man crew bailed out. Her father was captured and spent four months in Paris as a “guest” of the Gestapo. Unable to break him, the Gestapo sent him to Dulag Luft 12 located in what today is Tychowo, Poland.

The reason Ann contacted us was to find out if we might know where a particular Gestapo cell was located in Paris. Her father told her he carved his name into the wall of his cell. Ann wanted to find it so she could travel there and see it. I wrote back to her saying it would be nearly impossible to locate it because of the numerous locations of Gestapo torture sites and cells that no longer exist. I indicated that I only knew of one building where we could get in to view one or two cells: The Ministry of the Interior.

To my surprise, within minutes of sending that e-mail to her, Ann responded with the news that it was the Ministry where her father’s cell was located. Raphaëlle is bird-dogging her contact at the Ministry of the Interior to see if we can locate her father’s signature.

Our next blog will be the full story of Ann’s father and his role in World War II and beyond. I hope you’ll continue to follow our blogs but especially the March 31st blog on Ann’s father.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2018 Stew Ross