The longer one spends in Paris (or any city for that matter), certain questions ultimately arise over innocuous issues. Sandy and I are interested in the history of the City of Light and over time we notice little things that lead to more questions. For example, after multiple trips to Paris to research our first two books (Where Did They Put the Guillotine? Volumes 1 & 2 ), it occurred to me that there were no major statues commemorating the French Revolution or the revolutionaries (other than Danton’s statue or several located in the exterior alcoves of city hall). I found old postcards showing photos of statues dedicated to the revolution, but they are all gone now. Why? I found the answer while researching the current books on the German occupation of Paris (Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? ). During the occupation, the French melted down most of the bronze statues to provide ingots that were used to repay German reparations and cover the cost of the occupation forces. (Click here to read the blog, Statuemania.)

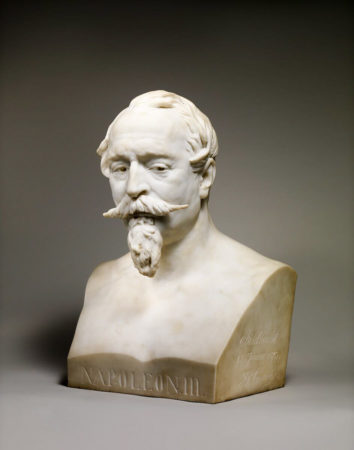

Today’s topic deals with a similar type of issue but I’m not sure I have found the answer to my question. During the mid-19th-century, Paris was “reborn” when it was transformed into a modern city by Emperor Napoléon III and his préfet, Baron Georges Haussmann. Over a period of 17-years, day and night demolition and construction created the city we all love today. The wide avenues, homogenous architecture known as Haussmann buildings, and beautiful parks are all sights we can identify with and enjoy. However, there are many other infrastructure improvements, some visible and some not, that Napoléon III was responsible for initiating.

Considering the immense contributions by the emperor, I wonder why there are no memorials, statues, or commemorative plaques to Napoléon III. The city’s transformation did not come cheap. There were considerable costs with ramifications that can still be felt more than 170-years later. Have the French not forgiven Napoléon III for these negative costs or maybe perhaps, that he lost a war to the Prussians?

(This blog is based on my two-hour lecture, The Destruction and Renovation of Nineteenth Century Paris.)

Did you Know?

Did you know that Notre Dame is beginning to give up some of its secrets? During the recent efforts to save the cathedral after the devastating fire in April 2019, two lead sarcophaguses were discovered buried beneath the nave. One contains the remains of a high priest, Antoine de la Porte, who died on Christmas Eve 1710 at the age of eighty-three. The occupant of the second sarcophagus was likely a young, wealthy, and privileged noble from the 14th-century. (He was in his 30s and based on the pelvic bones, considered to be an expert horseman.)

Their remains were located about one meter (3.3 feet) below the cathedral floor. However, there were other items found at a lesser depth. These buried treasures included statues, sculptures, and fragments of the cathedral’s original 13th-century rood screen.

As I’ve said before, one of the world’s greatest museums lies twelve feet below the surface of Paris but the French do not take too kindly to people digging up their city. Archeological finds are normally found only when basements are renovated or associated with construction on métro stations. (Please note that the remains of the two men are not considered “archeological objects” and will be returned to the Paris cultural ministry for proper burial.) France’s national archeological institute, Inrap, is responsible for the dig at Notre Dame and the objects found there.

For additional reading, please refer to my past blogs, Stop the Presses: Skeletons and Not Buildings (click here) and Paris Digs (click here).

Medieval Paris

Founded in the 3rd-century by the Parisii tribe, Paris was originally settled by the Romans in 52 B.C. on what we call today, the Left Bank (the Right Bank was marshland). The city was then known as Lutetia. Other than an old arena, several remnants of the city’s Roman aqueduct system, and some odds and ends, there is no evidence of the Roman settlement. The two best sites in Paris to experience medieval life is to visit the Musée national du Moyen Âge Paris, or Musée de Cluny and the Crypte archéologique de l’île de la Cité, or the Archeological Crypt. (The Panthéon sits on the site of the ancient Roman forum.) Read More The Missing Emperor