Those of you who have been long-time readers of my blogs know that I like to highlight women who were significant to the historical periods I write about (e.g., Medieval Paris, French Revolution, and now, World War II and the Occupation of Paris). So many of these women are overlooked for their roles and accomplishments.

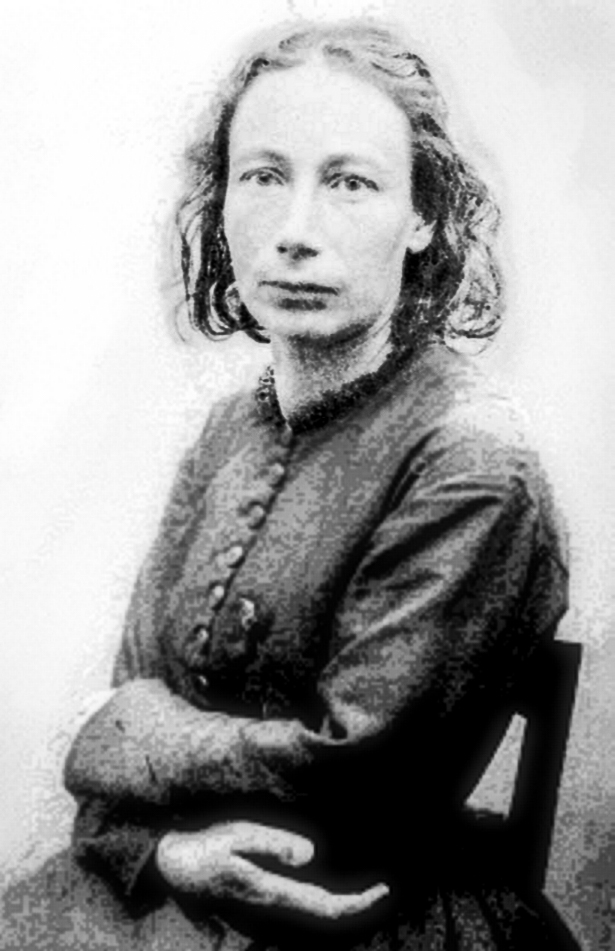

Today, you will be introduced to a woman who was considered a revolutionary as well as an anarchist. Over her lifetime, Louise Michel was given many nicknames: La Louve rouge (the red she-wolf), the “French grande dame of anarchy,” and la Bonne Louise (the good Louise). But it was “The Red Virgin” label which most people knew her by. Michel was a sought-after speaker, a playwright, an author, and a well-known advocate for women’s rights including education and property rights.

Did you Know?

Did you know that Queen Elizabeth II’s profile faces right on every coin she’s featured on? The tradition is to reverse the profile with each succeeding reigning monarch. So, going back to Queen Victoria, her profile faces left while her son, Edward VII (r. 1901-1910), faces right. His son, George V (r. 1910-1936), looks to the left, but his successor, George VI (r. 1936-1952) also faces to the left. Did George VI (Queen Elizabeth II’s father) break tradition? Not really. It was Edward VIII who chose to break tradition and during his short reign (eleven months; he abdicated in December 1936), the coins were minted with his profile facing left. After the abdication, George VI took the view that his brother’s profile should have been to the right and as such, opted to continue the tradition by facing left. His daughter carried on the tradition and her profile is to the right.

Let’s Meet Louise Michel

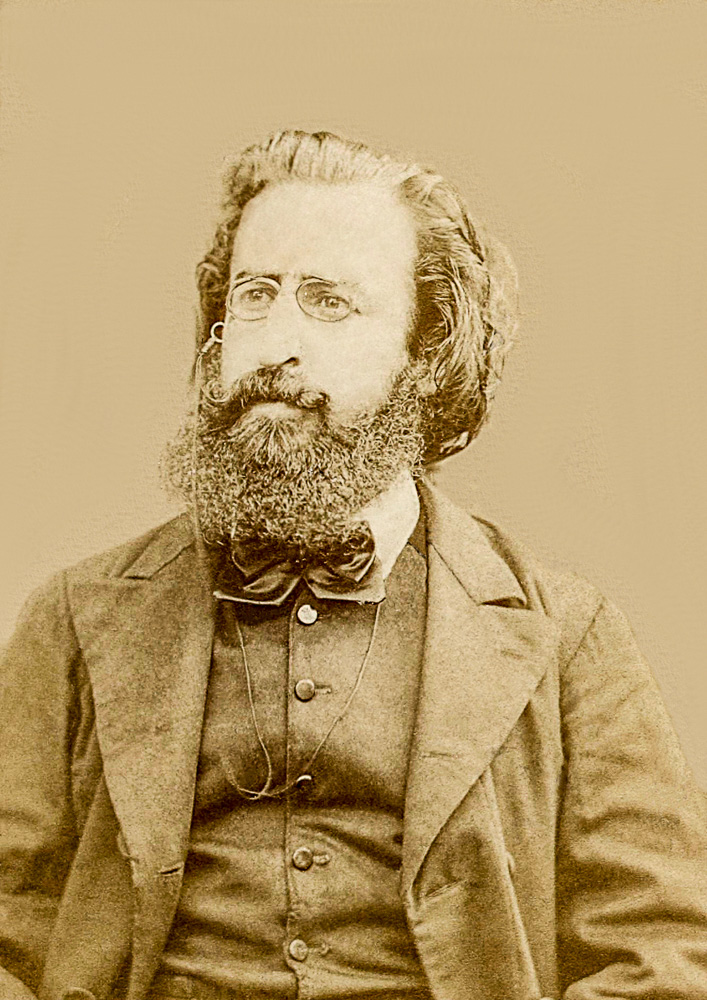

Louise Michel (1830-1905) was the illegitimate daughter of a maid. Coincidentally, she was born in the year when the citizens rose to depose the last Bourbon king, Charles X. Raised by her grandparents, Louise received an excellent education and ultimately became a teacher. In 1865, she opened a progressive school in Paris and began to associate with radical members of society including Théophile Ferré. By this time, Napoléon III and his Second Empire ruled the country and as the years went on, general dissatisfaction with the emperor grew.

The Paris Commune

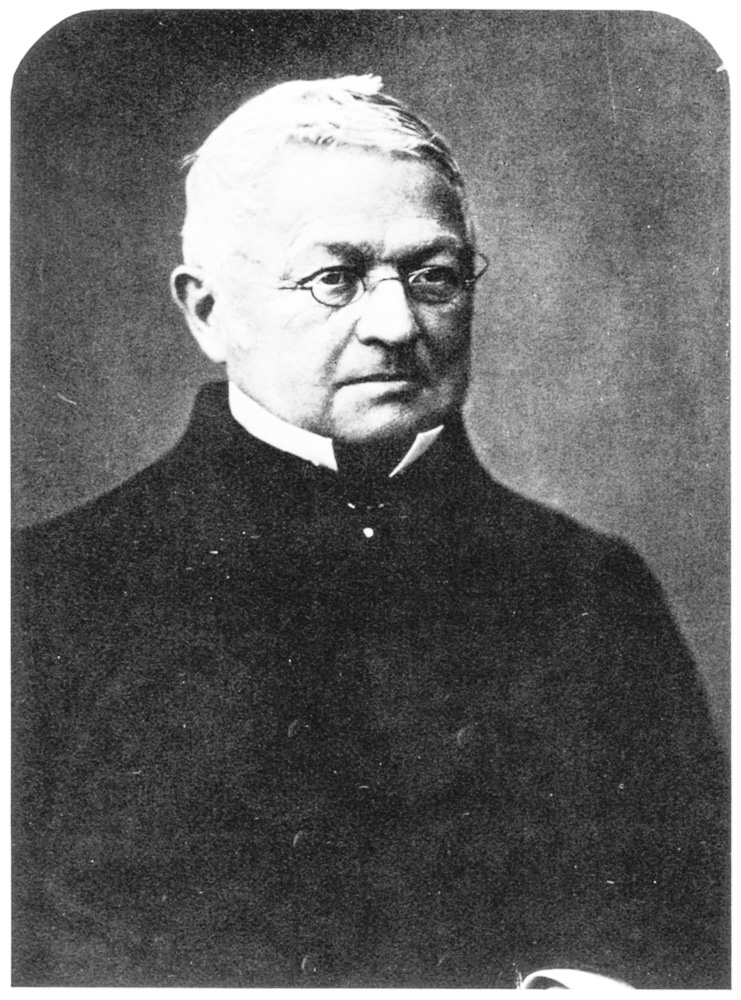

Napoléon III waged war against the Prussians and their allies in what is known as the Franco-Prussian War. On 2 September 1870, Napoléon III lost the war and was taken prisoner. Two days later, the citizens of Paris became agitated and a prominent radical politician, Léon Gambetta (1838-1882), proclaimed the establishment of the Third Republic. Gambetta, a radical Republican, was defeated in the election to lead the government by the monarchist, Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877). At this point, every anarchist, leftist, and extremist crawled out of the woodwork ⏤ including Louise Michel. There was no way they were going to allow France to return to a monarchy.

Beginning on 19 September 1870, the Prussian army surrounded Paris and began a siege of the city. The siege lasted until 28 January 1871 when the government agreed to an armistice. There were new elections for a National Assembly and the conservatives and monarchists were returned to power with Thiers given executive powers. The people were upset and did not trust Thiers. The working-class neighborhoods including Montmartre and Belleville began to get very angry and agitated (these two villages were part of what was referred to as “the Red Belt” around the perimeter of Paris). To make matters worse, Thiers moved the government out of Paris to Versailles, the icon of the Bourbon monarchy.

On 17 March 1871, Thiers began to move against the Paris militants. Despite the French army not being allowed to carry weapons (as part of the armistice terms), the National Guard got to keep their guns and cannons. Thiers sent the National Guard to the hills of Montmartre and Belleville to retrieve their cannons. Many of the members of the National Guard had been radicalized and on 18 March, they refused to take the cannons away from the militants. Louise Michel later said, “The eighteenth of March could have belonged to the allies of Kings, or to foreigners, or to the people. It was the peoples.”

Louise Michel joined the radicals in the National Guard. She was elected to lead the Montmartre Women’s Vigilance Committee. In that role, Louise was thrust into a revolutionary leadership role in what became known as the Paris Commune and the participants were referred to as Communards. She aligned herself with the two most violent Communards, Ferré and Raoul Rigault. Louise ended up joining and fighting with the 61st Battalion of Montmartre. She later admitted that she “liked the smell of gunpowder, grapeshot flying through the air, but above all, I’m devoted to the Revolution.” Louise fought alongside the men as well as the women who manned the barricades. She said, “It is true, perhaps, that women like rebellions. We are no better than men in respect to power, but power has not yet corrupted us.”

The next six weeks saw bloodshed on both sides as Thiers sent his troops into the city to squash the insurrection. The Communards burned down and destroyed many buildings including the Hôtel de Ville (city hall) and the Tuileries Palace. The fighting reached its peak starting on 21 May 1871 and lasted the seven days known as “Bloody Week.” During this time, massacres occurred, executions were carried out, and on the final two days, at the last strongpoint of the Communards, Père Lachaise Cemetery, more than 150 of the surviving National Guardsmen were lined up along a wall and shot by Thiers’s soldiers.

Arrest, Trial, and Deportation

Most of the Communards were killed or executed (20,000 is the estimated number of summary executions) while the survivors were arrested and tried, including Louise. She dared the judges to sentence her to death for charges of trying to overthrow the government, encouraging citizens to arm themselves, and for using weapons and dressing in a military uniform. Along with around 10,000 other Communards, Louise was deported to New Caledonia where she remained for seven years.

Back to France

A general amnesty was granted in 1880 to all of the surviving Communards. Louise returned to France and picked up where she left off almost ten years earlier. However, this time, she was a committed and experienced anarchist and revolutionary. Louise began giving speeches, led demonstrations waving a black flag (the symbol of anarchism), and incited riots for which she was tried and spent six more years in prison but this time, entirely in solitary confinement. After her release in 1886 and never one to back off, Louise was arrested once again in 1890. Louise was committed to a mental asylum but escaped to London where she joined the European anarchist circles and continued agitating through her speeches. By 1895, Louise had returned to France for the last time. While she continued writing and speaking, Louise was on relatively good behavior as evidenced by the fact she stayed out of jail for the remaining ten years of her life.

Louise Michel’s political spectrum changed throughout her adult life. Starting with progressive politics, her views morphed into revolutionary Socialism, and finally, radical anarchism.

Merriam-Webster defines an anarchist as a person who rebels against authority, established order, or ruling power. Also, one who uses violent means to overthrow the established order. I’ve always used the example of an anarchist as someone who willingly runs a red light because it’s a symbol of authority and established rules don’t apply to them.

As far as the violent means part of the dictionary’s definition, Louise started a school in London with teachers who were exiled anarchists. When the school was closed in 1892, the authorities found explosives in the basement.

Louise Michel is buried in the Levallois-Perret Cemetery in Paris near her fellow Communard, Théophile Ferré who was executed. Her grave is attended to by members of the community.

Recommended Reading and Viewing

Merriman, John. Massacre: The Life and Death of the Paris Commune. New York: Basic Books, 2014.

If you’re interested in learning about the Paris Commune, you can’t do better than Mr. Merriman’s book. It’s an enjoyable read and doesn’t get bogged down like other history books. He keeps the narrative moving and you’ll get absorbed into the motivations of the main players.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew

We are very excited about the covers for our next three books: Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? A Walking Tour of Nazi Occupied Paris (volumes one and two) and Where Did They Bury Jim Morrison, the Lizard King? A Walking Tour of Curious Paris Cemeteries.

Sandy has posted the covers in our web site so; I urge you to take a look. If you have any comments or suggestions, please don’t hesitate to contact us. By no means are these covers cast in concrete at this point.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thank you to Dawn C. for reaching out to us concerning a blog I wrote in 2016. It was about One-eyed Kate (read here). If you remember the blog or, page 77 of Where Did They Burn the Last Grand Master of the Knights Templar? Volume Two, you will recall me mentioning there is a cellar in the building built in 1585. Well, Dawn was working in Paris as a nanny (jeune fille au pair) when she and a group of friends had access to the building. They found the hole and went down into the basement to party all night. There was a dirt floor and tunnel which led them to the wine “caves” with twenty-five-foot ceilings. Someone strung up lights, set up the stereo (for you young people, that’s a machine we used to play records on), and danced the night away. It sounds like a great memory! I hope she and her friends eventually found the secret entrance to the Catacombs and partied down there as well.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you. The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We need your help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs. Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright ©2019 Stew Ross

While hardly meaning to quibble with Merriam, not all anarchist are or were fans of violence. [Nor do we all run red lights, all the time…:-)) ]

Enjoyed finding your blog. Have subscribed, and look forward to further interesting reading.

Hi Thom; Thanks for your comments. I always enjoy someone with a sense of humor. As far as Merriam, I only report the “news.” As far as the “running the red light,” that was a comment someone said to me a long time ago (probably in a political science class). It has stayed with me since then. Thanks very much for subscribing to the blog. Sounds like you are an anarchist. Is there any famous anarchist you’d like to see highlighted in a blog (besides yourself)? Ha ha. Hope we hear from you again. STEW