My aunt and three uncles served in World War II. Aunt Marge was a lieutenant and nurse who followed the 6 June 1944 invasion forces into Europe. Uncle Pete was an army sergeant serving in the Pacific Theater while Uncle Bill was the naval commander of a mine sweeping vessel in the Pacific. My mother’s only brother, Hal, enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Force in 1942. He was a young P-47 Thunderbolt fighter pilot in Europe and completed 97 missions. Hal’s missions were primarily over Italy and then Germany. His primary responsibilities included destroying enemy assets such as rail lines, depots, manufacturing, or any target deemed necessary for destruction.

By August 1945, Germany and Japan had surrendered. More than 12.0 million American service men and women spread across 55 theaters of war needed to get home. One of the many vessels used to return them to the United States was the ocean liner, RMS Queen Mary. Stripped of its luxury furnishings and non-essential items, the ship was painted grey in 1939 and used as a transport ship.

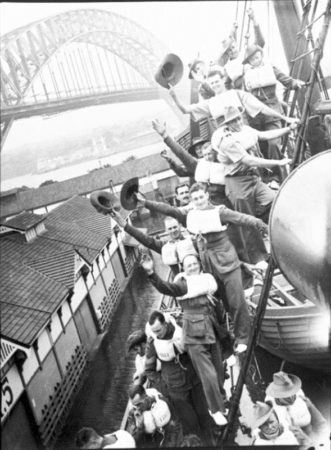

Uncle Hal and 810,000 U.S. military personnel returned to America aboard the Queen Mary otherwise known as “The Grey Ghost.”

My aunt and uncles along with millions more like them came home and went on to become known as “The Greatest Generation.”

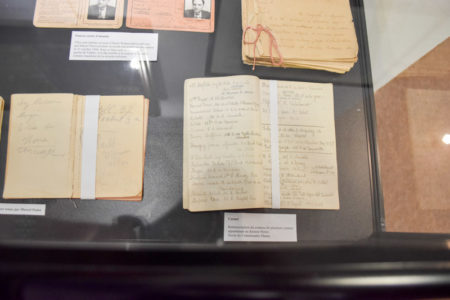

REVOLUTIONARY PARIS – Volume One & Volume Two

These books are about Paris. They are about the places, buildings, sites, people, and streets that were important parts of the French Revolution. You are about to enter a journey into history beginning in 1789 at the village of Versailles with the procession of the Estates-General and ending on the Place de la Révolution with the execution of Maximilien Robespierre on 28 July 1794. This is your personal walking tour of the French Revolution as it occurred in Paris and Versailles.

Did You Know?

Did you know that an urban model for mixed-use residential, commercial, and parks is being developed? It is called the “15-minute city” and is based on one’s ability to get to the shops and parks within a 15-minute walk from your residence. Scholars at Massachusetts Institute of Technology are researching, quantifying, and measuring the “urban fabric” to see if this model can become a reality. As you may suspect, there are those who enthusiastically support an urban model like this while others bemoan the likely demise of the automobile.

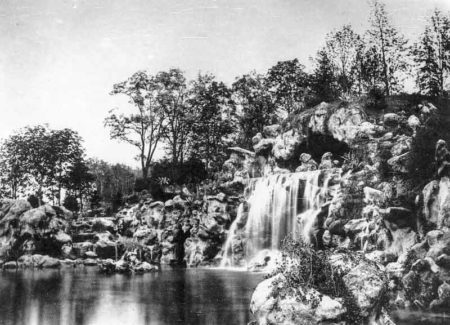

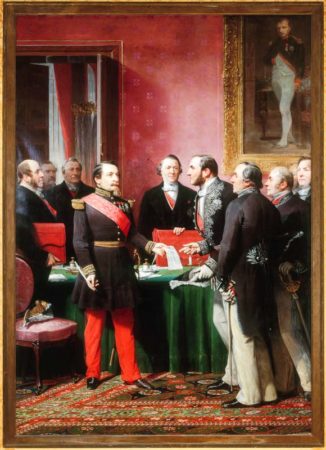

For those of you who have traveled in Europe, you are undoubtedly familiar with a city that was transformed in the mid-19th-century into a “15-minute walking city.” It is Paris. Napoléon III’s primary instruction to Baron Haussmann was to ensure every citizen could reach a park within a 15-minute walk. Prior to the seventeen-year “destruction and reconstruction” of the city, only forty-eight acres of parks existed. After 1870, more than 5,000 acres of new or expanded parks and twenty-four new squares were being enjoyed by the Parisians. Napoléon III’s goal of a “15-minute walkable city” had been achieved.

So, why spend millions and millions of dollars on studies when we can see and experience a contemporary example of the “15-minute city”? It does work.

Our next blog will be an expanded reprint of Charles Marville and le Vieux Paris.

(Click here to read The Missing Emperor and here to read Paris Digs.)

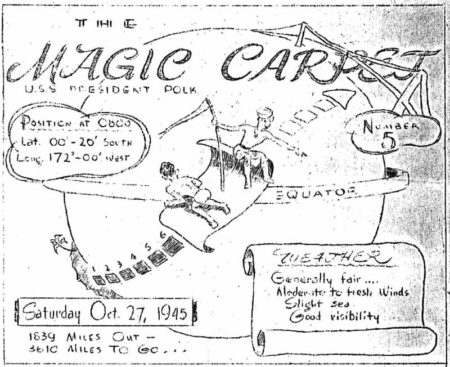

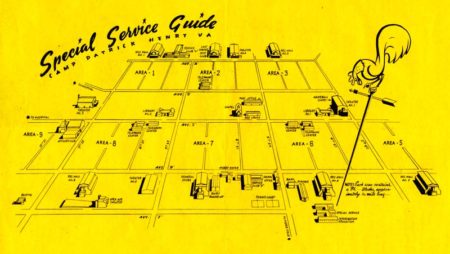

Operation Magic Carpet

By mid-1943, Gen. George C. Marshall (1880−1959), Army Chief of Staff, and others were sufficiently convinced Germany would ultimately be defeated. The general, a World War I veteran, was determined to avoid a similar demobilization debacle the army experienced in 1918-1919. However, twenty-five years later, he was faced with the same logistic issues but on a larger scale: how to get millions of service personnel back to the United States in a timely, orderly, and fair manner. He really couldn’t bring the men and women home until both Germany and Japan had surrendered. So, in July 1943, Gen. Marshall tasked the War Shipping Administration (WSA) to come up a plan for demobilization addressing which soldiers would remain in Germany, which soldiers would be sent to Japan to fight and finally, who would be the lucky ones to go home. The WSA was responsible for developing and coordinating the plan called “Operation Magic Carpet.”

Operation Magic Carpet officially commenced on 6 September 1945, four days after Japan surrendered and it ended 360-days later on 1 September 1946. At the time of Japan’s surrender, about 12.2 million men and women were serving in the American military (compared to 334,000 in 1939). Of these, about 8.0 million personnel were stationed overseas in the army, army air forces, navy, marines, and coast guard. Over the one-year existence of Operation Magic Carpet, about 22,222 American service personnel per day were delivered to their homes.

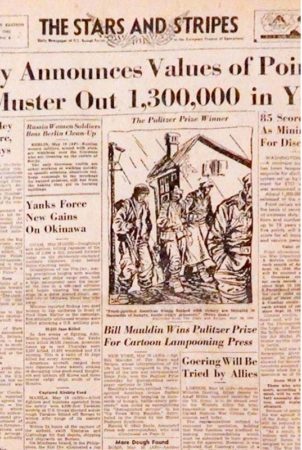

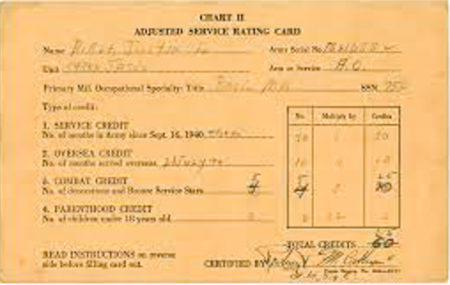

While getting these men and women home became top priority once the war was over, the biggest question was how to assign individual priorities for shipping out. The War Department came up with what they thought was an equitable point system called the “Adjusted Service Rating Score.” A total of 85 points was necessary to become eligible to return home. Women in the Women’s Army Corps were eligible with 44 points while officers were not included in the point system. A substantial number of military personnel were required to remain in Japan and Europe as occupation forces and four categories were established. Category One consisted of units to remain in Europe (eight divisions: 337,000 personnel). Category Two became the units deployed to fight in Japan (1.0 million men). Category Three were men and women retrained for reassignment to categories one and two. Category Four were the lucky ones. They got to go home.

Under the point system, every soldier (I’ll use this term to mean all those eligible for consideration) received a number of points based on how long they had been overseas (one point for each month of service plus an additional point for each month overseas), how many decorations were awarded to them for valor or merit (five points per medal including the purple heart), how many campaigns they fought in (five points for each campaign), and how many children they had back home (twelve points for each dependent child up to a maximum of three children).

From the time the point system was announced in September 1944 until hostilities ceased, American service personnel kept close track of their point totals. At that point, combat personnel anxiously awaited news announcing which units were officially credited with a campaign, citations to be awarded individually or to the unit, and then had an officer certify their number after surpassing eighty-five. As expected, the system created just as many unhappy soldiers as there were happy ones. Despite being straightforward, the points system was not perfect or always fair. It was an administrative nightmare, and the soldiers found many faults with the system. Eventually, the military revised and lowered its projected needs for overseas personnel and the total points required to come home dropped from 85 to fifty.

By the end of 1945, about four million people had returned to the United States. After the Japanese surrendered, the navy authorized combat ships (i.e., carriers, battleships, and smaller vessels) to join the civilian ships and begin transporting soldiers. The point system was discontinued in June 1946 and replaced with a two-year service requirement.

Click here to watch the video The Great Migration: The Story of Operation Magic Carpet.

RMS Queen Mary

The RMS Queen Mary (not to be confused with the contemporary Queen Mary 2) is a retired British (Cunard) ocean liner. It operated from 1936 until 1967 sailing primarily between Southampton and New York. It was built specifically for transatlantic voyages and the resultant rough seas. The ship’s gross tonnage is 81,237 with a length of 1,019 feet and a beam of 118 feet. It has twelve decks and a height of 181 feet. (For comparison purposes, the new Royal Caribbean cruise ship, Icon of the Seas, has a gross tonnage of 248,663, 1,197 feet in length and a beam of 160 feet. Twenty decks and a height of 240 feet makes the ship taller than the Eiffel Tower.) The Queen Mary’s capacity was 2,140 passengers while the Icon OTS carries 7,600 passengers.

The Queen Mary was one of the largest ocean-going ships of its day. In fact, the River Clyde in Glasgow, Scotland where she was built had to be dredged to allow for the ship to be floated out. (Even with that, the ship ran aground in March 1936 while leaving the River Clyde.) As an aside, the ship was originally supposed to be named after the late Queen Victoria (in keeping with Cunard’s tradition of its ships’ names ending in “ia”). But when the Cunard chairman asked King George V for permission to name the new ship after Great Britain’s “greatest Queen,” the king replied that his wife, Queen Mary, would be delighted. True story.

The interior of the Queen Mary was very luxurious and decorated in Art Deco style. It had all the things you would expect including dog kennels, telephone connectivity to anywhere in the world, and air conditioning. It was the first ocean going vessel to be equipped with a Jewish prayer room. This was done purposely in response to the antisemitism of Hitler and Nazi Germany. Over the years, the Queen Mary was the only way to travel for celebrities such as Elizabeth Taylor, Abbott & Costello, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Laurel & Hardy, Cary Grant, and a six-time passenger, Winston Churchill. A large map in the main dining room tracked the ship’s position on the Atlantic using a crystal model of the ship. Both routes, north and south, were shown ⏤ the southern, or winter/spring route was used to avoid hitting icebergs. Yes, the Queen Mary had enough lifeboats for everyone on board. Cunard’s predecessor, White Star Lines, learned their lesson twenty-four years earlier.

World War II

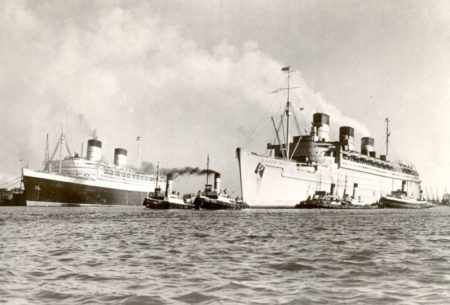

Leaving Southampton in late August 1939, the Queen Mary was escorted across the Atlantic by the British battlecruiser, HMS Hood. By the time she reached New York City (NYC), World War II had begun. The Queen Mary was ordered to stay in NYC until she received further orders. On 7 March 1940, Cunard’s new RMS Queen Elizabeth (named after King George VI’s wife; later known as the “Queen Mother”) arrived at Pier 90 while the inactive French ship, SS Normandie, was docked at Pier 88. For fourteen days in March, the world’s three largest ocean liners were docked side-by-side. On 21 March, the Queen Mary received her orders to sail for Sydney, Australia where she would be converted to a troop transport vessel.

While at the Cockatoo drydock, the ship was stripped of its wood (or covered in leather) and luxury furnishings and fittings including tapestries and paintings while six miles of carpet were removed, and 220 cases of fine china were put in storage. (I’ll bet they kept the cocktail bar for the officers.) During the conversion, the ship and its funnels were painted battleship grey. Combined with her speed, color, and secret travels, the Queen Mary was nicknamed, “The Grey Ghost.” The hull was fitted with protection from magnetic mines and thousands of triple-tiered, fixed wooden bunks and hammocks were installed throughout the ship. Although anti-aircraft guns were placed on the Sun Deck, it was really her speed that kept the Queen Mary safe from enemy U-boats. Reportedly, Hitler offered the Iron Cross and US$250,000 to any U-boat captain who sank either the Queen Mary or Queen Elizabeth.

Her first assignment as a troop transport ship was to carry soldiers from New Zealand and Australia to England. About 15,000 men could be carried in one crossing. The Queen Mary set the record in July 1943 when she carried 16,683 men on one trip. The ship was fast. It could do up to 38 knots and easily outrun the German U-boats which is why she often crossed the Atlantic without escort ships. One of her most famous passengers during the war was Winston Churchill. He crossed several times for meetings with other Allied leaders and traveled under the name “Colonel Warden.”

Demobilization

Demobilization officially ended on 30 June 1947. Only 1.6 million military personnel remained on active duty (reduced from 12.2 million two-years earlier). Active divisions were reduced from 89 to twelve. Operation Magic Carpet was considered a success with more than seven million people repatriated to America in only two years (at least the military brass branded it a success). It had been the largest mass people movement effort ever attempted.

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/crowded-ship-bringing-american-troops-1945/

The Queen Mary was retrofitted between September 1946 and July 1947 for her return to passenger service. She was retired in 1967 and the City of Long Beach, California purchased the ship. Today, the grand ship is moored in Long Beach and serves as a floating hotel, museum, event facility, and tourist attraction. The supernatural stories onboard the “Grey Ghost” are likely exaggerations. But you never know.

Next Blog: “Charles Marville and le Vieux Paris”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Frame, Chris. Queen Mary History. Chris’ Cunard Page. Click here to visit the web-site. Click here to read the article.

Goldwyn, Samuel (Producer) and William Wyler (Director). The Best Years of Our Lives. Samuel Goldwyn Productions, 1946. Click here to watch a scene from the movie.

National Library of Scotland. Restored color archive film of RMS Queen Mary on the Clyde (1936). Moving Image Archive. Click here to visit the web-site.

(this one’s for you Roland)

Niderost, Eric. RMS Queen Mary’s War Service: Voyages to Victory. Warfare History Network, 16 January 2017. Click here to read the article. (Note: this requires a subscription to read).

Sparrow, John C. History of Personnel Demobilization in the United States. Army Center of Military History. Washington, D.C.: CMH Publications, 1994.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I apologize to all of you who have contacted us in the recent weeks and months. We normally try to respond in a timely manner with comments or follow-up on any issues you raise. We have been delinquent in responding in our normal manner. Unfortunately, we’ve been dealing with aging parent issues, and it has taken an inordinate amount of our time. Please don’t stop communicating with us because of a lack of response. I have a pile of e-mails on my desk, and they will not be neglected. Hang in there with us. Your patience is greatly appreciated.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thanks to Jean-Paul Pallud for contacting us regarding our 2021 blog, OB West (click here to read the blog). He wanted us to know that five of the images I used in the blog were his photographs. I got the photos out of a magazine called After the Battle. I purchased several back issues because I was so impressed with the articles. The images were not credited, and I had an impossible time finding out who to credit. I even went as far as contacting the magazine but never heard back from them. (Unfortunately, according to Jean-Paul, the magazine no longer exists.)

Well, I’m happy Jean-Paul took the time to let us know. Sandy has corrected the image captions so future readers will know who took the photographs. I try very hard to make sure the image captions we use are correct and appropriate credit is given to the photographer and owner even when the image is the public domain. Mistakes happen and I’m grateful to those of you who contact us about errors and omissions. We immediately correct whatever is pointed out to us as the problem.

Jean-Paul is a rather prolific author of books on World War II and was a contributing writer to After the Battle. I’m looking forward to reading some of his books and maybe find an interesting topic to put into a blog. In the meantime, I’ve asked Jean-Paul to write a guest blog for us in the future. Stay tuned.

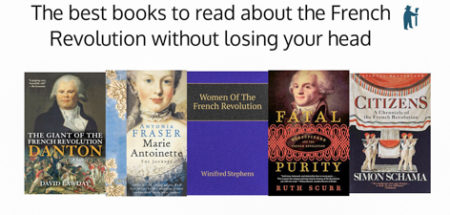

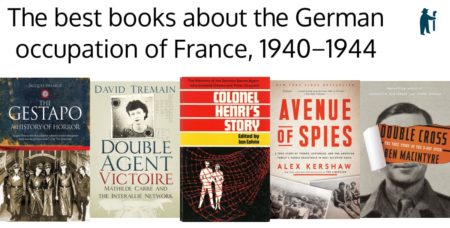

Shepherd.com is like wandering the aisles of your favorite bookstore.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Check out Stew’s new bookshelf on the French Revolution.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2024 Stew Ross