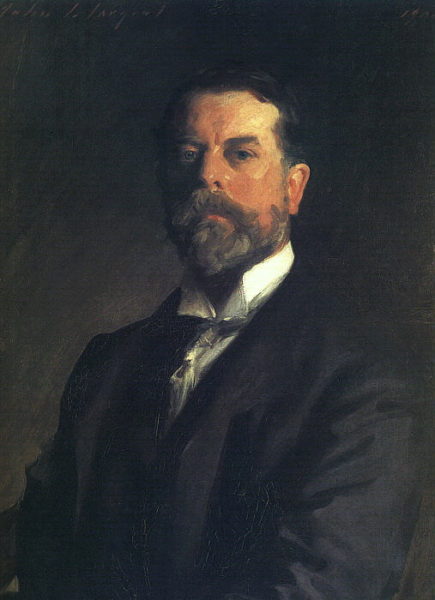

One of my favorite artists is John Singer Sargent (1856−1925). He was considered one of the leading portrait painters of his generation albeit as a “society artist” which some critics used in a derogatory manner towards him. Despite his American citizenship, Sargent lived abroad his entire life and became fluent in many languages, including speaking French without an accent. He trained under Carolus-Duran and passed the rigorous, one-month exam to gain admission to the prestigious art school in Paris, the École des Beaux-Arts. At the age of 21, Sargent’s paintings were first accepted into the Paris Salon and his career was launched as a portrait artist.

While this blog isn’t all about John Singer Sargent, his story intertwines tightly with the story of Virgnie Amélie Avegno Gautreau or Madame X as she infamously became known to Paris society. She would become Sargent’s most famous model and his most controversial. Her portrait created an immense scandal in Paris society and the art world in 1884. Whereas the scandal would engulf both the artist and the model, the artist’s reputation would eventually recover but the same could not be said for Madame X.

DID YOU KNOW?

Most of us know that adultery was an accepted behavior in France among the nobility (both sides were equally guilty) but as long as it was kept quiet, there would be no reason for alarm or at worst, a scandal. Marriages back then were arranged for political or economic reasons. Love never really played a part in the decision-making process (this probably was a major reason behind this behavior—not to mention boredom of the rich). There were definite periods of time when debauchery reached its zenith in French society (e.g., during the reign of King Louis XV and the Second Empire of Napoléon III). However, by 1871, the Third Republic was formed and henceforth, the nobility would be pushed aside in favor of the bourgeoisie (this is commonly known as the beginning of the Belle Époque period or perhaps maybe the French were beginning to reject the Victorian era morals and disciplines). Yet this concept of taking on a paramour did not subside as the status of nobility declined (it never really caught on too well with the working class or proletariat—husband and wife had to work for a living and they were typically equals in marriage and work). Society women would normally change wardrobes anywhere from four to five times a day depending on the event (e.g., lunch, afternoon tea, dinner, after dinner drinks, and midnight buffets). One event which forced women’s fashions to evolve was the “four-to-five.” This was considered the appropriate hour for infidelity. It was widely accepted the rendezvous would take place during this hour. Women were dressed in hoops, bustles, corsets, and petticoats making it difficult to arrange themselves quickly after their activities were finished. Some men would provide their lady friends with hairdressers and maids to assist them afterwards. One fashion change was the replacement of ribbons with hooks on the corsets. In the morning, the woman’s husband would tie her bows on the corset and then in the evening, he would notice the bows were tied differently. Hooks began to be used to disguise the evidence of her infidelity. Before too long, those testy garments were discarded in favor of loosely fitting gowns. As we say when looking for a fast food place or gas station on the interstate, “it has to be easy off, easy on.”

Let’s Meet Amélie

Virginie Amélie Avegno (1859−1915), born in New Orleans, was of noble French Creole descent. Her grandmother (Virginie Ternant) owned a rather large plantation—and its 147 slaves—called Ternant (later changed to Parlange) where Amélie would spend her summers (she never used Virginie as her first name). At the time, the Ternant family was likely the largest land owner in the New Orleans area. The family also maintained a residence in Paris located at 45, rue Luxembourg (the street name was later changed to Rue Cambon by Baron Haussmann). Read More Madame X and Her Strapless Gown