Here’s a story I ran across while researching one of the walks for our next book, Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? Roundups & Executions. It’s one of those long-lost facts about Paris that has slipped into the historical fogbank. I don’t know how many past or present French teachers read my blogs, but I think I will go out on a limb here. I’ll bet most French teachers aren’t aware of the major slum once located in the middle of historic Paris (2e) called la cour des miracles. If they could squeeze their students into Dr. Who’s time travelling space ship, dial back to 16th- or 17th-century Paris, and set course for a large area now bounded by four contemporary streets, the time travelers would find themselves in the middle of a dangerous community of thieves, beggars, prostitutes, and murderers. Before you leave, I would recommend you arrive during the day.

Did You Know?

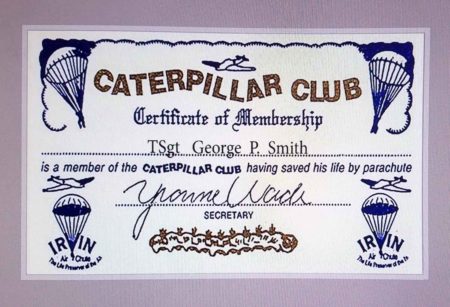

Did you know that there is an organization called the Caterpillar Club? No, it’s not a country club for the executives of Caterpillar, Inc. It’s an association of people who have successfully deployed a parachute to bail out of a disabled aircraft. The informal club is maintained by Airborne Systems (click here), a manufacturer of parachutes. If an applicant’s experience is authenticated, they are issued a certificate and silver pin. The nationality, ownership of aircraft, or other factors are immaterial⏤only the fact that the person’s life was saved by using a parachute is what matters. (Oh, one other factor does matter: the aircraft had to have been disabled naturally, including being shot down.)

The founder of the club in 1922, Leslie Irvin, named it after silk threads that were used to make the original parachutes. The silver pins are in the shape of the silkworm, or caterpillar. The club’s motto is “Life depends on a silken thread.” By the end of World War II, about 34,000 people were members. Some of the aviator members include Gen. Jimmy Doolittle, Charles Lindbergh, and John Glenn. The first female member was Irene McFarland in 1925.

Many thanks to Greg Smith for supplying the images of his father’s certificate, membership card, and silver pin. T/Sgt George P. Smith (1920−1983) was the left waist gunner on a B-17 shot down in May 1943 over France. (click here to read the blog Rendezvous with the Gestapo)

Paris Building Periods

During the late 12th- and early 13th-centuries, King Philippe II Auguste constructed the first city wall surrounding Paris (both right and left banks) for the purpose of repelling attacks on the city. As the city expanded, King Charles V built a new wall on the right bank in 1566. By 1670, Louis XIV declared the city safe enough from outside attacks that he ordered the demolition of the walls. With or without a wall, 17th-century Paris was still a medieval town and dangerous. The streets were narrow and dark, the city was very noisy and congested, it smelled, and walking the streets, especially at night, put you in harm’s way. The houses were primarily constructed of wood, multi-storied but small, and sewage was disposed of by throwing it out into the middle of the street. Streets didn’t have names and there were no maps, so it was easy to get lost⏤everyone pretty much stayed in their own neighborhoods. There were no sidewalks or curbs so being run over by horses pulling a carriage was a potential hazard. Another reason not to venture far from home was the fear of being assaulted, robbed, or murdered by roving criminals. Yet, attacks by feral animals (e.g., wild boars) that roamed the streets were responsible for a majority of deaths. Read More Cour des Miracles