My most recent AARP magazine (October/November 2018) featured an article on Martha Hall Kelly, the author of Lilac Girls. Ms. Kelly’s mother passed away in early 2000 so, at the urging of her husband, Ms. Kelly took a therapeutic trip to the Bellamy-Ferriday House & Garden in Bethlehem, Connecticut to see its famous lilac gardens.

While taking the house tour, Ms. Kelly noticed a group of women in a photograph sitting on Caroline Ferriday’s desk. One of the guides watched Ms. Kelly’s fascination with the photo and told her, “Those are the rabbits. Prisoners at Ravensbrück, the largest all-female concentration camp in Hitler’s Third Reich.”

Ms. Kelly admitted she never had any interest in history. That is, until she saw a photograph of the Rabbits and learned of their horrifying stories.

Did You Know?

Did you know the Bellamy-Ferriday House & Garden located in Bethlehem was bequeathed by Caroline Ferriday to Connecticut Landmarks on 27 April 1990, the day Ms. Ferriday passed away? Learn more about the Bellamy-Ferriday House & Garden here.

The house was built in 1754 (with a second building phase in 1767) by Rev. Joseph Bellamy (1719−1790). The family held it until 1868 when several other owners took possession. Finally, in 1912, Henry and Eliza Ferriday purchased the house and its 100-acres. The Ferriday family would spend their summers there (unfortunately, Mr. Ferriday died two years after the purchase) and upon Eliza’s death, their only child, Caroline, inherited the property. She continued to upgrade the house and live there during the summers throughout her life (winters were spent in New York City). The estate is famous not only for the 18th-century house but for the beautiful gardens which Miss Ferriday’s mother began and Caroline expanded. The gardens are known for Caroline’s favorite flower: lilacs.

KZ Ravensbrück

Ravensbrück concentration camp was created in the autumn of 1938 with its first prisoners delivered on 18 May 1939. The camp was built specifically for women and located next to the small town of Fürstenberg, fifty miles north of Berlin. It was also near the hideaway where Heinrich Himmler stashed his mistress. The initial group of prisoners were primarily Polish but soon, women who were Jewish, gypsies, German, and political or resistance members were incarcerated. Female foreign agents (under the Night and Fog program-read the blog here) were sent to Ravensbrück, often to be executed. Eventually, babies and children became part of the camp’s population. During its existence, more than 130,000 people went through Ravensbrück with approximately 90,000 dying from execution, starvation, illness, or being worked to death.

The camp was expanded many times due to the heavy influx of prisoners during the six years of its existence. Although it had a crematorium, it wasn’t until November 1944 that a gas chamber was constructed. Himmler decided the inmates (including the children) needed to be eliminated more efficiently in order to make room for additional prisoners.

Ravensbrück was eventually liberated by the Soviets (in the process, many of the prisoners were raped) and its location fell into the Soviet zone of occupation after the war. It was also one of the last camps liberated thus giving the Nazis plenty of time to destroy documents implicating their crimes. The result was that the atrocities committed in Ravensbrück would not be known for many decades. However, the camp’s infamous medical experiments were front and center beginning with the Nuremberg trials and as we’ll see, the actions of Caroline Ferriday ten years later.

Caroline Ferriday

Caroline Ferriday (1902−1990) was a life-long Francophile, activist, and philanthropist. During the war, she supported the French Resistance as a founding member of the “France Forever, the Fighting French Committee in America.” After the war, Caroline belonged to the “National Association of Deportees and Internees of the Resistance” (ADIR), an organization founded by women members of the French Resistance who survived the Nazi concentration camps. As a result of her involvement, Caroline met many resistance survivors including Genevieve de Gaulle (General de Gaulle’s niece), Germaine Tillon, and Jacqueline Péry d’Alincourt. It was through her interaction with Ravensbrück survivors that Caroline learned about the 84 young and healthy women picked by the Nazis doctors at Ravensbrück for medical experiments. These women were known by the inmates as the Lapins or, Rabbits because they were used for these hideous lab experiments.

The Doctors

The head doctor at Ravensbrück was Karl Gebhardt (1897−1948). Dr. Gebhardt also served as Himmler’s personal physician. He was sent to Poland by Himmler in June 1942 to save the life of Reinhard Heydrich (Himmler’s second-in-command of the SS and Gestapo) after an assassination attempt by several Polish resistance members. Heydrich survived the attack but died days later from an infection. Gebhardt refused to treat Heydrich with sulfa drugs (as suggested to him by Hitler’s doctor) and his patient died. Hitler and Himmler were not pleased. As the mastermind behind the Ravensbrück medical experiments, Gebhardt made sure that the results of the sulfanilamide drug experiments on the women were skewed in his favor to prove to the Führer and Himmler that the sulfa drugs would not have saved Heydrich’s life.

One of his Ravensbrück assistants, the only woman doctor in the camp, Herta Oberheuser (1911−1978), focused on finding treatments for battle wounds. She would cut open the legs of the medical “volunteers” and introduce foreign objects such as wood, rusty nails, glass slivers, dirt, or just about anything a soldier might encounter during combat. Then the victim would be treated with various drugs to see which drug produced the best results. Oberheuser was also responsible for killing children and babies for the purpose of dissecting them.

The Experiments

The Ravensbrück experiments were designed for two purposes. First, the doctors wanted to find the best drugs to treat soldiers after being wounded. So, the victims were intentionally maimed and crippled before being treated with various drugs. Legs were opened, muscles removed, bones broken or shattered with infectious germs introduced into the wounds. The second type of operation was “for which the world does not yet have a name.” For example, Gebhardt conducted experiments whereby limbs were amputated in abnormal places and the victim was killed on the operating table at the end of the procedure.

The Rabbits

Of the 84 women chosen for the experiments, seventy-four were Polish. Five of the Polish women died immediately from their infections; six were executed after surgery (usually with lethal injections); and sixty-three miraculously survived (albeit with life-long disabilities including being crippled and in chronic pain).

In February 1943, the women drew up a letter protesting their treatment and gave it to the camp’s commandant. Some of them were able to get their messages to the outside world. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICC) was informed of the atrocities but refused to take any action—the head of the ICC was a personal friend of Gebhardt.

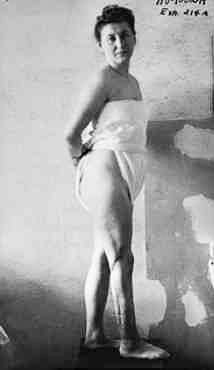

As the Soviets were closing in on the camp in the waning days of the war, the SS was instructed not to leave any evidence of the medical experiments. This meant the survivors were targeted for execution. The Rabbits were protected by the other prisoners and ultimately survived what would have been sure death. They also knew that evidence in any post-war trials would be needed. The women smuggled a camera into the camp and took pictures of their legs and other body parts used in the experiments.

In late April 1945, 7,500 Ravensbrück prisoners were released as part of the “White Buses” project (a future blog). The Rabbits were not released but they managed to entrust the camera film to Germaine Tillion who had it developed in Paris. The images would later be used by the Allies to prosecute the doctors.

Post-War

Four of the Rabbits testified at the Nuremberg trial called “The Doctors’ Trial.” Gebardt was found guilty and hanged. Oberheuser was sentenced to twenty years but served only four (pardons and commuted prison sentences were common for convicted Nazi war criminals). Released in 1952, Oberheuser became a prosperous doctor in West Germany until a former Ravensbrück prisoner recognized her and Oberheuser’s medical license was revoked. Caroline Ferriday was instrumental in the process to revoke Oberheuser’s license.

The story of the Rabbits was revealed to Caroline in the 1950s. By 1958, she had alerted America to the horrors of Ravensbrück and in particular, the medical experiments. Caroline started by enlisting the help of Norman Cousins, editor of the Saturday Review and Benjamin Ferencz, one of the former Nuremberg Trial prosecutors. She arranged to have thirty-five of the surviving fifty-three Rabbits come to America to receive medical treatment. The Rabbits were now known as “The Ladies” and they stayed in small groups with host families around the country. Cross-country publicity trips highlighted their stories and at the peak of their visit, the U.S. Congress hosted them at a special luncheon in the Senate dining room. The German government, originally denying any responsibility, agreed to pay the medical costs for thirty of the Ladies and to explore further compensation.

Caroline remained close friends with the Ladies up until her death in 1990. On her desk at the Bellamy-Ferriday House is an autographed photo of Charles de Gaulle and a commemoration certificate from the French government. Next to the desk is her typewriter—a memory of all those letters she wrote to gain the public and private support for the Rabbits.

Recommended Reading and Viewing

Helm, Sarah. Ravensbrück: Life and Death in Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women. New York: Anchor Books, 2015.

Kelly, Martha Hall. Lilac Girls. New York: Valentine Books, 2016.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

We are days away from Christmas. Sandy and I would like to wish everyone a Merry Christmas. We also hope that all of our Jewish friends had a wonderful Hanukkah! Whatever you do or wherever you go, please stay safe.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thank you to Charles P. for contacting us in regard to the Sussex Plan. Charles is the president of the OSS Society (www.osssociety.org) and was looking for a contact to obtain a particular image of the Sussex Plan (click here to read the blog). I’m confident my friend, Dominque Soulier can accommodate Charles’s request.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs. Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2018 Stew Ross