What’s in a last name? Everything. A last name can have consequences: positive or negative. In Albert’s case, it was both.

I’ll bet 99.9 percent of you didn’t know Hermann Göring had a brother let alone one who was a fervent anti-Nazi credited with saving hundreds of Jews and other Untermensch (sub-humans) during the twelve years of Nazi rule.

Well he did. Unfortunately, his last name has been etched in the infamy of the 1930s and 1940s world events which kept him from receiving the recognition and honors afforded others who took the same type of risks during World War II.

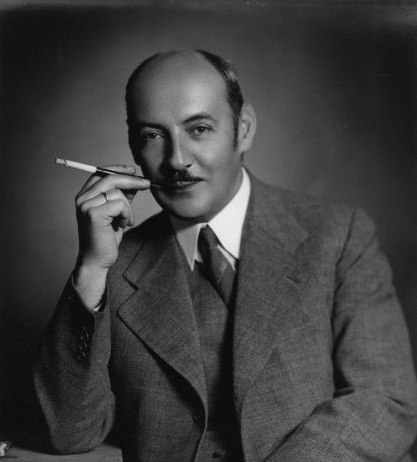

Let’s Meet Albert Göring

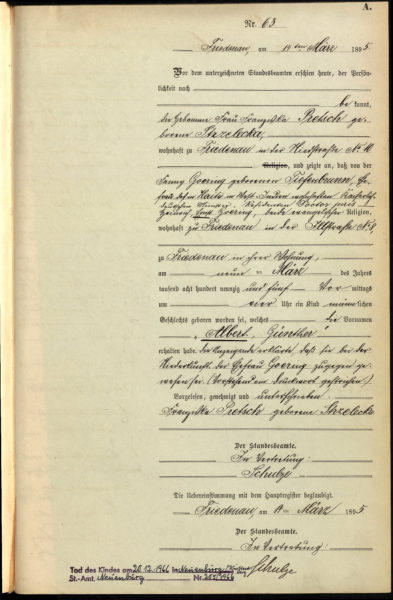

Albert Göring (1895−1966) was the fifth child of a German bureaucrat (Heinrich) and his second wife (Franziska), a Bavarian peasant. Heinrich was frequently absent and the family lived with the Göring children’s godfather, Dr. Ritter Hermann von Epenstein. He was a wealthy real estate investor and the Göring family would migrate every year between Epenstein’s castle in Mauterndorf (during the summers) and his primary residence, the Veldenstein castle. Dr. Epenstein was Catholic but his heritage was Jewish (his father had converted in order to marry).

Albert’s mother began an affair with Epenstein in early 1894 and there has been some speculation that Albert was born from this illegitimate relationship. This was never proven but Albert’s personality, appearance, and cavalier attitude were similar to his godfather. If true, Albert would have been half-Jewish under the Nazi Nuremberg Laws.

Hermann, the older brother, was heavyset, athletic, and enjoyed being the center of attention. Albert exhibited none of these traits. However, Albert—unlike his brother—had very high morals, ethics, and a sense of justice. He once saw a group of Jewish women scrubbing the street and joined them. After his papers were inspected by the SS officer in charge and it was determined he was the Reichsfeldmarshal’s brother, the scrubbing ceased. A similar incident occurred shortly after the Anschluss of Austria. A seventy-five-year-old Jewish woman was being harassed by a group of Nazi thugs who had hung a sign on her reading “I am a Jewish sow.” Albert came upon this unfortunate scene and burst through the crowd to rescue the woman. The Nazis turned on him and Albert began to fight them. He was immediately arrested by the Gestapo and interrogated. Upon learning his identity, Albert was released after his first arrest with the admonishment to never let this happen again. He didn’t follow their instructions and would be arrested four more times during the war by the Gestapo for his “defeatism,” “anti-National Socialism,” and being “politically dangerous” (he was never arrested for assisting Jews or others).

In defiance of the Nazis taking over his country, Albert moved to Vienna and applied for Austrian citizenship. After the Anschluss, he moved to a Nazi-free Romania living in Bucharest. Unfortunately, by early 1941, the anti-Nazi Romanian king had been removed and replaced by General Ion Antonescu. Romania became an Axis country and soon its Jewish citizens and others were being deported to concentration camps. Once again, Albert found he couldn’t get away from the Nazis.

The Gestapo

By 1939, Albert Göring and his views on Hitler and Nazism were already known to the Gestapo and they dubbed him a “public gangster.” After his first arrest in 1938 by the Gestapo, Heinrich Himmler kept close tabs on him. Although Hermann Göring founded the Gestapo in 1933, it was turned over to Himmler and his Schutzstaffel (SS) the following year. This began a strained relationship between Göring and Himmler with each trying to protect their respective positions and status with Hitler. Himmler would have done anything to discredit Göring and Albert Göring was the perfect foil to accomplish that goal.

Despite his bluntness and being so public with his opinions on Hitler, his brother, and the Nazi regime, Albert was rather clandestine in his efforts to save lives, gain people’s freedom from the concentration camps, or provide financial assistance to the resistance movements and Jewish organizations.

By August 1944 and living in Bucharest, Albert felt the Gestapo heat turned up a couple of notches. It got back to Manfred von Killinger, German consul to Romania, that Albert was publically calling him a killer (which was true). Killinger, through SS Obergruppenführer Karl Hermann Frank, got Himmler to not only issue an arrest warrant for Albert but also an order to assassinate him. Albert Göring was clearly beginning to lose his special privileges as Hermann’s brother. He had to escape from Bucharest.

Albert was eventually brought to Berlin by his brother. Hermann got him off the hook but was very clear this was the last time he would help Albert. Based on accusations made by his secretary (a Gestapo agent), Albert was arrested again in October 1944. Hermann forgot his earlier warning to Albert and although difficult, he got his brother released once more (and the last time) from the clutches of the Gestapo and Himmler. He told Albert to go back to his family and wait. Albert took his brother’s advice and returned to Austria and waited out the collapse of the Third Reich in Salzburg.

The List of Thirty-Four

On 9 May 1945, Albert surrendered to the Americans in Salzburg. Four days later, he was formally arrested and transported to the 7th Army Interrogation Center (SAIC) in the Bavarian town of Augsburg (four years earlier, Rudolf Hess took off from the Augsburg airport on his secret flight to Scotland). At SAIC, Albert would be reunited with his brother for the last time.

Albert Göring knew the real reason for being arrested: his last name. He began to compile a list of thirty-four names with the stories of how he had saved their lives from certain death at the hands of the Nazis. He thought the Allies would investigate and clear him. Unfortunately, his interrogators had already made up their minds: Albert Göring was guilty because of his last name and no list would convince them otherwise.

By mid-September 1945, Albert was transferred to Nuremberg where the interrogations continued and his health deteriorated. In June 1946, Albert had been transferred to yet another internment camp where the skepticism of his stories continued. He was to remain there until serendipity played its hand.

Major Victor Parker was assigned to interrogate Albert. During the interrogations, Albert went through the list once again. He told the story of how he had saved Frau Franz Lehár (number 15 on the List of Thirty-Four). Franz Lehár was one of Germany’s master composers and a favorite of Hitler. He married Sofie Paschkis, a Jewish woman. One day, the Gestapo came to pick up Frau Lehár for deportation. One phone call led to another which led to another. The last call was to Albert in Bucharest and Frau Lehár was released. Major Parker was stunned! His christened name was Paschkis. Frau Lehár was Major Parker’s aunt.

Eventually, many of the thirty-four testified on behalf of Albert. He was scheduled to be released when the government of Czechoslovakia demanded his extradition. Again, he went through interrogation and finally a trial. Witnesses appeared to testify as to his actions in saving lives and providing financial support for the victims of Nazism. The Gestapo case file detailing their displeasure with him was the last piece of evidence. The verdict was not guilty and Albert was finally given his freedom on 14 March 1947, five months after his brother gained his freedom by biting down on a fatal cyanide capsule.

Later Life

Albert returned to Austria penniless and found he couldn’t obtain a job because of his last name. Despite the family urging him to change his last name, Albert refused. He fell into disrepair and his third wife, a former Czech beauty pageant winner, divorced him. Mila and their daughter, Elizabeth, moved to Peru—Albert never saw them again.

Albert finally found employment and moved to Munich where he and his fourth wife lived in very meager surroundings. He was offered lucrative business opportunities but turned them down. He would always quote the German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer, when asked why he didn’t take advantage of being able to live better: “In this world nothing becomes lost; it just passes from one to another.”

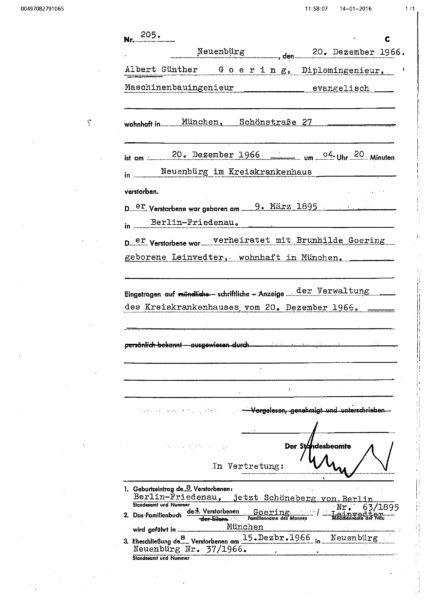

Albert Göring died of pancreatic cancer on 20 December 1966. He was buried in the Göring plot in Munich’s Waldfriedhof cemetery. The grave was leveled in 2008 and no longer exists.

Recommended Reading

Burke, William Hastings. Thirty Four: The Key to Göring’s Last Secret. London: Wolfgeist Limited, 2009.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

We have a lot of traveling planned for this year but no research trips. When not traveling, we’ll be hunkered down in our library writing the next two books – Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2018 Stew Ross