I grew up in the Netherlands during the 1960s when Queen Juliana was the reigning monarch of The Kingdom of the Netherlands. (Commonly referred to in English as “The Netherlands,” or “Holland.”) She was the daughter of the former queen, Wilhelmina, who abdicated in 1948 for health reasons. I can vaguely remember my parents and others talking about the former queen and some of her perceived eccentricities. Other than that slight exposure to her, I have only followed the Dutch royal family since Queen Juliana and her daughter, Beatrix.

Fast forward to 2020 when I got my hands on Robert Matzen’s book, Dutch Girl (see below in the recommended reading section). I really enjoyed his book on Jimmy Stewart (Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe) so I thought I’d take a chance on reading about one of my favorite actors, Audrey Hepburn. One of the things I learned was the role Queen Wilhelmina played during World War II and how much Hitler hated her and the royal family. He despised them so much that orders were given to round up anyone who were friends, cronies, or political friends of Wilhelmina and her family and hold them as hostages for possible execution in retaliation for attacks on German soldiers. This is where Audrey Hepburn comes into our story. Oh, I also learned the one secret Audrey tried to hide for her entire life.

Did You Know?

Did you know that on 12 July 1973 a disastrous fire occurred at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in Overland, Missouri? The fire destroyed between sixteen to eighteen million official military personnel files. The U.S. Army (including the United States Army Air Forces, or USAAF) and United States Air Force files were affected and the estimated loss for each was 80% and 75%, respectively. Army files for men and women discharged between 1912 and 1960 were lost while destroyed Air Force files affected those discharged between 1947 and 1964. No duplicate files were ever maintained, nor were microfiche copies produced. In fact, there were no name indexes created prior to the fire. In other words, a complete listing of the lost records is not available. Perhaps this is the reason why I cannot locate any service records on my uncle who was a P-47 Thunderbolt fighter pilot (97 missions) during World War II.

The House of Orange-Nassau

The Netherlands has a long history dating back to prehistoric time with Neanderthals occupying sites near Maastricht. The scope of the country’s history is far too complicated for this short blog, so I’ll fast forward and pick up the story in the 17th-century, commonly considered the “Dutch Golden Age.” Seven provinces had declared their independence and formed a confederation with the government located in The Hague. In 1795, the Republic of Seven United Netherlands was conquered by French troops and in 1806, Napoléon appointed his brother, Louis Bonaparte, as king. At that point, the country became a kingdom and remained so after Napoléon’s defeat.

One of the provinces consisted of two areas separately known as Noord-Holland and Zuid-Holland (i.e., North Holland and South Holland). These two areas provided the largest contribution to the nation’s economy and wealth so, the term “Holland” became a commonly used name to identify the entire country. (Today, there are twelve provinces.)

The roots of the Dutch monarchy date to 1403 when a Breda noblewoman, Johanna van Polanen (1392−1445) wed a German count, Engelbrecht I of Nassau-Dillenburg (c. 1370−1442). Skip forward a hundred years when René of Chalon (1519−1544) inherited the principality of Orange in France. While René became the first prince of Orange-Nassau, it was his cousin, William the Silent, or William I (1533−1584) who founded the House of Orange-Nassau.

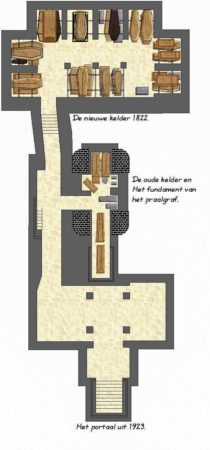

William of Orange moved to the Prinsenhof in Delft in 1572. (The Prinsenhof is a medieval urban palace where the princes once resided.) From there, he led the successful revolt against Spain and in 1579, the Union of Utrecht was signed thus laying the foundation for the modern-day country. Unfortunately, William was assassinated in 1584 inside the Prinsenhof (where you can see the bullet holes in the wall) and he was buried in the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft. (Inside the 14th-century church is the royal burial chamber but it is closed to the public.)

After Napoléon was defeated in 1813, Prince William (1772−1843; son of William V, Prince of Orange of the Dutch Republic) returned from exile in England and named himself, “Sovereign Prince of the Netherlands.” However, after Napoléon escaped from Elba in 1815, Prince William proclaimed the Netherlands to be a kingdom and he was crowned William I, king of the new “Kingdom of Orange-Nassau.” He abdicated in 1840 and his son, William II (1792−1849), became king. Unlike England, many of the Dutch monarchs abdicated the throne in favor of their offspring.

Queen Wilhelmina

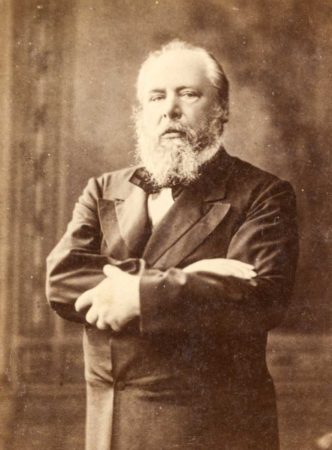

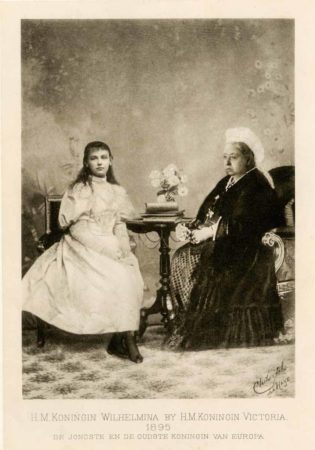

So, now we finally get to Queen Wilhelmina (1880−1962). She was the only child of King William III (1817−1890) who was sixty-three when his daughter was born. Her grandfather and great-grandfather were William II and William I, respectively. Wilhelmina’s mother was the immensely popular Princess Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont (1858−1934).

After Wilhelmina’s father died, her mother became regent for the ten-year-old queen. The Netherlands had adopted a “semi-Salic” system for inheriting the throne. In other words, males were favored but if no male relatives were available, then a female could be placed on the Dutch throne. (French Salic law excluded females from the line of succession.) All eligible males died before 1890 and so, the king made the decision to name his daughter as his successor. I suppose the oft used expression, “Last man up” had to be changed.

Wilhelmina was crowned queen on 6 September 1898. She reigned over the Netherlands for almost fifty-eight years before abdicating in favor of her daughter, Juliana. (Who, by the way, abdicated the throne in 1980 for her daughter, Beatrix and who in turn, abdicated in 2013 in favor of her son, Willem-Alexander.) During her reign, Wilhelmina dealt with national economic crises as well as international conflicts such as the Boer War, World War I, and World War II.

Click here to watch the video Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands Abdicates Her Throne (1948).

Queen Wilhelmina married Duke Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in February 1901. The marriage was not a happy one for Wilhelmina as her husband was not faithful and she came to accept the marriage for what it had become: a vehicle for producing an heir to the throne. (The Dutch feared that without an heir, the country would come under the thumb of Germany.) Unfortunately, she suffered numerous miscarriages but finally, eight years into the marriage, Princess Juliana (1909−2004) was born and the Dutch throne had its heir.

Wilhelmina was extremely popular with her Dutch subjects. The queen was stubborn, outspoken, and never one to mince words. She did not like politicians and always stood up for what she considered to be best for Dutch citizens. The queen strongly supported the Boers in their fight against the British between 1899 and 1902. She was responsible for keeping the Netherlands neutral during World War I but despite being neutral, Wilhelmina was always concerned about a possible German invasion. She told the German Emperor, Wilhelm II, that she would open the dikes on his invasion force and drown them. (I’m sure she was kidding . . . not.) After the war, the German Kaiser Wilhelm fled to the Netherlands where Wilhelmina refused to turn him over to the victorious Allies (the two leaders were distant cousins) who undoubtedly would have executed him. About the same time, the country was caught up in civil disturbances due to the Russian Revolution and Bolshevik movement. She squashed the revolts through her support and popularity with the people of Holland.

It is her role as an exiled monarch during World War II that brought her closest to her subjects and for what she is remembered today . . . a symbol of Dutch resistance.

The German Invasion

On 10 May 1940, the German army invaded the Netherlands with the Dutch army surrendering on 14 May, after Rotterdam endured four days of carpet bombing by the Luftwaffe’s heavy bombers. The city center was destroyed and rebuilt after the war. Although Queen Wilhelmina was anti-British, she and her family boarded the HMS Hereward and fled the Netherlands. The British destroyer was sent by King George VI to bring the royal family to London. (Princess Juliana and her children ultimately were sent to Canada.)

Click here to watch Queen Wilhelmina in Holland during WWII.

In London, the queen established and took over a Dutch government-in-exile and she would not return to her country until areas of the southern Netherlands were liberated in March 1945. Each year, Holland celebrates its liberation on 5 May of (click here to read the blog, Twenty Years After the End of World War II: Childhood Memories). Wilhelmina and the government used the Secretariat Office as their administrative offices at 77, Chester Square in London. Unfortunately, she and her prime minister, Dirk Jan de Geer, did not get along. There was no parliament and never enough support staff. The situation created quite a bit of tension between the queen and the prime minister but eventually, with the assistance of others, Wilhelmina removed de Geer from power.

Click here to watch Netherlands during WW2 1940-45.

The Archenemy of Mankind

One thing Wilhelmina shared with Winston Churchill was an intense hatred of Adolph Hitler. She referred to him as “The Archenemy of Mankind” and her official portrait became a symbol of Dutch resistance. Prior to the war, Hitler respected the Dutch for what he considered their “Aryan roots.” The Nazis believed the Dutch bore the closest resemblance to their image of a perfect Aryan and as such, did not consider the country and its citizens with the same degree of contempt as other occupied countries. This was the primary reason why Hitler released all Dutch military prisoners after the invasion and Dutch surrender.

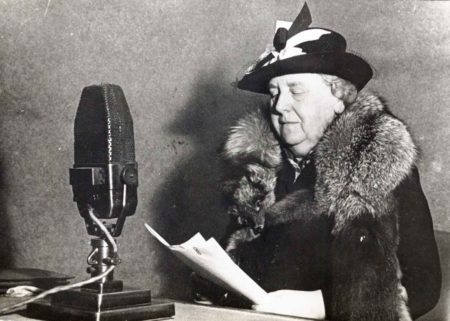

Hitler’s attitude toward the Dutch and in particular, Queen Wilhelmina, changed almost immediately after she began transmitting daily messages to her subjects beginning 28 July 1940 over BBC Radio Oranje. In her typical bluntness, Wilhelmina made no bones in her radio messages about how she felt toward the Führer, the Nazis, and Germans in general. During her broadcasts over Radio Oranje, Wilhelmina never referred to them as “Germans.” She used the term Moffen, or Moff. It was a Dutch ethnic slur meaning someone who was unwashed and backward.

Click here to watch the video Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands Broadcasts in Britain (1940).

Hitler responded by outlawing any celebrations of the queen’s birthday. However, Hitler’s deadliest personal attack on the exiled queen and her family came when he ordered Reichskommissariat Niederlande, Arthur Seyss-Inquart (1892−1946) to roundup and hold as hostages any person related to, friends of, or connected to the queen, the House of Orange, or the royal family.

Uncle Otto

So, how is Audrey Hepburn connected to the story of today’s blog?

Her favorite uncle and father figure, Count Otto van Limburg-Stirum (1893−1942) was the husband of Audrey’s mother’s sister. The Limburg-Stirum family traced its roots back to the 11th-century and was connected to the House of Orange since its founding. Many of the Limburg-Stirum family, at one time or another, worked for the queen or the Dutch royal family and Hitler knew this.

Otto was an assistant prosecutor and by February 1941, he was forced to prosecute people who broke Nazi laws such as listening to the BBC on the radio or singing patriotic songs. In November 1941, Otto was ordered to “name names” of Third Reich opposition leaders. After refusing, he was dismissed from the judicial system. This act of defiance along with his family’s close ties to Wilhelmina earned him a spot on the Nazis’ “enemy list.”

On 4 May 1942 (Audrey’s thirteenth birthday), two Dutch SS policemen arrested Otto at his home. He was one of 460 Dutch men rounded up and taken as hostages. They were not arrested because of their religion (i.e., Jewish). These men were arrested for being intellectuals, politicians, bankers, lawyers, educators, or anyone the Nazis viewed as a threat.

Three months later, the Dutch resistance carried out a minor act of sabotage. The Dutch were given until midnight of 14 August to turn over the people responsible for the sabotage. It was announced that if no one was identified by the deadline, hostages would be shot in retaliation. Nobody came forward.

At one o’clock in the morning on 15 August, Otto and four other men were taken out of prison, put in a truck, and driven to a secluded forested area half-way between Breda and Eindhoven. Once they arrived, the men were given picks and shovels and told to dig their graves. Upon completion, five wooden poles were produced, stuck in the ground, and the men were tied to the posts, blindfolded, and shot by a German firing squad. Each man was buried in a freshly dug pit with the execution poles thrown on top of their remains. Today, the site is a memorial to the five men and each grave is identified.

Otto was specifically chosen to be executed because of his relationship with Queen Wilhelmina. The Dutch Nazi Party (NSB) and Seyss-Inquart thought killing Otto would “teach the irritating old woman it was wiser to keep her mouth shut.”

Audrey’s Little Secret

Ella, Baroness van Heemstra (1900−1984) was Audrey’s mother and during the mid-1930s, Ella hung out with the pro-Nazi Mitford sisters who undoubtedly influenced Ella’s opinion of Hitler and the Nazi party. (Click here to read the blog, British Fascists and a Mitford.) It was a well-known fact that Ella supported Germany and a rumor had it that Queen Wilhelmina suggested to Ella’s husband that he divorce her so as to distance himself from her political beliefs. It was only after Otto’s execution that Ella turned her back on the Nazis and became an anti-Fascist and joined the Dutch Resistance.

Audrey Hepburn was embarrassed by her mother’s earlier support and association with the Nazis and successfully hid this part of her past as she worried that her acting career would be over if the truth came out.

The Belgian Predicament and Intervention

One last story about Queen Wilhelmina before we sign off. The king of Belgium, Leopold III (1901−1983), did not flee his country when it was invaded on the same day the Germans marched into the Netherlands. He and his family were held under house arrest by the Germans until their deportation to Austria in 1944. By early 1945, everyone (including the Germans) knew the war was close to an end and Hitler would be defeated. Leopold’s mother was concerned that her son and family would be executed by their captors (and rightfully so), and she contacted Wilhelmina for help.

Knowing the senior Nazi leaders were looking for ways to escape, Wilhelmina suggested trading Nazi escape lines for the safety of the Belgian royal family. Now remember, the members of the European royal families at that time were all related so it was very easy for them to communicate with one another. Wilhelmina’s idea of intervention made it to King George VI (Wilhelmina’s cousin), but it was declined because the Allies refused to strike individual deals as it would violate their steadfast policy of unconditional surrender. In the end, an intervention wasn’t necessary. King Leopold and his family survived.

Aftermath of the Occupation

The Netherlands had the highest per capita death rate of Nazi-occupied countries. More than two hundred thousand men, women, and children lost their lives during the occupation. More than half of these deaths were Jewish citizens who perished in the concentration and extermination camps. About seventy-five percent of the Dutch Jewish population were murdered by the Nazis.

Toward the end of September 1944, Seyss-Inquart ordered the complete blockade of the country in retaliation for a general rail-strike called for by Wilhelmina’s government-in-exile. No food was allowed into the country and between eighteen and twenty-two thousand people (many were elderly men and children) subsequently died from hunger during the winter of 1944 and 1945. Formally known as the Dutch Famine of 1944−1945, it is commonly known as Hongerwinter, or “Hunger Winter.”

Next Blog: “The Beautiful Enigma”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Bloks, Moniek. Queen Wilhelmina: A Collection of Articles. Self-published: Amazon KDP, 2020. Click here to visit the web-site.

H.R.H. Wilhelmina. Lonely But Not Alone. New York: McGraw Hill, 1960.

Matzen, Robert. Dutch Girl: Audrey Hepburn and World War II. Pittsburgh: GoodKnight Books, 2018.

Matzen, Robert. Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe. Pittsburgh: GoodKnight Books, 2019.

Riemens, Michael. “Majesteit, U kent het verkelijke leven niet”: De oorlogsdagboeken van minister van Buitenlandse Zaken mr. EN. Van Kleffens. Nijmegen, NL: Vantilt Uitgeverij, 2019. Dutch version. (English title: “Your Majesty, You don’t know the ugly life”: The War Diaries of Minister of Foreign Affairs mr. EN. Van Cleffens).

Schama, Simon. Patriots & Liberators: Revolution in the Netherlands 1780−1813. New York: Knopf Publishing, 1977.

State, Paul F. A Brief History of the Netherlands. New York: Infobase, 2008.

Zee, Henri A. van der. The Hunger Winter: Occupied Holland 1944-1945. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998.

BBC. Dutch WW2 Queen “considered Nazi swap for Belgian royals” 30 April 2019.

NL Netherlands. Holland’s occupation during WWII.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are on holiday this week. Looking at our travel calendar, I was able to write this blog ahead of time and have Sandy post it. Our blog today continues a ten-year string of unbroken published bi-weekly blogs. Hope you enjoy it!

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank (once again) Fabrice D. for being so gracious to share with me his list of addresses associated with key events surrounding the betrayal of the SOE Prosper circuit in mid-1943. While familiar with the Prosper circuit and its demise, I really had not dug very deep. Now that Fabrice has me scratching the surface, I am about to begin another journey that will add value to volumes two and three of our future books, Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please contact Stew directly for purchase of books, Kindle available on Amazon. Stew.ross@Yooperpublications.com or Contact Stew on the Home Page.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross