For those of you who have read my books, you know the featured walks and stories are heavily dependent on images. The same goes for our bi-weekly blogs. So, over the years I have become quite familiar with and adept at using various sources to locate images.

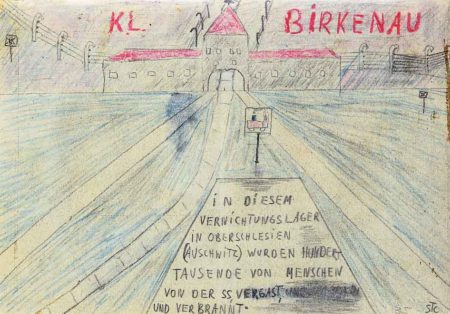

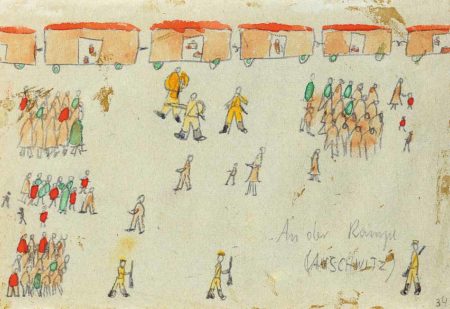

I found there are only two options available to obtain images of Nazi concentration camps during the war. The first are the photos taken by the Germans who worked in the camps. These are relatively scarce as the Nazi leaders did not want any archival evidence of the atrocities they were committing. The second option are the inmate drawings and paintings done either while a prisoner or from a survivor’s memory.

As the Allied troops liberated the camps, Gen. Eisenhower ordered his photographic units to take pictures. One of his motivations was to ensure people could never deny these horrific events had taken place. Many of us are familiar with the photos of emaciated prisoners, stacks of bodies, and ovens that were still warm. These images can be found in the German Archives (Bundesarchiv), various Holocaust memorial museum archives, and government archives such as the Imperial War Museum, Smithsonian Museum, and the US National Archives.

Today’s blog will focus on the illustrations made by camp prisoners and survivors. Click here to watch Paintings from Terazín Concentration Camp.

Did You Know?

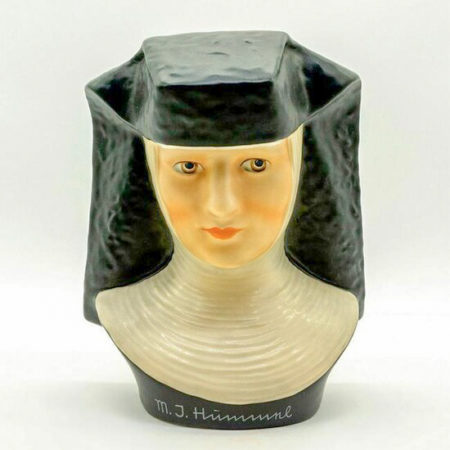

Did you know that the Hummel figurines your parents and grandparents collected are named after Sister Maria Innocentia Hummel? Berta Hummel (1909−1946), a devout Catholic, joined the Congregation of the Franciscan Sisters of Sießen in Bad Saulgau, Germany in 1931. She became known for her artwork which became the basis for the figurines.

The convent began to market Berta’s artwork to raise funds. Franz Goebel, a porcelain company owner, saw her work and convinced the convent to grant him sole rights to make figurines based on Berta’s art (she focused on paintings of children). Hitler learned of her work and attacked her depiction of the children (reportedly, they didn’t meet his Aryan standards). Berta’s work was banned in Germany, but she continued to produce drawings with the Star of David and other religious icons the Nazi leaders shunned.

By 1940, the Nazi government shut down all religious orders and schools. Berta was allowed to stay in her religious community, but the conditions were horrible. She contracted tuberculosis in 1944 and in November 1946, Sister Maria Innocentia died. Her legacy was carried on by Goebel but sadly in 2008, the Goebel Company shut down.

Perhaps you are experiencing a similar situation: our children do not collect nor want family heirlooms including Hummel figurines.

The Children

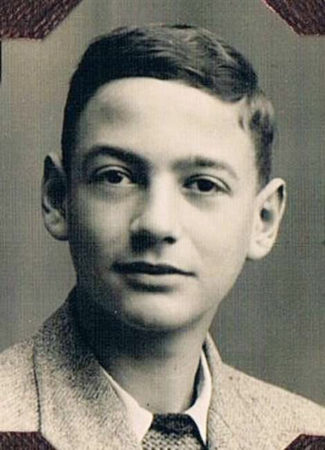

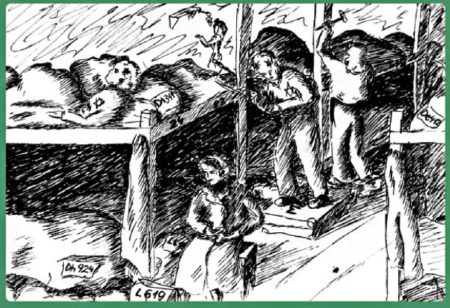

Thomas Geve

Thomas (b. 1929) was imprisoned in KZ Auschwitz-Birkenau at the age of thirteen. Upon arrival, Thomas was separated from his mother whom he would never see again. (His father had much earlier escaped to London and intended to have his family follow.) Tattooed on his arm was “127003” but as an inmate, Thomas’s name became “003.” For two years, Thomas managed to survive three concentration camps including the death march from KZ Buchenwald in 1945 as the Soviet army approached. Almost immediately after the war ended but before joining his father, Thomas drew more than eighty sketches from memory of Auschwitz-Birkenau and life in the camp beginning with his arrival.

Helga Weissová

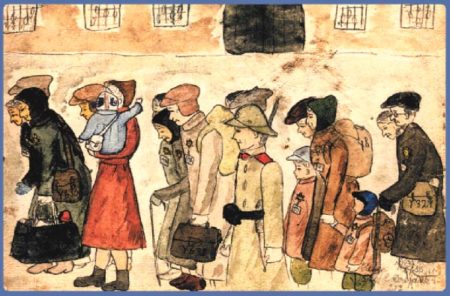

Helga (b. 1929) was thirteen when she arrived at Theresienstadt, a transit ghetto-camp in . More than 15,000 children were deported to Terezín with less than one hundred surviving. Helga was deported to Auschwitz II-Birkenau where she and her mother survived.

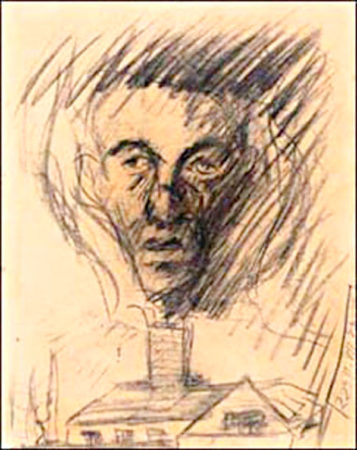

Yehuda Bacon

Yehuda (b. 1929) arrived at Theresienstadt in the fall of 1942. He and his father were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in December 1943. Yehuda was sixteen when he sketched the face of his father who had been murdered at the extermination camp in June 1944. Yehuda survived the camps as well as several death marches and lives today in Israel.

Edita Pollakova

Edita (1932−1944) was nine years old when she arrived at Theresienstadt. Deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, Edita was murdered upon her arrival on 4 October 1944.

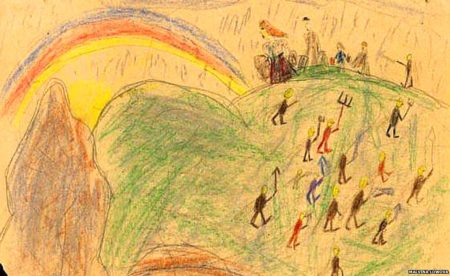

Malvina Lowova

Malvina (1932?−1944) was eleven when she drew the picture of her family being deported. One year later, she was killed by the Nazis.

Pavel Sonnenschein

Pavel (1931−1944) was deported to Theresienstadt in 1942 and two years later at the age of thirteen, sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau where he was murdered upon arrival on 23 October 1944.

Roman Halter

After the German invasion of Poland, Roman (1927−2012) and his family were deported to the Łódź ghetto. By 1942, all of Roman’s family were dead. He was transferred to Auschwitz-Birkenau where he was saved from extermination because of his skills as a metal worker. On the death march from Auschwitz in 1945, Roman escaped and eventually found his way to London. He went on to become a very successful architect.

Ruth Čechová

Ruth (1931−1944) was brought to Terezín on 19 March 1943. She produced thirteen drawings and watercolors before her deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1944. Ruth did not survive.

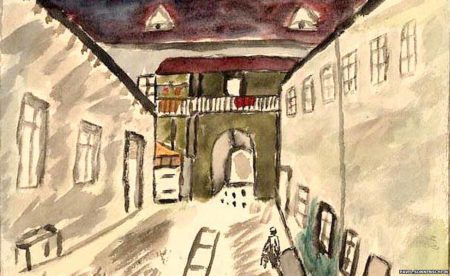

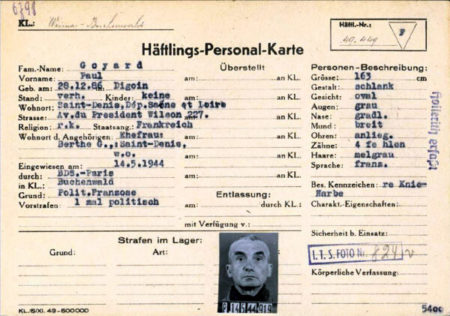

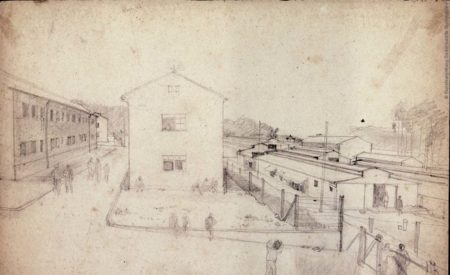

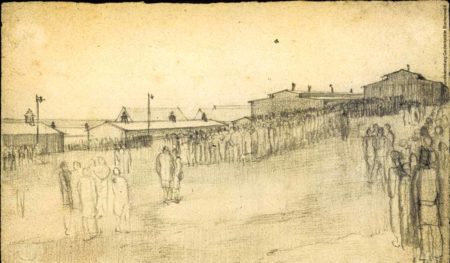

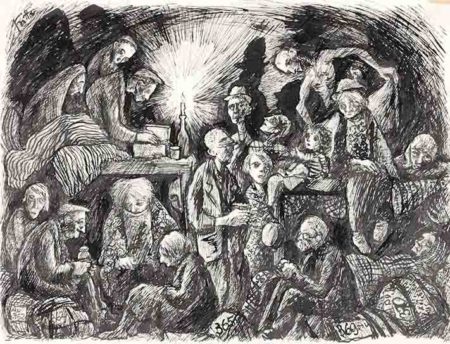

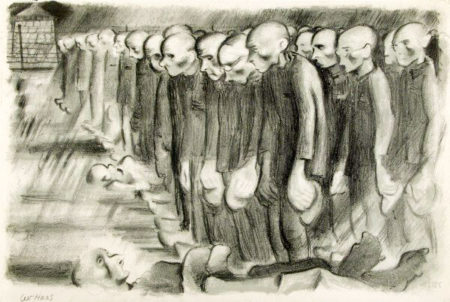

Paul Goyard

As a member of the French Resistance, Paul Goyard (1886−1980) was arrested by the Gestapo in 1942 and detained at the Compiègne internment camp. In May 1944, he was deported to Buchenwald as a “Political Frenchman.” Goyard was liberated by the Allies in April 1945. During his imprisonment at Buchenwald, Goyard produced three hundred pencil drawings about living conditions within the camp. After the war, Goyard and other camp survivors often met to collaborate on their works about Buchenwald.

Edith Birkin

Born in Prague, Edith Birkin (1927−2018) and her family were sent to the Łódź ghetto in 1941. Within a year, her parents died, and she was left alone. In 1944, the ghetto was liquidated, and the survivors were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Edith was selected for slave labor and sent to a labor camp in Bavaria. As the Soviet army advanced toward Berlin in the spring of 1945, Edith was moved to KZ Bergen-Belsen where she was liberated.

Bedrich Fritta

Bedrich Fritta (1906−1944) was a Jewish artist and cartoonist living in Prague when he was deported to Theresienstadt in December 1941. Upon being summoned to the camp SS headquarters, Fritta and other inmate artists hid their artwork including Fritta’s picture book prepared for his son’s third birthday. Fritta, his wife, and young son, Tomáš, were imprisoned in a Gestapo prison. Fritta’s wife died in the prison while Bedrich was deported on 8 November 1944 to Auschwitz-Birkenau where he was murdered shortly after arriving. Tomáš survived and inherited the picture book after it was discovered along with hundreds of inmate artwork after the liberation of Theresienstadt.

Friedl Dicker-Brandeis

Friedl Dicker-Brandeis (1898−1944) was a Jewish artist and educator who worked in Berlin and Vienna before moving to Prague in 1934. Friedl and her husband were sent to Terezín and the detention camp in 1942. While at Theresienstadt, Friedl taught drawing to hundreds of children. She made numerous sketches of camp life, and these were discovered in the 1980s and are now held by the Simon Wiesenthal Center. On 6 October 1944, Friedl was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and gassed upon arrival. After the war, more than five thousand pieces of artwork made in her classes were found. Most of them are now in the Jewish Museum, Prague and the Jewish Museum, Berlin.

Click here to watch Art Therapy Helped Children During the Holocaust.

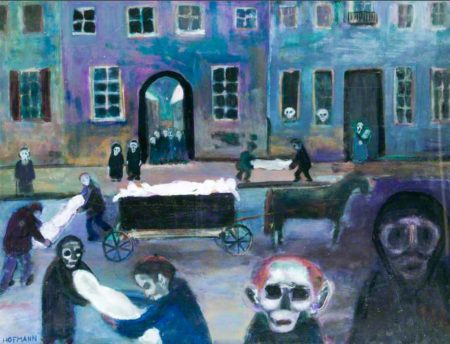

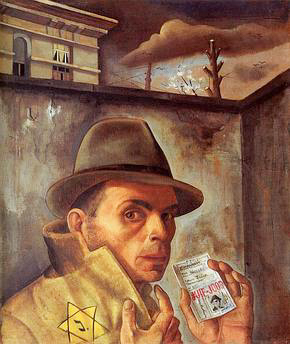

Felix Nussbaum

Felix Nussbaum (1904−1944) was a German-Jewish surrealist painter. After Hitler came to power, Nussbaum knew he could not stay in Germany and with his wife, moved to Belgium. Immediately after the Germans invaded Belgium in 1940, Nussbaum was arrested as a “hostile alien” German and interned at Saint-Cyprien in France. Put on a train back to Germany, Nussbaum escaped and met up with his wife in Brussels where they went underground for the next four years.

In 1944, Nussbaum’s parents were murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau and in July, the Gestapo arrested Nussbaum and his wife after finding them hiding in an attic. On 2 August 1944, they were put on the last convoy train to leave Brussels. After a short stay at a transit camp, the two of them arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau and within a week, were sent to the gas chamber. By the end of 1944, the entire Nussbaum family had been eliminated by the Germans.

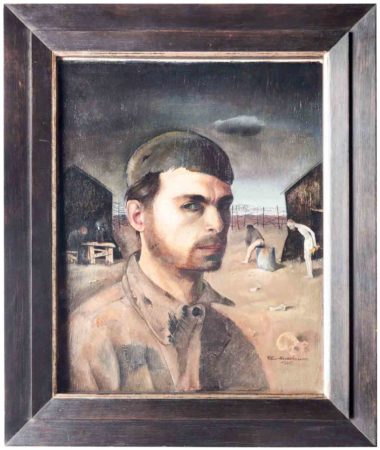

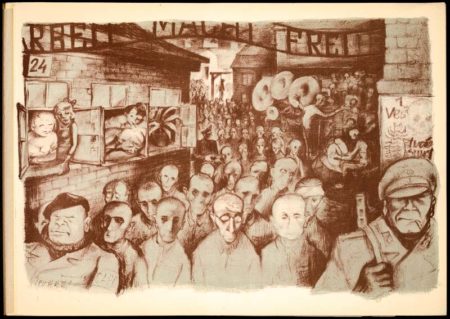

Leo Haas

Leo Haas (1901−1983) was a German painter and caricaturist living in Vienna during the interwar period. Haas was a Communist and in 1939, he was arrested and deported to a labor camp under Hitler’s Nisko Plan. Ultimately released, Haas and his wife were later (August 1942) deported to Theresienstadt where he joined a group of painters including Bedrich Fritta.

While in Theresienstadt, Haas was assigned to illustrate propaganda material for the Germans. During this time, Haas and the other artists painted or drew scenes of life in the camp. The clandestine artwork was discovered, and the artists were imprisoned in the infamous “Small Fortress” and brutally tortured. In October 1944, Haas was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau and a month later, to KZ Sachsenhausen where he was assigned to a unit counterfeiting currency. He was transferred to several other camps before his liberation on 6 May 1945 at Ebensee, a KZ Mauthausen sub-camp. Haas was the only survivor of the Theresienstadt artist community.

After the war, Haas returned to Terezín where he unearthed about four hundred drawings he had hidden while at Theresienstadt. Many of the portraits he drew of other inmates are now part of the Yad Vashem collection.

Next Blog (16 July): A Home Slide Show or “Stew and Sandy’s Summer Vacation”

★ Learn More About Concentration Camp Illustrators ★

BBC: “Haunting” Art by Jewish Children in WW2 Concentration Camp. Click here to read the article.

Browning, Christopher. Nazi Resettlement Policy and the Search for a Solution to the Jewish Question, 1939-1941. German Studies Review, Vol. 9, No. 3., pp. 497-519, 500; October 1986.

Copp, Jay. Hummel and Her Famous Figurines. Cincinnati: St. Anthony Messenger Press, 1997.

Fritta, Bedrich. Für Tommy zum dritten Geburtstag in Theresienstadt 22.1.1944. Pfullingen, Germany: Neske, 1985. In German.

Geve, Thomas with Charles Inglefield. The Boy Who Drew Auschwitz: A Powerful True Story of Hope and Survival. New York: Harper, 2021.

Haas, Leo. Leo Haas: Terezín 1942-1944. Praha: Oswald, 1983. In Czech and English.

Karl, Kaster G. Felix Nussbaum Galleries. New York: Overlook Press, 1997.

Stanić, Dorothea. Kinder im KZ. West Berlin: Elefanten Press Verlag, 1979. In German.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are back home after two fantastic weeks in Europe. Four days before we returned, the requirement for a negative COVID test to re-enter the states was abolished. Great but now we’re battling to get our US$100 back from the testing company.

It was a trip where we moved around a lot and the itinerary had many moving components. Happy to report that everything went off without a glitch. We met a lot of interesting people (see below) and had some “off the chart” dinners. The best mussels I’ve ever eaten came from a Glasgow restaurant. We stopped by our favorite seafood restaurant, Scott’s Restaurant, while in London. (The octopus carpaccio and Dover sole are to kill for.) Also in London, we found two excellent restaurants right around the corner from our hotel (i.e., Indian and Chinese). Speaking of hotels, they were all excellent.

So, now I’m working on some future blogs, tying up the loose ends of the trip, communicating with those whom we met, and getting ready for the grandkids to descend on us in a week. (By the time you read this, we will be in the pool with them.)

Our next blog (16 July) will be about our trip. Sandy took more than a thousand photos and I hope to put a few of them in the blog. Hope you’ll tune in again in a couple of weeks.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank some of the people who we met up with on our recent trip to Europe.

First, it was great to see Raphaëlle! She accompanied us to KZ Natzweiler-Struthof (south of Strasbourg) and once back in Paris, to the Bobigny rail station where deportations to Auschwitz-Birkenau began during in the summer of 1943. (Both of these sites will be featured in the second volume of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?) Finally, it’s always a pleasure to have dinner with Raphaëlle, Laurent, and their little girl, Alice. We had planned to do this three years ago but, well, you know what happened. Raphaëlle is our “go-to” guide in Paris and I highly recommend her if you are looking for a knowledgeable and credentialed guide. She can be reached at raphaellecrevet@yahoo.fr.

While in Strasbourg, we visited with Dominique Soulier at the MM Park military museum. (Dominique was kind enough to autograph my copy of his book, The Sussex Plan: Secret War in Occupied France, 1943-1945.) This is a World War II museum that I highly recommend you visit. I never knew the Luftwaffe had its own fleet of boats that were used to pick up their downed pilots in the English Channel. The museum has an original boat floating in a special water tank. The collection of military uniforms and guns is incredible. However, the museum’s collection of armored vehicles and large anti-aircraft artillery is stupendous. If you want to visit, contact me and I will introduce you to Dominique. Check out their web site at www.mmpark.fr.

A special thank you is reserved for Richard H.F. Neave. Richard is the president of the Royal British Legion, Paris Branch (RBL) and a member of Libre Résistance. (Richard provided a testimonial for the back cover of our recent book, Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?) We were invited to meet up with Richard and other members of the RBL and Libre Résistance at their Paris headquarters for cocktails before heading out for dinner with everyone. Listening to everyone’s stories was fascinating. We can’t wait to get back to Paris and build upon our new friendships. Please visit the RBL website (www.rblfrance.org) and the Libre Résistance website (www.libreresistance.com).

Last but not least, we had a wonderful visit with Roland Kennedy in Glasgow, Scotland. Roland’s father was one of the last British military men to leave Hong Kong before the Japanese invaded. (His escape is chronicled in Tim Luard’s book, Escape from Hong Kong.) Roland is an independent location scout for movies and documentaries. Thank you, Roland, for hosting us around Glasgow. It had been fifty years since I was last in Glasgow… too long.

I hope you will follow us with our next blog when we introduce you in greater detail to the sites and people described above.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2022 Stew Ross

Great job Stew. A truly remarkable and very moving tributes to these brave artists. The truth is like the sun and the moon. It always reappears in some form. Some may choose to look away but that makes no difference.

Hi Greg; Thanks for your comment. Yes, remarkable and very moving but mostly, very sad. STEW