As his body plummeted towards the Normandy landscape at 250 feet per second, Sgt. Hilliard was likely praying to God that his chute would open. He had been trained to clear the plane before pulling the cord. Sgt. Hilliard saw for only an instant that several of his crew mates managed to jump out of the damaged aircraft before it began its downward spiral and broke in two. Glancing up, he figured enough time had gone by to clear the damaged bomber. He pulled the cord and felt a rush of excitement and relief when the chute opened and caught the wind to slow down his descent. Those feelings were short-lived. Now he realized that he was at risk of being shot by the Luftwaffe attack fighters such as the Messerschmitt Me-109s and the Fw-190s or killed by the German’s anti-aircraft guns’ flak which had crippled his aircraft and worst of all, he had absolutely no control over the situation.

This is the story and fate of the top turret gunner, Hilton G. Hilliard (1920−1985), and the crew on the B-17F heavy bomber which was shot down over France on the evening of 29 May 1943.

ADVANCE NOTICE FOR

MY HALLOWEEN 🎃 PRESENTATION

30 OCTOBER 2024

“Cemetery Crawl: Unearthing Parisian Legends”

Meet Some Interesting Occupants

BONJOUR PARIS

Bonjour Paris members click here.

Non-members click here, $10 fee.

Did You Know?

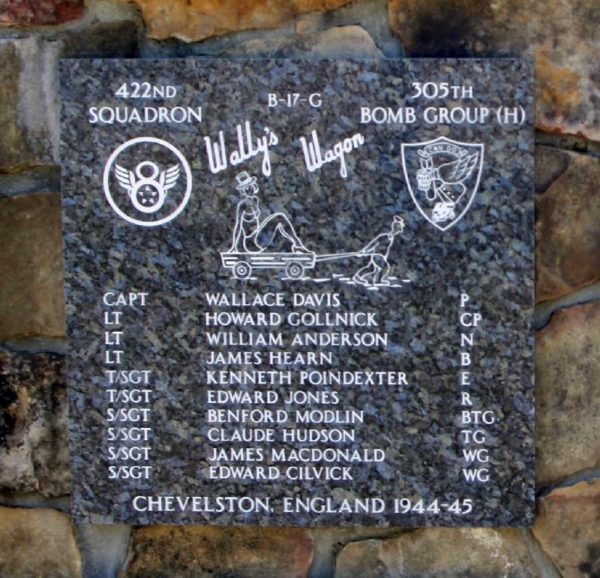

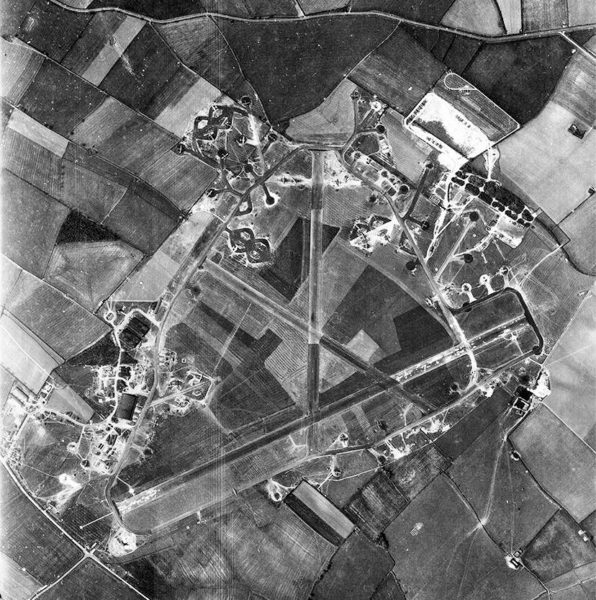

Did you know the 1949 film Twelve O’Clock High tells the story of the aircrews of the United States Army’s Eighth Air Force? Although a fictional story (the main character, Frank Savage, portrayed by Gregory Peck is loosely based on Colonel Frank Armstrong, who commanded the 306th Bomb Group), the film was generally recognized by former combat crews as one of the most realistic portrayals of the B-17s, their crews, and the hazardous missions flown out of English RAF airfields. For those of you who have seen the movie, you’ll remember it starts in post-war London when former Major Stovall (Dean Jagger) finds the Robin Hood toby mug in an antique shop. He purchases the mug, sets it in the basket of his bicycle, and peddles out to a country lane. Stovall stops next to a fence, gets off his bike, and gazes out to what is clearly a dilapidated airfield and flight tower that served as the fictional RAF Archbury. The scene then fades out and morphs into World War II as American B-17s are taking off for daylight bombing raids into Germany. The field he is looking at is the actual former RAF Chelveston airfield, base for the 305th Bomb Group and its four bomb squadrons including Sgt. Hilliard’s squadron. Today, the airfield has been developed into a renewable energy field. However, you can see traces of the old airfield when comparing the 1944 aerial photo to a current image.

Let’s Meet Hilton G. Hilliard

Hilton Hilliard was born in 1920 in South Carolina. His parents, William and Ruth Hilliard, moved their family of three boys and two girls to Dublin, Georgia where, except for his war years, Hilton spent his entire life. He was not quite six feet tall but had blonde hair and green eyes. Hilton was very handsome and could easily have been mistaken for one of Hollywood’s leading actors. In order to help support the family, Hilton dropped out of school after finishing eighth grade. A series of jobs led to his last vocation as a lathe turret operator prior to his enlistment in the United States Army Air Force (USAAF).

Once war was declared against Germany and Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the three Hilliard boys enlisted (Edward in the Navy and Lanier in the Army). Enlisting on 10 February 1942 at Fort McPherson in Atlanta, Georgia, Private Hilton Hilliard was sent to USAAF basic training for six weeks. The smart guys volunteered for aerial gunnery school because they knew it was the quickest way for a non-com to earn extra stripes and an increase in pay grade. After his training, Pvt. Hilliard was assigned to the Eighth Air Force and followed his unit from base to base until they were transferred to England and assigned to their permanent airfield, RAF Chelveston. See the Chelveston memorial here.

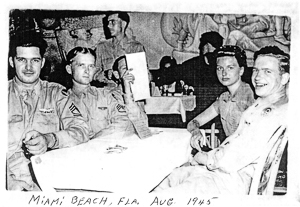

After his repatriation in 1945, Sgt. Hilliard mustered out of the army in Florida at Drew Airfield (now Tampa International Airport) and returned to Dublin where he married Gloria on 18 June 1949. They had two daughters, Susan (1952−2018) and Ann (b. 1961) and eventually, five grandchildren and ten great-grandchildren. Hilton retired in 1979 after many years working for the Dublin VA Medical Center; the last assignment as their Chief of Police. He was a member of the Moose Lodge and enjoyed fishing, rattlesnake hunting, and watching any Georgia sports team.

Mr. Hilliard passed away 10 June 1985 from heart failure at the young age of 65. (Over many years of research, I have come to find that many former POWs died in their sixties.)

Eighth Air Force

On 2 January 1942, the Eighth Air Force (“Eighth AF” or now known as the “Mighty Eighth”) was activated under the United States Army and the USAAF. The Eighth Bomber Command was established on 19 January 1942 with its mission to engage the enemy in strategic bombings using the B-17 as the primary heavy bomber. Right from the start, its mission was to support the inevitable Allied invasion of Europe, liberation of the Nazi occupied countries, and eventual push into Germany. Also within its structure was the Eighth Fighter Command (providing fighter escorts), Air Support Command (providing troop transport), and Air Service Command (logistical support).

See the B-17’s in action.

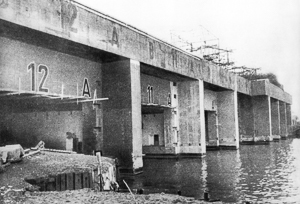

The Eighth AF arrived in Britain on 12 May 1942 and flew its first mission on 17 August 1942 with its last on 8 May 1945 (leaflet dropping). In between there were 984 combat missions. The first missions were flown in the daylight over France and the Low Countries hitting strategic targets such as U-Boat (i.e., submarine) pens, docks, shipyards, and motor works. On 27 January 1943, the bombers, including the 305th Bomb Group (BG), penetrated Germany for the first time.

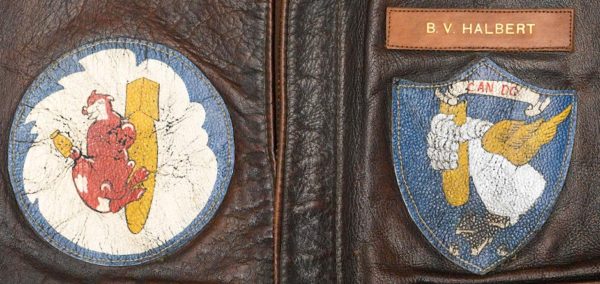

The 305th Bombardment Group was one of the heavy bomber groups assigned to the Eighth AF and the VIII Bomber Command’s 40th Bombardment Wing. It was known as the “Can Do” group. The 305th BG was assigned four bombardment squadrons: 364th, 365th, 366th, and the 422nd. Sgt. Hilliard and the crew flew a B-17F assigned to the 422nd Bombardment Squadron (BS). By September 1943, the 422nd was operating alongside the British RAF during night bombing missions over Germany. After D-Day, the 422nd returned to flying daylight missions.

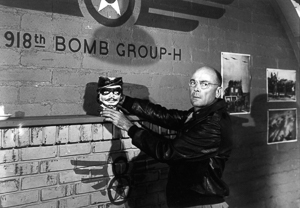

As part of the 1st Bomb Division, the tail marking for every B-17 assigned to the 305th was the giant “triangle G.” The 422nd squadron code (located on the fuselage above the wing) was “JJ.” Sgt. Hilliard’s B-17F carried the serial number 42-29531 located under the triangle G. We’re all familiar with military aircraft nose art illustrations (click here to read the blog Hot Stuff) and names given to the B-17s, however, most planes (including Sgt. Hilliard’s B-17) did not have the nose art or a name.

The men flying the B-17s were expected to fly twenty-five missions before being sent back stateside. Very few crews were lucky enough to reach their quota of missions. A total of 4,754 B-17s in the European theater were lost in the war with Boeing producing a total of 12,731 units between 1935 and 1945. The first B-17 to rotate back to the U.S. was the “Memphis Belle” (B-17F; SN 41-24485). Director William Wyler’s film crew went on board for the plane’s “last” mission and his 1944 documentary (Learn more: The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress) was widely shown around the country when the plane returned to the States to carry out a morale-building tour selling war bonds. It was also the subject of the 1990 movie Memphis Belle. (See below for more information and the link to footage of Hilliard’s plane going down filmed by Wyler.)

The Flying Porcupines

Colonel (later General) Curtis E. LeMay (1906−1990) commanded the newly created 305th between June 1942 and May 1943. Under his leadership, the 305th pioneered formation and bombing procedures that became the standard for the Eighth AF and other USAAF bomber commands.

During early 1943, the 305th was experiencing unacceptable losses (as were other bomber groups such as the 306th — the bomb group which Twelve O’Clock High was based on) and Col. LeMay began a rigorous training program which ultimately cut down the losses. He came to believe that many of the losses were a result of the bombers leaving the formation and ultimately becoming easy stray targets for German fighter aircraft. He developed the “bomb-group” formation which evolved into the “staggered combat box” formation. When executed properly, every plane was covered by the guns of contiguous B-17s. This flying formation provided the maximum fire power to combat any attacking fighters. The Luftwaffe fighter pilots called their attacks on the combat box formations as encountering fliegendes Stachelschwien or “flying porcupines.”

In the early days of Allied bombing missions, enemy fighters would attack from the stern (rear) of a plane. They quickly developed the alternative strategy of attacking from the “twelve o’clock high” position or straight on before pulling right or left to avoid collision. They felt the front of the B-17 was the most vulnerable. To counter this new Luftwaffe strategy, the next generation of B-17s (i.e., B-17Gs) would have a gun turret mounted below the plane’s nose. Click here to watch the video clip Memphis Belle.

The “bombing-on-the-leader” technique was introduced on 3 January 1943. Instead of each plane dropping its bomb loads individually, the planes would now drop their bombs in unison as soon as they saw the lead plane begin dropping its bombs. Typically, the best navigator and bombardier were part of the lead plane’s crew and this technique substantially increased accuracy.

Bomber Group Mission Number 61

Although the Eighth AF flew hundreds more missions before the war ended, Mission 61 was to be the ninth and last mission for Sgt. Hilliard and the rest of the crew. Shortly after the toby mug was turned around in the officer’s club, the bomber crews learned their next mission would be over Saint-Nazaire, France or “flak city” as the men called it. Their target was one visited many times by the 305th: the massive U-Boat pens. This was a strategic target and one of five major U-Boat pens located in the Atlantic ports of France. After the fall of France, Germany began the construction of the Saint-Nazaire submarine base. The concrete roof was thirty feet thick and able to withstand most bombs. The facility remains intact today and is being used for commercial retail purposes. Watch the Saint-Nazaire visitor’s guide here.

On Saturday, 29 May 1943 around two in the afternoon, Hilliard’s plane along with 154 other heavy bombers (seven of the new YB-40s were making their inaugural combat flight on this mission) took off from RAF Chelveston. Likely cruising in formation between 25,000 and 35,000 feet, they would be able to maximize fuel consumption at that altitude. According to the post-mission reports, the B-17 formations did not encounter any enemy fighters or flak as they swung out over the Bay of Biscay and then turning due east to Saint-Nazaire. At 5:06 PM, the first bomb was dropped on the Saint-Nazaire U-Boat pen and for the next five minutes, the planes unloaded their bomb bays. In his debriefing report (Escape & Evasion Report #64), Lt. Perrica, the bombardier, commented that the bombs were “direct hits.”

Once over the target, the bomb group met severe resistance in the form of enemy fighters and heavy flak. Sgt. Hilliard’s aircraft’s left wing was hit first by flak followed by a combination of continuous flak and gunfire from the Luftwaffe fighters. The plane’s fuselage and then tail section were hit next while gunfire from the Me-109s and Fw-190s shattered the B-17’s nose glass. Right after the bombs were released, the leading edge of the right wing between engine numbers three and four was hit and almost immediately, the number four engine was knocked out. Leaving the formation, Lt. Peterson banked the plane to the right to return to the base. By this time, the plane was hopelessly crippled, and the pilot gave the order to abandon the plane and bail out. No one needed Lt. Peterson to repeat himself. Eight of the ten crew members successfully bailed out. Sgt. Mathews was likely dead at this point having been hit by the bullets from an attack fighter. The plane went into a steep spiral pinning Sgt. Milasius on the floor. Around ten thousand feet, he managed to get to the door and jump out to deploy his chute.

The plane split in two in mid-air and crashed near the village of Saint-Bihy in the Department of the “Côtes d’Armor,” Bretagne Region, France (near the coast of northern France). Half of the crew landed several miles south of Quintin in Brittany. Sgt. Milasius landed in the middle of a village (Le Vieux-Bourg) about twelve miles southwest of Saint-Brieuc while Sgt. Freeborn landed in a field outside the village. Sgts. Hilliard and Smith dropped down in a field just outside a very small village called Le Cambout. They were south of where the other seven crew members had landed. All of them had a landing party waiting for them: Frenchmen from the nearby villages. However, the Germans saw the plane go down as well and they were on their way.

One month after Sgt. Hilliard’s plane was shot down, the Eighth AF sent 191 B-17s back to Saint-Nazaire. Officially, it was Mission No. 69. A total of 158 bombers hit their target: mission successful. Unfortunately, by that time, Sgt. Hilliard was a guest of the Gestapo in Paris.

The Crew–Escape, Evasion, and Capture

I began my research on this blog focusing on the crew. There have been a lot of rabbit holes I’ve gone down, but I think I’ve unearthed well-documented and correct information. Unfortunately, there are some missing gaps but hopefully, with further research I can fill those in. We’ll address Sgt. Hilliard’s situation separately. Most of the escaped airmen (from the POW camps) who successfully made their way back to the UK were never assigned another combat position. Instead, they gave lectures on evasion and escape to the squadrons using their own experiences. Weeks before Sgt. Hilliard’s plane went down, crews of the 422nd BS attended their evasion lecture.

Lt. Marshall R. Peterson Jr. (1921−2004) was the pilot. He successfully parachuted out of the plane and was immediately captured. Lt. Peterson remained a POW in Stalag 7A near Moosburg, Germany for the remainder of the war. He was repatriated and rose to the rank of colonel during a 31-year career in the Air Force.

2nd Lt. Harold E. Bentz (1921−2007) was the co-pilot. Based on his post-evasion report, I assume he landed in an area away from the others. There were Frenchmen in the pasture when he came down, but they ignored him. Lt. Bentz, who was fluent in German, hid in a ditch as German soldiers passed by. He walked all night and finally went to sleep in a field. When he awoke, a number of Frenchmen were standing around. One of them spoke English since he had once lived in Kansas City. They gave him money and civilian clothing. Lt. Bentz lost his map of France when he bailed out, but the Frenchmen pointed him north, so he began his walk on 30 June 1943. At one point, a French gendarme stopped him. The police officer took him to an English-speaking countess who gave Lt. Bentz a train ticket to Paris along with the contact information for her sister. She explained that her sister worked for the French Red Cross near Gare du Nord (one of the major rail stations in Paris). During the time he spent in Paris, Lt. Bentz came into contact with a minimum of four Resistance organizations. In early July 1943, Lt. Bentz was guided up and over the French/Swiss Alps by Ness, a former French fighter pilot. By 6 July, Lt. Bentz reached Switzerland. On the evening of 6 July, he was kept overnight in a jail cell at Porrentruy. The next morning, he was taken to Berne and interrogated over a six-day period. Lt. Bentz was finally turned over to the American legation (i.e.,the American diplomatic minister). According to policy, he was quarantined for 21-days before being sent to the RAF camp on Lake Geneva. Lt. Bentz spent many months in various camps working at various tasks for the consulate. On 23 August 1944, Lt. Bentz and several other officers bribed their guards and were able to return to France where the Maquis set up their transportation to Hauteville. Read the story of Nancy Wake and the French Resistance. There, they met up with the Seventh Army’s 45thDivision HQ on 2 September 1944 (the 45th was part of the invasion of Southern France on 15 August 1944). The evaders were flown to Naples and then to Casablanca on 7 September. The men arrived in England on 8 September 1944.

Lt. Lawrence F. Mandelberg (1921−unknown) was the plane’s navigator. Lt. Mandelberg was captured and sent to Stalag Luft 3 Sagan-Silesia Bavaria (this is the POW camp depicted in the movie The Great Escape starring Steve McQueen). This camp was exclusively for Allied officer airmen and was run by the Luftwaffe. Compared to other POW camps, the men were treated relatively well. On 27 January 1945 with the Russians advancing towards the camp, the prisoners were marched to various POW camps in Germany (the camp was located in what is today Żagań, Poland). Lt. Mandelberg was in the group that ended up at Stalag XIII-D Nuremberg-Langwasser. The camp was located on the Nazi’s former Nuremberg party rally grounds (refer to the blog, Zepplin Field). Less than four months later, Lt. Mandelberg was liberated after 728 days of imprisonment.

2nd Lt. Frank R. Perrica (1919−unknown) was responsible for dropping the bombs—he was the crew’s bombardier. Lt. Perrica bailed out of the aircraft after he saw the navigator jump and the pilot getting ready to jump. After clearing the damaged airplane, the number four engine exploded sending sharp metal shrapnel towards him. The metal pieces tore off his flying boot and cut away the heal of his G.I. boot. Hanging in the air with his chute open, two Fw-190s bore directly down on him and began to fire their guns. They made two sweeps before leaving—needless to say, Lt. Perrica was very lucky to survive. Other than the heel wound, he landed safely in a field where several Frenchmen began to help him. Lt. Perrica and three others had landed close to one another, and they decided to pair off and leave the vicinity. Lt. Perrica and S/Sgt Tafoya took off in a southwesterly direction and that evening slept in a ditch. The next morning, the two were given breakfast at a farm house and received instructions on the best route to take (they were still wearing their uniforms but had stripped off every insignia). Walking all day, they slept that evening in a barn. The next morning (31 May) they were near the small town of Loudéac. The Frenchwoman who fed them breakfast advised them to move on quickly as a large contingency of German soldiers were about to encamp in the area on their way to Bordeaux. They changed their direction in the afternoon to northeast but found themselves sharing the area with Germans. The two men found an area in the woods where they could sleep that night. On 1 June, they passed the village of Plemet and stopped at a farmhouse. Given sandwiches, Perrica was told they had about four hours before the Germans would catch up with them. They immediately left and once again, changed direction now to the southwest. Stopping at another farmhouse in the late evening, the men were given food and allowed to sleep in the barn. The next day (2 June), Lt. Perrica and Sgt. Tafoya continued their walk through the fields and in the late afternoon, approached a farmer to find out where they were. He invited them to stay at his house for several days and then put them on a train to Paris where they made contact with some of the farmer’s friends. These new buddies happened to be in the French Resistance and made arrangements for the downed airmen to get to Spain (through the Bourgogne escape line) and ultimately, back to England where they landed on 12 August 1943.

S/Sgt Peter P. Milasius (1911−1993) manned the bottom turret guns. The plane was in pretty bad shape with horrific vibrations pulling the aircraft apart as Sgt. Smith and Sgt. Mathews were putting on their parachutes. Sgt. Milasius crawled out from the bottom turret to find out what was going on. Sgt. Mathews was hit and passed out. Sgt. Smith jumped out the door hatch while Sgt. Freeborn should have exited from the bomb-bay but came running out the radio room instead—he didn’t want to jump. Sgt. Milasius had to push him out. At 10,000 feet, the bottom turret gunner finally jumped and at 3,000 feet, deployed his chute. He landed near a church in the town of Le Vieux-Bourg. Almost thirty Frenchmen surrounded him. He saw Sgt. Freeborn make a hard landing and he ran out of the village to find his crew mate. Sgt. Milasius’s story is very similar to the other evader stories. He was hidden by the French Resistance at various locations including Paris. It was in Paris that Sgt. Milasius was reunited with Lt. Perrica and Sgt. Tafoya. The men finally rendezvoused with one of the leaders of the Bourgogne escape line and went over the Pyrenes crossing the border into Spain on 31 July 1943. They arrived in Gibraltar on 11 August and then England on 12 August 1943.

T/Sgt Joseph J. Freeborn (1917−unknown) was the plane’s radio operator and flight engineer. After Sgt. Milasius rid himself of his parachute and equipment, he ran out of the village and found Sgt. Freeborn laying in a field. The radio operator landed so hard that he broke his leg along with sustaining multiple injuries including broken ribs and severe lacerations to the face. A French “Laval” policeman arrested Sgt. Freeborn as he was being carried to the hospital. (The term “Laval” was in reference to Pierre Laval, the Vichy prime minister – click here to read my blog, TIME Magazine’s Man of the Year is Executed). The next two years would be spent in Barracks 35A at the infamous Stalag 17B – Braunau Gneikendorf near Krems, Austria (Stalag 17B was used as the model for the 1953 film Stalag 17, starring William Holden). Sgt. Freeborn would eventually be liberated and repatriated back the United States.

T/Sgt Percy C. Mathews (1918−1943) operated another set of turret guns—he was the right waist gunner. Sgt. Mathews never made it out of the plane. One of the post-evasion reports by a crew member says that Sgt. Mathews was hit by the bullets from one of the enemy fighters. This is consistent with Sgt. Milasius’s story of the gunner passing out right after putting his chute on. In 2015, the remains of Sgt. Perry Mathews were found in the Brittony American Cemetery in St. James, France. It is believed to be the final resting place of Sgt. Mathews. Information I have indicated DNA testing was to be performed to confirm the identity of Percy Mathews. I have followed up with the people heading up this investigation and am waiting to hear from them.

T/Sgt George P. Smith (1920−1983) was the left waist gunner. Sgt. Smith was captured and spent the remainder of the war in Stalag 17B along with Sgt. Hilliard and Sgt. Freeborn albeit in different barracks—16B. Sgt. Smith was captured along with Sgt. Hilliard near the Spanish border. They had been betrayed to the Gestapo by a Frenchman at a train station. He spent time as a “guest” of the Gestapo in Paris before going to the Dulug Luft 12 for another round of interrogation and ultimately, Stalag 17B where living conditions were harsh. Liberated after two years of captivity, Sgt. Smith weighed only 119 pounds when he returned from captivity.

S/Sgt Salvadore S. Tafoya (1918−1960) rounded out the crew as tail gunner. Sgt. Tafoya’s story is very similar to that of Lt. Perrica since they traveled as a pair and were not separated. Sgt. Tafoya’s debriefing report conducted after the men successfully evaded capture and returned to England was marked by the reviewing officer as being the same as Perrica’s report. Sgt. Tafoya’s grave marker indicates he may have been assigned to the 339th BS after his repatriation.

The one thing each evader had in common was that they were all, at one time or another, taken to Paris and sheltered before being turned over to the men and women who ran the escape lines over the Pyrenes into Spain.

Rendezvous With The Gestapo

Sgt. Hilliard hit the ground probably harder than he would have liked—either you learn to roll, or you don’t. He saw Sgt. Smith land near him in the field. They decided to stick together and try to get back to England together. They spent the night of 29 May at a farm outside Le Cambout, a village consisting basically of a church and a café. The next morning, they left on bicycles accompanied by a Frenchman who stayed with them until their capture. They had been given civilian clothes, food, and documents (e.g., a fake passport) at the café in Le Cambout. Eventually, they were put on a train going south. Their train stopped near Dax, France, south of Bordeaux and just north of the French and Spanish border. The two men got off the train to wait in the baggage area. That is when the Gestapo agents approached and arrested them. The downed airmen had clearly been compromised by someone close to them.

Thirty-three years later after their arrest, one of the villagers from Le Cambout who assisted Sgts. Hilliard and Smith confessed that she and other Resistance members were concerned about the trustworthiness of the Frenchman who accompanied the two airmen all the way to Dax. Hilton Hilliard wrote back to her about a young man who shared their train compartment. This person, Hilliard wrote, was very nervous, wouldn’t look them in the eye, and grabbed his bag immediately once the train stopped and exited onto the station platform. Hilliard always felt it was this man who betrayed them to the Gestapo.

Held in the Dax jail for two days, Sgts. Hilliard and Smith were put on a train headed to Paris and the Gestapo headquarters at the French Ministry of the Interior (9-11, rue des Saussaises). Sgt. Hilliard asked them why he and his comrade were not being taken to a POW camp. The Gestapo replied that they had to determine whether the two men were airmen and not spies. Both men were arrested while out of uniform. The normal course of action for the Gestapo was to execute on the spot any enemy soldier caught in civilian clothes. After the war, Hilliard confessed that he was very lucky not to have been shot.

During his four months in a Gestapo cell, Sgt. Hilliard was kept in solitary confinement. Each cell was approximately 5 feet deep by 6 feet wide. They had wooden floors and one or two iron hooks on the walls to which each prisoner was chained. Sgt. Hilliard had plenty of time to read the graffiti scrawled on the walls from past prisoners. Using a sharp object, he carved his name into one wall. Sgt. Hilliard was interrogated (and likely tortured) about his French contacts, who issued his fake identification, and who assisted him. It was likely that the Gestapo also tried to get information about his squadron, targets, and other pertinent facts. Throughout these interrogations and threats of execution, neither Sgt. Hilliard nor Sgt. Smith cracked.

After four months, the Gestapo released both men to the Luftwaffe so they could be sent to Germany and a POW camp. Both men were ultimately assigned to Stalag 17B in Krems, Austria where they stayed until 8 April 1945. As the Russians approached, the Nazis abandoned the camp and the prisoners were marched almost 300 miles to a forest outside Braunau, Austria where they camped on 2 May. Gen. Patton’s Third Army and its 13th Armored Division (otherwise known as the “Black Cats”) was pushing hard to reach Berlin. They had crossed the Regen and the Danube rivers and finally on 28 April 1945, crossed the Isar River in Bavaria, Germany. (Eighteen months later, the Nuremberg main trial was completed and the cremated remains of eleven former Nazis leaders were dumped into this river.) Four days later, the armored division entered Braunau am Inn, Austria and set up their headquarters in the house where Hitler had been born. About this time, the ragged, weary, and hungry former POWs were discovered in the forest and liberated from their German captors who immediately surrendered without a fight.

Notable B-17s, Pilots, and Crews

You won’t find Sgt. Hilliard, any of his crew mates, or the 42-29531 on any lists of notable B-17s or their crews. What you will find are the official government statistics on the 42-29531’s history, the plane’s mission and its MIA status, and the outcome of each crew member after the plane being hit. Theirs is a story of ten very brave young men going to work every day knowing it might be their last. It’s a story that can be repeated thousands of times but with different names.

The real story doesn’t end with the repatriation of the five POWs, the successful evasion of four members of the crew, or even the eventual identification of Sgt. Mathews’s remains. It really never ends. The children of these men are now the keepers of their scrapbooks and memories. Each of these children deal with the memories in their own different way.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

There are hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of individual stories about men and women who fought or lived through the German occupation of their countries during World War II. I have known some of the men who came back from both fronts (European and Pacific) and I have talked with others who were familiar with first-hand accounts. Many of the returning soldiers (my Uncle Pete), sailors (Uncle Bill), and airmen (Uncle Hal) never talked about the war again or at least until they were well into advanced age. Frequently, they would relate their stories to the grandchildren and only then would their sons or daughters hear these stories for the first time. In many instances, there were no stories, and it wouldn’t be until the children (or widow) would find, for the first time, an old steamer trunk, open it, and find his World War II memorabilia including the medals and commendations. Unfortunately, some of the returning veterans came home with psychological issues that negatively affected them for the remainder of their lives along with their families and co-workers. (One of the best movies that dealt with these issues was William Wyler’s 1946 film, The Best Years of Our Lives.)

Sgt. Hillard’s story doesn’t end with his repatriation to the United States and his family. During his post-war years, Mr. Hilliard suffered from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This is a disability brought on by the re-experience of a trauma of a past recognized stress. This re-experiencing can be one of the following: (a) recurring and intrusive recollections of the event; (b) recurrent dreams or nightmares; and (c) sudden feelings that the trauma was occurring because of an association, an environmental or ideational situation. Also involved is reduced involvement with the external world, beginning after the trauma, revealed by at least one of the following: (a) hyper alertness or exaggerated startle response; (b) sleep disturbance; (c) guilt about surviving when others have not; (d) memory impairment or trouble concentrating; (e) avoidance of activities that arouse recollection of the traumatic event; and/or (f) intensification of symptoms by exposure to events that symbolize or resemble the traumatic event.

Do you remember the scene in the movie Patton when Gen. Patton (played by George C. Scott) slaps the private in the field hospital? Patton slapped him because he thought the private was a coward. This was based on a true story but after the war, it was determined the private was suffering from PTSD (at the time, I believe it was called “battle fatigue”).

Another example is Jimmy Stewart, the actor. Mr. Stewart was a B-24 Liberator pilot and wing commander. He suffered extreme PTSD as a result of losing hundreds of men under his command—many were personal friends— as well as civilian casualties caused by the bombs dropped from his plane or those commanded by him. At one point, Mr. Stewart was considered “flak happy” and sent to the “flak farm.” Being “flak happy” was what is now known as PTSD and the “flak farm” was a treatment center for soldiers (the term “shell shock” or “battle fatigue” described similar symptoms during World War I). After the war and leaving active duty, Mr. Stewart’s first film was It’s a Wonderful Life. Production had to stop from time-to-time to accommodate his nightmares and symptoms of PTSD. The actor in him managed to channel many of the PTSD effects into his character, George Bailey—watch the movie and see if you can identify some of the symptoms the actor incorporated into his character.

The slapped private, the Hollywood actor, and Mr. Hilliard were not the only soldiers affected by PTSD during and after World War II. It’s a story that never really received much notice but now needs greater exposure.

Apologies

This blog is long compared to most of my other ones. Believe it or not, I’ve given you the abridged version of Sgt. Hilliard’s story. I didn’t even go into what it was like being a POW at the various Stalag Lufts. Nor did I go into depth about Sgt. Hilliard’s detailed travels to the various POW camps after the Gestapo decided to release him back to the Luftwaffe or his march out of the camp as the Russians approached. You haven’t heard the real story of Mr. Hilliard’s life after the war. You see, Mr. Hilliard always told his daughters that he felt what he and the others did during the war went unappreciated. That may be true at the time for several reasons. I’m not sure the generations under us have really been taught about the sacrifices these men and women made during World War II or realize how their actions impacted future generations, our freedom, and the freedom of occupied countries. It was almost like the men and women of World War II gave up the best years of their lives. They certainly earned the title of “The Greatest Generation.”

The Robin Hood Toby Mug

The Robin Hood toby mug previously mentioned is a fictional mug created by Fox specifically for the film Twelve O’Clock High. It is based on the description given in the 1948 novel of the same name by Sy Bartlett and Beirne Lay, Jr. and modified so that they didn’t run into any copyright or royalty issues with Dalton, the manufacturer of “real” toby mugs. The Robin Hood toby represented the mugs that sat on the shelf of the officer’s clubs. When it’s face was turned around to face the room, the B-17 crews knew a mission was forthcoming. Only two Robin Hood mugs were created for the film and one of them was presented to Colonel Frank Armstrong. It was stolen in the early 1990s and its whereabout is unknown. The second mug was broken and could not be repaired. Copies were made in 1994 and 1999 to commemorate the 45th and 50th anniversaries of the film.

Origin of this Blog

I wrote this blog after being contacted by Hilton’s daughter. She wanted to know if I knew which Gestapo cell her father had been held for those four months before being sent to the POW camp. Ann was determined to visit the cell and see the inscription her father wrote on the wall.

Naturally I didn’t know where Sgt. Hilliard had been held, prison or cell. So, I decided to do some detective work. Despite working many angles, we struck out each time and eventually, I had to tell Ann it was not possible to find the cell.

Six months later, I was researching our blog, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (click here to read the blog), when I ran across a book that mentioned Sgt. Hilliard and his inscription. You can imagine my excitement! I immediately began to work backwards from that point and found a book that answered our question. Henri Calet, a French poet, took it upon himself immediately after the liberation to go into the infamous Fresnes prison and record prisoners’ inscriptions. He wrote Les Murs de Fresnes and on page 29 there it was

DEUXIÈME DIVISION

Cellule 44

“S. Sgt H. Hilliard

June 1943

God bless America

Post Script

After publishing the original blog, Greg Smith and I began to correspond about the story of his father’s journey through World War II. Greg was left with memorabilia that he shared with me including a sketch of his father done by another POW. Greg’s research unearthed a German website where a photo of his father’s B-17 is posted. The plane had just arrived in England from the U.S. and only the tail number is painted on the aircraft confirming it is the B-17 that Hilliard and Smith were on. At that point, the plane had not been assigned to a BS. According to the research department at the Mighty Eighth Museum, the photo was likely taken by a local citizen working for the Germans as a spy (click here to read the blog, Agent Jack, “M” and the Fifth Column).

Click here to visit the Mighty Eighth Museum web-site.

However, one of the most amazing “finds” for Greg was locating the image of his father’s B-17 going down after being hit by flak and enemy aircraft firepower after the raid on the Saint-Nazaire U-Boat pens. You can see at least one of the men in the air right after bailing out. The still image came from William Wyler’s 1944 documentary, Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress. Although billed as the story of the Memphis Belle’s last mission, Wyler filmed the crews’ second to last, or 24th mission. The other thing to know is that a lot of the action footage Wyler used was a compilation of other missions and planes. In fact, Wyler was filming from a different B-17 on 29 May 1943 (the Belle had already returned to the states) when one of the nearby planes was hit and began its death spiral. He managed to film it and included the footage in the documentary. That plane was the B-17 that George Smith and Hilton Hilliard bailed out of after their successful bombing run. The image was captured in an award-winning painting by Steve Ingraham (a copy of which can be purchased if you contact Steve at saingraham@hotmail.com). Through his discussions with Mr. Ingraham, Greg was able to piece together the puzzle about the origin of the photo as well as confirm Wyler’s presence during the Saint-Nazaire mission on 29 May 1943. Click here to watch the documentary Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress.

Next Blog: “Pardon me boy, is that the Chattanooga Choo Choo?”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Bartlett, Sy and Beirne Lay, Jr. Twelve O’Clock High. New York: Harper & Brothers (1948; hardcover) and Bantam Books (1949; paperback).

Calet, Henri. Les Murs de Fresnes (“The Walls of Fresnes”). Paris: Les Éditions des Quatre Vents, 1945.

Goldwyn, Samuel (producer). The Best Years of Our Lives. Samuel Goldwyn Productions, 1946.

Puttnam, David and Catherine Wyler (producers). Memphis Belle. Warner Bros., 1990.

Snyder, Steve. Shot Down: The True Story of pilot Howard Snyder and the Crew of the B-17 Susan Ruth. Seal Beach: Seal Beach Publishing, LLC, 2015.

Sturges, John (producer). The Great Escape. The Mirisch Company, 1963.

Wilder, Billy (producer). Stalag 17. Paramount Pictures, 1953.

Zanuck, Darryl F. (producer). Twelve O’Clock High. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation, 1949.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are on holiday. We hope you enjoy this reprint of our 2018 blog, Rendezvous with the Gestapo. The story of Hilton Hilliard is one of our more requested lecture topics.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Over the years, we have received quite a few emails from people who are relatives of the men and women who appear in our blogs. This particular 2018 blog generated many emails from relatives of the men who served with Hilliard Hilton on the ill-fated B-17. Ann Hilliard Ussery contacted us initially with a simple question that ultimately turned into a six-month quest to find the answer and led to this blog topic. Greg Smith first contacted us about his father, George Smith, and we have become good friends. Indirectly several other relatives learned of the blog and were able to connect with Greg, Ann, and myself.

We were recently contacted by M. Didier Moreau. He is a relative of several Bourgogne escape line helpers who aided Sgt. Milasius during his journey to safety. He recently found a picture of Sgt. Milasius with Pauline Bringuet and her son, Pierre Moreau in Saint-Quay-Portrieux. I have requested a copy to include with this blog reprint. Hopefully M. Moreau will send me the photo in time to include it in our blog today.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please contact Stew directly for purchase of books, Kindle available on Amazon. Stew.ross@Yooperpublications.com or Contact Stew on the Home Page.

Shepherd.com is like wandering the aisles of your favorite bookstore.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf on WWII.

Check out Stew’s bookshelf on the French Revolution.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2024 Stew Ross

Thanks for this exceptionally detailed account Stew. It provides answers to a lot questions I still had with respect to several other members of the crew, as well as the circumstances surrounding the loss of B-17 JJZ Serial No.4229531. Although my father rarely mentioned his military service, once, I did overhear him describing how the plane was attacked by German fighters after being hit and disabled by anti-aircraft fire. Your more recent research reconfirms his own first-person account. There is no doubt in my mind that my father also suffered from PTSD.

Hey, Stew… Me again. Would you please send me a printed copy of this article. I’d like to include it with my dad’s WWII memorabilia. Unfortunately, I can’t print it directly from this website. My mailing address is: 926 Gardner Ave., Ventura, CA 93004. Thanks-A-Heap

Hi Greg, Thanks for your comments. I knew you would be the first. I have a feeling that most everyone who encountered combat (on land, sea, or air) probably came home with PTSD. We will get you a copy of the blog. STEW