I’m very pleased to present John Winn Miller’s guest blog for you today. John is the author of the recently published book, The Hunt for the Peggy C, a suspenseful novel set during World War II. His blog talks about five interesting topics he came across while researching the book. I was honored when John asked me to read an advance copy of the book and it turned out to be one of those books I couldn’t put down until finished. It was then that I asked him to consider writing a guest blog for us. John is a “Master of Research,” and I am confident you will not only enjoy this snapshot into his research but will learn some interesting facts. With that being said, I will now turn it over to John. (John’s bio can be found at the end of the blog as well as links to purchase his new book.)

Click here to see John’s book.

I have devoured countless World War II histories over the years. And I have been a fan of almost every documentary, movie, or television show about the era. So, naturally, I thought I knew a lot about the subject. That was until I started to write my debut novel, The Hunt for the Peggy C. The story is about an American smuggler who struggles to rescue a Jewish family on his rusty cargo ship, outraging his mutinous crew of misfits and provoking a hair-raising chase by an unstable U-boat captain bent on revenge.

I had never been on a U-boat or a tramp steamer and knew next to nothing about life at sea. So why did I pick this subject, you might ask? Strangely, I didn’t. It picked me. Years ago, I had been watching a terrible action-adventure movie (I don’t remember which one) with my young daughter Allison (who now plays Maggie on ABC’s A Million Little Things), and I kept telling her, “I know I could write a better screenplay than this.” That night I had a dream, and when I woke up, I knew the first scene, the last scene, and the name of the ship. That was all.

So, like Michelangelo used to say, I knew there was a figure in that block of stone–in my case, a story–and all I had to do was spend years trying to chisel it free. The screenplay I wrote received some interest in Hollywood but no sales. When COVID hit, and I was stuck at home with my wife Margo, two standard poodles, and a Maine coon cat, I decided to turn the script into a novel.

That is when I learned just how little I knew about the war. As a result, I spent months reading histories, websites, historical archives, and first-hand accounts and watching documentaries and YouTube videos. I wanted all the history and technical details–and there are a lot of both–to be accurate. I even went so far as to study wartime logs by U-boat captains so I could accurately describe the moon’s stage during each phase of the chase at the heart of The Hunt for the Peggy C.

Every day, I seemed to come across something that would make me exclaim, “Wait. What? I had no idea about that.” So, thanks to Sandy and Stew, I’d like to share five of those surprising discoveries with the readers of this wonderful blog.

“Blow the Man Down”

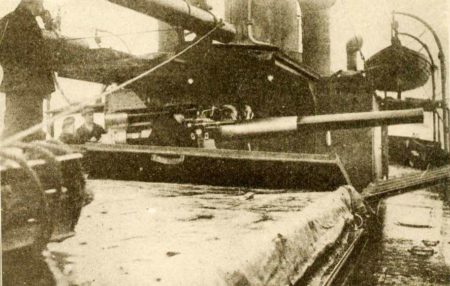

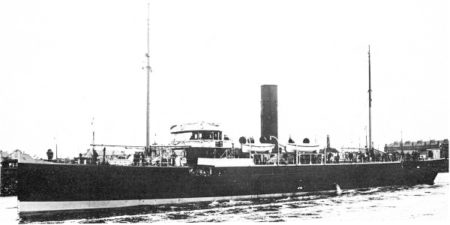

I had no idea that Hitler had pirates roaming and pillaging on the Seven Seas. And I was even more surprised to learn who originated the idea: Winston Churchill. Let’s start at the beginning. In November 1914, First Lord of the Admiralty Churchill desperately needed a more effective weapon against German U-boats strangling the island nation’s vital supply lines over the North Atlantic. Churchill’s solution was a top-secret plan to create “mystery ships” for a ruse de guerre, or deception: heavily armed warships disguised as harmless merchant vessels to lure unsuspecting U-boats to surface in the range of fire.

At the time, the U-boats complied with international Prize Rules about surfacing and giving merchant ships ample warning to safely abandon ship. That made the U-boats vulnerable to attack by Churchill’s Q-ships, believed to have been named for their home port of Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland. Their total number of Q-ships and how many ships they sank is a matter of some dispute, but some sources say there were as many as 200 of what the Germans called “U-Boot-Falle,” or “U-boat trap” from 1915-1917; they were credited with sinking around fifteen U-boats, less than 10 percent of the U-boats sunk in the war. Germany built six versions of the Q-ship, but none sank a submarine.

One unintended consequence of the British Q-ships was that their existence eventually drove the Germans to treat almost all merchant ships as hostile, possibly leading U-20 to torpedo the passenger ship RMS Lusitania without warning, killing 1,918 civilians.

Britain revived Q-ships at the beginning of World War II but abandoned them as ineffective early in the conflict. Germany, on the other hand, fully embraced the tactic. The Nazis called their nine disguised surface raiders Auxiliary Cruisers; others called them “Hitler’s Pirates.” They were the bane of merchant ships, armed or not, on the Seven Seas, collectively sinking or capturing 140 ships totaling close to a million tons. They did it with mines – most carried more than 200 of them – and their arsenal of torpedoes, machine guns, and cannons hidden behind fake bulkheads.

Some even carried two flimsy Heinkel He114B seaplanes hidden in the holds for scouting for targets. To avoid detection, the raiders changed their identity often, using fake funnels, paint, and neutral flags to match the description of ships listed in Lloyd’s Register of Shipping.

Most of the captains of what some called “high seas Houdinis” followed the Prize Regulations (sometimes called Cruiser rules). But one acted more like a true pirate. Kapitän zur See Hellmuth Max von Ruckteschell, one of the most successful and highly decorated of Hitler’s pirates, rarely fired a warning shot. Instead, he would open fire at the merchant ships’ bridge, killing and wounding several crew members before they knew they were under attack. After the war, he was one of only two German naval officers to be convicted of violating the rules of sea warfare for continuing to attack a ship after it had surrendered and for failing to make provisions for the safety of survivors. Von Ruckteschell, who died in prison, was not charged with attacking merchant ships without warning because Britain was known to arm them. Once again, one of Churchill’s whacky ideas had unintended consequences.

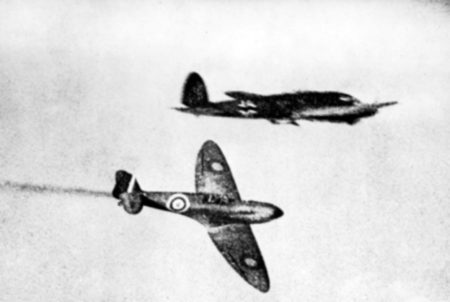

A Secret that Powered England’s Victory in the Battle of Britain

Shortly after the three-month-long Battle of Britain ended in October 1940, the Royal Air Force’s Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder publicly said three things led to victory: the bravery and skill of the pilots, the Rolls Royce-made engines, and “the availability of suitable fuel.”

Fuel? What was he talking about, I wondered? Turns out it was British Air Ministry 100. The BAM 100-octane aviation fuel, developed by Sun Oil and adapted for British airplanes by Standard Oil of New Jersey, gave the modified Merlin engines of British Spitfires and Hurricanes 30 percent more horsepower for taking off and climbing. They also could fly 25-34 miles per hour faster than they did over Dunkirk, an improvement in performance that startled and befuddled German pilots.

The Germans quickly figured out what Tedder meant when they discovered the fuel– dyed a distinctive green so it would not be confused with other fuels–in a downed Spitfire. But they couldn’t adapt their warplanes’ engines to the higher-octane fuel and were stuck using the less efficient 87-octane gasoline, derived mainly from coal.

The Paradox of the Jews in The Netherlands

I found it ironic when I discovered that Holland was the only German-occupied country where there were mass protests against the Nazis’ treatment of Jews AND the country with the worst record in Western Europe for the deportation and extermination of Jews. How was that possible?

Sephardic Jews and Marranos (Jews forced to convert to Christianity) started immigrating to Amsterdam in large numbers at the end of the fifteenth century to escape persecution and forced conversions in Spain and Portugal. They were followed in the seventeenth century by Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe, who called the city “Mokum” in Yiddish. Sephardic Jews spoke Ladino, a hybrid of Spanish, Hebrew, and other local languages. After Hitler came into power in 1933, more than 25,000 Jews fled Germany and took refuge in Holland. By the beginning of World War II, there were some 140,000 Jews in the country, with the majority in Amsterdam.

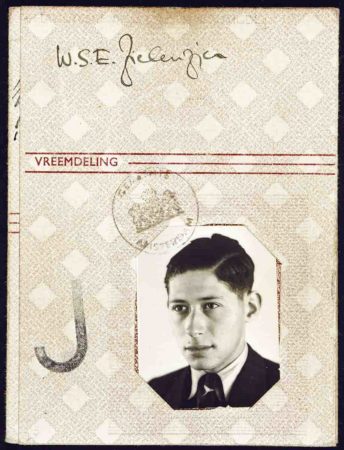

After the Nazi invasion in May 1940, Jews were subjected to steadily increasing persecution. They were forced to carry identification papers with “J” for Jew (wearing the yellow Star of David did not start until 1942), banned from many public places like parks, and fired from government and university jobs. Frequent fights broke out among Jewish self-defense groups and the Dutch fascist party Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (National Socialist Movement or NSB), especially members of its military wing of black-shirted young men called the WA, short for “Weerafdeeling,” which could have a double meaning of Defense Department or Weather Department, an allusion to Germany’s storm troopers. (Some books say WA stands for Weerbaarheidsafdeling, meaning Resilience Department.)

During one of those fights in February 1941, a WA member was wounded and later died. The Nazis retaliated by encircling the old Jewish neighborhood with barbed wire. Then Dutch and German police with the Gestapo raided an ice cream parlor named Koco, where several of them were injured. The raid was led by a newly promoted Untersturmführer (lieutenant) named Klaus Barbie, who would later become infamous as “The Butcher of Lyon.” In retaliation for the injuries, Barbie had 425 Jewish men rounded up and deported to concentration camps (only two survived). That triggered a nationwide strike on February 25 to protest the Nazis’ treatment of Jews. Hundreds of thousands of workers walked off their jobs and marched in protest. Surprised by the demonstrations, the Germans took three days to put an end to them by shooting into crowds and tossing hand grenades at them.

After the protests ended, the Nazis, with the support of the Dutch fascists, stepped up the persecution and deportation of Jews. By the war’s end, 105,000, or 75 percent, of the Jews in Holland had been killed. It was the highest total and percentage of deaths for Jews in Western Europe, outside of Germany. (The death rate was 40 percent in Belgium, 25 percent in France, and almost zero in Denmark, whose people smuggled nearly all of its 8,000 Jews to neutral Sweden.) The question remains: why did the land where so many Jews found refuge and acceptance end up being a death trap?

Part of the answer is geography. The Jews had nowhere to hide; Holland is flat and has no mountains or extensive forests. And it was surrounded by German-occupied countries, which, even in the days before the war, would not accept many Jewish refugees. The Dutch bureaucracy was cooperative with the occupiers and highly efficient–all citizens were registered by religion. The Germans also appointed a Jewish Council, Joodsche Raad, whose members advised Jews that obeying German rules would be the best way to avoid more reprisals. And most Dutch Jews were ordered to leave their homes and move to Amsterdam, where they were easier to control and round up. In addition, Dutch identification papers were nearly impossible to forge.

One final thing made Holland unique: bounty hunters. In 1943, the Germans began offering a reward for the capture of Jews. Leading the hunt were 54 members of the Colonne Henneicke led by Wim Henneicke, a thirty-three-year-old former taxi driver and auto mechanic with underworld connections. During seven months of operation, Henneicke and his band of thugs rounded up more than 8,500 Jews. They received an average salary of 230 guilders a month plus substantial overtime in addition to the money they made off the books by bribery and stealing confiscated Jewish possession. That was an enormous increase from the 60 guilders a month many of them had received on welfare. They were also paid kopgeld (head money) of 7.5 guilders for each Jew; the bonus was doubled for anyone caught in hiding or violating other anti-Jewish laws, “penal cases” they were called.

Henneicke got his final reward on December 8, 1944, when someone shot him five times and killed him.

The Strange Case of Captains Kusch and Abel

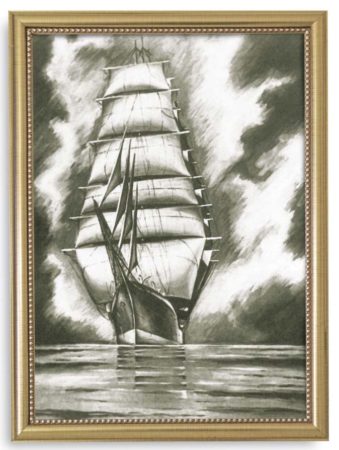

As I was researching U-boats and their captains for my novel, I was surprised to stumble across the story of the only U-boat captain in history, to have been executed by the Germans. I was even more astonished by the role played by Adolf Hitler’s photo and the drawing of a three-mast schooner.

The fateful drawing was by Oberleutnant zur See Oskar-Heinz Kusch, the only child of a wealthy, liberal-minded Berlin family, who excelled in school academically, in art, and in water sports. He also developed a loathing for the Nazis and their suppression of civil liberties, the mediocrity of its leaders, and the persecution of Jews. In 1937 at 18, the tall, movie-star-handsome blond fulfilled a lifelong dream by joining the Kriegsmarine, the German navy, and excelled in training and during brief service on a light cruiser.

In June 1941, he began his first tour of duty on a U-boat as second watch officer of U-103. During multiple voyages on the ship, he was promoted, awarded the Iron Cross First and Second Class, and was highly praised by his superiors for being tenacious and having “vast intelligence.” Fellow officers described him as “strongly built,” “a very good athlete,” and “a very sensitive young man.” The Lords, as enlisted men on U-boats were called, also sang his praises. “Kusch inspired his men and never pulled rank or acted the conceited big shot,” was how one described him.

Life aboard U-boats was harsh and dangerous; some 68 percent of the 40,000-50,000 men who served in them were killed or captured, by far the highest casualty rate of any branch of service. In compensation for the danger, U-boat crews received wages almost double other military branches. They were provided the highest quality food onboard and onshore, including the best wine, beer, and bordellos. During shore leave, they traveled in luxury on a special train known as the BdU Zug reserved for submariners for weeks of rest at home or at specially assigned resorts called “U-boat pastures.”

Most U-boat crews thought of themselves as above politics, as carrying out orders for the Fatherland, slaughtering civilians and naval enemies with the same efficient indifference. They were proud sailors of the highly selective U-Bootwaffe, not merely of the Kriegsmarine. And like Roman legionnaires, their loyalty was more often to the officers and men of their U-boat, not the Third Reich. Kusch relished that camaraderie and the atmosphere of free-wheeling discussions of politics and military strategy, knowing his fellow U-Bootfahrer had his back.

He had not counted on Oberleutnant zur See Dr. Ulrich Abel, the first watch officer assigned to U-154 when Kusch took command in January 1943. Abel was six years older than Kusch and a self-made man. He had joined the German merchant marine before earning his law degree and becoming a naval reserve officer in command of a minesweeper. He was also an ardent member of the Nazi Party. Throughout the first voyage to South America, Abel and Kusch constantly clashed over politics and tactics. At the end of the trip, Kusch submitted a less than enthusiastic evaluation of Abel, calling him rigid, one-sided, and an officer of “average abilities.” That infuriated Abel because it meant he would not get an independent command and would be stuck on another mission with Kusch on U-154.

At the end of that voyage, Kusch submitted a slightly more positive evaluation. But Abel was so fed up that he filed a three-page complaint in January 1944 against Kusch, charging him with being unfit for command because he was “strongly opposed to Germany’s political and military leadership,” listened to foreign radio broadcasts and lacked “an aggressive spirit against the enemy.” The very first of his eleven charges alleged that Kusch had ordered the removal of a picture of Adolf Hitler from the officers’ mess and replaced it with a painting Kusch had done of his family’s yacht, a three-mast schooner. Abel named five officers and sailors who would back him up.

Much to his surprise, Kusch was tried and convicted by a military tribunal. Although the prosecutors recommended a ten-year sentence, the three-judge panel sentenced Kusch to death. He was executed by a firing squad on May 12, 1944. (The year before, another U-boat captain, Kapitänleutnant Heinz Hirsacker, had been sentenced to death for cowardice but committed suicide before he could be executed.)

Ironically, Abel did not live to see Kusch’s execution. Three weeks before, he had set sail on his first patrol as commander of U-193. The next day, all contact was lost, and all 59 men aboard have been missing ever since.

Where in the Heck is a U-boat’s Steering Wheel and Other Mysteries?

I spent months reading about U-boats, studying diagrams and pictures, and watching documentaries. I did not pay much attention to movies because I learned that most–with the possible exception of Das Boot–were riddled with mistakes and exaggerations. And many of the books I read left out crucial details like “how do you actually steer a U-boat?”

But before I answer that question, let me tell you about some of the other surprising things I learned (in no particular order).

***

Nobody yells “fire” to launch torpedoes on a U-boat. That would cause panic among the forty-odd men jammed in the tiny space because it meant the ship was ablaze. Instead, the captain, or more likely the first watch officer, would shout “torpedoes los,” meaning “torpedoes away.”

***

There are two periscopes on a U-boat. The one you see in most movies is the “observation periscope,” which is the one that goes up and down in the control room. It is primarily used to look for aircraft or threatening ships, not for firing torpedoes. That is typically done with the “attack periscope” operated above the control room and below the conning tower hatch. The captain, or first watch officer, sits on a metal bicycle-type seat and grips handles on either side, controlling the height of the periscope’s extension and its field of view; it does not go up and down. He uses pedals to rotate the periscope.

***

U-boats have two bathrooms, or “heads,” for the forty-plus men to use. But at the beginning of each voyage, one is jammed full of cans of food. So, when the line is too long for the remaining toilet or the ship submerges too deeply to flush because of outside water pressure, the sailors have only one option: buckets. They were usually kept on the floor in the diesel engine room and emptied after the U-boat surfaced. Just one more contributor to the odious brew of diesel fumes, body odor, moldy food, cooking, chlorine gas from damaged and wet batteries, and Kolibri, the sickeningly sweet-smelling cologne and deodorant sailors used in a vain attempt to cover body odor and to scrub off the saltwater encrusted on their faces.

***

Now to the mystery that took me the longest to solve: the steering wheel. I finally found one in the aft torpedo room that retracts to the ceiling. Turns out it was only used in emergencies. U-boats were normally steered electronically and not, surprisingly, by the chief helmsman, who was usually called Stürkorl, using Old German for helmsman. He oversaw navigation. During battle, the combat helmsman sat on a narrow wooden slat in the cramped conning tower and controlled the rudders by pushing one of two buttons on a box the size of a toaster. When submerged and not at battle stations, the helmsman on duty sat at the end of an L-shaped leatherette-covered bench where he operated a similar rudder control station on the forward wall of the control room while keeping an eye on the Hauptruder, a direction gauge for the main rudder; during docking, he manned a station on the bridge.

And now you know the rest of the story.

John Winn Miller

John Winn Miller is an award-winning investigative reporter (Pulitzer finalist), foreign correspondent, editor, newspaper publisher, screenwriter, movie producer, and novelist. The Lexington, KY native also produced four indie films, including Band of Robbers. He has taught Media Literacy classes at his alma mater, the University of Kentucky, and Transylvania University. He is also a second-degree black belt in Shaolin karate. Miller and his wife, Margo, live in Lexington with two standard poodles and a Maine coon cat. Their daughter, Allison Miller, is an actress-screenwriter-director currently starring in the ABC series A Million Little Things.

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

Next Blog: The Bravest Traitor

★ Learn More About Today’s Topics ★

Thank you to John for providing this list of recommended reading.

Blair, Clay. 1998. Hitler’s U-Boat War: The Hunted: 1942-1945. New York, NY: Random House.

—. 2010. Hitler’s U-Boat War: The Hunters 1939-42 (Modern Library War Book 1). New York: Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Brady, Tim. 2021. Three Ordinary Girls: The Remarkable Story of Three Dutch Teenagers Who Became Spies, Saboteurs, Nazi Assassins–and WWII Heroes. New York NY: Citadel Press. Kindle Edition.

Busch, Harald. 1955. U-boats at War: German Submarines in Action 1939-1945. New York: Ballantine Books.

Coder, Barbara J. 2000. Q-Ships of the Great War. Graduate paper, Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press .

Duffy, James P. 2001. Hitler’s Secret Pirate Fleet: The Deadliest Ships of World War II. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers,. Kindle Edition.

Goebeler, Hans, and John Vanzo. 2008. Steel Boat Iron Hearts: A U-boat Crewman’s Life Aboard U-505. New York:: Savas Beatie. Kindle Edition.

Liempt, Ad van. 2005. Hitler’s Bounty Hunters: The Betrayal of the Jews. Oxford, UK: Berg.

Miller, John Winn. The Hunt for the Peggy C: A World War II Maritime Thriller. Baltimore, MD: Bancroft Press, 2022.

Mulligan, Timothy. 1999. Neither Sharks Nor Wolves . . Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. Kindle Edition.

Rust, Eric C. 2020. U-boat Commander Oskar Kusch: Anatomy of a Nazi-Era Betrayal and Judicial Murder (Studies in Naval History and Sea Power). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

Woodman, Richard. 2011. The Real Cruel Sea: The Merchant Navy in the Battle of the Atlantic, 1939–1943. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, United Kingdom: Pen & Sword Books. Kindle Edition.

Deutsches U-Boot Museum. Click here to visit the museum web-site.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

I’d like to thank John for taking the time to contribute to this blog. I hope all of you enjoyed it as much as I have. As I previously mentioned, John is a meticulous researcher and when you read his new book, you will see how his research adds so much value to the cat-and-mouse storyline.

Winter is fast approaching, and you’ll likely be putting wood in the fireplace for evening fires. I can’t think of a better book than The Hunt for the Peggy C to read while sitting next to that warm fire. Click here to buy John’s book.

Sandy and I wish all of you a very Merry 🎅🏻 🤶 Christmas and a Happy ✡️ Hanukkah!

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Mark T. for contacting us regarding the blog, Camp King (click here to read the blog). Mark told us he grew up at Camp King while his father worked there. I’m sure Mark has some very interesting stories.

One of our strongest supporters is our good friend, John W. Sandy and I appreciate John’s willingness to introduce our blog site to anyone he meets who has an interest in history. Thanks John!

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2022 Stew Ross

WOW! That was another great one. I learned a lot of things I never knew before too. I intend to order and read the book. I especially liked the photo of Mr. Miller and his family. Thanks, Stew. Happy Holidays.

Hi Greg; thanks for your comments regarding John’s guest blog. It was a good one. He has a second book as a followup to the “Peggy C” and is currently working on a third book in the trilogy. I’ll let him know to go to the blog to read your comments. Hope you and the family are enjoying this holiday season. Happy New Year in advance. STEW