Most of us have never experienced blatant discrimination because of the color of our skin. Every country can point to episodes in its past that are regrettable and if possible, its citizens would certainly jump at the chance to turn the clock back and try to undo the damage. For America, I think most of us would agree that slavery was our low point. Even after the Civil War and emancipation, the Jim Crow laws of the south (and let’s not totally exclude the north) prevented African-Americans from exercising their rights. Before the civil rights movement of the 1960s, entertainers such as Sammy Davis Jr., Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Nat King Cole were not allowed to stay in Las Vegas hotels (in other words, you can perform here—to segregated audiences—but you can’t stay here). Our story today is about an African-American entertainer who moved to Paris during the Jazz Age because her talents were recognized and appreciated by the French. The welcome mat was always out for her to stay at the hotel of her choice. By the end of her life, Josephine Baker was hailed not only as one of the world’s top entertainers but also a World War II French Resistance hero and one of the leaders of the American Civil Rights movement.

Meet Freda Josephine McDonald AKA Josephine Baker

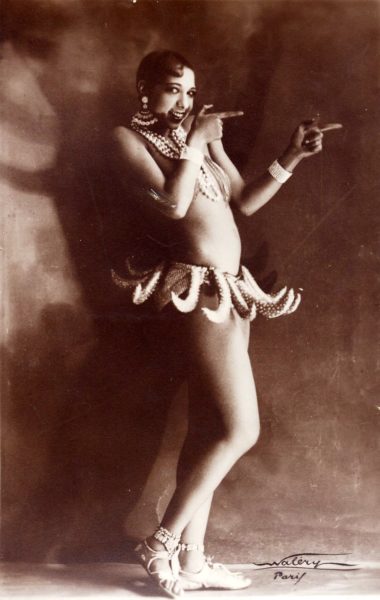

Josephine Baker (1906–1975) was born into extreme poverty in St. Louis. By the age of eight, her mother began to hire out Josephine as a live-in maid. One of her memories was being abused and punished if she made eye contact with her white employer. Five years later, Josephine was living on the streets and dancing on the street corners to make money (similar to the waifs in Paris—think Edith Piaf—who sang on the street corners in the early 1900s).

Josephine married the first of her four husbands when she was thirteen. At fifteen, she divorced him and married Willie Baker. Although divorcing Willie in 1925, she decided to keep his name as her audiences were beginning to recognize Josephine Baker as a top performer and dancer in the entertainment world.

Paris and Heartbreak

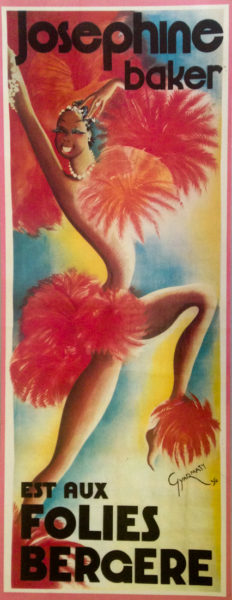

In part to get away from her mother, Josephine left for Paris in 1925 at the age of nineteen. The world was caught up in the Jazz Age and the Roaring Twenties. Four years later America (and soon the world) would enter the Depression era. In the meantime, Josephine quickly became a celebrity with the Parisians. Her first gig on 2 October 1925 was La Revue Nègre. She became known for her erotic dancing including appearing practically naked on stage wearing only the famous banana skirt. After a successful tour of Europe, Josephine returned to Paris where she began a long engagement at the Folies Bergère nightclub. She was the first African-American to star in a motion picture: Zou Zou (1934). By this time, Josephine had expanded her skills to include singing and comedy. Watch Josephine here.

Josephine returned to the United States in 1936 for the purpose of starring in the revival of the Ziegfeld Follies. Despite her success and popularity in France and Europe, American critics trashed her performance. This experience hurt her tremendously and when she returned to Paris in 1937, Josephine renounced her American citizenship and became a French citizen.

French Resistance Agent

Immediately after declaring war on Germany in September 1939, the French military organization known as the Deuxième Bureau recruited Josephine as an agent. Because she was a celebrity and had a need to travel, Josephine gained access to many embassy parties, rubbed shoulders with the highest military officers, and other assorted officials. She was able to learn about troop movements and locations, both of which she passed on to her handlers.

After the Germans invaded France and created the Occupied Zone, Josephine left Paris and moved to the south of France to live in her home, the Château des Milandes. Using this as her base, Josephine began to assist the French Resistance. Her celebrity status allowed her to move around Europe with relative ease. She began to assemble information concerning airfields, harbors, and German troop movements. Josephine would write her notes using invisible ink and hiding them in her sheet music. This information would then be transmitted back to London to Charles de Gaulle and the Free French.

Her work for the resistance movement was rewarded by giving Josephine the rank of lieutenant in the Free French Force. After the war, Josephine was awarded the Croix de guerre and the Rosette de la Résistance. In addition, General de Gaulle bestowed upon Josephine the prestigious Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur.

Back to the United States

After the war ended, Josephine returned to Paris and the Folies Bergère. Now, not only was she a top entertainer, Josephine was a recognized French war hero. At about this time, the French fashion industry was in disarray. Once they discovered another talent in Josephine, the top designers turned to her for help in designing the immediate post-war fashions. She is credited with saving the post-war Paris fashion industry.

Josephine was invited back to the United States in 1951. This time, she got great reviews and was given a wonderful parade in Harlem, New York. The NAACP honored her with the title “Woman of the Year.” Unfortunately, the warm and fuzzy reception was not to last.

She and her husband were refused reservations at 36 hotels in New York City due to her skin color. A night out at the famed Stork Club was the catalyst for her move back to Paris. She had been refused service at the club and she criticized their unwritten policy of discouraging African-American patrons (Grace Kelly witnessed this episode and came to her defense). After her friend Walter Winchell (soon to be ex-friend) refused to support her stand against the Stork Club, he began to write accusations that Josephine was a communist (remember, this was the McCarthy era—another sad episode in our history). This resulted in the cancellations of Josephine’s engagements and she returned to Paris once again, heartbroken.

It would be ten years before she would be invited back to the United States.

The Civil Rights Movement

Josephine experienced racism her entire life while living in America and on her subsequent returns. She refused to perform at any venue that required segregated audiences. Once while in Las Vegas, Josephine sat down on stage and refused to perform until the hotel permitted African-Americans to purchase tickets and attend her show. Josephine is credited today with helping to desegregate Las Vegas casinos (Frank Sinatra would refuse to perform anywhere unless the venue owners treated Sammy Davis Jr. as an equal).

Martin Luther King Jr. invited Josephine to be the only female speaker at the March on Washington in 1963 (she appeared in her French uniform). Josephine was given a life membership in the NAACP in recognition of her efforts. After Dr. King’s assassination, his widow, Coretta Scott King, reached out to Josephine and asked her to take over her late husband’s role as leader of the Civil Rights Movement. Josephine declined saying her twelve children were “too young to lose their mother.”

The Rainbow Tribe

Josephine never had any children of her own. She opted to adopt twelve children: two daughters and ten sons. The children were from France, Morocco, Korea, Japan, Colombia, Finland, Israel, Algeria, Ivory, and Venezuela. She called her children “The Rainbow Tribe.”

The children grew up at the Château des Milandes and accompanied their mother throughout Europe. Two of her sons, Jarry and Jean-Claude, went on to run a highly successful New York City restaurant called Chez Josephine. Appropriately, the restaurant is located on Theater Row and the décor highlights their mother’s career.

Josephine’s Legacy

Paris has honored Josephine’s legacy by naming the Place Joséphine Baker in the Montparnasse Quarter. A swimming pool located along the banks of the Seine in Paris is also named after her. The Château des Milandes is now open to the public and houses Josephine’s various stage garments (including the famous banana skirt) along with her medals and family photographs. Angelina Jolie has said that Josephine was her role model for the “multiracial, multinational family.”

Josephine lost her French home due to unpaid debts. Her friend, Princess Grace (Kelly), gave Josephine an apartment in Monaco. On 8 April 1975 in Paris, Josephine starred in a revue based on her 50-years in entertainment. Anyone who was anybody attended. Four days later, Josephine died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital and was buried in Monaco.

Le Monocle Nightclub

Josephine’s sons have written their mother was bisexual. During the 1920s and 1930s, a lesbian nightclub called Le Monocle was popular in the Left Bank of Paris. I’ve included an image of Josephine sitting in a racecar with Violette Morris. Violette was one of the more infamous patrons of the nightclub. As my recent blog pointed out, Violette was a notorious Nazi collaborator. So, I wonder if Josephine met Violette at Le Monocle and I thought it ironic that the two women were sitting side by side in this car—one a future Nazi collaborator and the other a future French Resistance agent.

African-American Ex-Pats in Paris

Josephine Baker was not the only African-American ex-pat performer in Paris—only the most famous. There were many African-American performers who moved to Paris between the two world wars. Although each probably had their individual reasons, the common thread was escaping America’s racism and Jim Crow.

The hub of activity for the African-American performers was the nightclub Chez Bricktop. Ada Smith (1894-1984) aka Bricktop opened the nightclub in 1924 and over the next forty years, owned and operated similar clubs in Mexico and Rome. A performer herself, Ada continued to perform well into her eighties. Watch Ada.

Chez Bricktop hosted celebrities such as Cole Porter (he hired Ada to entertain at his parties as well as financed the start of the club), the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, among others. During this time, Ada would mentor Josephine Baker (her sons wrote the two had a relationship together in the early days), Duke Ellington, and Mabel Mercer. Cole Porter’s song “Miss Otis Regrets” was written specifically for Ada. I hope you enjoy this 1934 rendition by Ethel Waters. I also happen to like the version by Bryan Ferry.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

I’m diligently working with image repository companies around the world to find interesting and relevant photographs taken during the German occupation of Paris. My primary sources seem to be The Image Works (the American distribution firm for Roger-Viollet), Alamy, Mary Evans, National Archives, Bridgeman Art Library, and the Bundesarchiv-Bildarchiv (the German Federal Archives). There are two primary issues with locating acceptable images: resolution and subject matter.

The images from the 1940s are low resolution. While this is fine for blogs that require only smaller pictures, it can pose a challenge when it’s time to put them in a book. Second, the subject matter was controlled by the Germans during the Occupation. The only photographs allowed were ones taken by the soldiers or an authorized photographer. If a civilian was caught with a camera taking photos, they would likely be shot. It was automatically assumed they were a spy.

Someone is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thank you to Jeanne C. for her comments concerning some spelling errors she caught in several of our blogs. We always appreciate feedback. We try and catch these errors but sometimes they slip through the editing net. Once someone like Jeanne brings it to our attention, we go back and correct the blog.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2017 Stew Ross