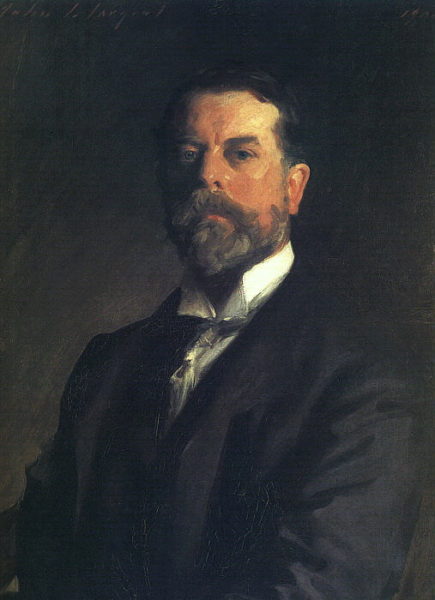

One of my favorite artists is John Singer Sargent (1856−1925). He was considered one of the leading portrait painters of his generation albeit as a “society artist” which some critics used in a derogatory manner towards him. Despite his American citizenship, Sargent lived abroad his entire life and became fluent in many languages, including speaking French without an accent. He trained under Carolus-Duran and passed the rigorous, one-month exam to gain admission to the prestigious art school in Paris, the École des Beaux-Arts. At the age of 21, Sargent’s paintings were first accepted into the Paris Salon and his career was launched as a portrait artist.

While this blog isn’t all about John Singer Sargent, his story intertwines tightly with the story of Virgnie Amélie Avegno Gautreau or Madame X as she infamously became known to Paris society. She would become Sargent’s most famous model and his most controversial. Her portrait created an immense scandal in Paris society and the art world in 1884. Whereas the scandal would engulf both the artist and the model, the artist’s reputation would eventually recover but the same could not be said for Madame X.

DID YOU KNOW?

Most of us know that adultery was an accepted behavior in France among the nobility (both sides were equally guilty) but as long as it was kept quiet, there would be no reason for alarm or at worst, a scandal. Marriages back then were arranged for political or economic reasons. Love never really played a part in the decision-making process (this probably was a major reason behind this behavior—not to mention boredom of the rich). There were definite periods of time when debauchery reached its zenith in French society (e.g., during the reign of King Louis XV and the Second Empire of Napoléon III). However, by 1871, the Third Republic was formed and henceforth, the nobility would be pushed aside in favor of the bourgeoisie (this is commonly known as the beginning of the Belle Époque period or perhaps maybe the French were beginning to reject the Victorian era morals and disciplines). Yet this concept of taking on a paramour did not subside as the status of nobility declined (it never really caught on too well with the working class or proletariat—husband and wife had to work for a living and they were typically equals in marriage and work). Society women would normally change wardrobes anywhere from four to five times a day depending on the event (e.g., lunch, afternoon tea, dinner, after dinner drinks, and midnight buffets). One event which forced women’s fashions to evolve was the “four-to-five.” This was considered the appropriate hour for infidelity. It was widely accepted the rendezvous would take place during this hour. Women were dressed in hoops, bustles, corsets, and petticoats making it difficult to arrange themselves quickly after their activities were finished. Some men would provide their lady friends with hairdressers and maids to assist them afterwards. One fashion change was the replacement of ribbons with hooks on the corsets. In the morning, the woman’s husband would tie her bows on the corset and then in the evening, he would notice the bows were tied differently. Hooks began to be used to disguise the evidence of her infidelity. Before too long, those testy garments were discarded in favor of loosely fitting gowns. As we say when looking for a fast food place or gas station on the interstate, “it has to be easy off, easy on.”

Let’s Meet Amélie

Virginie Amélie Avegno (1859−1915), born in New Orleans, was of noble French Creole descent. Her grandmother (Virginie Ternant) owned a rather large plantation—and its 147 slaves—called Ternant (later changed to Parlange) where Amélie would spend her summers (she never used Virginie as her first name). At the time, the Ternant family was likely the largest land owner in the New Orleans area. The family also maintained a residence in Paris located at 45, rue Luxembourg (the street name was later changed to Rue Cambon by Baron Haussmann).

When the Civil War began, Amélie’s father volunteered to serve in the Confederate army. Commanding a battalion named the “Avegno Zouaves,” Anatole Avegno was killed at the age of 26 during the Battle of Shilo. When the war ended, life in New Orleans was difficult for his widow, Marie Virginie de Ternant Avegno. In 1867, Marie Virginie and eight-year-old Amélie sailed for France and Paris where they would begin their new lives. All of Marie Virginie’s future attention would be on her daughter with only one goal in mind: getting Amélie tutored properly to enter Parisian society and find a rich husband.

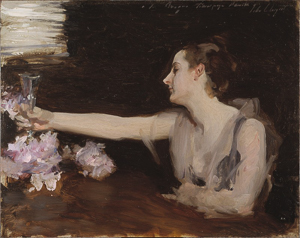

From a very young age, Amélie was a show stopper. Her father had pale skin, unusual copper-colored hair, and the distinctive “Avegno nose,” long, sharp, and Romanesque. Amélie inherited all three traits. Additionally, as she aged from adolescence to a young woman, Amélie developed a very beautiful physical appearance with curves, ample bosom, and a narrow waist. Her neck was long (described as almost swan like) and her shoulders elegant. Her pure white skin gave the appearance of sculpted marble. Her appearance was very classical and extremely attractive to potential suitors and artists such as John Singer Sargent.

Amélie was introduced by her mother into Parisian society as a teenager using diverse contacts within the government, entertainment world, and family connections. Even at this young age, Amélie knew what the rules were, what the game was all about, and what the end-game was supposed to look like. Finally, the “end-game” showed up. His name was Pierre-Louis Gautreau and he was more than twice Amélie’s age. But it didn’t matter because Gautreau was extremely wealthy.

Amélie and Pedro (Gautreau’s nickname) married: she was nineteen and he, forty. For Pedro, it meant he could finally move out of his overbearing mother’s house. For Amélie, it meant she was now Madame Gautreau and would be readily accepted into society. It also meant she was now respectable and could “loosen up” a bit.

A Fast Start For Artist and Model

The early 1870s in France saw a new crop of painters who began to paint in a way that contradicted the established and normal styles accepted by both society and the juried exhibitions. While this new movement had not been named yet, the term “Impressionist” would soon attach itself to artists such as Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, Degas, Manet, and others. The new style of “plein air” painting took the artist out of their studio into nature. Light, form, and perspective became their calling card. Sargent knew them all and he had studied under Carolus-Duran who embraced inventive painting techniques. Both Sargent and Carolus-Duran were able to exist in the “old world” and the new one. Most significantly, both of them were good businessmen and knew what style of paintings would attract critical acclaim, honors, and premium commissions.

The Paris Salon was the signature event for artists and the art world. It opened every May 1st and ran for six to eight weeks when hundreds of thousands of patrons would attend. Thousands of paintings were submitted for the honor of hanging in one of the thirty-one salles, or rooms—women were allowed to exhibit (in contrast to their exclusion from admittance to the École des Beaux-Arts). For the 1877 exhibition, Sargent’s first (at the age of twenty-one and unknown), he submitted the Portrait of Frances Sherborne Ridley Watts. The painting was accepted and placed in an advantageous location. Sargent was no longer unknown to the Paris art world.

Selection of Sargent’s annual submissions became a given. The 1879 exhibition saw him submit the painting of his teacher and mentor, Portrait of Carolus-Duran. The painting won honorable mention and Sargent gained an automatic selection for the 1880 show. Eventually, Sargent’s cumulative honors allowed him automatic acceptance in all future salons (I guess that’s sort of like winning the Masters golf tournament—you win and they let you come back every year).

The annual Salons provided Amélie with a different motivation—to be seen. She was never shy about her entrance as everyone in Paris knew about her legendary physical appearance. For Amélie, the paintings were a mere distraction to what she considered the real show—giving her admirers the opportunity to worship her.

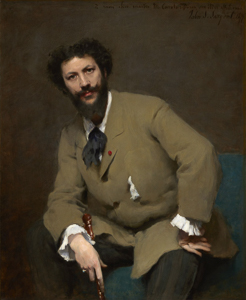

Sargent became distracted when he met Amélie while painting her lover, Dr. Samuel-Jean Pozzi, the well-known and respected gynecologist and surgeon. Sargent needed a spectacular subject for his next salon in 1884. Who better than the famous “Madame X” as the media was portraying Dr. Pozzi’s mistress (she was also known to be in the company of Ferdinand de Lesseps—read blog here). Amélie also needed a spectacular event to increase her public exposure.

The 1884 Paris Salon Submission

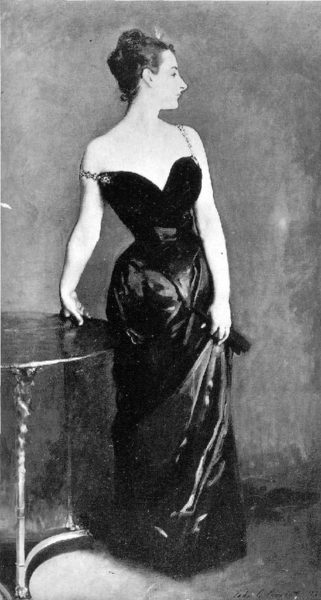

Pushing the envelope with his submission to the 1884 Paris Salon meant Sargent’s painting had to stand out from all the other great paintings. This would ensure an endless stream of commission requests and he could command a higher price. Here is a great example of “be careful what you wish for.” The artist began his pursuit of a new model: the twenty-four-year-old high society woman, Mme. Gautreau. His infatuation with her appearance would result in a painting that offended the jury, the critics, the patrons, and entire art world.

Sargent began to pursue twenty-four-year-old Amélie in early 1883 and it took him only two months to have her agree to sit for him. Sargent controlled every aspect of the portrait process. He decided to dress her in a stunning but simple black dress which accentuated her perfect figure. Posing her to reflect the profile of her head (and her well-known nose), Sargent decided to have the strap of her gown dangle down the right shoulder. This gave the appearance that the upper portion of the dress might fall down at any moment exposing her breast—this was not the case as the dress designer made the upper section structurally stable—in other words, there could not be a wardrobe malfunction.

Nevertheless, the pose was seductive and Sargent titled it, Portrait de Mme *** as if this would protect the identity of Madame X.

The Salon Disaster and the “Nowhere Man”

The result was reminiscent of the affaire de scandale when Édouard Manet exhibited his painting, Olympia, of a fully reclining, nude woman attended to by an African servant. While art critics and the general public enjoyed viewing paintings of nude women, the subjects were cloaked in classical, biblical, and generally historical themes (Eve, Lady Godiva, and playful nymphes were okay). Manet’s model was none of these—she was a “modern” woman. She was Victorine Meurent, one of Manet’s favorite models (and an accomplished artist in her own right). Manet portrayed her as a modern-day courtesan. While courtesans were accepted by French culture and into their society, having one displayed at the prestigious salon was unforgiving. Although the insults to Manet were fast and furious, his painting was the talk of the town for years. His reputation and livelihood ultimately survived.

While Amélie was not a courtesan, she was a contemporary, well-known socialite whom the artist had posed in a very seductive, and to viewers, erotic pose—it was suggested that Madame X was not wearing any undergarments since the dress clung to her body. As the critics, observers, and world press piled on, Sargent went to the judges of the Salon and requested to pull the painting so that a strap could be painted on her shoulder in the hope this would quell any criticism. The judges and other artists were appalled. A request to remove a painting during a prestigious exhibition like the Paris Salon had never been received and the artist was refused.

To make matters worse, Amélie and her mother, immediately cornered Sargent in his studio one evening. Marie Virginie demanded Sargent withdraw the painting from the exhibition immediately. While Amélie was blubbering in tears, her mother threatened Sargent with a duel—naturally, she would have someone else do the fighting. Sargent pointed out to his former model and her mother that they had enthusiastically supported the piece from inception to its submission. He refused to withdraw the portrait.

One of the effects of the disaster is that Amélie’s husband refused to purchase the painting—certainly an understandable emotional decision but as we’ll see in a moment, a poor economic one. So, after the show was over, Sargent collected his painting and brought it back to his studio on Boulevard Berthier. He proceeded to scrape off the fallen strap and repaint one on her right shoulder. Immediately, Madame X was no longer as seductive as she once had been and it would be years before the public would gaze upon her again.

Despite Sargent’s earlier success in the Paris Salon exhibitions, he was never accepted by the French. Everyone considered him to be very continental, debonair, and socially acceptable. But the one thing he couldn’t change was that he was American—he wasn’t French. The British never fully accepted him either because they felt he was “too French.” Talk about being caught between a rock and a hard place! He was truly a “Nowhere Man” and it cost him commissions.

Redemption

Almost immediately after the disaster, Sargent took off for London where he cavorted with his friends in the intellectual, literary, and art worlds. He continued to paint but requests for commissioned paintings dried up as potential patrons were scared of how he would present them. He left for the Cotswolds and the small village of Broadway where he was introduced to the Millet family and their children. Sargent became acquainted with Kate Millet’s friends, the Barnard girls. Over a period of three years, Sargent painted the two Barnard children in the enchanting garden of the Millets while holding glowing lanterns. He would only paint at the twilight so as to capture the light of late afternoon transcending into evening. The painting, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, was exhibited at the 1887 London Royal Academy of Art where it was a smashing success and enabled Sargent to restore his reputation and return to the upper atmosphere of artists. More importantly, commissioned requests began to materialize again.

Sargent’s international success was enough for the French to invite him to serve on the jury for the 1889 Salon. Unfortunately, for Mme. Gautreau, she did not enjoy the type of redemption the artist experienced. She was doomed to purgatory.

Amélie’s Post Salon Years

Amélie was used to being admired to the point of being idolized. She had a very difficult time accepting the less than flattering comments thrown at her in writing and verbally. Although she never stopped attending the important society events, Amélie did curtail her social calendar. Now, her entrance and presence never quite commanded the attention it once did and she knew it—in other words, Amélie wasn’t the show stopper she once was. But Amélie had another problem which clothes and make-up couldn’t fix: time was catching up to her and her figure.

They say time heals everything. Well, in this case it’s true, at least for Sargent. Over the years, the painting received its second chance. Sargent began to take it out of hiding and show it off. Critics claimed the painting to be a masterpiece (was this because the strap of the gown had been painted on her shoulder?). Eventually, Sargent lent his painting to major exhibitions around the world—I’m sure Amélie was kicking herself at that point for not having purchased the painting.

Amélie saw what was happening and determined that a solution for her “public relations” problem was to have another painting done but more flattering than Madame X. So, she commissioned Gustave Courtois to paint her portrait. This time, Amélie controlled all of the artistic phases including the pose and dress. She specifically had the artist paint the strap of her dress hanging down off her left shoulder. Was this on purpose as a comment about her former portrait and its artist? Despite her original disappointment, I think she might have had a great sense of humor in this regard. Anyway, the painting was exhibited and everyone yawned, including the critics. Other portraits would be painted but she never accomplished what she set out to do and Father Time continued to advance.

Amélie and Pedro had a loveless marriage and eventually separated. She moved to a smaller apartment near the Eiffel Tower in an area less toney than her previous residence on the fashionable Rue Jouffroy. She virtually cut herself off from society and friends. Amélie had all the mirrors removed from the apartment so she didn’t have to watch her appearance change. She never attended her daughter’s wedding. Eventually, Amélie’s mother and daughter, Louise, died within twelve-months of one another and now Amélie was completely alone and a committed recluse.

No cause of death was ever determined after Amélie died at the age of fifty-six in Paris. She died virtually alone with no friends. In her mind, the one and only asset she possessed had been slowly taken away from her and she could never regain it. M. Gautreau and John Singer Sargent outlived Amélie, the wife and model, respectively. She was buried in the Gautreau family mausoleum near the Pedro’s châlet, Les Chênes, located in the commune of Saint-Malo on the north coast of Brittany. It was here at Les Chênes that Sargent spent the summer of 1883 painting and sketching Amélie for his breakthrough painting, Portrait de Mme. ***.

Years ago, many people were curious why George Hamilton was so famous. The answer was always, “Because he’s a celebrity and has a perpetual tan.” We can ask the same question about Amélie. She was famous in her time because she was a celebrity. Her entrance to a venue and mere presence caused everyone to stop talking and stare at her beauty. When time began to ravage her only advantage, Amélie had nothing left. She didn’t even have the painting to replace her mirrors.

Recommended Reading

Davis, Deborah. Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 2004.

Horne, Alistair. Seven Ages of Paris. New York: Vintage Books, 2002.

McAuliffe, Mary. Dawn of the Belle Epoque. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2011.

McCullough, David. The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011.

I very much enjoyed Ms. Davis’s book. It was an easy and enjoyable read. She kept my attention throughout. I normally read four or five books at one time. I read this one from start to finish so that gives you some idea of how much I enjoyed it—sort of like reading David McCullough’s books.

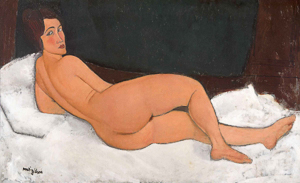

One last thing. Did you see the recent auction where Amedeo Modigliani’s painting of a reclining nude went for $157.2 million? I thought I’d bring this up because this is another example of a scandal created by a painting of a nude contemporary model. Modigliani painted a series of twenty-two nudes in just about every pose possible. These paintings, including Nu Couché (sur le côté gauche), were displayed at a Paris gallery in the early 20th-century. That is, until the French police shut down the gallery for indecency. Frankly, for all the amorous activity by the French nobility and bourgeoisie during the late afternoons, it certainly seems hypocritical of them to denounce the paintings we’ve mentioned in this blog.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

We just returned from New York where we spent four nights in Cooperstown. The purpose was to experience the Baseball Hall of Fame (HOF). We found out the HOF was founded by an heir to the Singer sewing machine fortune and continues to be privately owned and operated by the Clark family (Edward Clark was I.M. Singer’s partner and intellectual attorney when they founded the Singer Company). His descendants became huge art collectors and some of the pieces I ran across during my research for this blog hang in their museums.

We stayed at The White House Inn, within walking distance to downtown and the HOF (it’s really a small village). I’m not really a big Bed & Breakfast type guy but I would stay here again if we were to visit. Ed and his wife own the inn while Joshua runs it. They are one of the few inns that the HOF turns to every year to provide a place to stay for the HOF inductee’s family. If you are ever in Cooperstown and need a place to stay, be sure to let Ed or Joshua know (www.thewhitehouseinn.com).

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

As I mention above, we flew to New York to visit the Baseball Hall of Fame located in Cooperstown. Our good friend Rhea Seddon contacted us after she learned we had just returned. It seems her husband, Robert “Hoot” Gibson was born in Cooperstown in 1946. Both Rhea and Hoot are former astronauts and veterans of many space shuttle missions. I suppose I should go into the Wikipedia article on Cooperstown and add Hoot to the list of the town’s famous former residents.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2018 Stew Ross

Stew,

Thanks for the fun, Intriguing story about Madame X. I love Sargent too and, of course, know the story of the painting. But I had not heard the extended story of what happened to Amelie. Keep it interesting! Love reading your blogs.

Best

Hi Habib;

Thanks for the comments. Glad I could add some value for you regarding Amelie’s story.

STEW