Saturday morning, 15 December 1894, was cold, wet, and gloomy in Paris but that didn’t stop the small crowd of protesters who had come to the gates of Père Lachaise Cemetery to jeer at the procession. The object of their disdain was the old man who died eight days earlier at the age of eighty-nine. Despite the dignitaries and their eloquent speeches about the deceased, the protesters couldn’t and wouldn’t forgive Monsieur de Lesseps for being responsible for the loss of their life savings. M. de Lesseps was considered a national hero until his last act when his reputation was ultimately destroyed.

Did You Know?

This is the first of a series of blogs on men and women you’ve likely never heard of. I’ve run across many interesting people over the years of doing research for the blogs and the books. From time-to-time I will introduce you to some of them. They will all have two things in common: first, each of them is buried in a Paris cemetery and second, each will have led an extremely interesting life with interesting stories to tell you about. These are the characters who will be included in my future book, Where Did They Bury Jim Morrison, the Lizard King? A Walking Tour of Curious Paris Cemeteries. The people you and I visit may not be every day household names but they will entertain you.

So, what does M. de Lesseps share with P.T. Barnum? As you know, Mr. Barnum was a celebrated American showman, businessman, and politician. He was an effective speaker, persuasive in his arguments, did not give up in the face of absurd odds, and affected everyone he came in contact with. This pretty much sums up M. de Lesseps.

Let’s Meet Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand de Lesseps (1805−1894) was born into a family whose roots could be traced back to 14th-century Spain. His father was in the French diplomatic service in Italy (Napoléon made him a count). Ferdinand was educated in Paris and eventually entered the diplomatic corps. While serving in Alexandria Egypt, Ferdinand read a book about the Ancient Suez Canal which intrigued him enough to later propose building a modern version. By 1837, he had returned to France and married the daughter of the prosecuting attorney at the court of Angers (the capital of the important Middle Ages and Renaissance province of Anjou). The couple had five children of whom the eldest was Charles Théodore.

By 1851, Ferdinand had retired from diplomatic service. During the years he was stationed in Egypt and due to family connections, Ferdinand became good friends with Said Pasha, the son of the viceroy of Egypt. Said Pasha succeeded his father in 1854 as the viceroy and Ferdinand saw his chance to promote the building of a canal between the Mediterranean and Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez. Within three months, the new viceroy of Egypt officially authorized M. de Lesseps to build the Suez Canal. M. de Lesseps, the former diplomat, was now an engineer.

The Suez Canal

Over the next two years, M. de Lesseps negotiated, modified, and finally won approval in 1856 for the official route of the canal: a straight line bisecting the Isthmus of Suez. Once he put on his blinders, it was full steam ahead. Opposition by the English and French governments was immense but M. de Lesseps wouldn’t allow any adversity to deter him. To M. de Lesseps it only meant he would have to sell someone else on the advantages of joining him. So, he went directly to the citizens of France (and the United States) and issued bonds which raised half the money he needed. The other half came from the Egyptian government.

By the end of 1858, M. de Lesseps had organized a corporation to hold stock in the new venture. The next ten years proved difficult due to the continued opposition of the English as they were concerned the French would ultimately control the shortest route to India. However, on 17 November 1869, the canal was officially opened. M. de Lesseps basked in the glory that was rightfully his.

Despite the animosities, opposition, and hurdles presented by the English government, M. de Lesseps allowed the English to take an ownership position in the canal after it was completed (England bought out Egypt’s ownership position). He saw this was the best course of action for his canal—it would likely increase the traffic through the canal. The original investors were delighted with the substantial returns they received.

A monumental statue of Ferdinand de Lesseps was erected at the entrance of the Suez Canal. It was positioned so that his outstretched hand pointed the way to the East and India. Today, the statue stands in the Port Fouad shipyard. I suspect Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser had it moved in the late 1950s shortly after nationalizing the canal in 1956.

The Panama Canal

The Suez Canal was such a success that M. de Lesseps decided to try one more canal. This time, the ending wouldn’t work out as well for him.

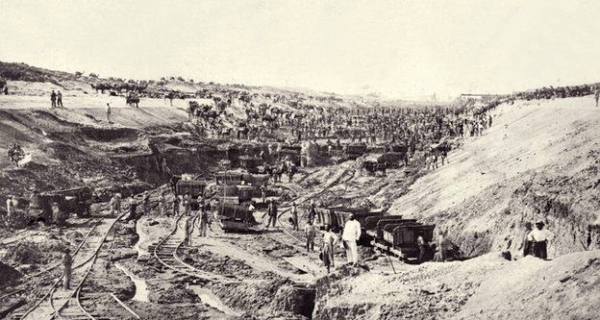

Ten years after the Suez Canal was opened, approval was given to build the Panama Canal and like the Suez Canal, it would have no locks—that would be the first problem. At the age of 73, M. de Lesseps was appointed president of the Panama Canal Company. He thought this project would be easy to accomplish since it was only 40% the length of the Suez Canal and by following the same game plan as building the Suez Canal, he could overcome any problems. Unfortunately, there were so many unique issues that the French efforts to build the Panama Canal resulted in failure.

The Suez Canal did not need locks as the two ends of the canal (Port Said at the Mediterranean and Port Tewfik at the Red Sea) and the land in-between were at the same elevation. The approved route of the Panama Canal differed in elevations and ships would need to be raised and lowered before emerging from the canal on either side. This presented an engineering challenge to M. de Lesseps who resisted putting in locks.

The canal was being built through a tropical rain forest whereas the Suez Canal was built in the desert. The dry season only lasted four months each year (M. de Lesseps visited the area only a couple of times and always during the dry season). The rainy season produced raging waters which could rise up thirty-five feet. The worst animal they encountered in the forest was the mosquito. The French were losing up to 200 workers per month from yellow fever and malaria.

They had to cut through mountains and found landslides to be a problem. Artificial lakes had to be dug out. Unfortunately, their heavy equipment rusted rapidly in the climate and had to be replaced.

M. de Lesseps now had a problem on his hands. Financial as well as completion targets were never met. Cost overruns began to sap the company’s finances. M. de Lesseps had no problem raising the initial capital based on his success with the Suez Canal. As the problems mounted, M. de Lesseps was forced to go out and raise additional capital which became increasingly difficult. However, by 1888, the Panama Canal Company went bankrupt and the following year began liquidation. The company had spent $287 million, lost more than 22,000 lives, and wiped out the savings of its investors, many of whom couldn’t afford to lose that kind of money.

The French involvement in building the Panama Canal came to an end on 15 May 1889. They abandoned all of their equipment and began to point fingers.

Disgrace

After the bankruptcy, the French maintained a minimal presence in Panama—just enough to fulfill their contractual responsibilities. In the meantime, they began to look for a buyer and M. de Lesseps was persuaded to accept a plan that included locks (as if that really mattered by then).

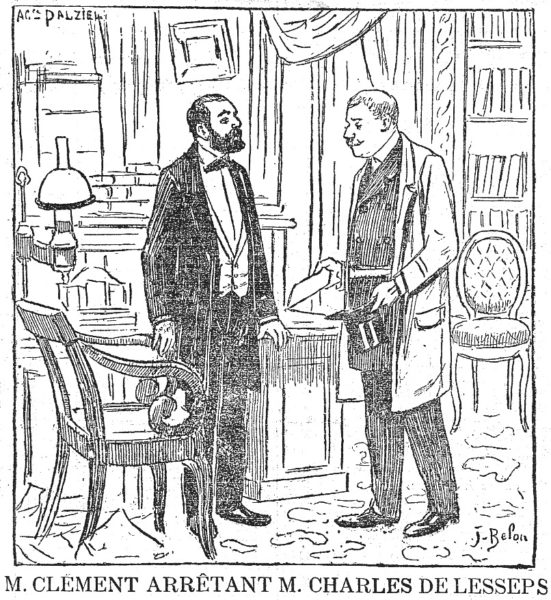

The ensuing “Panama Scandal” found that M. de Lesseps had bribed French authorities to vote for financial aid to the Panama Canal Company. In 1893, M. de Lesseps, his son Charles, and others (including Gustave Eiffel) went to trial. They were found guilty and M. de Lesseps was sentenced to five-years in prison and ordered to pay a fine. He did not serve time as the sentence was overturned on a technicality.

Postscript

With the support of the United States, Panama declared itself an independent country in 1903 (it had been part of Columbia) and President Theodore Roosevelt paid $10 million to the new government of Panama plus $250,000 per year for a renewable lease. He also authorized the purchase of French equipment and the Panama Railroad for $40 million (the original asking price had been $109 million). The Americans completed the construction and the Panama Canal opened on 15 August 1914 when the SS Ancon became the first ship to transit the canal.

I don’t know if Mr. Barnum really coined the term, “There’s a sucker born every minute.” But that small group of protesters outside Pére Lachaise Cemetery must have felt like it.

M. de Lesseps is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Division Six. His tomb is #40 as marked on the official cemetery map (you may purchase this for 2,00€ from a vendor outside the cemetery walls).

Recommended Reading

McCullough, David. The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870−1914.New York: Simon & Schuster, 1978.

Mr. McCullough is my favorite author who writes about historical events. His writing style is very fluid and easy to read even for people who aren’t into history. I read it before we took a cruise through the canal and I’m very glad I did. I highly recommend this book.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew

In addition to continuing to work on the new books Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? A Walking Tour of Nazi Occupied Paris, Sandy and I are compiling our list of interesting people to introduce you to in the book, Where Did They Bury Jim Morrison the Lizard King? A Walking Tour of Curious Paris Cemeteries. If you’re interested to know why they called Jim Morrison the “Lizard King,” read the blog here.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thank you to Richard K. for reaching out to us several weeks ago. Richard runs the Association l’Alliance in Paris, France. His organization is dedicated to preserving the memories of the brave men and women of the réseau Alliance (the Alliance Network). He is the grandson of one of the network’s leaders who was executed by the Nazis on 28 November 1944. Richard’s father was twenty when he fought the Nazis in Paris as part of the Forces Françaises de l’interieur (the FFI) while his mother provided aid and shelter to Allied downed airmen.

For those new to our blog site, “Stew Ross Discovers™,” we wrote about the réseau Alliance under our blog title Noah’s Ark. Read it here. I have a feeling that Richard’s organization is likely the definitive destination for anyone wanting to learn more about Alliance.

I hope you will visit their web site at www.reseaualliance.e-monsite.com. It is only in French despite the English version option. We’re going to work with Richard to try and get the French translated into English so all of us can read their stories.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2018 Stew Ross

I found a picture in an old book of M. de Lesseps (F) from 1887 with his second wife – “a young Creole lady of remarkable beauty” – and 9 of his 11 children by her. The caption notes that he was left a widower from his first wife at the age of 68 but doesn’t give the date of his second marriage.

Thank you Mr. Strachan for the update on M. de Lesseps. What was the name of the book you found the information in? If the book was printed in 1887, I would suspect he was still held in high esteem due to the successful building of the Suez Canal. STEW