Now do we really care how many times Mila Kunis bathes her children? Or for that matter, how many times Ashton Kutcher showers or the hygiene habits of any modern celebrity? (For our international friends, this has been a big topic of recent discussion on social media in our country.) I’m most concerned about the bathing habits of other people when I’m in Rome in mid-July on a hot and sticky day inside the Sistine Chapel packed with five thousand other people looking up at the ceiling.

I wrote a blog some time ago addressing medieval sleep habits (click here to read the blog, Medieval Sleep Number©️ Bed). The important question in that blog was “Why were beds so short back then?” It’s not what you might think but you’re probably close. So, today I believe we will discuss something most of us do after getting out of bed in the morning . . . namely, bathing habits. After the folks in the Middle Ages crawled out of their short beds, what was their daily hygiene process?

The answer as to whether people from the Middle Ages were, let’s say, aromatic is not clear cut. There are many opinions about bathing frequencies and types of bathing habits. Opinions are formed by studying medieval illustrations, written accounts, and pure conjecture. Some people believe bathing was done on a regular basis while others point to evidence supporting intermittent bathing. I have not run across anyone’s opinion that bathing was totally neglected. Like many historical questions, there is not one simple answer.

Did You Know?

Did you know that the French community of Illiers l’Évêque recently held a ceremony commemorating the crew of Stanley Booker’s Halifax bomber that went down near the town? Click here to watch the video. The ceremony also honored the seven airmen buried at Saint-André-de-l’Eure including Stan’s pilot, Sandy Murray, and W/O Taffy Williams. Stan and the other surviving downed airmen were taken in by some of the citizens of Illiers l’Évêque before making their way to Paris to join an evasion network. Unfortunately, Stan and others were betrayed and turned over to the Gestapo. His story is the subject of my blog, The Last Train Out of Paris (click here to read the blog).

Stan’s daughter, Pat, pulled together the ceremony and events with the help of Jean-Pierre Curato, a relative of one of the families that assisted Stan. It became an international event with representatives from the British, Canadian, and American embassies in attendance. The French military, local mayors, and community leaders also attended. Unfortunately, Pat and Stan were unable to make it, but they were well represented by several relatives along with retired air Commodore Barry Dickens and his wife.

Thank you to Pat for sharing the story of this event as well as the numerous images, videos, and other media coverage of the memorial ceremony.

I’d like to share it all with you, but I’ve chosen the following: Reception Click here to watch the reception.

Royal Air Force Article Click here to read the article.

Ceremony Click here to watch the ceremony part 1. Click here to watch the ceremony part 2.

Stanley Booker Interview Click here to watch the interview.

Middle Ages

The European Middle Ages are defined by three periods: Early (300−1000), High (1000−1300), and Late (1300−1500). (The term “Middle Ages” did not appear until the 15th-century.) The Early Middle Ages was previously referred to as the “Dark Ages” because few if any written records of that time have been discovered. Trust me, it was not “dark”⏤the sun came up every day. It is important to remember that there is a transitional period between the end of one historical era and the beginning of a new one. For example, historians commonly point to 500 A.D. as the end of the Roman Empire. In reality, the “end” was a decline over several centuries. So, even though the beginning of the Italian Renaissance supposedly signaled the end of the Late Middle Ages, there was no singular or fundamental break from the past. In other words, no one flipped a switch.

During the Early Middle Ages, medieval society was split into four parts: nobles, non-nobles, clergy, and non-Christians. During the High and Late Middle Ages, the working class and middle class were added to the non-noble classification. One of the key aspects impacting bathing and hygiene habits was the economic stratification of each class.

Bathhouses

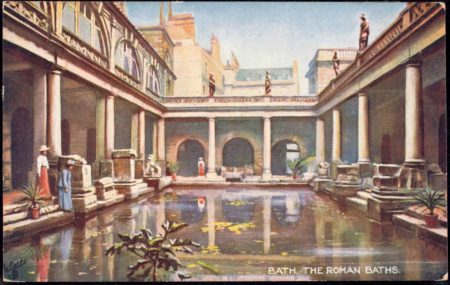

Before the Middle Ages, the Roman Empire ruled much of the continent. The Romans believed in bathing regularly and built public bathhouses throughout their conquered territories. Many of the baths have survived two thousand or more years and one of the most famous (and still functional) is in Bath, England. The ruins of Roman baths can be seen on the Left Bank of Paris as part of the Musée national du Moyen Âge, or the Cluny Museum (click here to read the blog, Paris History Museums). While soap was invented by the Babylonians around 2800 BC, it became widely popular during the last five hundred years of the Roman Empire.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire, public bathing declined but the knights of the crusades revived the popularity of bathing and many of the surviving Roman public baths were used as well as newly constructed bathhouses. In Paris, public bathing was such a big business that the keepers of the bathhouses formed a guild to establish rules and regulations to ensure the longevity of their businesses. (By 1292, there were more than thirty public bath facilities in Paris and eighteen in London.) Some of the Paris guild’s rules were as follows:

- No man or woman of the aforesaid trade may maintain in their houses or baths either prostitutes of the day or night, or lepers, or vagabonds, or other infamous people of the night.

- No man or woman may heat their baths on Sunday.

- Be it known that no man or woman may cry or have cried their baths until it is day, because of the danger which can threaten those who rise at the cry to go to the baths. (Huh?)

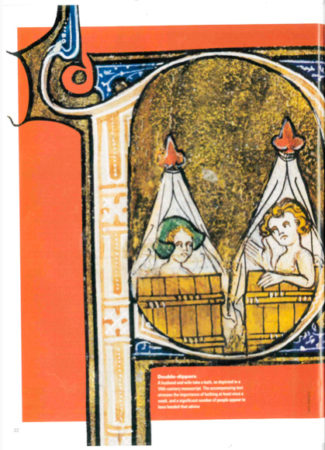

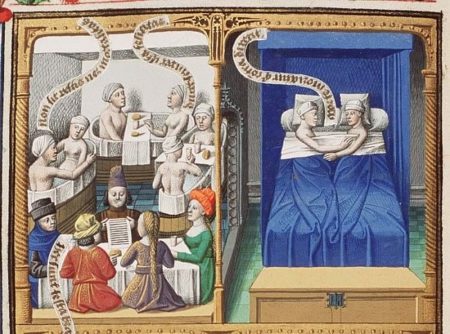

Now, in London, the public bathhouses were a place where not only could one get a regular bath but enjoy other earthly delights (if you get my drift). Although against the law, sex in the bathhouses was overlooked by the proprietors. The public facilities included steam baths, wooden tubs, and the opportunity to grab a bite to eat.

The early Christian church disapproved of communal bathing. Since it involved nudity, sexual freedoms had to be suppressed. (Bath water was heated and it was believed to inflame lust for the opposite sex.) Most of the monks and clergy saw washing as a sign of vanity and sexual corruption. Some monks only bathed twice a year (i.e., Christmas and Easter). That is, except for the monks of Westminster Abby who hired their personal bath attendant. In other words, the filthier you were, the humbler and more pious you could claim to be.

The number of European bathhouses began to decline in the 16th century. The Elizabethan era put a damper on bathing by declaring that cleaning oneself weakened the body while washing the skin left it more susceptible to infection. Pandemics represented another nail in the bathhouse coffin. Public bathing would not make a resurgence until the 18th century when spas became popular.

Social Status

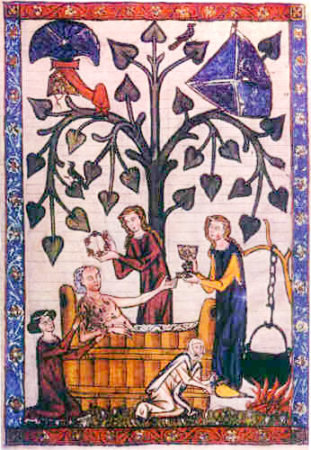

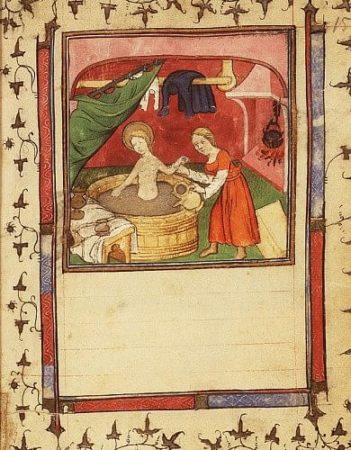

If you were wealthy, not only could you afford a private bathtub, but you could probably pay other people to fill it, wash you, and dry you off (and maybe other stuff). However, most medieval citizens were not wealthy. Almost ninety percent were peasants and most of these people worked as laborers in the fields. They tended to wash once a day by wiping themselves down. A ewer (i.e., pitcher or jug) was filled with water, heated, and then poured into a large basin. No water or heat? No problem. It was likely a short walk to a river, stream, or other local water source. Whether you were wealthy or a peasant, bathing was quite a chore. Common sense says the peasants probably didn’t bathe as often as the rich folks.

Yes, they used soap. But the wealthy also scented their bath water by throwing in herbs such as sage, rosemary, and thyme. (Simon and Garfunkel must have been fans of medieval bathing: click here to listen.) Deodorants were made from bay leaves, hyssop, or sage. Unfortunately, our medieval ancestors could not run down to the nearest Kroger, Carrefour, or Tesco to buy toilet paper. Their options were leaves, moss, a rag, or hay. If they were well-off, they could afford to wipe their bums with lamb wool. If you were king or queen, you employed the Royal Toilet Attendant. For the king, it was the “Groom of the Stool” or “Master of the Chamber” while the queen had her “Chief Gentlewoman.” As I’ve always said, “It is good to be king.” By the way, never jump into the moat that surrounds your castle. The plumbing system was designed to deposit all human waste into the waters of the moat. Refer to my blog, Thomas Crapper: Remembered from the Bowels of History (click here to read).

Bathing Habits of Celebrities

Reportedly, Queen Elizabeth I only bathed once a year. Queen Isabella of Castile beats that record. Reportedly, she only bathed twice during her lifetime: when she was born and the day she married Ferdinand of Aragon. On the other hand, Isabella’s daughter, Juana, was fanatical about bathing herself. Her husband thought she was killing herself by bathing and washing her hair so often. Although he was a bad king, King John wasn’t a dirty king. He travelled with the royal bathtub and his bath attendant. (King John may be remembered for having lost the English crown jewels but he never lost his bathtub.) After Thomas Becket was murdered, the monks found fleas and lice all over his body and clothes. It seems the archbishop of Canterbury never took a bath or washed. Becket was canonized and I heard somewhere that Kohler Co. adopted him as their patron saint. (Kohler makes bathtubs). While Napoléon I was not part of the Middle Ages, he ordered Josephine to stop bathing a week before he returned home from his military campaigns. (Hey, I don’t make this stuff up.)

My Conclusion

So, the question raised is whether the people of the Middle Ages took baths and how often did they wash? Some say the medieval people rarely bathed while others say most of them didn’t want to walk around stinking up the place. Who are we supposed to believe? Well, I decided to take the middle road. I have concluded that people bathed more often than the skeptics have postulated but not as much as those who believe it was a common occurrence. After “studying” many of the available illustrations, I am convinced washing up in the public bathhouses was quite enjoyable.

I found only one conclusion that every pundit and author agree upon: the medieval public bathhouses were an acceptable place to have sex.

★ Learn More About the Stinky Middle Ages ★

Handley, Sasha. Sleep in Early Modern England. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Newman, Paul B. Daily Life in the Middle Ages. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Co., 2001.

Roux, Simone. Translated by Jo Ann McNamara. Paris in the Middle Ages.

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009. Originally published as Paris au Moyen Âge by Hachette Littératures.

Singman, Jeffrey L. The Middle Ages: Everyday Life in Medieval Europe. New York: Sterling, 2013.

Smith, Virginia. Clean: A History of Personal Hygiene and Purity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Good news!

We have received the proof book from our printer. Final corrections have been made and Roy has sent the final file to Pollock Printing in Nashville. According to Alex Pollock, there has been a disruption in the supply of paper (so what else is new?). We use very good quality paper stock for our books, and I suspect there may be a delay in obtaining what we need. Unfortunately, it’s out of our control but we have our fingers crossed that there is enough time between now and the end of the year to get this book printed and available for purchase. Stay tuned.

I’d like to thank those who provided us with testimonials for the new book: Stanley Booker, Paul McCue, Richard Neave, and Dr. Cynthia Bisson.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Mitch S. for contacting us regarding our blog, The Wise Men (click here to read the blog). Mitch commented on McCloy’s “wanton disregard of all principals of accountability and justice . . .” Mitch, I couldn’t agree more.

I’d also like to thank Pat P. for introducing us to the story of Salon Kitty. He’s writing a novel using the story of this Berlin brothel. I did some preliminary research and I think there may be some fiction intermingled with fact. But it is such an interesting tale that I’ve decided to use the topic as our final blog in 2021.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please contact Stew directly for purchase of books, Kindle available on Amazon. Stew.ross@Yooperpublications.com or Contact Stew on the Home Page.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2021 Stew Ross

Very entertaining tale of soap and water and related non-hygienic sports. Great read. Thanks, Stew.

Thanks Greg! Good to hear from you. STEW