The longer one spends in Paris (or any city for that matter), certain questions ultimately arise over innocuous issues. Sandy and I are interested in the history of the City of Light and over time we notice little things that lead to more questions. For example, after multiple trips to Paris to research our first two books (Where Did They Put the Guillotine? Volumes 1 & 2 ), it occurred to me that there were no major statues commemorating the French Revolution or the revolutionaries (other than Danton’s statue or several located in the exterior alcoves of city hall). I found old postcards showing photos of statues dedicated to the revolution, but they are all gone now. Why? I found the answer while researching the current books on the German occupation of Paris (Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? ). During the occupation, the French melted down most of the bronze statues to provide ingots that were used to repay German reparations and cover the cost of the occupation forces. (Click here to read the blog, Statuemania.)

Today’s topic deals with a similar type of issue but I’m not sure I have found the answer to my question. During the mid-19th-century, Paris was “reborn” when it was transformed into a modern city by Emperor Napoléon III and his préfet, Baron Georges Haussmann. Over a period of 17-years, day and night demolition and construction created the city we all love today. The wide avenues, homogenous architecture known as Haussmann buildings, and beautiful parks are all sights we can identify with and enjoy. However, there are many other infrastructure improvements, some visible and some not, that Napoléon III was responsible for initiating.

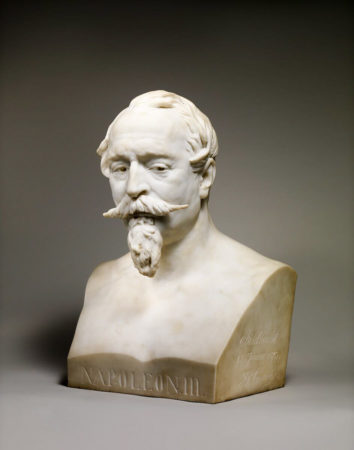

Considering the immense contributions by the emperor, I wonder why there are no memorials, statues, or commemorative plaques to Napoléon III. The city’s transformation did not come cheap. There were considerable costs with ramifications that can still be felt more than 170-years later. Have the French not forgiven Napoléon III for these negative costs or maybe perhaps, that he lost a war to the Prussians?

(This blog is based on my two-hour lecture, The Destruction and Renovation of Nineteenth Century Paris.)

Did you Know?

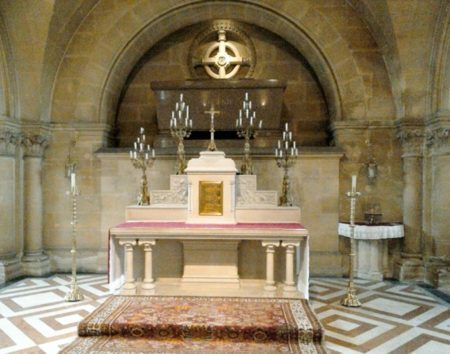

Did you know that Notre Dame is beginning to give up some of its secrets? During the recent efforts to save the cathedral after the devastating fire in April 2019, two lead sarcophaguses were discovered buried beneath the nave. One contains the remains of a high priest, Antoine de la Porte, who died on Christmas Eve 1710 at the age of eighty-three. The occupant of the second sarcophagus was likely a young, wealthy, and privileged noble from the 14th-century. (He was in his 30s and based on the pelvic bones, considered to be an expert horseman.)

Their remains were located about one meter (3.3 feet) below the cathedral floor. However, there were other items found at a lesser depth. These buried treasures included statues, sculptures, and fragments of the cathedral’s original 13th-century rood screen.

As I’ve said before, one of the world’s greatest museums lies twelve feet below the surface of Paris but the French do not take too kindly to people digging up their city. Archeological finds are normally found only when basements are renovated or associated with construction on métro stations. (Please note that the remains of the two men are not considered “archeological objects” and will be returned to the Paris cultural ministry for proper burial.) France’s national archeological institute, Inrap, is responsible for the dig at Notre Dame and the objects found there.

For additional reading, please refer to my past blogs, Stop the Presses: Skeletons and Not Buildings (click here) and Paris Digs (click here).

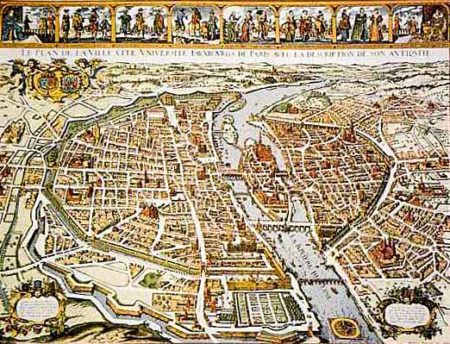

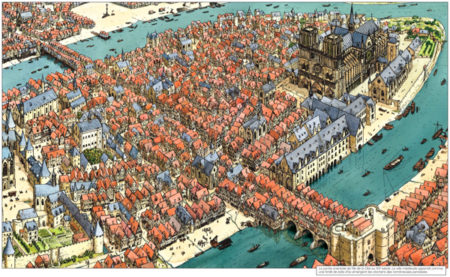

Medieval Paris

Founded in the 3rd-century by the Parisii tribe, Paris was originally settled by the Romans in 52 B.C. on what we call today, the Left Bank (the Right Bank was marshland). The city was then known as Lutetia. Other than an old arena, several remnants of the city’s Roman aqueduct system, and some odds and ends, there is no evidence of the Roman settlement. The two best sites in Paris to experience medieval life is to visit the Musée national du Moyen Âge Paris, or Musée de Cluny and the Crypte archéologique de l’île de la Cité, or the Archeological Crypt. (The Panthéon sits on the site of the ancient Roman forum.)

Beginning with the rulers of the Merovingian dynasty (e.g., Clovis I; c. 466−c. 511) through the Bourbon dynasty (e.g., Louis XIV, Louis XVI, and Charles X), the French kings resided in or near Paris. The first walls surrounding the city were built by Philippe II between 1190 and 1213 followed by Charles V’s wall built between 1356 and 1383 on the Right Bank. The kings lived in various palaces throughout the city’s history, some of which still exist in whole or portions.

The medieval period is generally defined by the Early Middle Ages (300 A.D.−1000 A.D.), High Middle Ages (1000 A.D.−1300 A.D.), and the Late Middle Ages (1300 A.D.−1500 A.D., or the beginning of the Renaissance period).

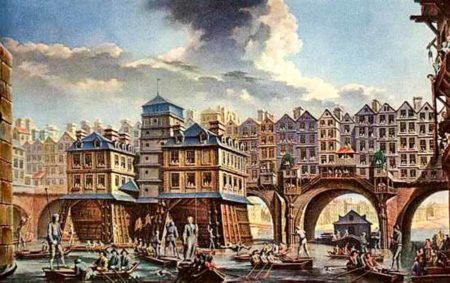

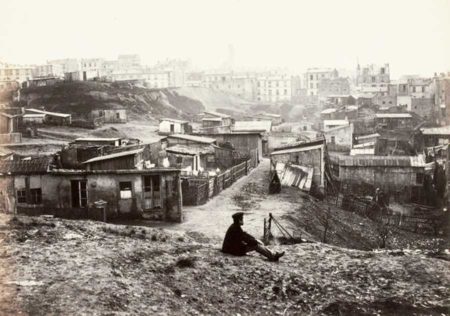

Medieval Paris was not a nice place to live. The city was filthy, smelled, had unsafe drinking water, chaotic traffic, an insufficient number of bridges, and above all, it was a dangerous place. (Click here to read the blog, The Stinky Middle Ages) Paris was overcrowded and unhealthy with a death rate of four of every seven infants born in the city. Disease spread rapidly and cholera was especially dangerous. There were no street signs, so it was easy to get lost (most people stayed in their neighborhoods). The streets were narrow, dark, and unsanitary (they were used as sewers). Only two parks existed for the enjoyment of the Parisians. The Seine was a depository for garbage, human waste, and dead bodies. Thieves, criminals, and murderers roamed the streets of Paris throughout the day and night. (Click here to read the blog, Cour des Miracles) However, the greatest number of deaths inside the city were caused by wild boars. The noise from the city was deafening. Written accounts by travelers indicate they could hear the sounds from miles away as they approached Paris.

Attempts to Modernize Paris

In my opinion, there were only a handful of kings who tried to improve living standards for their subjects: Philippe II Augustus (r. 1180−1223) built the first wall to protect Paris from invaders, Charles V (r. 1364−1380) is considered one of the greatest French kings, and Louis IX (r. 1226−1270) is the only French king to be canonized by the Roman Catholic Church (The U.S. city of St. Louis is named after Louis IX.) The first Bourbon king, Henri IV (r. 1589−1610), was perhaps the best monarch when it came to looking after the welfare of his subjects. He once said he would put “a chicken in everyone’s Sunday pot.”

Each of these monarchs contributed significant improvements to Paris and raising the standard of living for its citizens. During the First Empire (1804 to 1814), Napoléon I is also recognized for “modernizing” the city. He had five new bridges built, his administration addressed the issue concerning water quality, built new markets, and stopped the cattle from being herded through town. After Napoléon I abdicated on 22 June 1815, virtually all building and/or improvements stopped. During the thirty-three years between the restoration of the monarchy with Louis XVII and the establishment of the Second Republic in December 1848 with Prince Charles-Louis Napoléon as its president, the city came to a dead stop with respect to improvements. In fact, by 1840, the rich, the nobility, and bourgeois Parisians stopped going into the center of Paris.

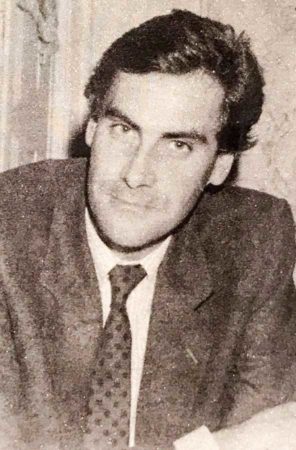

Let’s Meet Prince Charles-Louis Philippe Napoléon

Prince Charles-Louis Philippe Napoléon Bonaparte (1808−1873), commonly known as Louis Napoléon, was born to Louis Bonaparte (1778−1846) and Hortense de Beauharnais (1783−1837). Louis Bonaparte was the younger brother of Napoléon I and appointed king of Holland by his brother. Hortense was the only daughter of Josephine, Napoléon I’s first wife. (Josephine’s first husband and Hortense’s father was guillotined during the revolution.) So, Louis Napoléon was Napoléon I’s nephew and the emperor served as godfather to his nephew during the baptism at the Palace of Fontainebleau on 5 November 1810.

Louis Napoléon was exiled from France after the 1815 defeat of his uncle and the Bonaparte family moved to Germany where he was tutored by Philippe le Bas (1794−1860), the son of a prominent French Revolution leader. In 1836, Louis Napoléon landed in Strasbourg, France where he attempted unsuccessfully to overthrow King Louis-Philippe (the last Bourbon king and a member of the House of Orléans). After failing, he went back into exile and ended up in London.

Four years later, in 1840, Louis Napoléon attempted a second overthrow of the French monarch, and the result was the same. Only this time, he was captured, put on trial, and sentenced to life imprisonment in the Fort of Ham. Louis Napoléon escaped in 1846 and once again, fled to London. Over the next two or three years, he became quite the celebrity in London and enjoyed the social company of leading English politicians, society-type folks, and nobility. Louis Napoléon fell in love with London and its many “civilized” attributes (e.g., parks).

The French Second Republic

Between April and June 1848, Louis Napoléon returned to France for the purpose of running for the French National Assembly and remarkably, he got elected. But once again, they kicked him out of France and Louis Napoléon sailed back to . . . London.

In June 1848, an uprising in France forced Louis-Philippe to abdicate the French throne and the Second Republic was born. (The First Republic was formed during the French Revolution and dissolved when Napoléon I became emperor in 1804.) Louis Napoléon successfully petitioned the government to allow him to return to France and he took his seat in the National Assembly. He ran for president and gained the support of the media, celebrities such as Victor Hugo, and the general population (his name certainly didn’t hurt his chances). Remarkably, Louis Napoléon won the 1848 election with 74% of the votes and he saw that as a mandate to enact his vow to end poverty and improve the lives of normal citizens.

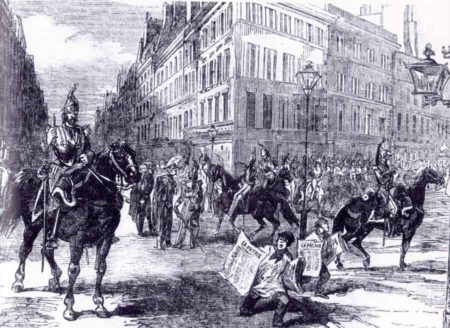

The Coup

French law prohibited consecutive terms of the presidency. Louis Napoléon tried to change the constitution but failed. Not content with being an authoritarian leader, he decides to become a dictator like his uncle. So, Louis Napoléon holds a big Christmas party in December 1851. Everyone who was anyone was invited. The army was on his side and while the city was empty (the rich and powerful were attending the party), Louis Napoléon overthrew the government thus ending the Second Republic. It took about a year for him to change the constitution and get re-elected to a ten-year term. The new term was window dressing as he ultimately declared himself emperor and established the Second Empire.

The Second Empire

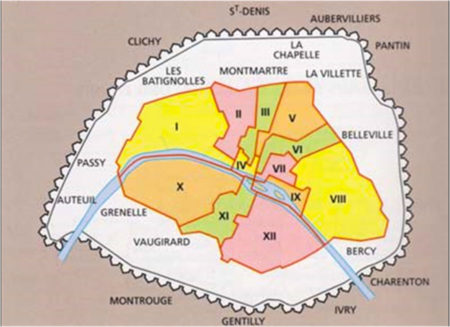

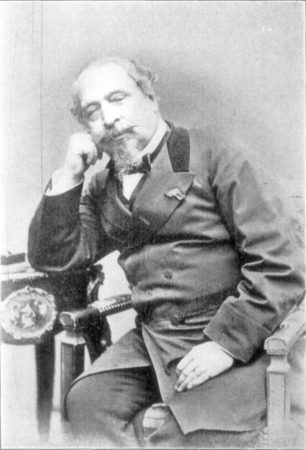

Holding all the power, Louis Napoléon declared himself the emperor in 1852 and proclaimed his plans for the massive “renovation of Paris.” One of his first acts as emperor was to fire Jean-Jacques Berger, the préfet of the Seine, and hire Georges-Eugéne Haussmann (1809−1891). Haussmann would serve the emperor as préfet of the Seine between 1853 and 1870. Every day for seventeen years, Napoléon III and Haussmann would meet in the morning at the emperor’s office to discuss the renovation project that became known as “The Colored Plan.” The emperor’s first instructions to his new préfet were, “Bring air, light, and open space to the city.”

I guess you can think of Napoléon III as the “architect” of the new city while Haussmann was his “contractor.”

The Colored Plan

Napoléon III was the driving force behind the restoration. He incorporated ideas from his experiences in London and approached the restoration from the standpoint of improving living standards for the Parisians. With the emperor’s vision and guidance, Haussmann was entrusted with carrying out the plan. Behind Napoléon III’s desk hanging on the wall was a huge map of Paris. The plan incorporated strategies for financing, eminent domain, new decrees, architectural, infrastructure improvements, and new streets. No city in Europe had ever been rebuilt while still intact. London, Rome, Copenhagen, and Lisbon were rebuilt only after a fire or earthquake had destroyed much of the city.

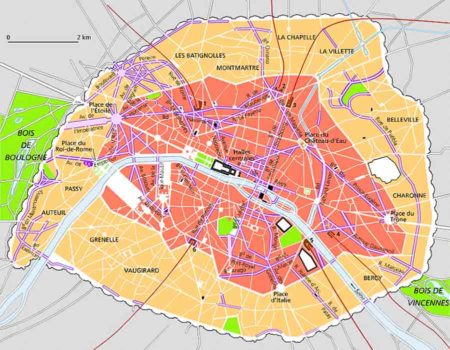

The project began in 1853 and ended in 1870. Demolition and construction continued day and night, seven days a week for the entire seventeen years. Beautiful avenues were created, Haussmannian style architecture was introduced, new arrondissements, or districts were established through annexation of suburbs, historic buildings were demolished, business and landowners became fabulously wealthy, poor people became even poorer, and hundreds of thousands of people were displaced and forced to move to the slums. However, during those seventeen years, Paris’s “medieval cloak” was gradually removed and replaced with a new and modern city.

The Four Major Goals

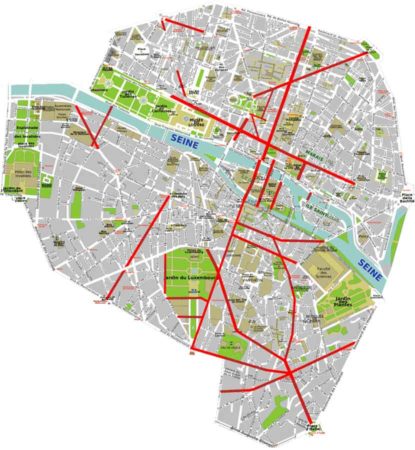

Napoléon III’s four major goals were to build new boulevards and widen existing ones, ensure the military (including the national guard) could move easily and quickly through the streets of Paris, create new parks and squares with the intent that everyone could walk to one within fifteen-minutes from their home, and finally, create the “Grand Cross of Paris” (i.e., intersecting east-west and north-south grand boulevards).

Construction Phases

The first phase between 1853 and 1859 created the grand cross. The north-south axis was bd de Strasbourg to bd Sébastopol to Pont-au-change to bd du Palais to bd Saint-Michel. The west-east axis was rue de Rivoli to rue Saint-Antoine to rue du Faubourg Saint-Antoine to place de la Nation. During this phase, rue de Rivoli was completed with its luxury retail stores. Many historic buildings were demolished during this time. Seven miles of new roads were constructed.

The second phase (1859 to 1867) concentrated on demolition, building the roundabout with twelve radiating avenues around the Arc de Triomphe, repairing Sainte-Chapelle and Notre-Dame (the spire was restored after its destruction during the revolution), Hôtel Dieu was moved and enlarged, Chaillot hill was leveled with its medieval village destroyed (where the Trocadéro now sits), Gare Saint-Lazare was built, and the Butte des Moulins, next to the Porte Saint-Honoré, was removed with the dirt hauled over to the Champ de Mars to level the giant field. Seventeen miles of new roads were constructed.

The third and final phase between 1867 and 1870 saw increasing criticism with most of it aimed at Haussmann. The public was getting tired of the day and night construction, the politicians were getting tired of continuously being asked for more money by Haussmann and finally, Napoléon’s wife, Eugénie, talked him into going to war. During these three years, the Place du Trône, or Place de la Nation was completed, the Paris Opera and ave. de l’Opéra were built, and the Champs-Élysées was redeveloped.

Significant Improvements

- A major effort was undertaken to design and build new parks and squares. In 1848, Paris had 47 acres of parks. By 1870, the city could boast it had 5,000 acres of parks. More than 600,000 trees were planted. Twenty-four neighborhood squares totaling about one million square feet were built. The goal of having a park or square within a fifteen-minute walk of everyone’s home was accomplished.

- Improved sanitation systems were developed including rebuilding the antiquated sewer and water systems. Water distribution went from 87,000 cubic meters per day to 400,000. Prior to 1855, only liquid waste could be handled by the Paris sewers but now, the new sewers could dispose of solid waste. For the first time, water was separated into potable and non-drinkable.

Underground Paris Construction. New water pipes and sewers built under blvd Sebastopol. - Three new rail stations were built: Gare de l’Est, Gare du Nord, and Gare Saint-Lazare.

- Improved traffic circulation was designed to save time and lives.

- Les Halles market was renovated.

- The remains of more than six million people were removed from city cemeteries and buried underground in the catacombs.

- More than 15,000 streetlights were installed by 1867. (Pre-1850, the city had 9,000 streetlights.)

- The plan created schools for girls and Napoléon III forced the Sorbonne to admit women. The first female university graduate occurred during the Second Empire.

- Approval to build the Suez Canal turned out to be a financial success for the French investors.

- Major social reforms were approved including giving workers the right to organize and strike. Many of Napoléon’s social reforms are still in place.

- Even little details such as new park benches, garden fences, kiosks, park shelters, and public toilets were not overlooked by the emperor and his préfet.

The Aftermath

Approximately 20,000 medieval buildings were demolished and replaced by 30,000 new buildings. Haussmann’s new buildings contained 215,300 apartments compared to the 120,000 apartments that were destroyed. Gentrification of the “old” neighborhoods forced residents to move to other areas of the city disrupting their lives. Slum areas in the north were created and still exist. (Low-income housing vanished and rents increased by 300%.) The population of Paris went from 400,000 (pre-construction) to 1.6 million people. (The population of Paris today is about 2.2 million.) Napoléon III doubled the footprint of Paris through the annexation of suburbs. (Citizens were not happy as their taxes increased and they lost their independence.) Excavations revealed may ancient archeological finds including the ruins of the Roman arena known as the “Arènes de Lutèce.”

Mounting criticism over cost-overruns, constant construction, displacement of hundreds of thousands of residents, and ensuing corruption forced Napoléon III to fire Haussmann in January 1870. The citizens of Paris wanted to take a break from building. They wanted to leave the next major building phase to subsequent generations and that is what happened. By the early 1920s, Napoléon III’s vision was finally completed. However, there was still work to be done. Parts of historic Paris (e.g., Village of St. Paul in the 4e) did not receive running water until 1971.

Where Do You Stand?

At the end of each lecture on this topic, I ask my audience to vote on whether they think the destruction and rebirth of Paris was worth the costs in terms of money, impact on human lives, and the legacies Paris is burdened with today. Was Napoléon III a master planner or megalomaniac focused on his legacy?

In a class of twenty to thirty, there are usually one or two people who believe the costs were not worth it. The vast majority vote enthusiastically that Napoléon III’s project was a success. What do the French and in particular, the Parisians think about this? I don’t know. What I do know is there aren’t any memorials to Napoléon III commemorating his building efforts.

Is Napoléon III shunned because the French believe his project wasn’t necessary or unjustified or the cost was too great? I’m not sure I believe that since there are multiple homages to Haussmann (e.g., bd Haussmann). Perhaps it’s because Napoléon III was the last French “monarch” or emperor, both of which work against him. Maybe he has never been forgiven for allowing the Prussians to occupy Paris and ultimately, the disastrous uprising known as the Commune.

Burial in England

Originally buried in the Catholic church in Chiselhurst (London), Napoléon’s ashes were transferred to the Imperial Mausoleum within St. Michael’s Abbey, Farnborough. Eugénie had a crypt built for the remains of her late husband, son, and eventually herself. (Queen Victoria donated the three granite sarcophagi.)

Well, the French want him back now. Okay, only some of them want the emperor back. The deputy speaker of the French senate has initiated a campaign to have the remains of Napoléon III, Eugénie, and their son returned to France. The major roadblock is the Bonaparte family who don’t want their relatives moved out of England. Prince Charles Bonaparte (b. 1950) believes it would be easier for you to hop on the Eurostar and visit his relatives in Farnborough. (Charles is Napoléon III’s great-great-nephew.)

So, if the French want to “rehabilitate” the former emperor, does this mean they are in the mood to put up a statue?

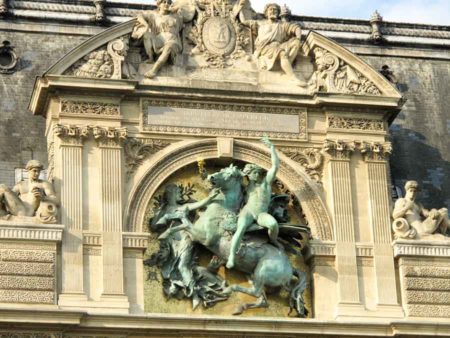

Commemorating Emperor Napoléon III

I know of only three places where you can see any evidence of Napoléon III’s existence. The first is on the side of the Pont au Change, a bridge connecting the Île de la Cité at the Palais de Justice and Conciergerie to the Right Bank at the place du Châtelet. Napoléon III ordered the bridge built in 1858 and his imperial insignia can be seen on both sides of the bridge. (Most people make the mistake of believing the “N” belongs to his uncle, Napoléon Bonaparte.) The second place where we are reminded of the former emperor is his monogram which he had carved on the façade of the Opera Garnier (i.e., Paris Opera). The third site where Napoléon III is mentioned is his “statue” above one of the entrances to the quai du Louvre. I don’t see a statue of the emperor but the plaque above the horse is dedicated to Napoléon III. This memorial commemorates his contribution to a significant expansion of the Louvre during the mid-1800s.

All three items I have mentioned were put in place during Napoléon III’s Second Empire. So, I really don’t think these really count as typical memorials are erected decades after the subject or event has passed on. (It’s kind of like our naval policy of not naming a ship after someone until they are dead.) In other words, the emperor ordered these memorials to himself.

It appears that Baron Georges Haussmann eventually came out on top in the “popularity” poll. He not only had a street named for him (Boulevard Haussmann), but the government erected a bronze statue of Haussmann. Plus, they allowed him to be buried in Paris in the family crypt in Père Lachaise cemetery. However, after 150-years, it seems the French want their last emperor back. Although the movement is underway to have the remains of Napoléon III returned to Paris, I suspect the majority of the French aren’t ready to embrace the Bonaparte family again. There are probably bigger issues at hand.

“He tried to make Paris a magnificent city and he succeeded completely. He introduced into his beautiful capital trees and flowers and populated it with statues.”

⏤ Jules Simon

Frequent critic of Napoléon III

Commenting after the emperor abdicated

Next Blog: “Two Footballers and a War”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Article:

Willsher, Kim. Notre Dame’s uncovered tombs start to reveal their secrets. The Guardian, 9 December 2022. Click here to read the article.

Article:

Peregrine, Anthony. Why the remains of Napoleon III are better off in Britain. The Telegraph, 15 February 2023. Click here to read the article.

DeJean, Joan. How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City. New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2014.

Hazan, Eric. The Invention of Paris. London: Verso, 2010.

Horne, Alister. Seven Ages of Paris. New York: Vintage Books, 2002.

Hussey, Andrew. Paris: The Secret History. London: Penguin Books, 2007.

Kennel, Sarah with Anne de Mondenard, Peter Barberie, Françoise Reynaud, and Joke de Wolf. Charles Marville: Photographer of Paris. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Kirkland, Stephane. Paris Reborn: Napoléon III, Baron Hausmann, and the Quest to Build a Modern City. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2013.

McAuliffe, Mary. Dawn of the Belle Epoque. Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2011.

Pitt, Leonard. Paris: A Journey Through Time. Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2010.

Pitt, Leonard. Walks Through Lost Paris: A Journey into the Heart of Historic Paris. Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2006.

Tindall, Gillian. Footprints in Paris. London: Chatto & Windus, 2009.

Crypte archéologique de l’île de la Cité. Click here to visit the web-site.

Musée de Cluny. Click here to visit the web-site.

★ Read Some of my Past Blogs About Medieval Paris ★

Please click on the links to read about some medieval Paris topics.

Pasties and Medieval Suppers Click here.

Paris Bridges Click here.

Gibet de Montfaucon Click here.

Flowers, Birds, Jewish Community, and a Murder Click here.

Charles Marville and Le Vieux Paris Click here.

Medieval Sleep Number® Bed Click here.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are getting ready for our river cruise in The Netherlands (click here to read the blog, Audrey Hepburn & Queen Wilhelmina and here to read May 5, 1945.) This will be the first of two river cruises for us in 2023. We follow up this trip with the cruise on the Elbe River in May. At the end of that cruise, Sandy and I will end up in Berlin ⏤ a first time visit for both of us. We will begin the research for our future book, Where Did They Put the Führerbunker? A Walking Tour of Nazi Berlin (1933−1945). Stay tuned as I will update you after that trip.

Our best wishes go to Stanley Booker for his 101st birthday this month! (click here to read the blog, Stanley’s Century).

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thanks to the following people who kindly reached out to us regarding past blogs:

Leonard D. asked us about a particular caption in the blog, Rendezvous with the Gestapo (Click here to read). Fortunately, I had not made a mistake. (Normally when someone points it out, an error has been committed.) Thanks Leonard. Friends like you keep me “honest.”

Victoria H. wanted to know where Suzanne Spaak is buried (click here to read the blog, Something Must Be Done). Well, her remains were exhumed and transferred at least twice, but I don’t believe anyone knows. At least I have not been able to ascertain her final resting place. Great question Victoria!

Caroline C. contacted me about the blog, The Sussex Plan and a Very Brave Woman (click here to read the blog). I think she was mildly upset that I had not mentioned her relative in the blog. Evelyne Clopet was tortured and executed by the Germans after her capture in August 1944. She was the radio operator for the “Colère” mission. Of six Sussex Plan agents dropped into France on 3/4 July, only one (André Rigot) survived. Sandy and I have decided to take off the month of August with regard to publishing new blogs. Instead, we will reprint two past blogs in an updated and expanded version. One of those will be The Sussex Plan and Caroline, I promise to update the content to include Evelyne. The other blog reprint will be Something Must Be Done.

Larry R. read our blog, Amazing Women of the SOE (click here to read the blog). His relative, Josephine Porter Winter, was an American woman who volunteered to drive an ambulance in France during World War II. Larry asked if I could assist him in figuring out how to get France to recognize Josephine for her brave efforts. I won’t go into details but through Larry’s considerable efforts, Josephine has now been officially recognized. Thanks, Larry, for allowing us to be part of your little journey (albeit a very minor part).

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books (in our case, it is Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?). The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please contact Stew directly for purchase of books, Kindle available on Amazon. Stew.ross@Yooperpublications.com or Contact Stew on the Home Page.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross

Always informative and a pleasure to read. Thanks, Stew.

Hi Greg. Glad to hear you enjoy reading our blogs. STEW