So you read the title of this blog and automatically assumed I was going to share my opinion with you concerning recent events around our country. You were interested to know what I thought about the desire and the movements to destroy or relocate certain statues, paintings, or other memorials that certain people might find offensive.

No, I wanted to talk with you today about the deliberate destruction of approximately 1,750 bronze statues throughout France during the German Occupation of World War II. Not since the French Revolution had so many statues been destroyed (albeit for different reasons).

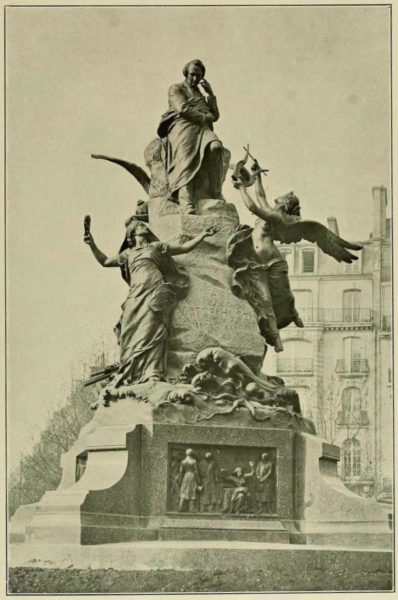

During the latter part of the 19th-century, the French government known as The Third Republic began a wide-spread campaign to erect bronze statues. These men (Joan of Arc being the lone woman) were considered heroes of France but in the minds of the citizens, they were closely associated with a widely considered corrupt government. This period of time was sarcastically dubbed “Statuemania.” Learn more.

What Happened?

Well, first of all, the Nazis invaded France on 14 June 1940 and began a four-year occupation. Hitler created two zones in France: The Occupied and Unoccupied (Paris was in the Occupied Zone). After seventy years in existence, The Third Republic was replaced by the Vichy government headed by Marshal Pétain and Pierre Laval.

Pétain’s collaborationist government was located in the small spa town of Vichy—the Unoccupied Zone. By November 1942 with the Allied successes in North Africa, all pretenses of a separate government were gone when the Germans eliminated the Unoccupied Zone and began to increase their direct role in running occupied France including higher demands for agricultural products and other resources (including non-ferrous metals) to feed the Nazi military machine. Learn more about the Vichy government here.

After France was liberated in August 1944, it became clear that Pétain and Laval had sanctioned laws, decrees, and actions that far exceeded Nazi expectations (including quotas for the deportation of Jews). During their separate trials, Pétain and Laval tried to argue in their defense that they were only trying to keep the Nazis happy and so avoid greater hardships for the French—at least as long as you weren’t a Jew, Freemason, communist, gypsy, homosexual, political opponent or any other type of untermensch (inferior person).

Reparations

The terms of the Armistice of 22 June 1940 were harsh. The French were required to cede three-fifths of France for German occupation. All occupation costs were to be paid by the French. Additionally, a daily fee of 400 million French francs was to be paid to the Germans. As time went on, the Germans confiscated more and more of the food to send back to the fronts as well as demanding higher payments in gold and other supplies.

Early in the Occupation, the Germans threatened to confiscate every church bell in France for the purpose of melting them down to make bullets (much like they did in all the other occupied countries). The Vichy government was very close to the Catholic Church and Pétain’s ministers countered with a plan to destroy and melt bronze statues instead of the bells. There was an immediate uproar by the citizens (as there would have been over the church bells). The Germans accepted this alternate option albeit with increased quotas for metal.

Vichy told its citizens the statue metal would be used for the national agricultural industry (the French knew better). In fact, the metal was always earmarked by Vichy to be shipped direct to Germany for the manufacture of German bullets and other munitions. It all counted towards satisfying the reparation fee.

Mobilization of Statues

Most people believe or assume this was a German initiative when in fact, there is no evidence to support this. Mobilization of the statues was strictly a French decision and was only one component in the overall metal recovery program.

One of the actions that Vichy took in October 1941 was to pass a law calling for the destruction of any statue which the Nazis might find offensive. These were any statues that symbolized democracy, liberal policies, religion (including persons of the Jewish faith), avant-garde, and generally, any idea or philosophy which was anti-Nazi.

French communities vigorously opposed this policy—Paris did not. Hundreds of towns went to great lengths to protest, condemn, and even hide the statues. Most of the statues were of local men who were considered heroes to the townspeople. Parisians did not have the same attachment to their statues. Almost all the statues in Paris were put up by The Third Republic and as previously discussed, represented a decadent time (also remember that Baron Haussmann had created a lot of open space by 1870 which needed to be filled). Statues erected during “Statuemania” included Voltaire, Diderot, Rousseau and revolutionaries such as Camille Desmoulins, Marquis de Condorcet, Georges-Jacques Danto, and Jean-Paul Marat. Politicians and icons of The Third Republic such as Léon Gambetta and Victor Hugo were immortalized. Other than Danton, none of the previously named statues made it. Victor Hugo’s granddaughter was unsuccessful in trying to save Victor’s statue and less than one week after its destruction, she died.

What was the criteria for selection? It was determined that if a statue was privately held or located in a cemetery, it would be saved. Statues of kings, queens, and saints were off limits. If a statue was considered to be of historical significance or “indisputable national glories,” it would be saved. Four statues were classified as historically significant: King Henri IV (Pont Neuf), Joan of Arc (Place des Pyramides), Louis XIV (Versailles), and Napoléon (Place Vendôme).

There were actually two waves of statue mobilization: October 1941 to May 1942 and the summer 1942 to August 1944. The first wave was controlled by the French and it was the period of greatest destruction. The second wave was controlled by the Germans and coincided with the elimination of the Unoccupied Zone and increasing control of the occupied country by the Nazis. The second wave was less damaging because there weren’t as many statues left to choose from and by early 1943, the German war effort was consuming more resources including manpower. Although the second wave coincided with the return of Pierre Laval in April 1942 to run Vichy and by extension, an increase in its collaboration efforts, the Nazis were more interested in exploiting French natural resources than they were of collaboration.

The mobilization peaked in October 1942. During the second wave, the Germans were ruthless with respect to their selection of statues. The final say belonged to the German Kunstschutz (the Wehrmacht art protection division—is this an oxymoron?). Statues previously safe (privately owned, cemeteries, and war memorials) were now fair game. By 1943, the Nazis were going after statues in the universities, lycées (high schools), and French administrative offices. Only two statues in Paris were saved by the Germans during this period: the Saint-Michel statue and fountain and the Medici fountain in the Luxembourg Gardens.

Destroyed Statues

Once the statues were identified for destruction, they were removed from their pedestals and taken to a scrap metal warehouse located at 112 Avenue du Général Michel Bizot (12e)—the building no longer exists. There they were disassembled, crushed, and melted down. Clandestine photos of the statues were taken by Pierre Jahan before being melted. These photos have been preserved in a book La Mort et les Statues (Death and the Statues).

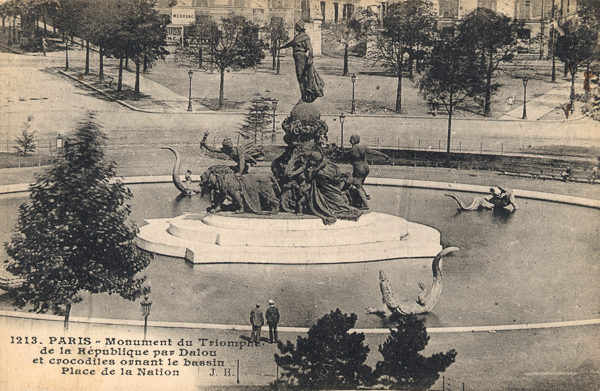

Some statues had sections removed while the core statue was left standing. A great example of this is The Grand Fountain in the middle of the Place de la Nation. It was once a shallow circular water basin with the main sculpture in the middle. Surrounding the center island were sculptures of lizards and alligators. These represented the enemies of democracy and so they were removed and destroyed. Other statues had their heads removed and were hidden from the authorities. After the war, these were remounted on the pedestals as busts.

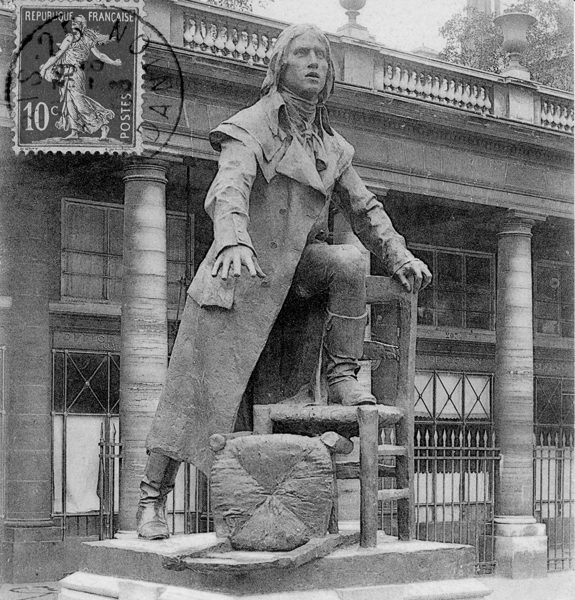

The Statue of Danton

When Sandy and I were in Paris doing the final research for the French Revolution books (Where Did They Put the Guillotine?), I happened to mention to her how surprised I was that we didn’t see statues of the leaders, martyrs, or principals of the French Revolution. Where were statues of Voltaire and Rousseau? The only bronze statue we found was Georges-Jacques Danton standing in the Place Henri Mondor next to the entrance of the Odéon Métro. A small statue of the Marquis de Condorcet had been erected rather recently on the Quai de Condi. That was it (there may have been more but we never saw any).

Now we know why there aren’t any of those statues. The only one I know that was replaced (at least in its original size and pose) was Condorcet. Why was the Danton statue saved when other revolutionaries’ statues were not (e.g., Jean-Paul Marat and Camille Desmoulins)? Was Danton considered to be of historical significance or “indisputable national glories?”

Decapitated Pedestals

So you pull down a statue from its pedestal. You know what will happen to the statue but what do you do with the pedestal? Three options: demolish it, leave as is, or replace the statue. The original plan was to demolish the pedestals but a lack of manpower and transportation made the destruction a very low priority to Vichy. After the war, all three options were exercised by local officials. Some towns kept the pedestals to be used as a soapbox for speeches.

Many of the pedestals in Paris were eventually demolished. The recast statue of the Marquis de Condorcet stands on the original pedestal. The statue of François Arago was never replaced and his pedestal remains unadorned near the Place Denfert-Rochereau.

For several French generations, the sight of empty pedestals was a constant reminder of the collaboration by Vichy France. I wonder how many of those passing by Arago’s pedestal today know the story behind the missing statue.

Paris Statues Today

As we walk around Paris, it becomes clear the relative number of free standing bronze statues in Paris is very small especially compared to other major European cities. There are many statues in the Luxembourg Gardens, in the exterior alcoves of the Hôtel de Ville (City Hall), and the cemeteries (e.g., Père Lachaise) but most are chiseled out of stone.

Right:Statue of Charles de Gaulle in the Place Clemenceau, Paris. Photo by BKP (April 2010). PD-CCA-Share Alike 3.0. Wikimedia Commons.

In volume two of our new book Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? we take you to an area where commemorative statues stand. Here you will find General Charles de Gaulle simulating his victorious walk down the Avenue des Champs-Élysées on 26 August 1944. General de Gaulle did not get his statue until 2000, thirty years after his death.

Paris seems to have two primary methods for memorializing its heroes: naming streets after them and putting plaques on the front of buildings that held some significance to the individual being honored.

I like historical plaques. I just need to learn French to fully enjoy them.

Historical Footnote

In the context of World War II, the Occupation of France (and other countries), and the overall suffering, our topic today is really quite minor. I would dare say that if you asked Parisians today about their knowledge of the statues, only a handful would have any idea of this historical footnote.

The mobilization of statues was neither cultural or historical revisionism. It was driven strictly by economic and collaborationist forces.

Recommended Reading

If you’d like to dig a little deeper into the history of Paris statues and their destruction during World War II and the Occupation, I recommend the following book:

Freeman, Kirrily. Bronzes to Bullets: Vichy and the Destruction of French Public Statuary, 1941−1944. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009.

Kirrily Freeman’s book Bronzes to Bullets is a very detailed account of the mobilization of statues in France. It reads like a PhD thesis—not surprising as this was the author’s thesis. It is well researched and Dr. Freeman presents a well-documented foundation based on economics, cultural, historical, and political events. She did a very good job of explaining the cultural and patrimony mindset of the French and its effect on their psyche towards the statue removals and destruction. I do wish she had commented on why the Danton statue was saved.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

This is our last blog before we go to Paris. Sandy and I will be in Paris for two weeks beginning 9 September 2017. We’re looking forward to seeing Raphaelle again. She will be our guide for three days while we visit several sites outside Paris. Our good friend Annette has business in Rotterdam and will take the train to see us on the second weekend—looking forward to closing down a bistro with her.

Please follow us on Facebook and Twitter as we will post each day. If nothing else, we’ll tell you about a good restaurant we’ve experienced that day.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thank you to Patti H. for her comments on our last blog Puttin’ on the Ritz. Hope you enjoy this one as well Patti!

Our next blog will be on TIME Magazine’s “Man of the Year.” Spoiler Alert: He was the only “Man of the Year” executed and he’s mentioned in this blog.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2017 Stew Ross