Monsieur Rémi Babinet purchased the beautiful building at 85-87, rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin in the former working-class neighborhood of Paris’s 10thdistrict. M. Babinet’s intent was to restore the abandoned late 19th-century building and move his advertising business there. Shortly afterwards, a historian approached him in the spring of 2009 with the news that M. Babinet’s building was used as a Nazi forced labor camp.

Babinet learned that his building had been confiscated by the Nazis and by 1943, it had become a giant distribution center and retail store for Nazi officers to shop in. The inventory was involuntarily supplied by Parisians who happened to be Jewish. The forced labor were Jews who had been arrested and detained at Drancy. Rather than being deported immediately to Auschwitz, they were transferred to Nazi department stores in Paris to work as clerks, laborers, and skilled craftsmen.

Did You Know?

Did you know that the Mousquetaires de la garde or, Musketeers of the Guard were the personal bodyguards of King Louis XIII? Alexander Dumas wrote the classic, The Three Musketeers, based loosely on the king’s guards (I suppose today, we would classify his book as “historical fiction”). This branch of the French military has essentially existed over many centuries albeit with different names but similar purposes. Today, its contemporary successor is The Republican Guard. This unit provides guards of honor for the State as well as security around Paris. Back in Napoléon’s day, his personal bodyguards were known as the Garde Impériale or, Imperial Guard (if I recall properly, didn’t President Richard Nixon try to do this in the early 1970s?).

The Imperial Guard was an elite group under the direct control of Napoléon. He carefully chose its members whom he expected to not only protect him but provide an elite fighting force during his battles. The “Old Guard,” as he called a select group of soldiers within the Imperial Guard, were the most seasoned soldiers in the French army, above-average height, and hardened veterans of battle campaigns. Only once did the Old Guard retreat without orders: the battle of Waterloo in 1814. After Napoléon was sent off to his final exile, the Old Guard disbanded. With the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, the Imperial Guard would morph into a different existence and name. Here are some interesting facts about the Old Guard:

*This unit was with Napoléon from start (1799) to finish (1814).

*Soldiers were required to be a minimum of six feet tall. Napoléon was 5’5” and while standing next to his bodyguards, he developed a reputation for being short when in fact, he wasn’t (at least compared to the average male height of 5’2”).

*The soldiers were the best dressed in the French military.

* They were the best paid and enjoyed superior grades to other soldiers of equal rank.

*Imperial Guard soldiers were given R*E*S*P*E*C*T by all other military personnel. Even lowly privates were addressed as “Monsieur” by officers.

*They were allowed to complain.

* They lived in relative luxury and ate the best food (nothing but the best for the emperor’s boys).

*Napoléon called each of them by their first name.

*Some of surviving members of the Old Guard donned their former uniforms to attend the ceremony at the Hôtel des Invalides when Napoléon’s remains were returned to Paris in 1840.

Paris Department Stores

For those of you who “shop ‘til you drop,” you are likely familiar with the four major Paris department stores. Le Bon Marché (24, rue de Sèvres; 7e) was built in 1838. The Bazar de l’Hôtel de Ville (36, rue de la Verrerie; 4e) opened its doors in 1852. Printemps Haussmann (64, boulevard Haussmann; 9e) began operations in 1865 while Galeries Lafayette (40, boulevard Haussmann; 9e) started in 1894. Right from the beginning, these department stores catered to the upper-class citizens of Paris. A lesser known store (with little-known history) was started to address the needs of the “working class” citizens or laborers as they were known.

Magasin Lévitan

The British founded a Paris department store in 1897 named Aux Classes Laborieuses and located it at 46-48, boulevard de Strasbourg. Following World War I, it was sold to Wolff Lévitan (1885-1966), a Jewish furniture entrepreneur, who had started a furniture factory and store in 1920. Originally located at 63, boulevard de Magenta, Lévitan moved his business to 85-87, rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin and set up his furniture retail store. He targeted working-class clientele living in and around the local neighborhood. At the top of the front façade, in blue, is the phrase, Aux classes laborieuses or, “To the laboring classes.”

The Nazis quickly confiscated Lévitan’s business and the inventory was liquidated in July 1941. For the next eighteen months, the building remained empty. In 1943, the store reopened for business only this time, as a household goods store selling stolen personal property of deported or self-exiled Jews.

After liberation, the French army took possession of the building and in December 1945, turned it back over to M. Wolff. He resumed operation as a furniture store but by the 1970s, the store was sold.

Möbel-Aktion

As soon as the Nazis marched into Paris in June 1940, the looting and confiscating of Jewish property began. Under the guidance of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), a systemic process of pillaging was set up by Alfred Rosenberg. Initially, it focused its attention on stealing artwork and other cultural items. By 1942, the Nazis broadened their criminal activities to include furniture and household goods.

In May 1942, the ERR instituted a program called Möbel-Aktion or, Furniture Action (M-Action for short). This was the all-encompassing program to loot Jewish homes in the occupied countries. Between May 1942 and August 1944, approximately 70,000 homes and their contents were confiscated (in Paris alone, 38,000 homes were looted).

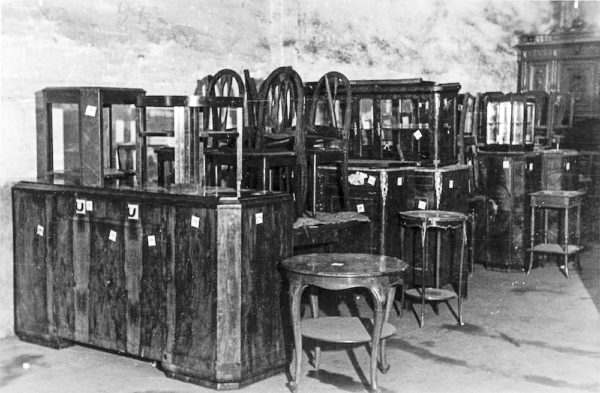

The process began with the French police knocking on the door in the evening and arresting the person(s) they were looking for (the police had extensive records of Jewish citizens living in the city including where they resided). The arrested person was told to leave their pets with neighbors and turn the keys over to the building manager (i.e., the concierge). Moving companies hired by the Germans came to the apartment and cleaned out everything. The goods were transported by truck to one of three locations, including Lévitan, where Jewish inmates unloaded the boxes. The boxes were opened, and the household goods were sorted into sections or departments: linen, dishes, flatware, glasses, bedding, armoires, toys, beds, tables, chairs, and instruments⏤personal effects were burned because it was useless to the Nazis. The goods were inventoried, photographed, and either sent back to Germany (for government administrative offices, units of the SS or, German citizens who were victims of Allied bombing) or sold through stores set up in cities such as Paris for the benefit of Nazi officers. It was not uncommon for a Jewish laborer to recognize their belongings or those of friends and neighbors. A similar situation occurred a hundred years earlier when surviving noble émigrés returned to Paris after the French Revolution and saw their former possessions for sale in the windows of retail shops.

Lévitan Was Only One of Three Paris Labor Camps

The first major round-up of Jews in Paris occurred on 16-17 July 1942 when more than 13,000 Jews were arrested (approximately 4,000 were children) with the majority of them detained at Drancy. The Drancy detention center was their final stop before deportation to Auschwitz and certain death. However, some of them convinced the Nazis they should not be deported as they were only half-Jewish, married to an “Aryan” or, spouses of French POWs. These individuals were used as slave labor, however, in the end, many of them ended up at Auschwitz.

Approximately 800 prisoners were used in the three sub-camps of Drancy which acted as repositories for the confiscated household goods. Besides Lévitan, there was Lager Austerlitz (43, quai de la Gare; 13e) and Bassano (2, rue de Bassano; 16e). The prisoners were used for sorting, packing, and loading. Some of them with specialized skills were put to work restoring the more valuable items. A total of 29,436 van loads (supplied by the Union of Parisian Movers) transported goods to the rail stations where 735 freight trains (27,000 rail cars) hauled the stolen goods back to Germany over the two-year period (art work was sent over to the Jeu de Paume).

Austerlitz had been used by the Germans since August 1940 as a warehouse for stolen goods. By the end of 1943, Jewish prisoners began working at the warehouse and stalls with goods not destined for Germany were set up. Workshops were established at Austerlitz to refurbish and repair musical instruments. Austerlitz lasted until 12 August 1944 when the Germans abandoned it. Fourteen days later, the last remnants of German soldiers bombed the building resulting in its complete destruction. Rebuilt after the war, the second building was demolished in 1997.

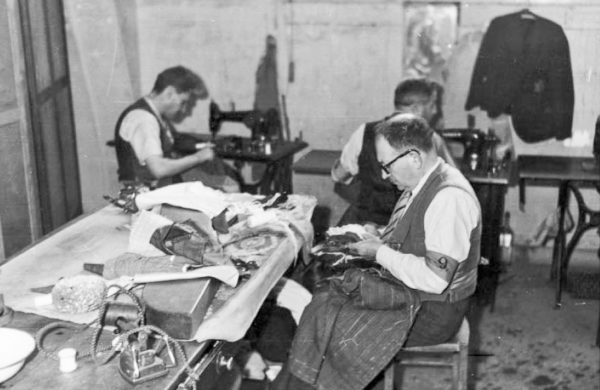

The Bassano sub-camp was located in the former Hôtel Cahen d’Anvers. Similar types of operations existed at Bassano as they did at the other two sub-camps. However, documentation was found which reflected a unique aspect of Bassano: the prisoners were forced to run a haute couture (i.e., fashionable dress) shop for the wives, girlfriends, and mistresses of Nazi officers and government officials.

Liberation

On 17 August 1944, Drancy and two of its sub-camps, Lévitan and Bassano, were liberated. A total of 795 prisoners worked at the camps. Unfortunately, 160 were deported to Auschwitz and never returned to their homes and what was left of their families. The Gestapo “owned the rights” to the inmates and would periodically conduct arbitrary selections and deport groups of prisoners to Drancy and then onto Auschwitz. Those who survived were primarily half-Jews, Jews in mixed marriages, or had special skills the Nazis needed. After the war, they did not talk about their experiences in Drancy’s sub-camps. There was a certain guilt factor that they had survived and could not bear to talk about any comparisons with those who experienced the horror of the death camps.

The story of the Nazi pillaging of personal property and these three Drancy sub-camps fell through the cracks of history primarily because of a lack of scholarship efforts. Today most historians believe the sacrifice of personal property was secondary to the loss of life. The famous Nazi hunter, Serge Klarsfeld, agrees. He believes the real tragedy was the murder of 76,000 French Jews and that the French government was an accomplice in these murders.

Perhaps what is lost here is that the pillaging of Jewish property really is an important story because it was just another example within the context of the demented Nazi philosophy and “Final Solution” to exterminate the Jews.

N’OUBLIONS JAMAIS.

NEVER FORGET.

Recommended Reading and Viewing

Dreyfus, Jean-Marc and Sarah Gensburger. Nazi Labour Camps in Paris: Austerlitz, Lévitan, Bassano, July 1943-August 1944. Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2013.

Gensburger, Sarah. Witnessing the Robbing of the Jews: A Photographic Album, Paris, 1940-1944. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015.

Sebba, Anne. Les Parisiennes: How the Women of Paris Lived, Loved and Died in the 1940s. London: The Orion Publishing Group Ltd, 2016.

Jean-Marc Dreyfus is the independent historian who approached M. Babinet with the story of Nazi looting and the history of the Lévitan building. Sarah Gensburger was a young student working on her PhD and together, the two of them did the research and wrote the above history of the Paris labor camps.

Several years later, Sarah published her book using the images discovered in a photo album which documented Lévitan and its role during the Nazi occupation years. This album was found by one of the Monuments Men and turned over to the German National Archives where it now resides in Koblenz.

Very little is written about Lévitan and the Drancy sub-camps using slave-labor. Dreyfus and Gensburger’s work seem to be the authoritative accounting of this story.

I highly recommend Ms. Sebba’s book as it is a very enjoyable read and she gives her readers an excellent description of what it was like living in Paris under the Nazi jackboot.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

We are in Singapore aboard the ms Maasdam, a Holland America ship. We’ll be cruising around Southeast Asia for three weeks while visiting five countries.

You are invited to join us via our Pinterest board. Please go to your Pinterest site and use stewrossdiscovers to access our daily pictures. If you don’t have a Pinterest account or are unfamiliar with this media site, please contact Sandy at sandy.ross@yooperpublications.com and she will gladly walk you through the process.

By the way, if you visit Paris and you have never been inside one of the four major department stores, make sure you set aside some time to visit one of them. We were in Le Bon Marché last year and what an experience. Don’t even think of them in terms of American department stores . . . no comparison!

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank my friend, Arthur M., for passing a question I had about the Special Executive Operations (SOE) to another expert on the SOE, Patrick Y. I received Patrick’s detailed response within a day, and it cleared up something that I didn’t want to write about in the new book unless I was one hundred percent certain it was true (Patrick pointed out it was “fake news” ⏤ my term, not his but same end result).

So, thank you Patrick for saving me from looking like a dope.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you. The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs. Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright ©2019 Stew Ross