I thought perhaps you might like to read about a site I’ve decided to include in the first volume of our new book series, Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? A Walking Tour of Nazi-Occupied Paris. For those of you who have read one or more of my prior books, you know that four walks are included along with a section called “Métro Walks.” Each of the four walks has multiple stops and you can walk from one stop to the next without having to jump on the métro. However, there are sites that are interesting, but I couldn’t fit them into any of the walks or they are stand-alone stops accessible by means other than the métro. Typically, I include four of these sites in each book. For example, in volume two of the book, Where Did They Burn the Last Grand Master of the Knights Templar? A Walking Tour of Medieval Paris, one of the Métro Walk stops is Château-Gaillard. This is the castle built by King Richard the Lionheart after he was released from captivity in 1194 by Leopold V, Duke of Austria. It has a very interesting history and the castle’s ruins are situated on a hill overlooking the Seine River and easily accessible by car.

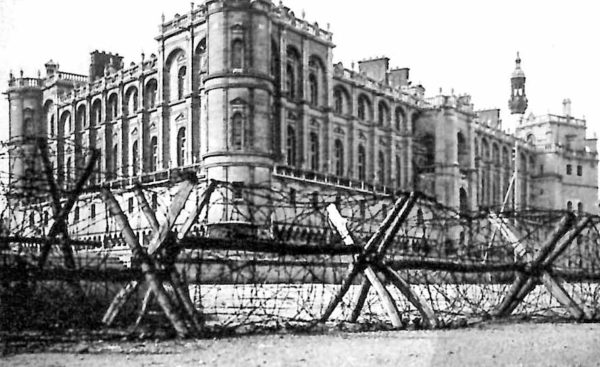

Today’s subject is in the town of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a suburb of Paris about seventeen miles (twenty kilometers) to the west. It also sits on a hill overlooking the Seine. Its strategic location was one of the reasons why Hitler chose Saint-Germain-en-Laye as headquarters for the Oberbefehlshaber West (Ob West), or German Commander-in-Chief in the West. It is a somewhat compact town and perfect for walking to the numerous bunkers built by the Germans as well as their command headquarters. It is also a town with quite a bit of French history.

Did You Know?

Did you know that the British government had the opportunity to stop Hitler in September 1938? In fact, the British were given multiple opportunities and had they supported the German military conspirators, their coup would have likely toppled the Führer.

Hitler was setting the stage for his invasion of Czechoslovakia. His orders to the military were to be ready for a 1 October 1938 invasion. The pretense of invasion was to protect and absorb the Sudetenland (a portion of Czechoslovakia populated by Germans). The real reason for the invasion was because Hitler wanted to destroy the country.

A German conspiracy to overthrow Hitler was underway with the involvement of his top military staff. (It was known as Septemberverschwörung, or the September Conspiracy.) The military wasn’t so much against conducting a war as they believed it was too early. The generals felt that going to war too soon would result in Germany’s defeat. If Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia and the British and French (and likely the Soviets) honored their treaties and agreements, German military forces would probably have been crushed by superior forces. Only the military had the power to usurp the Führer from within and General Franz Halder (1884−1972), chief of the army General Staff (OKH), recruited high-ranking Wehrmacht officers such as Gen. Karl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel (1886−1944), Admiral Wilhelm Canaris (1887−1945), and Gen. Georg Thomas (1890−1946). However, these men were desk jockeys and for the plan to be successful, generals with troop commands were needed. These included Gen. Erwin von Witzleben (1881−1944), Lt. Gen. Walter von Brockdorff-Ahlefeld (1887−1943), Maj. Gen. Paul von Hase (1885−1944), and Lt. Gen. Erich Hoepner (1886−1944).

The conspirators sent several agents to London to inform the British government that Hitler was ready to invade on 1 October and that if the British and French stood by Czechoslovakia, the German military was ready to overthrow Hitler. The message was delivered to the British prime minister (Chamberlain) who rejected it. On 2 September, Halder sent his own emissary to London to meet with the War Office and Military Intelligence⏤the British were not impressed. A third and final attempt was made on 7 September to convince the British to support the proposed coup. This time, the effort was coordinated through the German Embassy in London. The message was delivered to Lord Halifax, foreign secretary, who passed it onto the prime minister. Unfortunately, Chamberlain was talked out of taking any action by his ambassador to Berlin (he was in favor of Germany gaining possession of the Sudetenland).

Europe and the world were days away from the start of a war when Hitler postponed his attack on Czechoslovakia and invited the prime ministers of England and France to meet with him in Munich. At the meeting, the leaders met all of Hitler’s demands and more. Chamberlain returned to England pronouncing “I believe it is peace in our time.” (Hitler marched into the Sudetenland unopposed without any bloodshed.) Churchill didn’t buy it. He told the prime minister, “You were given the choice between war and dishonor. You chose dishonor and you will have war.” Less than a year later, World War II began after Germany invaded Poland.

Because of the Munich Agreement, the September Conspiracy was never carried out. Six years later, many of the original conspirators were involved with the 20 July attempt on Hitler’s life. Most of them were caught and executed in August 1944.

Saint-Germain-en-Laye

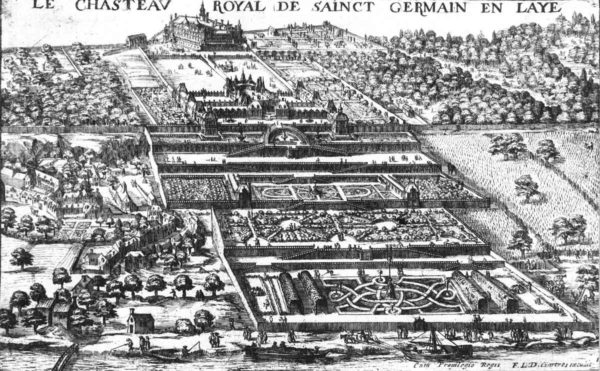

The town of Saint-Germain-en-Laye dates to the eleventh century when Robert II, the Pious, built a monastery dedicated to Saint Germain. (It was located on the site where the Church of Saint-Germain now stands.) The surrounding forest became a favorite hunting area for the kings and in 1124, King Louis VI built a royal residence called the “Grand Châtelet.” For the next five hundred years, Saint-Germain-en-Laye was considered a “royal town” and it became the residence of various French monarchs.

During the reign of Louis IX (r. 1226−1270), the Grand Châtelet was expanded, and the Chapelle Saint-Louis was built to house the Crown of Thorns. (This chapel predated Sainte-Chapelle located on the Île de la Cité in Paris where the Crown of Thorns were relocated in 1248.) During the Hundred Years’ War (1337−1453), the Grand Châtelet was destroyed by the English. Twenty years later, King Charles V rebuilt the castle and turned it into a fortress. The only surviving building from Louis IX’s building period was the medieval Holy Chapel. King François 1er came along in 1539 and expanded and reconstructed what became known as the Château Vieux, or Old Castle. Today, it is known as the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

Château-Neuf

After Henri II became king in 1547, he decided to build a new castle, or Château Neuf. The construction did not finish until 1600 during the reign of Henri IV. The Château Neuf and its immense gardens were built on the vast slope situated between the Château Vieux and the Seine. The castle was originally built as a central, one-level structure framed by four pavilions. Henri IV added the gardens and built seven successive terraces down to the river. Each terrace was linked by elaborate stairs and ramps. Louis XIV was born in one of the pavilions on 5 September 1638. Louis XIV would later abandon Château Neuf and move his court to the Palace of Versailles. After the English executed King Charles I in 1649, his son (the future Charles II), sought refuge in France and stayed in the castle until the restoration in 1660. By 1777, Château Neuf was in bad shape and Louis XVI gave it to his brother who intended to restore the castle and its grounds. Demolition began but, the French Revolution intervened, and the property was confiscated and later sold to an entrepreneur. The castle and the gardens were dismantled, and the property divided into lots to be sold. All that remains today is the Pavilion Henri IV (where Louis XIV was born) and two ramps of a terrace (at the end of rue Thiers). The original pavilion is part of the luxury hotel, Hôtel Pavillon Henri IV. On 3 March 1942, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) attacked the Renault factories. One of the bombs damaged part of the original pavilion and it was later demolished (the site is now used as a parking lot next to the Pavilion Henri IV).

Oberbefehlshaber West

Oberbefehlshaber West was the overall commander of German armed forces located on the Western Front (known as the Westheer). Ob West reported directly to the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), or Armed Forces High Command. In reality, Ob West had very little authority. By the time the German army occupied Europe, Hitler was the supreme commander and made all military decisions. The Wehrmacht reported to the Führer, the Luftwaffe to Hermann Göring, the navy to Admiral Erich Raeder, and the security forces (i.e., Schutzstaffel, Sichersdienst, and Gestapo) to Heinrich Himmler. The only real task assigned to Ob West was to build the Atlantic Wall as a defense against an Allied invasion. Even with that, Organisation Todt (OT) was given the responsibility to design and build the defensive network and the OT reported to Albert Speer, not to Ob West. (Click here to read the blog, The Good Nazi.) After the military campaigns in North Africa (1941−1943) and Italy (1943), Generalfeldmarshall Erwin Rommel (1891−1944) was put in charge of the western defenses in November 1943. Rommel and Rundstedt did not see eye-to-eye on the details creating considerable friction between the two field marshals.

There were five commanders between 10 October 1940 and 22 April 1945. Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt (1875−1953) served three separate assignments: 10 October 1940 to 1 April 1941 (he was transferred to a senior command position in the Soviet Union conflict); 15 March 1942 to 2 July 1944; and 3 September 1944 to 11 March 1945.

Rundstedt was replaced in May 1941 by Generalfeldmarschall Erwin von Witzleben (1881−1944; executed as a conspirator in the 20 July plot). After Witzleben took a leave due to illness (or forced out), Rundstedt returned for his second tour as commander beginning in March 1942 after Hitler dismissed Rundstedt for authorizing a withdrawal of troops in November 1941 against the Führer’s orders. Rundstedt “retired” in July 1944 (Hitler dismissed him a second time for insubordination) and was replaced by Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge (1882−1944). Kluge was one of the major conspirators of the 20 July plot against Hitler and committed suicide after realizing his role had been uncovered. Hitler assigned Generalfeldmarshall Walter Model (1891−1945) to be the temporary commander of Ob West and seventeen days later, the Führer reinstated Rundstedt to Ob West for the third and last time. However, by September 1944, Saint-Germain-en-Laye had been liberated by the Allies, and Rundstedt set up his “new” Ob West headquarters near Koblenz, Germany. After the Allies crossed the Rhine River, Rundstedt was replaced by Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring (1885−1960) who served less than two months before the Germans were defeated.

OB West Command Headquarters

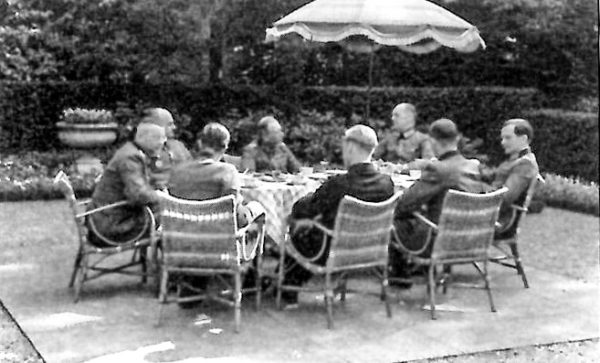

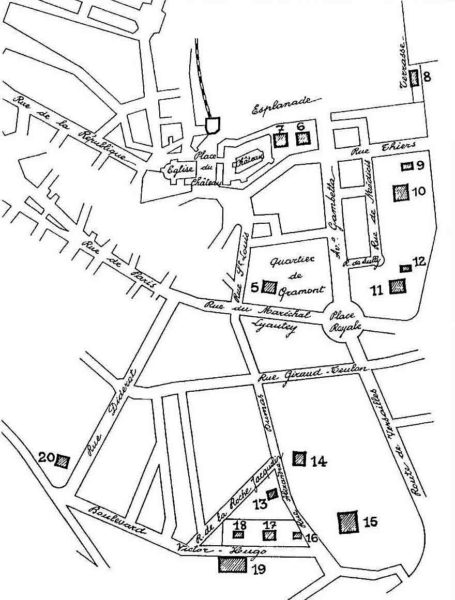

Rundstedt made the decision to set up his first command headquarters in the Pavilion Henri IV. Across the street is the former residence of Louis Louis-Dreyfus (1867−1940), commonly referred to as the “richest man in France.” (His great-granddaughter is the actor, Julia Louis-Dreyfus.) During his first assignment, Rundstedt confiscated the mansion for his residence and office. (Some accounts have him staying in the pavilion with his office in the mansion.) Various offices of Ob West took over local schools while the barracks were located at the Quartier Gramont. Villas and apartments were requisitioned for officers and staff. (Most of the residences in the Cité Médicis were taken over by the German officers.) Eventually, Rundstedt moved his residence to the Villa David that stood on the grounds of Lycée de Jeunes Filles. (Today, it is the administrative building for Collège Marcel Roby.) During the winter, most of the officers of Ob West, including Rundstedt, relocated to the Hôtel George V in Paris and returned to Saint-Germain-en-Laye in the spring.

After conquering Europe, Hitler turned his attention to Great Britain. When it became clear that England would not voluntarily capitulate, Hitler ordered his military to plan for the invasion of England. The task of creating the plan fell to Rundstedt and his staff with much of the planning done at the Pavilion Henri IV. The success of Operation Seelöwe, or “Sea Lion” was dependent on the Germans neutralizing the RAF and the British navy (both of which never occurred). Admiral Raeder knew the Germans could not invade Britain, but the Wehrmacht went along with Hitler’s plans until Gen. Alfred Jodl (1890−1946) expressed his concerns to Hitler about the plan’s viability (reportedly, Rundstedt never believed Operation Sea Lion would take place). Hitler postponed Seelöwe indefinitely and in June 1940, turned his attention to planning the invasion of the Soviet Union which he gave the code name, Operation Barbarossa. Click here to read the blog Professor Dr. Six.

The red-bricked pavilion was built in 1556 by Henri II. In September 1638, the future King Louis XIV was born in the living room of the pavilion (today, one of the salons). It opened as a hotel in the 1800s and over the years, many famous people resided here. During the 1840s, Alexandre Dumas père wrote The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte-Cristo while staying at the hotel. During the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71, the hotel and pavilion became the headquarters of the German General Staff. The former French prime minister and first president of the French Third Republic, Adolphe Thiers (1797−1877), resided here during the last four years of his life. Other guests identified by the hotel’s guestbook include Georges Sand, Victor Hugo, and Sarah Bernhardt. Today, the Pavillon Henri IV is a 4-star hotel with forty-two rooms, a restaurant, and reception rooms. It is designated as a French historical monument. Click here to visit the hotel web-site.

Rundstedt’s Second Tour

After being relieved of duty on the Eastern Front in December 1940, Rundstedt was ordered back to Saint-Germain-en-Laye in March 1942 to take over Ob West from Witzleben. (The 20 July 1944 plot to assassinate Hitler called for Witzleben to take overall command of the German military.)

About two weeks after Rundstedt returned to Ob West, Hitler gave the order for the defense of the west, in other words, building the Atlantic Wall. Rundstedt was given responsibility for overseeing the construction of the strategic defenses (as previously mentioned, it really fell into the lap of the OT and Albert Speer along with Generalfeldmarshall Erwin Rommel).

Rundstedt loved nature and gardens. Every day at 4:30 p.m., Rundstedt would invite his senior officers to the courtyard behind the Villa David to enjoy a cup of tea. Few security measures were set up for the protection of German soldiers or officers⏤Germans and the French came and went as they pleased. Rundstedt always took his two-hour morning walks alone and unarmed. He was fond of striking up conversations with people he met along the way and passing out chocolates to the children. He refused to be afraid of the bombs and would not allow any bunkers to be constructed. However, that changed in March 1942.

During the evening of 3/4 March, British bombers targeted the Renault factory. Stray bombs killed 367 French citizens, and several hit the building standing near the Pavilion Henri IV. After this incident, Hitler ordered the OT to build a command bunker near the Villa David as well as others scattered around the town.

The Bunkers

The OT built more than twenty bunkers in the town. There were two basic types of designs. The majority were considered shelters, or passive bunkers. These were used as command or communication centers, and to protect the troops from the bombs. The others were blockhouses (i.e., shooting posts and pill boxes) used for active combat defenses⏤primarily to set up machine guns. The best example of a shooting post is located at 4, rue Félicien-David. Another defensive combat position is 13, rue des Monts-Grevets where a gun-turret was placed in the garden. There were too few defensive bunkers to really provide much of a fight against the enemy. The shelters were built either above ground or underground (as we typically think of a bunker) or in some cases, both.

The OB West Bunkers at Saint-Germain-en-Laye

| LOCATION | FATE | |

| 1 | Blockhouse; Place Berteaux | Removed in 1954 |

| 2 | Blockhouse; Rue Diderot | Removed |

| 3 | Blockhouse; 4, rue Félicien-David | |

| 4 | Blockhouse; 13, rue des Monts-Grevets | |

| 5 | Shelter; Quartier Gramont | |

| 6 | Shelter; Cité Médicis | |

| 7 | Shelter; Parc du Château | |

| 8 | Underground shelter; Pavilion Henri IV | |

| 9 | Shelter; 16 ter, rue Thiers | Removed in 1962 |

| 10 | Shelter; 1, rue Salomon Reinach | Removed in 1982 |

| 11 | Shelter; Saint Erembert School | Removed in 1982 |

| 12 | Shelter; Saint Erembert School | Removed in 1987 |

| 13 | Underground shelter; Collège Marcel Roby | |

| 14 | Shelter; 25, rue Alexandre Dumas | |

| 15 | Underground shelter; rue Alexandre Dumas | Filled in 1962 |

| 16 | Shelter; Lycée Jeanne d’Albret | |

| 17 | Shelter; Lycée Jeanne d’Albret | |

| 18 | Shelter; Lycée Jeanne d’Albret | |

| 19 | Shelter; Command headquarters – rue Félicien-David | |

| 20 | Shelter; 13, bd Victor Hugo | Now a garage |

| SO-150 | Shelter; Collège Marcel Roby | |

| SO-151 | Shelter, 12, rue Félicien-David | A reception center built on top |

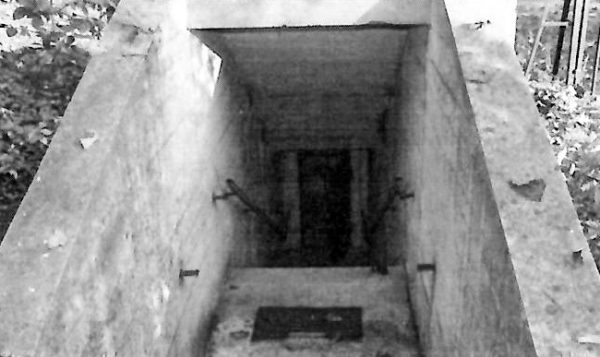

Only three of the bunkers were completely underground. The first, number eight above, was built below the terrace next to the Pavilion Henri IV. The concrete roof was relatively thin and would not have sustained a direct hit. Number fifteen above was built into an existing cave and it was filled in during 1962. The third underground bunker (number thirteen) was built as the personal shelter for Rundstedt. Located in the gardens of Villa David, a tunnel connected the bunker to the villa. This small bunker is sometimes confused with number nineteen that was the large shelter bunker for Ob West command center. Reportedly, the interiors of both bunkers remain in relatively good condition.

The main Ob West headquarters bunker (number nineteen) was built next to a quarry and the OT used cavities in the quarry as part of the structure. The shelter was very large consisting of forty rooms, two stories, and numerous passages, corridors, and toilets. About 100,000 tons of concrete was used and crews worked around-the-clock for eight months.

Rundstedt refused to enter the bunkers and he was less than pleased that the Villa David bunker destroyed part of the garden he enjoyed spending time walking around. Hitler knew of Rundstedt’s opposition and ordered the building of the bunkers to be done while Rundstedt was away.

Postwar Bunkers

After the war, the French government made the decision to classify the Saint-Germain-en-Laye bunkers into three categories: those deemed necessary to the defense of France (the government took ownership), those on private property that would be handed over to the owner with their promise not to demolish the bunker, and those that could be abandoned with the owners making the final decision what to do with the bunker.

By 1947, the study was completed, and twenty bunkers were identified and classified into one of the three categories. The study missed two bunkers and they are listed above as SO-150 and SO-151 (they still exist).

The French army was going to use the former command bunker but decided it was too old for new technology and equipment and the bunker was abandoned by 1954. The command bunker is now owned and maintained by the Musée d’Archéologie in the nearby Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. The museum uses the bunker to store original molds of statues from the Napoléon III era. Click here to visit the museum web-site.

The town leaders made the decision not to destroy the bunkers turned over to property owners because of the high demolition costs. So, many were left on an “as is” basis and entrance is forbidden. Some are now used as storage facilities while others have been left to nature. The citizens are not proud of the bunkers and the role the town played during the occupation and prefer to not talk about them. (Although Raphaëlle did find several people who were very talkative.) As one mayor put it, “It was not a happy page of our history. It was traumatic for the residents.”

★ Learn More About OB West ★

Blumentritt, Günther. Von Rundstedt: The Soldier and the Man. London: Odhams Press, 1952. (General der InfanterieBlumetritt was Rundstedt’s chief of operations.)

Messenger, Charles. The Last Prussian: A Biography of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, 1875−1953. South Yorkshire, UK: Pen and Sword, 2011.

Pallud, Jean Paul. 2008. “The OB. West HQ at Saint-Germain-en-Laye.” After the Battle, Number 141, pages 2 through 33.

Shirer, William L. 20th Century Journey: A Memoir of a Life and the Times. Volume II: The Nightmare Years 1930−1940. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1984.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same applies to internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

We have completed the revision of volume one of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? If you recall, the decision was made to expand the series from two volumes to three. The only major change for volume one was to move two Métro Walks (“Musée de la Libération de Paris” and “Mémorial de la France Combattante”) to future books and replace them with “Oberbefehlshaber West” and the “Musée de la Résistance nationale.”

Since this was a last-minute change and we were not able to get over to France to visit these sites, Raphaëlle Crevet kindly agreed to visit them and assist us in creating content and images for the two stops.

We will begin the editing process on the new content within days and it shouldn’t take much time for Roy to wrap up the new book and get us a galley for final review before the book goes to our printer in Nashville.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

In keeping with the above comments, I’d like to thank our good friend, Raphaëlle Crevet, for taking the time to go to Saint-Germain-en-Laye and do some research for us. She walked the village, saw many of the bunkers, and talked with some of the villagers. She was kind enough to supply us with many photographs, some of which I’ve included in this blog. I know her commentary, photographs, and experiences will find a place in the new book. Raphaëlle is a professional and credentialed private guide. For many years, Raphaëlle has been our “go to” person for sites in and around Paris. If you are planning a trip to Paris and have an agenda, I highly recommend you talk with Raphaëlle about setting up a private tour. You won’t be disappointed. You can either contact Raphaëlle directly (raphaellecrevet@yahoo.fr) or reach out to me and I would be happy to make the introduction.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2021 Stew Ross

Well done,

All ‘Now’ After the Battle photos were taken by me in 2088,

Jean-Paul Pallud,

Please replace ‘anonymous’ by Jean-Paul Pallud,

Thank you,

Yours,

Bonjour M. Pallud; Thank you for contacting us and letting me know you were the photographer on those images. I try very hard to make sure the image captions are correct and give proper credit to the photographers. I tried contacting the magazine for that information but never heard from them. We will update the blog immediately to give you the credit for the black and white contemporary photographs. I will contact you shortly when the changes have been made. Again, thanks for pointing this out. I hope you enjoy our blogs, both past and present. STEW