It takes a special event to pull Sandy and myself away from the television when the British Open takes over our weekend. Yet, it happened this year. Right in the middle of the Open on Sunday, we spent over four hours watching a 1971 Oscar® nominated documentary film.

I’m deep into my research for the next book, Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? A Walking Tour of Nazi Occupied Paris (1940–1944). Right now I’m focusing on the French Resistance, its members, and the foreign agents that supported the resistance movement. As part of the research, I’m “meeting” many brave men and women who were real Résistants—not the ones who put the armband on when it became clear the Allies were close to liberating the country (and Paris) in the summer of 1944. These incredible people were the resistance fighters who knew what the ultimate penalty would be for being captured by the Nazis and turned over to the Gestapo.

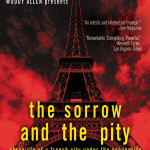

The film, The Sorrow and the Pity (original title: Le Chagrin et la pitié: Chronique d’une ville française sous l’occupation), is a documentary by Marcel Ophüls and André Harris. Filming took place in 1969, a very short 25-years after the end of the occupation. It is four hours of actual footage from the period we know as the Occupation of France and in particular, the effects it had on a small French town called Clermont-Ferrand. Along with original footage, many of the participants were interviewed. These interviews included members of the resistance, collaborators, traitors, citizens of Clermont-Ferrand, politicians of the Vichy government, Free French, and England, foreign intelligence agents, and a German officer and soldier stationed in Clermont-Ferrand.

THE SORROW AND THE PITY

As I’m sitting there watching this, I realize I know many of these players. I’ve read about them in my books. For 4 hours, they all come alive in front of me. I watch the interview with René de Chambrun and I’m astonished at his spin (basically denying) on his father-in-law’s brutality towards French citizens (Pierre Laval, president of Vichy France, signed the orders to deport all Jewish children to the extermination camps—he was executed after the Liberation). One sits there astounded by the continued arrogance of the German officer (he still wore evidence of his medals on his suit) as well as the denials by the Germans of the atrocities perpetrated by the Nazis. Every once and a while, you would catch someone in a lie because they would contradict themselves (the person interviewing them did an excellent job of countering their lies and statistics). You watch and listen to the farmer describe how he was denounced by a fellow villager, captured by the Nazis, and deported. He returned to the village knowing who the person was that turned him in and made the decision not to seek revenge. I could go on and on and on.

It was not only a time of great bravery but also a time of great suffering. Anthony Eden (Churchill’s Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs) was interviewed and said that if someone had not experienced living during an occupation by a foreign entity, they were not entitled to pass judgment on the country or its citizens. While I understand what he was trying to convey, I’m not entirely convinced he was right. Collaboration with the enemy is a tough subject. It was so difficult that an entire country decided to not deal with it or recognize its complicity until 16 July 1995 when French President Jacques Chirac stated the obvious in a speech: the French government (Vichy) had a responsibility to acknowledge its role as collaborators with the Germans and the role its police state played in the arrests and deportations of the Jews and other French citizens.

Collaboration and collaborationists is a subject unto itself. I touch briefly on this in my blog post from early 2015 entitled, Coco Chanel: Nazi Collaborator or Spy?—René de Chambrun was Coco Chanel’s attorney. It is a subject that will be front and center in my new book. I will take you to the places in Paris where these activities took place—some nice and some not so nice.

This film was banned in France until 1981 when it was shown on television.

Do we have a lot of stories? Of course we do. I’m looking forward to sharing these with you. Please continue to visit our newsletter and blog. Perhaps you’d like to subscribe so that you don’t miss out on the most recent newsletter and blog posts.

Thanks so much for following my newsletter and blogs as well as my little journey through this incredibly interesting process of writing a series of niche walking tour books based on European historical periods or events.

Please note that I do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies I mention or promote in my blog.

Are you following us on Facebook and Twitter?

Share This:

Copyright © 2015 Stew Ross