Today we’re going to introduce you to a brilliant woman whose contributions in both world wars of the twentieth-century ensured Allied victories. After World War II, her efforts were shoved aside, and others took the credit while her extraordinary skills were, and this is putting it mildly, underutilized. However, in today’s world when we bemoan the lack of women in the field of writing code, a century ago, Elizebeth Smith Friedman was a ground-breaking cryptanalyst or, codebreaker. In other words, she did the complete opposite of writing code ⏤she broke it.

Did You Know?

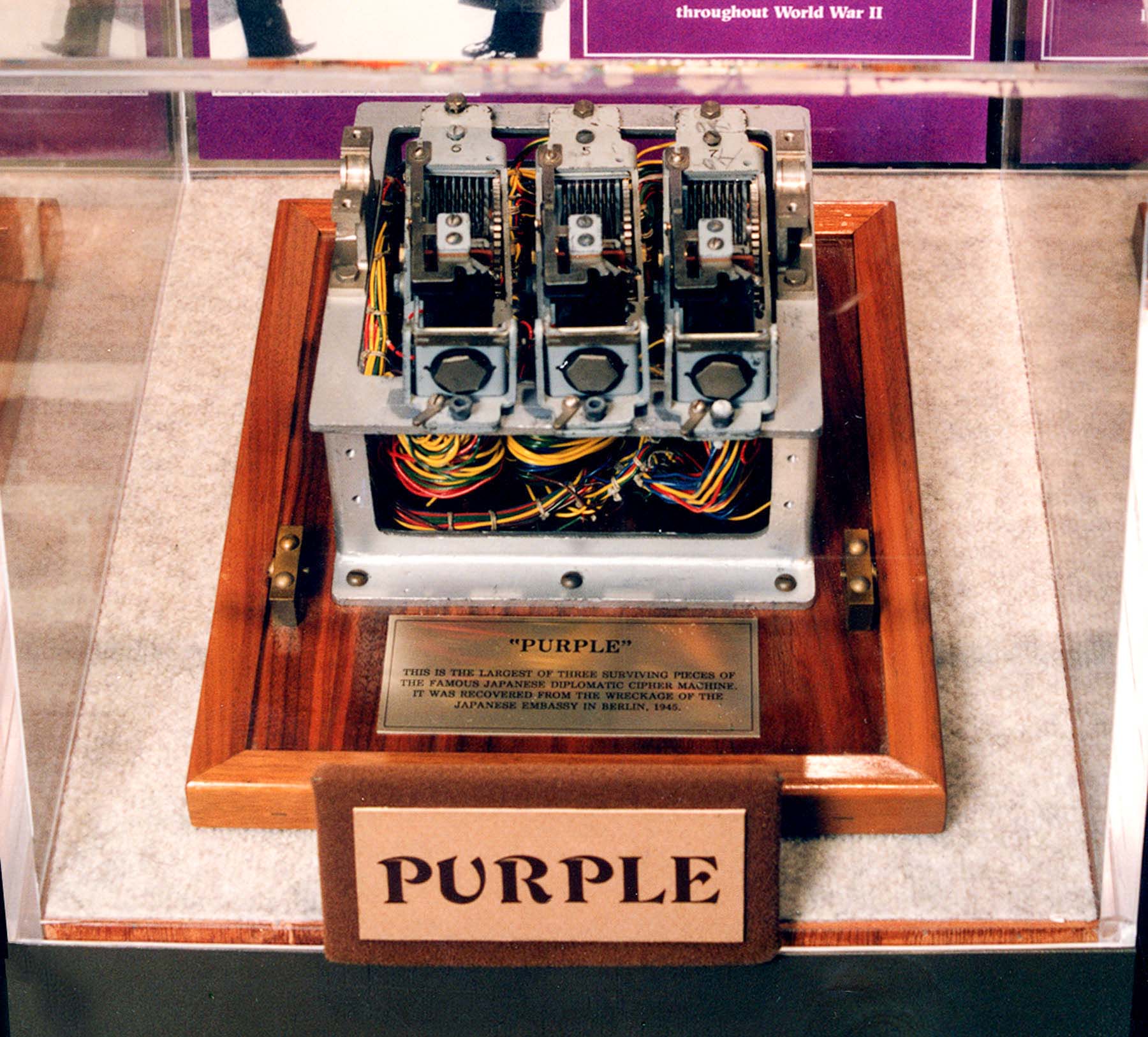

Did you know that the Japanese had an encryption machine similar to the Nazi’s enigma machine? The Allies called it the “Purple Encryption Machine.” After the Japanese learned that the Americans had broken their code in 1936, they developed a new system to encipher their messages. The Japanese called their new machine the “97 Alphabetical Typewriter” or, better known to the American spy organizations as “Purple.” It was made up of two typewriters with an electrical rotor system and a 25-character alphabetic switchboard. The machine was actually an improvement over the Nazi enigma machine. Without going into a lot of technical stuff (because I don’t understand it), suffice it to say, “Purple” was extremely difficult to crack. The U.S. Army hired William Friedman in 1939 to break the “Purple” code. It took Friedman and his team almost three years to fully decipher “Purple.” In the process, Friedman had a mental breakdown and was hospitalized. Despite never having seen an actual “Purple” machine, Friedman’s team was able to reconstruct one and produced eight functional replicas. Two years into the war, the Allies were able to track the Japanese navy’s movements as well as other military communications. Friedman had cracked enough of the “Purple” code by 1941 to learn the Japanese would attack Pearl Harbor. Unfortunately, this knowledge was never used.

Let’s Meet Elizebeth Smith Friedman

Elizebeth Smith (1892-1980) was one of ten children born into an Indiana Quaker family. She attended Wooster College (Ohio) but transferred to Hillsdale College (Michigan) in 1913. Elizebeth joined the Pi Beta Phi (“Pi Phi”) sorority and graduated in 1915 with a degree in English literature (a favorite author was Shakespeare). After moving back to her parent’s home and a stint in the public-school system, Elizebeth was asked to join Riverbank Laboratories which was owned by Colonel George Fabyan (1867-1936). It seems the Colonel Fabyan and Elizebeth shared a common interest in Shakespeare and he wanted her to help prove his theory that Sir Francis Bacon had written Shakespeare’s plays. Read More Unit 387 & Hillsdale College