I always enjoy returning to a subject that connects us to my forthcoming book Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? A Walking Tour of Nazi Occupied Paris (1940−1944). Today, you will meet someone who was born during the latter part of the 19th-century. The men and women born just before the dawn of the 20th-century were an interesting group. They were heavily influenced by three principal world events: World War I, the Bolshevik/Russian Revolution, and the Great Depression. No one was influenced more than the first and only American who became mayor of Paris: William Christian Bullitt Jr. (1891−1967).

Did You Know?

On 14 June 1940 as the Wehrmacht marched triumphantly into Paris and turned down the Avenue des Champs-Elysées, a young German officer watched in disgust. Later, Count Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg relayed his feelings to General Franz Halder. The 33-year-old officer told the general and others that Hitler deserved to die. He was advised to keep his feelings to himself because as long as Hitler’s military victories continued, Germans would never support a coup. Four years later on the morning of 20 July 1944, Stauffenberg tried unsuccessfully to assassinate the Führer. He and many of the other ring leaders were captured, tortured, and executed for their part in the plot. The initial planning of the operation took place years earlier in Paris at the Hôtel Continental. It is one of the stops in first volume of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?

William C. Bullitt

Despite being born in Philadelphia to a very rich and pedigreed family (his ancestors included Patrick Henry and Pocahontas), Bullitt grew up in Europe. He was fluent in French and German. His maternal side was German and Jewish and his mother spoke French at home. After graduating from Yale University (and dropping out of law school after his father died), Bullitt became a correspondent for the Philadelphia Public Ledger and covered World War I events in Russia, Germany, Austria, and France. After the United States entered the war, Bullitt worked for the State Department and their intelligence service where he was noticed by President Woodrow Wilson. He was picked by Wilson to attend the 1918 Paris Peace Commission but subsequently resigned in protest over the terms of the Treaty of Versailles (his testimony before Congress helped defeat the treaty).

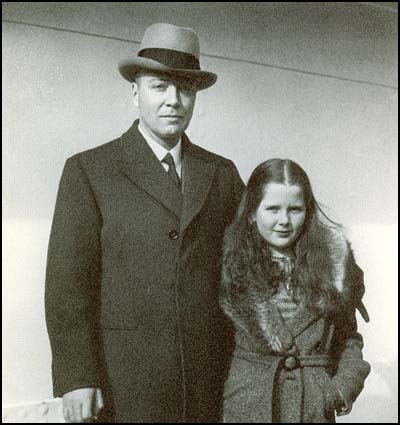

Bullitt’s second wife, Louise Bryant (1885−1936), was a journalist who wrote Six Red Months in Russia. She had been married to the radical journalist John Reed until his death in 1920. Bullitt had been good friends with Reed and in 1924, married Reed’s widow. Their marriage lasted only six years before he filed for divorce—he alleged his wife was having an affair with another woman. Bullitt gained custody of their only child, Ann (1924−2007). The story of Louise and John Reed is told in Warren Beatty’s 1981 movie Reds.

Bullitt became close friends with Franklin Delano Roosevelt and when Roosevelt became president in 1933, Bullitt was named as the first ambassador to the Soviet Union (Watch William Bullitt arrive in Moscow here.) During Wilson’s administration, Bullitt had gone on a special mission to negotiate diplomatic relations between the United States and the new Bolshevik regime. Roosevelt felt that Bullitt had made a favorable impression on the Bolshevik leaders to the point where they would accept him as ambassador. Despite his initial support of the revolution and the Soviet Union, Bullitt became disenchanted with Stalin and his government (Watch Bullitt’s speech here.) He remained ambassador until 1936 when Roosevelt brought him back and assigned Bullitt to France as ambassador. Read More The American Mayor of Paris