The Germans marched into the open city of Paris during the early morning hours on 14 June 1940. By the end of the day, almost all of the ranking Nazi officers, their troops, and administrative departments were entrenched in Paris buildings appropriated from the governments of France and other countries, French citizen’s private residences, and properties owned by French Jews. It was almost as if the Nazis knew in advance where each of them would set up shop and live during the Occupation of Paris. It was clearly a model of German efficiency. That is, except for a member of the French Resistance who ultimately chose an apartment next to the living quarters of one of the top Nazi spies in Paris. Was this a coincidence, an accident, or something planned?

Our Paris Trip

Sandy and I are back from Paris and exhausted (but in far better physical shape than when we arrived). The final numbers are in and we walked an average of 10.4 miles per day and Sandy snapped 1,868 photos. We followed all nine walks of the two volumes of our new book, Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? I don’t want to spill the beans but the Gestapo had offices all over the city. Our friend, Raphaëlle, introduced us to many interesting people, some of whom have dedicated their lives to preserving the memory of the Holocaust and Nazi crimes.

I first ran across the name of Henri Déricourt during my research into the British run spy organization called Special Operations Executive (SOE). Several of my prior blogs were about the women agents working for F Section (i.e., France) of the SOE and individual SOE agents (e.g., Nancy Wake). At the time, I didn’t really dig into Déricourt’s involvement with the SOE. However, I recently ran across a short story (“The Spy Who Chose the Wrong House”) about how he came to live next door to the Nazi officer whose job it was to capture foreign agents and French Resistance members (e.g., Déricourt). The author ends the story by mentioning what a “weird happenstance” it was that this occurred—or was it? Read more about the SOE.

Let’s Meet Henri Déricourt

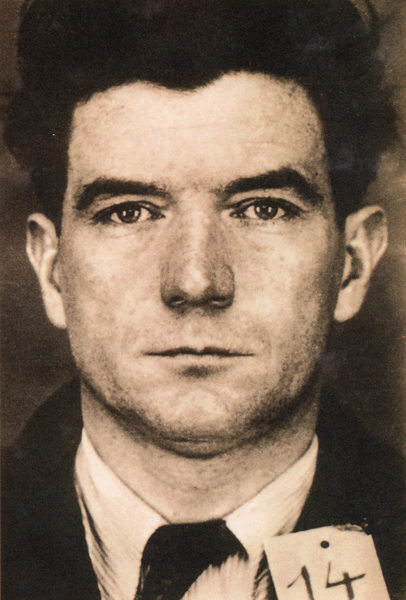

Henri Déricourt (1909−1962) was a French citizen who as an adult became a trick aviator working for the French Air Force as a test pilot and later a commercial pilot. However, it would be his exploits in 1943 and 1944 as a member of the French Resistance that earned him his infamous reputation.

SOE Recruitment

Déricourt managed to get to England in the summer of 1942 where he was investigated by MI5 or the Security Service division of Britain’s intelligence service (akin to the CIA). The MI5 agents in charge of his case were skeptical of Déricourt and his trustworthiness. Yet, he was subsequently turned over to MI6 (Secret Intelligence Service—you know, James Bond) which despite its concerns, recruited Déricourt as one of their agents. By early 1943, Déricourt was passed on once again but this time to Maurice Buckmaster (1902−1992), head of F Section for SOE who enthusiastically recruited Déricourt as an undercover agent. Read More Double Agent or Bad Neighbor