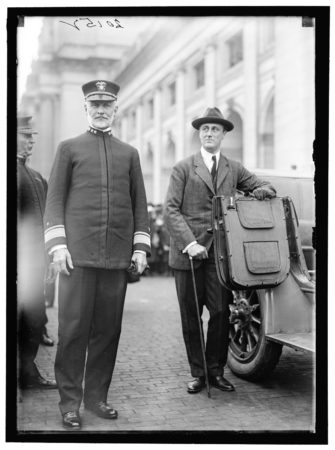

During the Wilson presidency, thirty-one-year-old Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) was appointed assistant secretary of the navy. As the second most powerful person in the navy, Roosevelt was responsible for civilian personnel, administration of naval bases, and the operations and contracting at the shipyards. It was in the context of these responsibilities that FDR first met young Joseph P. Kennedy Sr.

Kennedy Sr. was the assistant manager at the Fore River Shipyard in Massachusetts. Under his control were two Argentinian-built battleships. In early 1917, FDR summoned Kennedy to his Washington, D.C. office. Roosevelt told Kennedy he needed the two ships immediately and wanted them released on credit. Kennedy refused to turn the ships over to FDR until they were fully paid for. Standing up and putting his arm around Joe’s shoulders, Roosevelt gently informed the assistant manager that if the ships were not released immediately, he would take them using the government’s power of expropriation. Kennedy returned to Massachusetts and did not think about Roosevelt’s threat until one week later when tugboats sailed up the river to the docks. Carrying armed United States soldiers, the tugs seized the two ships.

Despite a certain measure of respect, the two men never trusted one another from that point onward. However, over the next twenty-four years, Roosevelt and Kennedy would remain loyal but use each other for political purposes.

Did You Know?

Did you know that up until 19 September 2021, the Netherlands did not have a national memorial monument honoring the victims of the Nazis? Sure, various cities, towns, and communities (e.g., The Hague Jewish Monument) had monuments honoring their citizens who were murdered by the Nazis, but a national memorial was never erected honoring all Dutch victims.

The first national memorial was officially unveiled in Amsterdam on 19 September 2021 in the heart of the historic Jewish Quarter and near the former concert hall where Jews were held prior to being sent to transit camps (e.g., Westerbork) and then to KZ Auschwitz II-Birkenau, Sobibór, Theresienstadt, and Bergen-Belsen extermination camps. During the German occupation, about one hundred trains departed from the transit camps carrying more than 102,000 Jews, Roma (gypsies), and Sinti (Romani). If you count the deaths in the Netherlands attributed to escape attempts, forced labor, and suicides, an additional 104,000 Dutch citizens perished (this does not count the more than twenty thousand who died of starvation during the winter of 1944-45). Only five thousand people survived deportation (none of the deported children returned).

There were 140,000 Jews living in the Netherlands at the outbreak of war. Amsterdam’s Jewish population was 75,000 while the Hague had the second highest Jewish population of 17,000. Approximately 75% Dutch Jews were murdered, a higher percentage than any other occupied country. (Twenty-five percent or 75,000 of France’s Jewish population were deported to the extermination camps.) The name of every Dutch victim is inscribed on a brick and the memorial is laid out with walls shaped, when seen from above, to form four Hebrew letters spelling out a word that translates to “In Memory Of.”

The architect and designer, Daniel Libeskind, said “It’s a warning to us all what can happen in so-called civilized societies.”

Joseph P. Kennedy Sr.

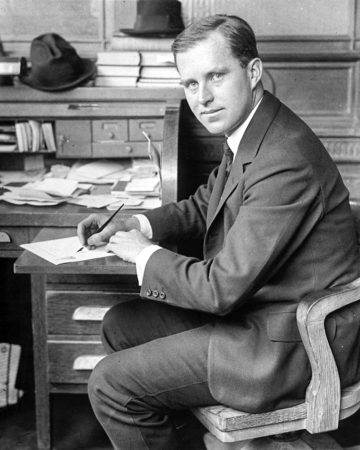

Joseph Patrick Kennedy Sr. (1888−1969) was the patriarch of the Boston Irish American Kennedy family. Married to Rose Fitzgerald (1890−1995) in 1914, the couple had nine children. Kennedy was an extremely ambitious person in business, politics, and his personal life. Most of us are aware of his behind-the-scenes political maneuvering of his four sons: Joe Jr., John, Robert (Bobby), and Edward (Ted). He earmarked his eldest and namesake son, Joe Jr., to be president of the United States. Joe Jr. (1915−1944) was a Navy pilot when he volunteered for Operation Aphrodite. On 12 August 1944, his converted B-24 prematurely exploded killing Joe Jr. and his co-pilot instantly. His father immediately transferred presidential expectations to the next eldest son, John F. Kennedy (1917−1963) and in 1960, JFK was elected as the thirty-fifth president of the United States. (Kennedy Sr. told JFK, “I’ll help finance your campaign, but I won’t pay for a landslide.”) Bobby Kennedy (1925−1968) became attorney general under his brother’s administration, the junior senator from New York and finally, the leading contender for the 1968 Democratic party presidential nominee. Ted (1932−2009) served as a U.S. senator for almost forty-seven years.

Joe Kennedy became a very rich man at an early age. He was in his mid-twenties when he invested in commodities and the stock market. After making his fortune, Joe moved into real estate and other business ventures where he made even more money. He could never be considered a true entrepreneur as he never started a business; he bought and sold existing business entities. Joe had a knack for timing his business acquisitions and sales to maximize his profits. By 1914, Joe had become America’s youngest bank president. Five years later, he joined a prominent stock brokerage firm where he used tactics that today would be against the law: insider trading, bribery, and market manipulation through dissemination of fake information. Following the market crash in 1929, Kennedy became a multi-millionaire by “shorting” stocks. As the country fell into the Great Depression, Joe took much of his money and invested in real estate. Throughout the 1920s and into the early 1930s, Joe’s business activities included sojourns into Hollywood, liquor importation, and the purchase of marquis real estate properties (e.g., Chicago’s Merchandise Mart). It has been speculated that Kennedy was a partner with the Mafia during the prohibition era. (Most of Joe Kennedy’s historical documents are held by the JFK Library and very few historians are granted access.)

Roosevelt became governor of New York in 1929 and by 1932 decided to run for president. Kennedy Sr. immediately hopped on board the FDR tsunami.

Government Appointments

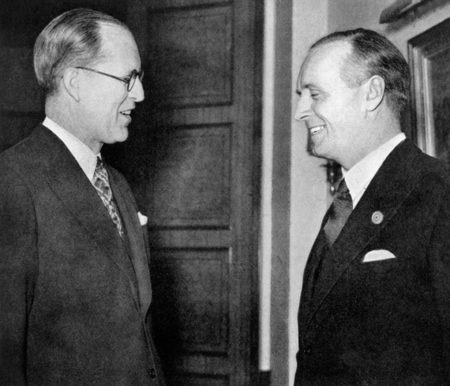

Traveling with FDR throughout New England while campaigning against President Herbert Hoover, Joe made the decision that his political future depended on FDR as a mentor. He donated a considerable sum of money to FDR’s first presidential campaign in 1932 and ultimately, it paid off.

In response to the 1929 market crash and clear market manipulations, release of false information, and lack of financial oversight, Congress created the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 1934. FDR appointed Joe Kennedy as the first SEC chairman. I suppose it was like putting “the fox in the hen house,” or as FDR put it, “set a thief to catch a thief.” Remarkably, Kennedy Sr. did a good job and bi-partisan praise for his reforms was widespread. He resigned in 1935 to take over as chairman of the U.S. Maritime Commission.

Isolationist America

After World War I and up until Hitler’s invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, America was staunchly isolationist. FDR knew that when he became president, he would have to stick to domestic and economic issues. Politically he could not mention foreign events let alone outline any plans to assist other nations. During the 1930s, FDR signed three Neutrality Acts (1935, 36, and 37) that prevented America from waging war with a foreign country as well as prohibiting support in the form of direct economic and military assistance. As Hitler came to power in 1933 and began rearming Germany, FDR kept an eye on Europe and specifically, Germany and Italy. He stayed in close touch with his ambassadors in England, Germany, and Italy.

One of the most outspoken and prominent public isolationists was Father Charles Coughlin (1891−1979). He produced a weekly radio program featuring discussions that were anti-Communist, anti-Semitic, nationalistic, and isolationist. FDR broke with his former friend and Coughlin began to attack FDR and his government programs. As a fellow Irish-Catholic, Kennedy Sr. was sent to try and get Coughlin to tone down his rhetoric but was not successful until he got the Vatican to intervene and shut down Coughlin. Joe and Father Coughlin were actually very close, and Coughlin believed his good friend to be a “shining star among the dim ‘knights’ in the (Roosevelt) administration.” Another prominent public figure (and friend of Joe Kennedy) to play an isolationist role during the pre-war years was the famed aviator, Charles Lindbergh (1902−1974).

After Hitler invaded Poland, Americans began to wake up to the worsening situation in Europe. FDR began to redirect his public comments away from domestic issues to focus on foreign events and the need for America to confront its international obligations. Circumventing the Neutrality Act, the president initiated the Lend-Lease program to support Great Britain.

Court of St. James

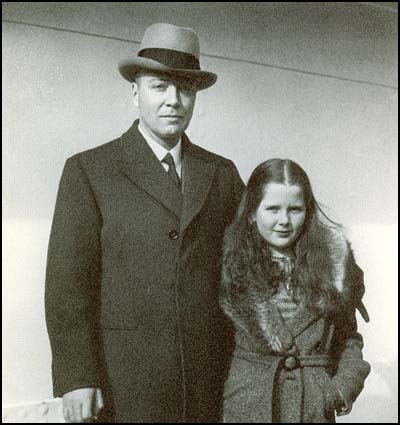

Roosevelt was well aware of Joe Kennedy’s political aspirations, including the presidency. (Kennedy wanted to be the first Catholic president.) FDR viewed Joe as someone who could potentially be a source of trouble for him in the future. So, FDR decided to get his adversary out of Washington and offered Kennedy the ambassadorship to Ireland which Joe turned down. However, after intense lobbying by Joe, FDR appointed him in 1938 as the ambassador to the Court of St. James (Great Britain). Kennedy was an Irish-Catholic in a Protestant country, and he had no experience in foreign affairs. On top of this, Joe was a staunch isolationist, admired Hitler, and thought Britain would lose if Germany started a European war (and he made sure everyone knew where he stood). Kennedy was also very confident that Roosevelt would not run for re-election in 1940 and he could step in as a viable Democratic presidential candidate.

Joe made some critical mistakes as ambassador. When the blitz began, he moved his family out of London to the countryside. It prompted Randolph Churchill to say, “I thought my daffodils were yellow until I met Joe Kennedy.” The American ambassador was all in favor of appeasement and he admired Neville Chamberlin, the British prime minister. (Kennedy was against America going to war.) This did not sit well with the future prime minister, Winston Churchill. The ambassador also talked too much, said things that were not cleared by the state department, and as time went on, his statements convinced King George VI that the American ambassador was a defeatist. Eventually, Joe was excluded from most of the high-level discussions within the British government.

As Kennedy’s public and private quotes made it back to Washington, FDR became increasingly frustrated with his ambassador. It was clear that Joe was out of step with the state department and the president’s policies, and he was recalled to Washington. However, FDR needed Kennedy’s help to attract the Catholic vote for his 1940 re-election campaign. After FDR was elected to a third term in 1940, Kennedy resigned as ambassador to Great Britain. Kennedy sat out World War II on the sidelines and while offering his assistance, the Democratic party didn’t want any part of Joe any longer⏤they didn’t trust him.

Interwar Ambassadors

The other important pre-war ambassadors who provided FDR with critical information on European events were William Bullitt, ambassador to France (1936−1940), William Dodd, ambassador to Germany (1933−1937), and Breckinridge Long, ambassador to Italy (1933−1936).

William Bullitt (1891−1967) grew up in Europe and was fluent in French and German. He was a close friend of FDR who appointed Bullitt as the first ambassador to the Soviet Union. FDR recalled Bullitt in 1936 and appointed him as ambassador to France. As the U.S. ambassador to the French Third Republic, Bullitt was a tireless negotiator for American interests in Europe and he supported France in Washington. In addition to being considered a savvy and seasoned diplomat, Bullitt’s social reputation grew as he was charming, charismatic, and hosted large, elegant parties. (He was referred to as the “Champagne ambassador.”) French politicians such as prime ministers Léon Blum and Édouard Daladier, liked him, trusted him, and confided in him. The American ambassador was invited to sit in on most of the French cabinet meetings. Bullitt was in touch almost every day with FDR by phone or correspondence badgering the president to support France with military aid after watching Hitler rearm and begin his land grab through appeasement by England and France. Bullitt hated the Nazis and Hitler knew it.

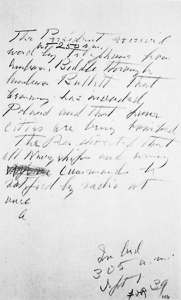

It was Bullitt’s phone call to FDR at 3:00 a.m. on 1 September 1939 that relayed the message about Hitler’s invasion of Poland. FDR wrote down the information on a note pad he always kept on the night stand next to his bed. After Hitler’s invasion and during the next eight months (commonly known as “The Phony War,” a period of no major fighting), there were few political realists left in France. Bullitt, Gen. Charles de Gaulle, and the French prime minister, Paul Reynaud knew the Germans would successfully attack France. The French believed their politicians and military leaders, all of whom expressed confidence that the Maginot Line would keep out the Germans. FDR began to ignore the daily cables from Bullitt labeling them as “too pessimistic.” While Bullitt was wrong with other observations, his prophecies about France’s fate were correct.

In May 1940, the Germans overran the low countries, bypassed the Maginot Line, and proceeded to invade France. As the Wehrmacht marched toward Paris, the French government left the city for Tours. By 10 June, the American Embassy, French military headquarters, and the Prefecture of Police remained as the only official government operating organizations in the city. Several days later, the military abandoned the city. FDR ordered his ambassador to leave the city and follow the French government. Bullitt refused and it marked the beginning of his fall-out with FDR. Reynaud declared Paris an “open city” and appointed Bullitt as the provisional mayor on 12 June (click here to read the blog, The American Mayor of Paris). Ambassador Bullitt resigned in November 1940 and returned to Washington not realizing he had fallen from grace and his national political career was over.

William Dodd (1869−1940) was appointed by FDR in 1933 to become ambassador to Germany. He showed up in Berlin about five months after Hitler came to power. Dodd immediately did not like what he saw. He was quick to realize that the Nazis were an increasing threat and he tried, unsuccessfully, to get the Germans to moderate their treatment of the Jews. Dodd hated the upper echelon Nazis so much that eventually, he refused to host any official function at the American embassy if it meant he had to invite them.

FDR had a difficult time filling the position of American ambassador to Germany. He finally settled on Dodd who was a history professor and had little if any, political experience and certainly no foreign diplomatic experience. However, by the time he got to Berlin, it didn’t take long for Dodd to assess the situation. After the “Night of the Long Knives” in June/July 1934 when Hitler violently purged the Sturmabteilung, or SA (i.e., “Brownshirts”), Dodd became even more critical of the Nazi regime. Throughout his tenure, Dodd kept his superiors in the state department apprised of the deteriorating situation and offered his predictions for the outcome. He was one of the few diplomats to accurately assess and predict Hitler’s intentions (although he was regarded as being too pessimistic). Dodd grew increasingly frustrated with the state department due to its inactions and what he perceived to be a disinterest. (In reality, America was still isolationist and politically, it would have been a disaster to address German events let alone suggest America get involved.) This led to Dodd’s decision to resign. FDR would not accept the resignation but allowed Dodd to temporarily return home for health considerations. FDR knew Dodd was right and wanted him to remain in Berlin where the president knew he could count on accurate assessments from his ambassador. Upon his return to Germany, Dodd drew up a report outlining his belief that the Europeans refused to believe that Hitler would carry out his expansionist agenda as described in the Führer’s book, Mein Kampf.

Dodd was in constant conflict with the state department, not the least of which was their opinion that Dodd was not suitable for the prestigious job because of his personal background. Kennedy and Bullitt also had their battles, but it was because Secretary of State Cordell Hull (1871−1955), and Undersecretary of State Sumner Wells (1892−1961) were angered that their two key ambassadors by-passed them and communicated directly with the president. Dodd resigned his position in 1937 and was replaced by Hugh Wilson.

As a side note, Dodd’s daughter, Martha (1908−1990), became a spy for the Soviet Union in 1936. She and her husband were convicted in absentia in 1957 of enemy espionage and soon after, the Soviet Union granted them asylum. Disillusioned by life in the Soviet Union, they left for Cuba in 1963 and in 1970, the couple moved to Portugal where Martha died twenty years later.

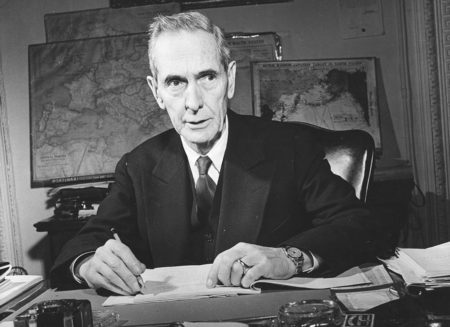

Breckinridge Long (1881−1958) was a career diplomat and ambassador to Italy. He is considered one of FDR’s worst political appointments during the president’s four terms. Long admired the Italian dictator, Mussolini, and supported Il Duce’s invasion of Ethiopia in October 1935. The ambassador predicted the European conflict, but FDR considered his good friend to be too pessimistic.

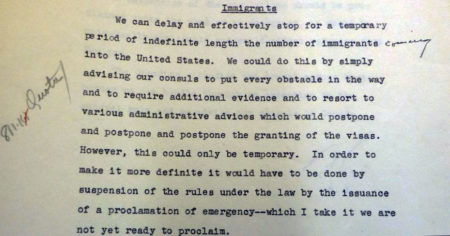

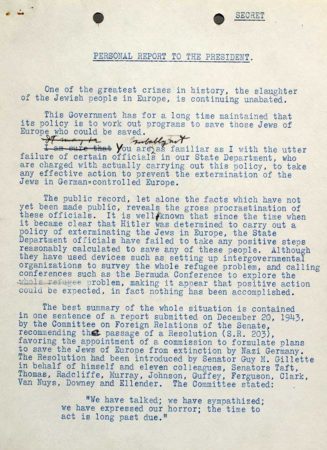

Breckinridge Long will be remembered not so much as a pre-war ambassador to Italy but as an assistant to the secretary of state after his tenure in Italy. Long oversaw immigration issues and after the fall of France, tens of thousands of refugees, a large percentage of whom were Jewish, applied for visas to enter the United States. He knew that immigration was unpopular with the American voter and it didn’t help that Long was anti-Semitic. He was responsible for turning away the refugees through coordinated processing delays, restrictions, and stall tactics. Through the efforts of Eleanor Roosevelt, Long was finally pressured to allow a certain number of children to enter the country. The rest of the unfortunate refugees were turned away and many never survived the war. Mrs. Roosevelt considered Long to be a Fascist and for the rest of her life, she regretted not being able to talk her husband into firing the former ambassador.

A Quick Note on Josephine Baker

I recently mentioned that Josephine Baker would enter the Panthéon in late November (click here to read the blog, An African American in Paris). I though you would like to view a short video of the ceremony. Click here to watch the video.

★ Learn More About FDR and His Wartime Ambassadors ★

Brownell, Will and Richard N. Billings. So Close to Greatness: A Biography of William C. Bullitt. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1987.

Etkind, Alexander. Roads Not Taken: An Intellectual Biography of William C. Bullitt. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017.

Goodwin, Doris Kearns. The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys: An American Saga. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987.

Kross, Peter. Joseph P. Kennedy: Most Controversial Ambassador to Great Britain? Warfare History Network. Click here to visit the warfare history network web-site.

McKean, David. Watching Darkness Fall: FDR, His Ambassadors, and the Rise of Adolf Hitler. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2021.

Nasaw, David. The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy. London: Penguin Press, 2012.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

From Sandy and I, we wish a HAPPY NEW YEAR to everyone! Welcome to 2022. ![]()

After the last two years, I’m not sure what to expect in the new year. I thought we’d be back on the high seas visiting ports around the world. Well, that didn’t happen as our first two trips of the year (Japan and Russia) have now been cancelled. I suspect it won’t be until 2023 that we will have a chance for international travel. The biggest problem I have is that things keep changing from day-to-day and it’s tough to plan with such uncertainty. As many of you know, it costs a lot of money to travel and frankly, to be forced to wear a mask all the time isn’t worth it (in our opinion).

As I write this, we are struggling with getting the new book printed. The binding doesn’t quite meet our high standards or that of Pollock Printing. As I’ve pointed out before, the book is thicker than prior ones and we had to use 80-pound paper (as opposed to 70-pound paper in the past). Both issues contribute to the binding issues we are experiencing. Hopefully by the time you read this, Alex Pollock and I will have come up with a solution. You can be assured that we will not sacrifice quality just to meet a self-imposed deadline.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Carl S. for contacting us regarding our recent blog, Salon Kitty (click here to read). Carl’s father moved from Germany to America around 1922. His father came from a large family and the oldest brother was named Karl Schwarz. This is the same name as one of the German officers in the blog and Carl was curious if this might have been his uncle. Carl’s relatives in Germany are unwilling to discuss the war or the twelve years that Hitler was in power. Unfortunately, Karl Schwarz is a common name and there wasn’t anything I could dig up in my research on the SS officer. I did some arithmetic and determined that Carl’s uncle would have been in his mid-forties around the time Kitty’s brothel was taken over by the Gestapo. The photograph I obtained of SS-Untersturmführer Karl Schwarz reflected a man much younger than forty. So, I came to the conclusion that the Gestapo man was not related to Carl. As I told Carl, “There is always the question as to whether one really wants to know certain facts about relatives or is it best to leave to the past.”

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2022 Stew Ross