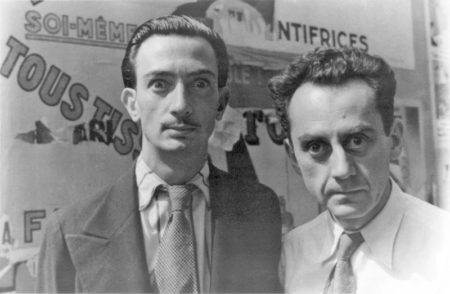

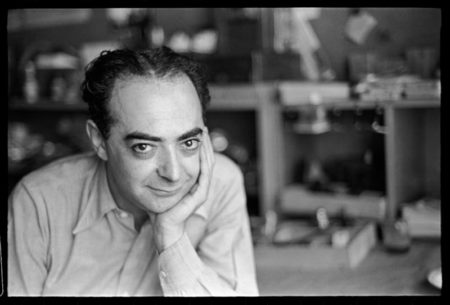

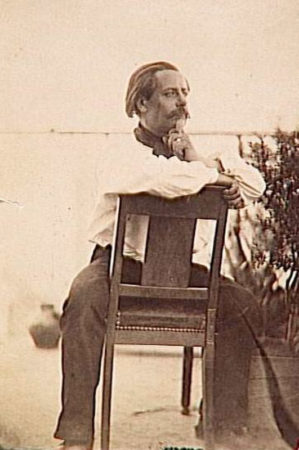

Paris is famous for its 20th-century photographers such as Brassaï (1899−1984), Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908−2004), and Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894−1986). The city also produced two well-known celebrity photographers: Man Ray (1890−1976) and Felix Nadar (1820−1910) ⏤ Click here to read the blog, First Celebrity Photographer. During the mid-19th-century when photography was in its infancy, a group of photographers were hired by the city’s historic-works department to document Paris through their lenses. Today we are going to reintroduce you to one of those photographers, Charles Marville. While the original 2015 blog (same title) included only one image, we have expanded the story using multiple photographs. I have tried to find locations where a Marville photo can be paired with a contemporary image . . . the “before and after” effect. I like viewing these types of comparisons and thought you might also enjoy it.

I’m often asked how and why I started writing the walking tour books and subsequently, the blogs. Well, around 2010, I ran across a book by Leonard Pitt called Walks Through Lost Paris (refer to the recommended reading section below). Mr. Pitt takes the reader on four walks through historic Paris and presents pre-Haussmann photographs side-by-side with contemporary shots. The reader can easily see how Paris was transformed in the mid-1800s from a medieval city to the modern city we enjoy today. Sandy and I took Mr. Pitt’s book with us to Paris, and I became determined to write a similar book but based on the French Revolution. My one-book idea blossomed into five published books with three or four more to come.

Mr. Pitt’s book introduced me to several photographers, including Marville, who were hired by the city to visually record Paris before Haussmann began ripping it apart (click here to read the blog, The Destruction of Paris and here to read the The Missing Emperor). These photographs were “discovered” in the 1980s and have been used extensively in books and exhibitions around the world. Sarah Kennel’s book, Charles Marville: Photographer of Paris, was written in conjunction with an exhibition coordinated by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (again, refer to the recommended reading section below). It’s a beautiful book and I recommend it to anyone with an interest in historic Paris. From these images and old maps such as the 1550 Plan de Truschet and Hoyau, we are able to get a sense of what medieval Paris looked like. London was able to shed its medieval cloak after 1666 but it took Paris another two hundred years for its transformation.

When we first started going to Paris, I was not much into the “medieval” period. The Musée de Cluny, or musée national du Moyen Âge Paris (National Museum of Middle Ages) was not high on our list of stops. I gained a healthy interest in medieval Europe as I researched the history of Paris for our third and fourth books, Where Did They Burn the Last Grand Master of the Knights Templar (click here to read the blog, Cour des Miracles and here to read Hanging Around Medieval Paris). Even if you’re not into medieval times, I think you’ll find the images in this blog interesting. Read More Charles Marville and le Vieux Paris