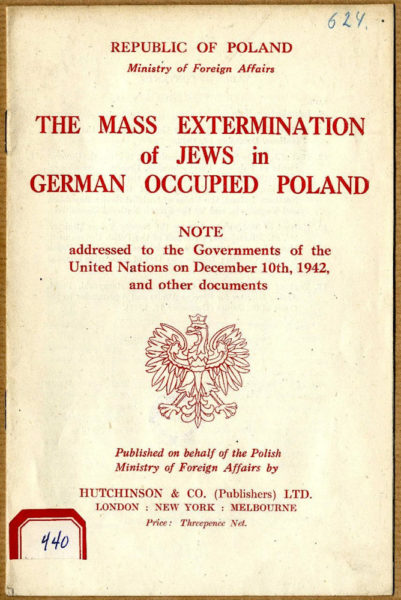

There is a 2002 film that is based on the memoirs of a Polish-Jewish pianist who barely escaped (twice) deportation to KZ Treblinka, survived the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, and the razing of Warsaw in late 1944 by the Germans as they retaliated against an uprising by the Polish home guard.

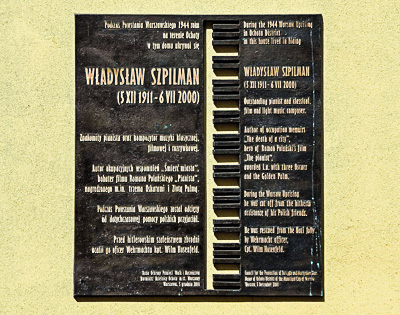

The film is called The Pianist and stars Adrien Brody as Władysław Szpilman, the Jewish pianist. It was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won three: Best Director (Roman Polanski), Best Actor (Brody), and Best Adapted Screenplay (Ronald Harwood).

I’ve never seen the film. I don’t watch movies. I would prefer to see a well-researched documentary that is true to the historical facts. However, it is my understanding from reading various reviews, the movie pretty much sticks to the true story of Władysław Szpilman without the usual Hollywood historical distortions. Perhaps after I have completed and published this blog, I might change my mind about watching The Pianist.

After the war, most of the Holocaust survivors asked the question, “Why me? Why did I survive when millions did not?” I’m certain Mr. Szpilman asked himself that question many times as he was the sole survivor of his family. As his memoirs point out, he experienced many lucky breaks during those five horrible years in Warsaw. But one lucky experience stands out in particular. It was the effort by a German Wehrmacht captain to shelter Mr. Szpilman and protect the pianist from certain death.

I invite you to read several of our previous blogs that focused on the 1943 Warsaw Uprising (Nazi Frankenstein [click here to read] and Ghetto Girls [and here to read]).

Errare humanum est, sed perseverare diabolicum

(“To err is human, but to persist in error is diabolical”)

⏤ Larry Stern’s sixth-grade Latin teacher

Did You Know?

Did you know that France is drowning in ACRONYMS? A recent article calls them “cradle-to-grave acronyms” that are now “an inescapable feature of life in France.”

First through fifth elementary school grades are referred to as CP, CE1, CE2, CM1, and CM2. Earning a minimum wage? If so, it’s called the SMIC. If you start a new small business, then you’ve opened a TPE. Selling your mansion? You will pay the IFI tax. Many French senior citizens live in an EHPAD, or nursing home. Army officers are trained in the CNFCSTAGN. French workers are classified as CDI or CDD (a work contract of unlimited duration or temporary contract, respectively). We all know France has a 35-hour work week. If you go beyond the 35-hours, you are entitled to RTT, or offsetting vacation time. If you are poor and qualify for government subsidiaries, you are known as RSA, APL, and PA. Lastly, France’s consumer protection agency is referred to as DGCCRF.

Even President Macron bemoans the acronym crisis. He is trying to simplify the acronym bureaucracy. His government is ordering officials to “Speak French to us.” The United States government certainly has its issues with acronyms as military “speak” can attest. But in France, it seems acronyms have permeated every inch of daily life.

It’s hard to understand how this situation could get so out of hand. One French expert blames the “all-encompassing government bureaucracy” and says, “It has a tentacular character.” She thinks it is a paradox due to the country’s fixation on its literary culture and preservation of the French language. In 1635, The Académie français was founded as the official authority on the usages, vocabulary, and grammar. Although this government agency has no official power, its mission is to preserve the French language and prevent the Anglicization of the language. I believe we have highlighted some examples in previous blogs.

ATM I’m working on a new blog and BTW, LMK if you like our blog topics. FWIW, I’m NGL but it’s a chore coming up with TBD stories. My favorite acronym is BOGO. Stella, our beagle, suffers from FOMO. I wrote this on Sandy’s birthday so HBD to her.

TYVM for reading our blogs.

TTYL.

Władysław Szpilman

Władysław Szpilman (1911−2000) was born in Sosnowiec, Poland. (Between 1902 and 1918, the town was considered part of the Russian Empire.) His academic studies in music took place in Warsaw and Berlin where he studied under several pupils of the famous composer, Franz Liszt. After Warsaw, Mr. Szpilman was accepted to the Berlin Academy of Arts. When Hitler came to power in 1933, Mr. Szpilman moved back to Warsaw where he became a celebrated pianist due to his performances on Polish Radio, concerts, and tours.

On 1 September 1939, the Germans invaded Poland and quickly occupied the country. (The Soviets followed with their invasion on 17 September.) The country was divided into two zones: German and Soviet. Hitler considered all Poles (Jewish or not) to be Untermensch and a systematic elimination of the Poles began. Poland’s resistance to German occupation was embodied in three organizations of which the Armia Krajowa, or “Home Army” was the largest and most effective.

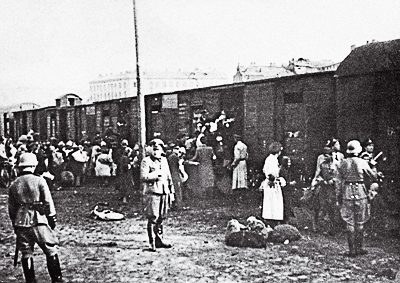

Hitler appointed Hans Frank (1900−1946) as Governor-General of the occupied Polish territories. Almost immediately, anti-Jewish laws were enacted, and Frank began a reign of terror. By January 1942, the Nazis had finalized their “Final Solution” plans to exterminate the Jews living in Germany and the occupied countries. Along with other concentration camps, three camps were built in Poland for the single purpose of murdering Jews and others. They were KZ Treblinka II, KZ Majdanek, and KZ Auschwitz II-Birkenau. Under Frank’s 4-year jurisdiction, more than four million people were murdered. (During the summer of 1942, 254,000 Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto were deported to KZ Treblinka where they were killed.) Frank was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity by the Nuremberg Military Tribunal and he was hanged on 16 October 1946.

Mr. Szpilman and his family (mother, father, brother, and two sisters) were forced to move into the Warsaw Ghetto upon its establishment in November 1940. He initially found work playing in various cafes. However, by the summer of 1942, the ghetto’s residents were being rounded up for deportation and ultimately, extermination.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Warsaw Uprising

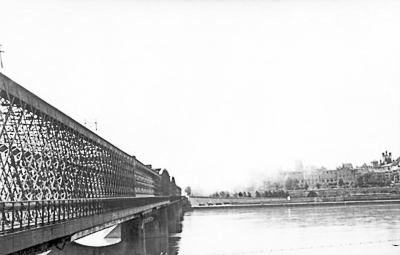

There were two distinct uprisings in Warsaw. The first was the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising that occurred between 19 April and 16 May 1943 when Jewish occupants of the ghetto began to resist the deportation efforts of the Germans. The second is known as the Warsaw Uprising and it took place between 1 August and 2 October 1944. The uprising was led by the Polish Home Army and the timing coincided with the German retreat from Poland in advance of the approaching Soviet army from the east. After the 1943 uprising, the ghetto was destroyed by SS-Gruppenführer Jürgen Stroop’s troops and after the 1944 uprising, the city was leveled by the Germans as Soviet troops watched from across the Vistula River.

The Warsaw Ghetto

The establishment of the Warsaw Ghetto was announced by Hans Frank on 16 October 1940 and more than 400,000 Jews were required to live within the 1.3 square mile area surrounded by a ten-foot-high wall topped with barbed wire. It became the largest ghetto in any of the Nazi-occupied countries. The actual size of the ghetto decreased over time as the population declined due to deportations, executions, and death through disease or starvation along with the eventual destruction of the ghetto by the SS troops.

By October 1942, Mordechai Anielewicz (1919-1943) had organized the underground Jewish Combat Organization to fight the Nazis against any further deportations. By then it was clear to the residents of the ghetto that Jews were being sent to their immediate deaths rather than “relocation” as the Nazis told them. The resistance began to collect weapons, ammunition, and supplies. On 18 January 1943, the Germans began the next wave of roundups in the ghetto. This time when the SS marched into the ghetto, they were met with bullets and Molotov cocktails. Three months later, all-out war broke out between the ghetto occupants and the Nazis.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

Jewish resistance fighters entered bunkers, built command/fighting posts, and began executing Jewish collaborators. Attempts by the Nazi commander, SS-Brigadefúhrer Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankenegg (1897-1944), to control the situation failed. He was considered unfit to liquidate the Jewish ghetto and the head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler (1900−1945), removed von Sammern-Frankenegg and reassigned him to Croatia where he died in combat.

On 17 April 1943, SS-Gruppenführer Jürgen Stroop (1895−1952) replaced von Sammern-Frankenegg and two days later, ordered two thousand SS men to enter the ghetto for the purpose of rounding up the Jews for deportation to the extermination camps. It was called the Grossaktion or, “Great Operation” and it represented the final major battle of the uprising. The Nazis were attacked by 750 resistance fighters and the SS suffered many casualties which resulted in Stroop ordering a retreat. He then ordered the ghetto’s buildings to be destroyed by fire. As the fires spread, the ghetto occupants emerged from hiding and were either executed on the spot or rounded up and deported to KZ Treblinka. Although the resistance fighters continued to fight, by 28 April most of the fighting had ended. On 8 May, the last fortified bunker was cleared by the Nazis using poison gas. (The term “bunker” was used by the Germans for the fortified cellars in the ghetto’s residential buildings.) On 16 May, the fighting stopped, and Stroop pushed the detonation button to blow up the Warsaw synagogue. Destroying the synagogue and leveling the ghetto was Stroop’s message to his superiors and the world that he had won.

When it was all over, 56,065 Jews had been flushed out and caught. Twenty-five percent of them were immediately executed by Stroop’s troops while six thousand perished in the shelling or fire. The rest were deported. Only about one hundred Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto survived the war. Three hundred Germans were killed during the uprising.

Click here to watch the video “5 to Live and Die with Honor:The Story of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising:

SS-Gruppenführer Jürgen Stroop

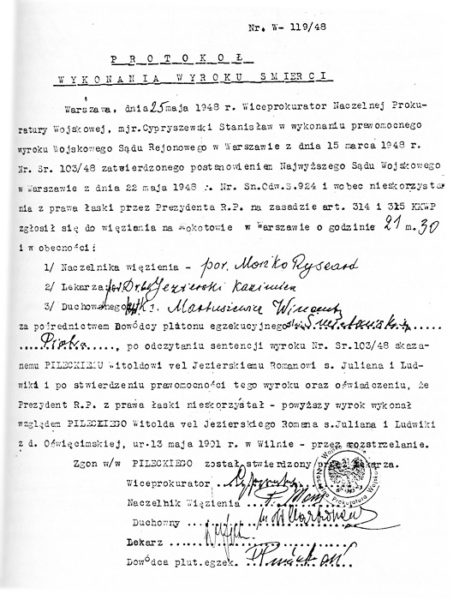

Stroop surrendered to the Allies on 10 May 1945. He was tried at the Dachau Trials and found guilty and sentenced to death. However, Stroop was extradited to Warsaw and his death sentence was postponed. He was tried at the Warsaw Criminal District and the outcome was the same: death by hanging. This time, Stroop did not escape his sentence, and he was hanged on 6 March 1952 at Mokotów Prison.

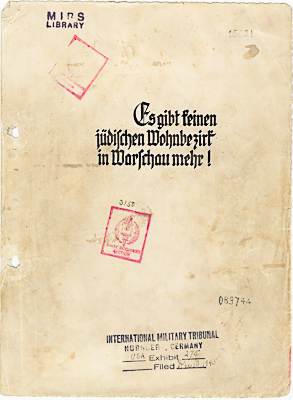

One of Stroop’s legacies was the report formally called Es gibt keinen jüdischen Wohnbezirk in Warschau mehr, or “There is no Jewish residential district in Warsaw anymore.” The report was ordered by the SS chief for Poland, and he intended it to be a gift to Heinrich Himmler. This project was assigned to Stroop, and it is a 125-page account of the destruction of Warsaw and the deportations of its residents. Fifty-three photographs are included in the report.

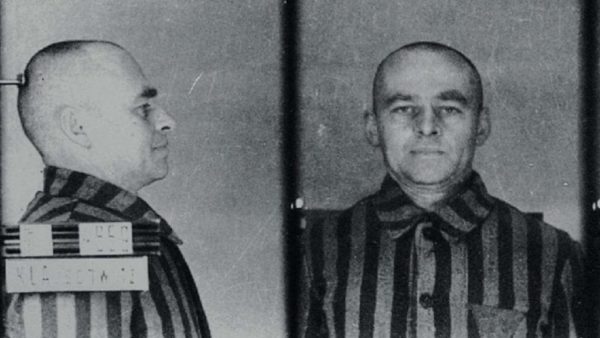

Wilhelm Hosenfeld

Wilhelm “Wim” Hosenfeld (1895−1952) was born in Fulda, Germany, a town about 103 km, or 64 miles to the northeast of Frankfurt am Main. He served in World War I and was severely wounded. After the war, Hosenfeld married and became a schoolteacher. He was heavily influenced by the Catholic Church, his wife’s pacifist views, and a strong sense of German patriotism.

Hosenfeld was drafted into the German Wehrmacht in 1939 and stationed in Poland for the entire war until his arrest on 17 January 1945 by the Soviets. He had joined the Nazi party in 1935 but as time went by, grew disgusted with Nazi policies and their treatment of Jews, Poles, and other groups of people the Nazis deemed undesirable.

https://www.yadvashem.org/press-release/16-February-2009-11-22.

Hauptmann (Captain) Hosenfeld’s assignments included running a POW camp, sports and culture officer, and staff officer for the Wehrmacht Wachschau (Warsaw Guard Regiment). During his Warsaw duty, Hosenfeld befriended the Poles, attended Mass, and even tried to learn the Polish language. It was during this period of time that he began to give refuge to people the Nazis had targeted for extermination.

The Robinson Crusoes of Warsaw or “Warsaw Robinsons”

The terms “Robinson Crusoes of Warsaw” or “Warsaw Robinsons” were given to the Poles who survived the 1944 Warsaw Uprising and subsequent destruction of Warsaw. They hid in the ruins of Warsaw for as long as three and a half months until Soviet troops entered the city on 17 January 1945.

The exact number of people who went into hiding is not known but estimates range between a few hundred and several thousand. What is known is that very few actually survived to see liberation. One of the most famous “Robinsons” was Władysław Szpilman.

Survival

Mr. Szpilman’s entire family was deported to KZ Treblinka in August 1942. A lucky break occurred when a Jewish policeman recognized Władysław and pulled him from the line waiting to board the cattle rail car at the Umschlagplatz (assembly area). After this, Mr. Szpilman worked as a laborer in the ghetto and helped smuggle arms and ammunition for the resistance. One of his jobs allowed him to exit the ghetto each day and afforded him the opportunity to find food. By February 1943, Mr. Szpilman arranged for a hiding place outside the ghetto. This was the first of many hiding places when the fear of capture and deportation was so acute that he contemplated suicide several times.

When the Warsaw Uprising began, Mr. Szpilman was hiding in a building the Germans targeted for destruction. He survived tank attacks and the resultant fire. Escaping the heavily damaged building, Mr. Szpilman moved around the city until the end of August when he moved back to his former building albeit burnt and a shell. Food and water were difficult to find but he managed to survive despite very little protection from the elements. By November, Mr. Szpilman had moved to an attic in another building, but his accommodations did not protect him from the extreme cold. At great risk, he went from room to room looking for a working stove. He found one and while trying to light it, a German soldier discovered Władysław.

The soldier left and Mr. Szpilman returned to the attic where he hid. The German returned shortly with other soldiers, but they eventually left after not being able to find Mr. Szpilman. He was eventually seen by two German soldiers who began shooting at him. The Polish pianist escaped and found refuge in yet another multi-story building where he took up residence in the attic and began the ritual of trying to find food in the building’s apartments. One of the apartments he entered was occupied by a German officer who wanted to know what Władysław was up to. The officer was Hauptmann Wim Hosenfeld.

Hosenfeld asked Mr. Szpilman for his occupation. Upon finding out Władysław Szpilman was a professional pianist, Hosenfeld directed him to play Chopin’s Nocturne in C sharp minor. After learning Mr. Szpilman was Jewish, the Wehrmacht captain decided the pianist couldn’t leave the building. From that point on, Hosenfeld supplied Mr. Szpilman with food and water as well as keeping him up to date with the latest war news. During mid-December, Hosenfeld’s unit left Warsaw and within four weeks, the Soviet army arrived in Warsaw.

Before the German captain left, Władysław told his benefactor that if he ever needed help to ask for the pianist Szpilman of the Polish Radio.

Postwar — Władysław Szpilman

Mr. Szpilman resumed his musical career in Warsaw at Radio Poland. It took him more than five years to find out the name of the German captain who provided protection. Władysław ran into a musician friend who had met Hosenfeld in a Soviet POW camp. Hosenfeld asked the musician if he knew Szpilman of the Polish Radio. Zygmunt Lednicki, a violinist, did know Mr. Szpilman but unfortunately, never learned the German’s name. Eventually, Władysław was able to track down his protector’s name.

Between 1945 and 1963, Mr. Szpilman was the director of Radio Poland. He also wrote music for plays and films as well as performing at more than two thousand concerts.

Postwar — Wim Hosenfeld

After the war, Wim Hosenfeld was captured by the Soviets and put on trial as a war criminal. (They believed he was a member of the Sicherheitsdienst, the Nazi party intelligence organization.) He was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. In 1950, his sentence was commuted to twenty-five years at hard labor, but two years later died in a Soviet prison. In addition to suffering a series of strokes, it is likely that his health suffered from years of torture, malnutrition, and lack of medical treatment. It is likely Hosenfeld is buried in Volograd (formerly Stalingrad) along with other German prisoners of war.

Yad Vashem — Righteous Among the Nations

Yad Vashem is Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. Its mission is to preserve the memory of Jews murdered by the Nazis and their accomplices. It collects the stories of the survivors, provides research resources on the Holocaust, and honors both Jews who fought the Nazis as well as non-Jews who saved Jewish lives. The latter bestows the title, “Righteous Among the Nations” to gentiles who took risks to help Jews during the Holocaust. Nominations can only be recommended by Jewish people and the nominee must have rendered assistance on a continuous basis without any financial gain expected.

Wim Hosenfeld was nominated several times by Mr. Szpilman’s son. Two surviving witnesses testified that Hosenfeld shielded them from the Nazis but despite acknowledging the assistance Hosenfeld gave to Messrs. Szpilman and Wurm, the Commission for the Designation of the Righteous Among the Nations refused to grant the award until Hosenfeld was cleared of any war crimes during the Warsaw Uprising.

Declassified documents, letters, and personal diaries were examined by the commission, and it was determined that Wim Hosenfeld was anti-Nazi and did not commit any war crimes. In 2009, Wilhelm Hosenfeld was accepted as Righteous Among the Nations along with more than 28,000 other individuals including Oskar Schindler.

Did the 2002 movie, The Pianist play a role in convincing the commission to bestow the honor? Possibly.

Chopin’s “Ballade No. 1 in G Minor”

Please enjoy Vladimir Horowitz as he performs Chopin’s “Ballade No. 1 in G Minor.” Click here.

Next Blog: “Doolittle’s Missing Plane No. 8”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

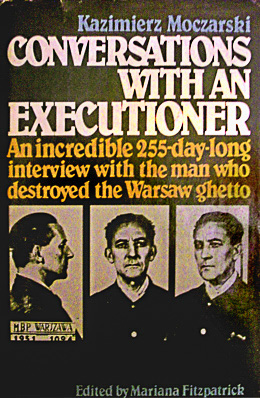

Moczarski, Kazimierz. Conversations with an Executioner. Edited by Mariana Fitzpatrick. English translation. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1981. This is a memoir of the author’s conversations with Nazi war criminal, Jürgen Stroop. The two men shared a death row cell for nine months during which Stroop explained his role in putting down the Warsaw Ghetto uprising.

Polanski, Roman (co-producer). The Pianist. Canal+, Studio Babelsberg, and StudioCanal, 2002.

Richie, Alexandra. Warsaw 1944: Hitler, Himmler, and the Warsaw Uprising. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2013.

Rotem, Simha. Edited by Barbara Harshav. Kazik: Memoirs of a Warsaw Ghetto Fighter. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

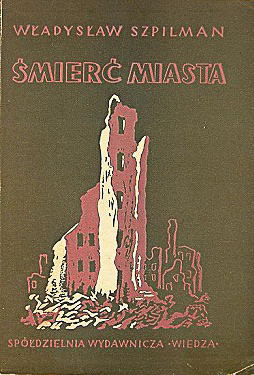

Szpilman, Władysław. Śmierć Miasta. Pamiętniki Władysława Szpilmana 1939−1945 (“Death of a City: Memoirs of Władysław Szpilman 1939−1945”). Warsaw: Wiedza, 1946. This is the original Polish book written by Szpilman. There have been several other versions as well as translations.

Szpilman, Władysław. English translation by Anthea Bell. The Pianist: The Extraordinary True Story of One Man’s Survival in Warsaw, 1939−1945. London: Picador, 1998.

Warsaw Rising Museum Click here to visit the museum web-site.

Werstein, Irving. The Uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1968.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are excited about our upcoming fall trip to Europe. We’re taking a river cruise that begins in Paris and several weeks later, we end in Warsaw, Poland. We decided to go into Paris a couple of days early so we can meet up with Raphaëlle and tour Fontainebleau. We will make time to visit the “new” Notre Dame and see the restored cathedral. I’ve read that it’s like walking into the church right after it was built in the Middle Ages.

Note: Raphaëlle is our “go-to” guide in and around Paris. If you would like an introduction to Raphaëlle, please contact me.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

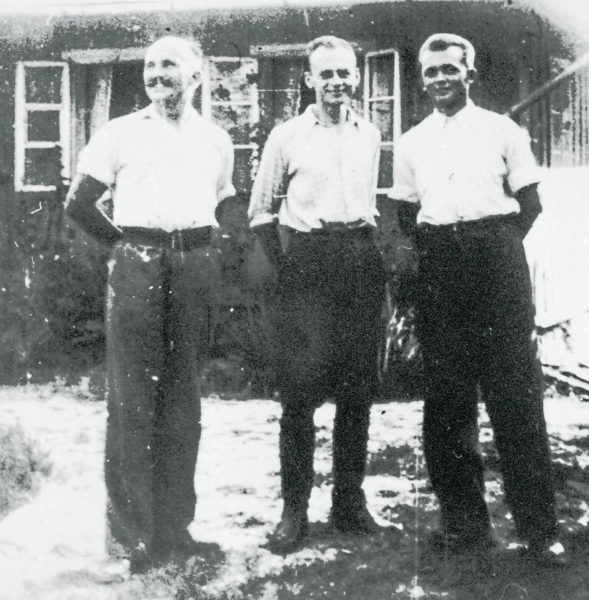

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

We heard from our good friend Carl S. almost immediately after posting the most recent blog, The Colmar Pocket (click here to read). It turns out his wife lived in a village to the east of Strasbourg and as a seven-year-old, she and her family experienced the liberation of Einvaux by American troops fighting in the Colmar Pocket. Carl was kind enough to send me several photos taken as the tanks rolled through the village. I’m very pleased to post these images for you. A big thank you to Carl for sharing part of his family’s story with us.

PLEASE REMEMBER that you can order any of my books directly from us. Your book will be personally autographed, and we will pick up the postage. Only the Kindle versions are available now through Amazon.

Stew.ross@yooperpublications.com

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please contact Stew directly for purchase of books, Kindle available on Amazon. Stew.ross@Yooperpublications.com or Contact Stew on the Home Page.

Shepherd.com is like wandering the aisles of your favorite bookstore.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf on WWII.

Check out Stew’s bookshelf on the French Revolution.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2025 Stew Ross