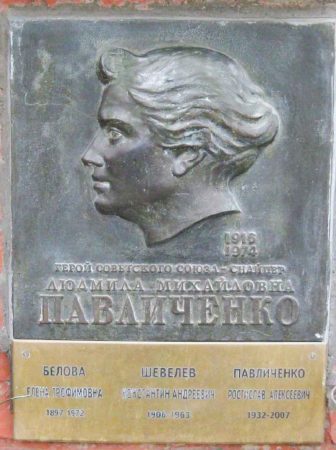

Some of you may remember one of my 2022 blogs, Lady Death (click here to read the blog). It was the story about Soviet women snipers during World War II. Today, we turn our attention to a Finnish sniper who was credited with more than five hundred kills over a period of only three and a half months during the 1939-40 “Winter War.” (That’s an average of five kills per day.) Simo Häyhä is considered one of the greatest snipers of all time and is often referred to as Valkoinen Kuolema, or “The White Death.”

I will be the guest speaker for Bonjour Paris on 6 December 2023 for a Zoom presentation to their members and others. The topic will be “Walking History: In the Footsteps of Marie Antoinette” and I will take you on a walk along the exact route in Paris that the queen’s tumbrel took to the guillotine. I invite you to join us for the discussion and slide show.

Bonjour Paris (click here to visit the web-site) is a digital website dedicated to bringing its members current news, travel tips, culture, and historical articles on Paris. I have been a member for more than ten years and have found its content to be quite interesting, practical, and entertaining.

I will have a direct link to sign up for my presentation at a later date. There is no cost to Bonjour Paris members and €10,00 for non-members. The time of the live presentation on 6 December will be 11:30 AM, east coast time.

Did You Know?

Did you know that the last known surviving “Monuments Man” passed away in July 2023? Richard M. Barancik (1924−2023) was a private first class in the United States Army and stationed in England in 1944. His unit was onboard a ship crossing the English Channel in December 1944 on its way to fight in the Battle of the Bulge. One of the ships sailing alongside was sunk by a German U-boat and Barancik’s ship was diverted from its mission. He ended up in Austria at the end of the war and volunteered for the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives unit, nicknamed “the Monuments Men and Women” (click here to read the blog, The Monuments Woman).

During the Allied march toward Germany, these men and women were responsible for tracking down and protecting art, artefacts, and architectural items from destruction. After the war, they were tasked with locating stolen artwork that the Nazis had stashed away in hidden locations. Barancik served as a guard at the Austrian salt mine where more than 6,500 works of art were stored by the Nazis. Besides serving as a guard, Pvt. Barancik drove trucks transporting the sealed crates to collection centers such as the Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point.

The experience of working with art experts was responsible for his career as an architect after the war. Studying at the University of Cambridge and the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Barancik returned to America to complete his degree at the University of Illinois. In 1950, he founded an architecture firm, Barancik, Conte & Associates, and retired from the firm in 1993. In 2015, Barancik and three other surviving members of the Monuments unit were awarded Congressional Gold Medals.

Let’s Meet Simo Häyhä

Simo Häyhä (1905−2002) was born in the tiny southern Finnish village of Kiiskinen in the Rautjärvi municipality bordering Russia. He was the seventh of eight children born into the farming family of Juho and Katriina Häyhä. Growing up as a farmer and hunter, Simo joined the Finnish White Guard, a voluntary militia, when he was seventeen.

By 1925, he completed his mandatory military service and entered Finland’s military reserve. In 1938, Simo (known to his friends as “Simuna”) was chosen to begin training as a sharpshooter in the Utti regiment. At thirty-three-years, he was one of the older men, but this did not preclude being called up in September 1939 after the Soviets invaded Poland. (Finland shares about 810 miles of its eastern border with Russia.)

“This Is Our Land and We Have to Defend It”

On 10 October 1939, Häyhä reported to the Rautjärvi White Guard and was assigned to the 6th Company of Infantry Regiment 34 (“6/JR 34”). This unit was known as the “Dread of Morocco.” As he left his family, Simo told them, “This is our land, and we have to defend it.”

Click here to watch the video “Simo Häyhä: The White Death Sniper”.

The Mannerheim Line

Remember the French Maginot Line? It was the defensive fortification built to keep the Germans from invading France. It didn’t work out very well for the French. As part of its defenses, Finland had a similar fortification line, but it was to keep out the Russians. The line of defense was built across the Karelian Isthmus in two phases: 1920−1924 and 1932−1939. As the world situation with Hitler deteriorated, building activity increased in the summer of 1939 but the line was never fully completed. The Mannerheim Line, named after the army’s commander-in-chief, Field Marshal Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (1867−1951), was to protect the south-eastern border of Finland against a Soviet invasion. The heaviest fortifications were built in the Summa area, a section thought to be highly vulnerable to an attack.

The defenses consisted of gun and heavy artillery positions as well as concrete bunkers. The Communist Party was very active in Finland before the war. Its intelligence provided Moscow with details of the Mannerheim Line including photos, road maps with terrain information, and positions of Finnish defensive armaments.

While the Finns were able to repel and delay the Soviet attack in the first months of the Winter War, the Mannerheim Line did not ultimately hold out the Soviet army. In reality, the defensive line was primarily a series of trenches, and the bunkers were very small and spread out. The artillery was not effective either. By February 1940, the Soviets broke through near Summa after heavily bombing the line.

The Winter War

About a week after Hitler and Stalin concluded the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact on 23 August 1939, Germany invaded Poland and several days later, Britain and France declared war. (Stalin invaded Poland on 17 September.) As part of Hitler and Stalin’s “Secret Protocol,” spheres of influence for Europe were determined, and it was agreed that Finland was to be considered within the Soviet sphere.

After Finland’s government refused the Soviet demand for border territories to be ceded, the Soviet army invaded Finland on 30 November 1939. (The Soviet Union was kicked out of the League of Nations as the attack was deemed illegal.) The invaders were initially met with substantial resistance and for two months were repelled by Finnish soldiers. The primary battles took place on the Karelian Isthmus, on Kollaa in Ladoga Karelia, and Kainuu. The Finns were outnumbered by Soviet troops (180,000 vs. 450,000), military artillery pieces (30 vs. 6,541), and aircraft (130 vs. 3,800).

Changing tactics, the Soviets finally broke through Finnish defense lines. After three and a half months, the Soviet positions were strong enough to induce Finland’s government to propose an armistice on 6 March 1940. Stalin knew that Finland did not have enough ammunition, its troops were taking on heavy casualties, and the combined forces of Britain and France could not reinforce the Finns since Norway and Sweden refused to give the Allies the right of passage. As we say in America, Stalin was in “the catbird seat.”

On 12 March, Finland signed the Moscow Peace Treaty. Stalin got exactly what he wanted: more land. The cost to Finland was territorial concession with the Soviets receiving a part of Karelia, the entire Karelian Isthmus, and land north of Lake Ladoga. The Finns lost about nine percent of their country that included most of their industrialized territory, the city of Viipuri (second most populated in Finland), and much of the territory held by the Finnish military. It was a devastating blow to Finland as they lost about thirteen percent of its economic assets, twelve percent of the country’s population, and close to 500,000 Karelians were displaced and lost their homes.

The 15-month period between signing the peace treaty and Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union (i.e., “Operation Barbarossa”), was referred to as the “Continuation War.” After Operation Barbarossa began on 22 June 1941, Germany developed an even greater interest in Finland. Finland on the other hand, was looking for ways to regain control of its lost territories. Finnish troops participated alongside the Germans in the Siege of Leningrad and other battles against the Soviets. The enemy of my enemy is my friend?

After the Winter War, Finland returned almost six thousand Soviet prisoners of war while Stalin sent back about 800 Finnish prisoners. (Twenty percent of the 1,100 Finnish POWs died in Soviet captivity.) The Soviets sustained substantial losses both in terms of men and equipment during the Winter War. The first two months of the war laid bare the weaknesses of the Soviet army. (During the 1930s, Stalin purged most of the military hierarchy resulting in disorganization.) It convinced Hitler that conquering the Soviet Union would be effortless and laid the groundwork for Operation Barbarossa. Finland’s Winter War also exposed the inabilities (and weakness) of the Anglo-French Supreme War Council to deal with the Finnish situation, ultimately resulting to the fall of France.

The Dread of Morocco

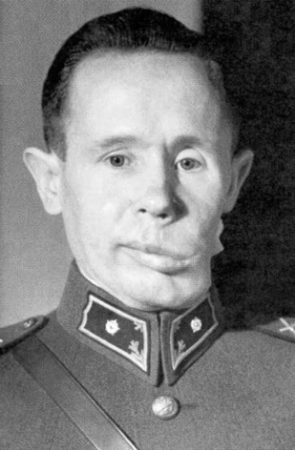

Aarne Juutilainen (1904−1976) was a Finnish officer who served in the French Foreign Legion (FFL) between 1930 and 1935. His tour of duty was in Morocco where he earned the nickname “The Terror of Morocco.” Returning to Finland, Lt. Juutilainen served in the Finnish army as commander of Simo Häyhä’s unit, 6/JR 34.

Juutilainen trained his men hard with guerilla warfare tactics that he learned in the FFL and the unit became known as “The Dread of Morocco.” He was a harsh leader, but his men performed exceptionally well in combat. Juutilainen and the 6/JR 34 were ordered to defend Kollaa during the Winter War. His highly decorated men were described as “good shots and good skiers.” Juutilainen was considered a “relentless fighting” soldier and he became a national hero for his role in the Battle of Kollaa.

The Battle of of Kollaa

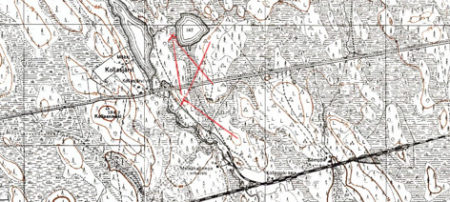

Simo Häyhä served on the Kollaa front during the Winter War. Kollaa was a strategic point for the Soviets as they considered it a breakthrough path to strike behind the Mannerheim Line. In the beginning, Finns put up 4,000 men in defense against 15,000 Soviet troops and hundreds of tanks. Eventually, Finnish soldiers in Kollaa totaled about fifteen thousand while the Soviets invaded with tens of thousands of men.

The Finns pursued a self-inflicted scorched earth policy to deny the Soviet soldiers a place to live other than trenches they dug in the snow. The strategy worked by eliminating warmth and food sources for the invading army but in the end, it was not enough.

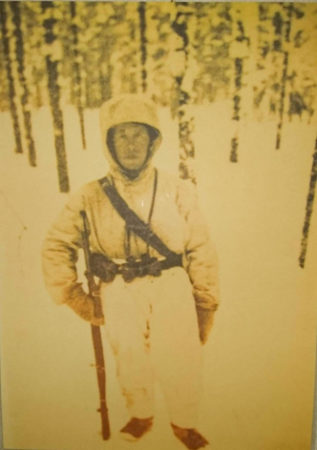

Around Christmas 1939, Häyhä and several other soldiers were featured in the Finnish magazine, Suomen Juvalehti. It is likely that the many images of Häyhä we have today are a result of the magazine article. Häyhä by that time had racked up 150 kills and wrote in his diary, “. . . we shaved our beards and transformed from almost of a moor to more ordinary-looking.” Operating in temperatures between -4o F and -40o F, Häyhä was dressed in all-white camouflage uniforms with multiple layers of clothing to keep him warm. He carried his food in his uniform pockets.

Simo Häyhä and the other White Guard snipers used a Finnish-made rifle, a SAKO M/28-30, based on the Russian Mosin-Nagant, five-shot, bolt-action rifle. The maximum range was about 450 meters, or 123 yards. When Häyhä was part of a group, he used a submachine gun. He preferred an old-fashion iron sight over a modern telescopic sight for three reasons: the telescopic sight would fog up in cold weather, he didn’t have to raise his head as high, and light might reflect off the telescopic sight and reveal his position. Häyhä employed certain tactics to disguise his position. He was only 5’3” and could fit into smaller concealed places. Häyhä would lie down in snow pits before the sun came up and not exit until after dark. He would put snow in his mouth to prevent his breath giving away his position before pulling the trigger. Padding underneath the rifle eliminated the “puff” of snow after firing. Waiting for his prey, Häyhä was virtually invisible and Soviet counter-snipers sent out to eliminate him were quickly picked off.

The Injury

On 6 March 1940, Häyhä was shot in the left jaw by a Soviet soldier using an exploding bullet. He appeared dead and was left in a pile with other bodies. However, someone noticed his leg twitching and they found him alive albeit unconscious. Häyhä lost his upper jaw, most of the lower jaw, and most of his left cheek.

Simo Häyhä regained consciousness about the time the peace treaty was signed. He endured a 14-month recovery and twenty-six surgeries. (The doctors used part of his hip bone to reconstruct the jaw.) Häyhä’s obituary had been written and published. He wrote home, “Stop the funeral, the deceased is missing.” Despite his wish to continuing serving in the army, Häyhä’s days as a soldier were over. He made a full recovery but was permanently disfigured.

Russian Kills

According to Häyhä, he killed about 500 enemy soldiers. While this number is generally accepted, not all “kills” were confirmed by a witness and at least half were accomplished using a submachine gun. In recognition of his contributions, Häyhä was awarded a rifle of honor in February 1940 and proclaimed “a hero of Finland” by the Finnish government. He was awarded the Cross of Kollaa Battle, First- and Second-class Medals of Liberty, and two classes of the Crosses of Liberty.

Simo Häyhä’s Last Years

A modest, mild-mannered, and somewhat reclusive man, Simo never married. He continued hunting and breeding dogs. Häyhä conducted hunting parties that attracted well-known people. He passed away in a veteran soldier’s retirement home on 1 April 2002 and is buried in Rautjärvi. The inscription on Simo’s gravestone is Koti-Uskonto-Isänmaa, or “Home-Religion-Motherland.”

The fight between the Finnish army and the Soviet Red army was like a David and Goliath battle. At the time, the Soviets had the largest military in the world and Simo Häyhä became a symbol of one man fighting overwhelming odds with just a rifle. He became a legend in his country despite his humility and his legend has only grown with time.

There is a museum dedicated to Simo Häyhä. It is the Kollaa and Simo Häyhä Museum located in Rautjärvi near Simo’s birthplace (i.e., his parent’s farm).

Click here to visit the museum web-site.

Stew’s Final Words

After writing several blogs on World War II snipers, I guess every sniper, regardless of nationality, gender, or age, shares the same last name: “Death.”

Simo was once asked if he had any remorse and he answered, “I did what I was told to do, as well as I could. There would be no Finland unless everyone else had done the same.”

And lastly about the Winter War more than eighty-years ago:

- Russia invaded a neighboring country for the purpose of annexing territory.

- The outnumbered country rose up to fight the invaders.

- It was evident the “superior” Russian army was highly overrated.

- The Russian generals and military leaders were inept.

- Hundreds of Finns were displaced and lost their homes.

Sound familiar? History does repeat itself.

Next Blog: “The Tartan Pimpernel”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

BBC. The world’s deadliest sniper: Simo Häyhä. HistoryExtra, February 2017. Click here to read the article.

Burgess, Robert F. SIMO HÄYHÄ: The Man from Rautajärvi aka The White Death. Chicago: Spyglass Publications, 2015.

Chew, Allen F. The White Death: The Epic of the Soviet-Finnish Winter War. KiwE Publishing Ltd., 2008.

Edsel, Robert M. with Bret Witter. The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History. New York: Center Street, 2009.

Gilbert, Adrian and various. The Sniper Anthology: Snipers of the Second World War. Yorkshire: Frontline Books, 2012.

Häyhä, Simo. The Diary of Simo Häyhä. White Death Diary. Click here.

(Note: this appears to be a blog that has incorporated parts of Häyhä’s diary or memoirs).

Kinnunen, Annika. Sotamuistoja – Simo Häyhän kuvaus talvisodasta. Bachelor’s Thesis, 2019. Click here.

(Note: this document is in Finnish and the author has reportedly used parts of Häyhä’s diary or memoirs).

Larsen, Andrea. Translated by Sheila Muir. SIMO HÄYHÄ, The White Death: The incredible true story of the deadliest sniper ever. Independently published, 2022.

Saarelainen, Tapio. The White Sniper: Simo Häyhä. Oxford: Casemate Books, 2016 (reprint edition).

Taracasemate. Meet the Author: Tapio Saarelainen. The Casemate Blog, 9 November 2016. Click here.

Trotter, William R. A Frozen Hell: The Russo-Finnish Winter War of 1939−1940. Chapel Hill: Algonquin books, 1991.

After being wounded in March 1940, Häyhä wrote about his experiences during the Winter War. However, the manuscript was not discovered until 2017, fifteen years after his passing. I was unable to locate a complete copy.

Mr. Saarelainen is a retired veteran of the Finnish army. He spent twenty-years training young snipers and helped write the army manual for snipers. As part of his research for his book, The White Sniper: Simo Häyhä, Mr. Saarelainen interviewed Simo Häyhä dozens of times starting in 1997. Mr. Saarelainen’s book is referenced in many articles and seems to be the definitive history of Simo Häyhä. The article listed above in BBC HistoryExtra includes many interesting images of Häyhä during his post war years. You might want to check it out.

Interview with Simo Häyhä, click here.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

The day you receive this blog, Sandy and I will be traversing the Suez Canal. We’ve been through the Panama Canal, so it made sense for us to float down the Suez Canal. The history of each canal is fascinating and actually share some common facts. However, from an engineering and construction standpoint, they couldn’t be more dissimilar. If you’re interested, I suggest you read David McCullough’s book, The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal 1870−1914. Mr. McCullough is one of my favorite historians and believe it or not, he only wrote nine books.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Do you remember Marianne Golding’s guest blog last year? Click here to read An (extra) Ordinary Holocaust Story of Survival. It is the story about her family’s personal experiences during the Second World War and Holocaust. Well, it turns out the blog was responsible for one of Marianne’s distant cousins contacting her. They share the same great-grandparents (i.e., Baruch Placzeck). It seems her cousin has “long-lost” information that Marianne can use for her book. I have a feeling Marianne won’t stop here and she’ll go down some rabbit holes using this new source of information.

It’s always nice to hear how our efforts benefit our friends and readers. Thanks, Marianne, for letting us know about this wonderful news!

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Shepherd.com is like wandering the aisles of your favorite bookstore.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Check out Stew’s new bookshelf on the French Revolution.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross