I wrote a blog in 2019 about The White Buses (click here to read the blog). It was the story of how Count Folke Bernadotte, a Swedish diplomat, negotiated with Himmler toward the end of World War II for the release of thousands of women imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps. Using buses painted white while adorned with the Red Cross symbol, the destination for the women was to be neutral Sweden and freedom. While many of them were saved from SS death marches as Soviet troops advanced westward, their journey through Germany on the White Buses was no less perilous.

One of our readers, Professor Roger Ritvo contacted me about the blog and filled me in on his research project about the White Buses. At some point in our discussions, I suggested he write a guest blog based on his research. (Co-authors of the article are Caitlyn Traffanstedt and Allison Stone.) Fortunately for us, Roger agreed, and I have had the opportunity to read their two articles, 10 Gifts from the White Bus Rescue of 15,345 Nazi Prisoners in 1945 (Part 1) and Ten Gifts (Part 2).

Our blog today is a collection of selected excerpts of the paper, and we have chosen several of the gifts to share with you. I hope you enjoy this sampling and if you do, I have listed the links to their articles in the recommended reading section below.

For an update on our 2023 goals, please make sure you read the “What’s New with Sandy and Stew” section at the end of this blog.

Introduction

In the winter of 1944-45, rumors of Hitler’s order for a “final solution” were spreading around Europe. A supposedly “neutral” Sweden opened back-channel conversations with Heinrich Himmler about removing Swedish prisoners from the doomed concentration camps. The diplomatic pressure on Sweden to stop selling materials to the Nazi regime despite their professed neutrality also opened conversations of what they would do about their own citizens being interned in the death camps. These negotiations ultimately led to a plan to lead convoys of buses, and trains into Ravensbrück, Neuengamme and other camps in an effort to rescue the Scandinavian citizens inside their gates.

Each of these buses was painted white, with a red cross to indicate to any troops and planes that they were peaceful and to avoid attack. Even when the convoy stopped, they would spread a huge Red Cross flag on the ground to avoid inadvertent bombing. There were many unknowns going into the mission. Nobody really knew how many prisoners would even be there, how they would react, and if the convoy passengers would make it out alive.

Staffed by a pair of drivers, the typical bus was retrofitted to carry about 8 stretchers plus seats for 36 passengers, care-giving staff, and support personnel. The rescue missions were comprised of three units, each with a dozen buses, a dozen trucks plus supply/support vehicles. Each bus only had enough Motyl fuel (a mixture of alcohol and gasoline, usually in equal parts) to cover about 50–60 miles on a full tank. Thus, additional support trucks were mandatory to keep the process in motion.

Arriving at the camps in April of 1945, the convoy of Red Cross buses stood welcoming prisoners as guards simply yelled at them to get “OUT!” One prisoner recounts “we were given a parcel; it was quite heavy . . . as . . . I wasn’t very strong after the scarlet fever. I asked my mother if I could leave it. She said, ‘No, there will be food in there.’ My arms ached but there were delicious things inside. I ate the powdered milk by the spoonful. Some people died because they overate after being hungry for so long.”

The shocked volunteers from the convoys met prisoners in bad shape after their time in the internment camps. Nurse Margaretha Björcke recalled “I have never in my twelve years practice as a nurse seen so much misery as I witnessed. Legs, backs and necks full of wounds of a type that an average Swede would be on sick leave just for one of them. I counted twenty on one prisoner, and he did not complain.”

The bus trips through Germany at the end of a war were full of unknowns and highly dangerous. Questions remained if the roads would even be passable, and the knowledge that if Allied planes didn’t recognize the convoys for what they were, bombing was always possible. One convoy was indeed mistaken for troops and bombed on April 25, 1945, killing and injuring members of the convoy. What awaited these released prisoners at the end of their precarious journey to freedom? Many believed this was another cruel Nazi trick even with the food parcels.

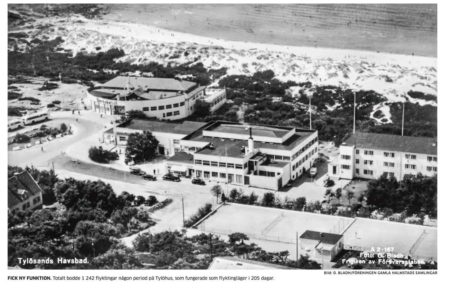

When some buses reached Odense, Denmark, other former prisoners were taken to Copenhagen and then sailed to Sweden for quarantine for tuberculosis and other diseases in the Tylösands and Strängnäes facilities. On their arrival to the destination cities and seeing the Swedish doctors, some of the skeletal survivors screamed, “I don’t want to burn. I don’t want to burn,” imagining SS doctors. Swedish nurses fainted at the sight of the ravaged bodies.

The reentry and screening process included burning the clothes upon arrival for health and sanitation reasons. Several months after arrival, Lund University Professor Zygmunt Łakociński and his colleagues interviewed 514 people to begin the process of documenting the atrocities and crimes against humanity that characterized Nazi rule. They learned that many women had hidden small objects beneath their clothes, or in the heels of their shoes. A scrap of packaging inscribed with a poem recalled from memory, a tiny cross fashioned of metal bolts, a tiny doll made of scraps of fabric, and a miniature hand-written calendar were saved for history.

One of the quarantine facilities was located about 75 miles from Malmö in Halmstad at the old “Spa Tylöhus,” now part of the Hotell Tylösands. When the war finally ended shortly after these survivors were freed, they held a “peacefest” in their new accommodations. What a celebration it must have been. The episode at the Hotell Tylösands may therefore, despite all, be one bright spot in hard and dark times.

Ultimately the greatest gift of the White Buses’ mission was the gift of life. Life for every one of the individuals who were rescued from the concentration camps. A chance at living and thereby giving back through those lives. As we highlight 10 of those lives and the impact they have had on the world, we invite you, the reader, to reflect on the countless other lives that have been changed due to the courage of those participating in the White Bus rescue.

Gift #1: Anita Kemplar Lobel

“My life has been good. I want more. Mine is only another story.”

−Anita Kempler Lobel

Young Anita lived in Kraków, Poland with her parents and younger brother. When the war came in 1940 and her parents were forced to disappear to avoid capture, Anita and her brother Bernhard (Gift #2) were taken by their nanny (whom they called Niania) into the Polish countryside to be kept safe. “Aside from the fact that there was an outside force that hated us and chased us, I always felt my brother and I were protected by this person who chose to protect us. I loved her and she loved us, and I think that this was very important.”

Young Anita was one of the many rescued from Ravensbrück by the Swedish Red Cross convoys of White Buses and taken to Sweden. With little knowledge of what was happening, Anita and her brother traveled on a bus under the Red Cross symbol to a ferry which landed in Malmö, Sweden, to begin their journey back to life, freedom, and contribution.

Among the many stricken with tuberculosis, Anita and her brother joined other children in a sanatorium upon arrival. She recalls the ‘restorative’ experiences there. Having some friends, learning a new language, reading books, being cared for by “stoic, . . . calm”, and “reasonable” people in an “orderly” society. Anita recalls that “between the ages of 5 and 11, I knew no libraries, no schools, no books. I did not know how to read. I lived in a wicked country during a wicked time. I was hunted and often hungry.”

After the White Bus ride to freedom, she “was recovering from madness and no civilization and tuberculosis, in a sanatorium in the south of Sweden. I discovered books. They were handed to me by kind nurses who gave me food and clean clothes. Who tucked me into a clean bed. Who smelled clean and nice.”

Two years after the war ended, Anita and Bernhard reunited with their parents, and after 7 years in Sweden, the Kempler family moved to New York City. Anita graduated from Washington Irving High School and enrolled at the Pratt Institute of Fine Arts. While in a school play, she met the play’s director Arnold Lobel. They married in 1955, lived in Brooklyn, had two children, Adrianne and Adam. Together, Arnold and Anita wrote and illustrated over 100 children’s books that still enthrall youngsters now three generations later. The Frog and the Toad are often some of the first words kids learn. The numerous awards and honors they received are richly deserved.

Sadly, this love story has an ironic ending. Family man, collaborator in writing and illustrating, Arnold was gay at a time when it was brutally stigmatized. People with AIDS were pariahs in many parts of the U.S. (and world) society. Famous AIDS activist Larry Kramer decried the official inaction to help people with AIDS and to develop medications to fight the disease; his autobiography is entitled Reports from the Holocaust. Arnold shared his secret with family in the early 1970s; he and Anita divorced about a decade later. When Arnold died in 1987 from the complications of AIDS, he joined a list which the Associated Press entitled “It has a name: AIDS.”

Anita Lobel (b. 1934) survived one Holocaust, lost her former husband to another, and still had the courage to live a full life. In 2021, her “second husband, the great love and true romance of my life for the past 34 years, died.” Her life combines the gift of love with the reality of loss, the gift of Anita’s life view could be one of horror, darkness, death, and hatred. Rather, a survivor, an author, illustrator, singer, actor and teacher, her work remains animated, hopeful, and helpful. Her ‘children’s’ books contain clear lessons and profound truths about life for adults.

Reflecting on her childhood experiences which saved her life by feigning to be a Catholic, once Anita became settled in New York City, she realized “Oh well, I am not going to lie any more. I am not going to pretend.” A woman coming to terms with her life, its opportunities, and her skill to make others’ lives richer.

What a gift!

Gift #2: Bernard Kempler

Born in 1936 in Kraków, Poland, Bernhard was only three years old when the Nazi forces invaded Poland and forced his father into hiding and his mother to flee. Bernhard and his older sister, Anita (Gift #1), were left to the care of their governess (whom they called Niania) who took them into the countryside hoping to hide them from the Nazi’s. Over time Niania no longer felt it safe and secreted them to a convent for protection. They were discovered hiding in the convent, forcefully removed, and taken to Ravensbrück. Bernhard being a young boy should not have been put into the women’s and girls’ concentration camp, but in an effort to keep him with his sister, he was dressed as a little girl and miraculously remained undiscovered until their rescue by the Swedish White Buses in 1945.

He recalls his experience in the camp saying “I had no idea what was going to happen. I . . . wanted to survive from day to day . . . I didn’t know why I was in (the concentration camps) in the first place.” Among other limited memories of his time in the camp, he shared that as the war was coming to an end “We were getting American care packages. We had food; it was lying in mounds inside the camp. That was a sign that something good was happening. Of course, I didn’t know what America was, or who these people were, or why this was happening.”

Bernhard’s recollection of the White Buses rescue is also limited. “Almost immediately we got packed into these buses and taken out of the camp. I know now and knew shortly thereafter, that it was the Swedish Red Cross, and we were being taken to Sweden. But I didn’t know what Sweden was. Some of these buses on their way up through Germany, and through Denmark were bombed. The people who were too sick were placed in the luggage compartment. They became like hospital beds. But then everyone had to get out of the bus and go on the side of the road because we were being bombed. I don’t know who was bombing us.”

Bernhard’s first years after rescue on a White Bus convoy were sickly, recovering from tuberculosis, learning Swedish since he had forgotten Polish, “learning how to live just as a child, under normal circumstances, how to play games, how to talk, how to be in class, how to . . . everything was just totally new. Nothing was to be taken for granted” and eventually reuniting with his parents in 1947. They remained in Sweden for 7 years, without a home, stateless. “My father had some very distant cousins [in America]. He felt there would be better opportunities for him to get started again in some kind of business. I think the main motivation was to get out of Europe. First, we spent a week on Ellis Island . . . right before Christmas, 1951 . . . Finally, they checked our papers, and found everything in order.”

“We were adaptable . . . we just learned to be adaptable. We wanted to be adaptable. It was difficult, but I didn’t go around, and think, ‘This is very difficult’ . . . I just did it.”

Losing much of his contact with his family upon leaving for college, Bernard did not think about or talk about the war much. Despite his parents socializing and maintaining contact with other refugees, Bernard focused on adapting. Eventually he began to wonder if all these events had really happened to him or not. He tells the story of his return to Kraków and Auschwitz where everything was real again, and he knew that he had not made up any of the horrors that he faced as a young boy.

While in Poland he also ran into one of the nuns who had been in the convent where he was hidden many years earlier. She was astonished that he had survived. This trip was important because “One of the main values of going back to these places was to take that part of your past from this never, never land of dream, fantasy, nightmare . . . because it feels that way.”

“I went around Kraków. I saw buildings that my Uncle Sigmund had built. I went to the apartment where we had lived, and I remembered. I saw that balcony where I had played as a child of two or three. I went to the park where we had met and seen my mother from a distance. It was not an unpleasant experience. It was a very reality-affirming experience. But it’s not easy to talk about as one story. When I was at the children’s conference, that was a big thing, everybody wanted you to tell your story. It’s difficult to do that, not because you get overwhelmed by your feelings . . . everyone thinks that that’s the problem . . . but you end up talking about it like a story. So, it’s a problem. You don’t quite know how to have it, how to be with that past. Including why did I survive when so many others didn’t?”

The Shadow Side of Self-Disclosure represents the intersection of Bernhard’s professional career as a psychologist with his childhood experiences as a Holocaust survivor. He asserts that “responsible” self-disclosure of reactions to events, feelings, and other life events is part of being a mature adult, whereas premature disclosure can be harmful in the short and longer term. An academic scholar and psychologist, Bernhard practiced in Atlanta for decades and served on the faculty of Georgia State University. He helped people through difficult struggles so they could better cope with life’s stresses. He married the former Diane Gail Solomon; their son was born in 1964.

Yad Vashem serves as Israel’s national official memorial to preserve the memories of those who died in the Holocaust, to honor those who helped end the carnage, and hopefully prevent such atrocities from happening again. Bernhard Kempler has a special connection to this memorial which plants trees as a symbol of life, of endurance and recognition. “When I found out about Yad Vashem, [ I ] decided that it was very proper for me to honor [our governess] Niania (whose real name is Rozalia Natkaniec). Niania had died right after the war, but then later, I found out that Ruja (note: another Jewish child saved by Niania) was alive and living in the same apartment where we had been hiding for a while. So, I wrote up their stories, and my story, and what had been done; I sent it to Yad Vashem. Niania/Rozalia was accepted as a Righteous Gentile.”

To assert life. To cause life to recognize (one’s authority or a right) by confident behavior. To take a proactive approach despite the circumstances that are inflicted upon oneself. This was Bernard Kempler.

Bernhard’s is a life well lived with the gift of service to others.

Gift #3: Nelly Langholm

Ships and marine life provide bookends to important chapters in Nelly Langholm’s life (1924−2020), surrounding years of horror. Arrested in Norway in 1942, she was a prisoner on board the ship Monte Rosa enroute to Ravensbrück.

She remained silent for “almost 50 years before I talked to anyone about the experiences.” Yet, the atrocities she witnessed and endured are clear. A teenager with a crush on someone who “said his name was Wolfgang Grimm and he had come to see me. I didn’t know why, and he wouldn’t say. But he talked to me, and he was so lovely and sweet and played the piano. And he came back the next day. And the next day. And I fell in love with him.” After her uncle was killed by a German explosive and losing a cousin to the Nazi police, Nellie did what young adults do: she wrote a “Dear Wolfgang” letter, ending the infatuation. “The next day the Gestapo came to my house and arrested me. They told me they had read the letter in which I said I was an enemy of Germany.”

Imprisoned for nine months in two Norwegian transit camps, she arrived in Ravensbrück on June 2, 1943.

Being so young, she probably did not understand the larger picture of a world-at-war. Being arrested “felt right in a way; I had done this terrible thing by falling in love with a German and the Germans had killed our family. I thought I should be punished.” Images from this undeserved ‘punishment’ include:

- Witness: German shepherd guard dogs mauling a 15-year-old Yugoslavian girl to death.

- Memory: When lucky enough to have underwear, it was verboten (forbidden) to wash it.

- Witness: Starvation rations resulting in massive weight loss.

- Memory: “I was so greedy that I ate a large piece of pork without sharing it. I became very ill afterwards” because her system was shutting down.

- Witness: The relative excitement when an all-too-meager Red Cross package managed to get through to prisoners, minus whatever the Nazi guards secreted away.

- Witness: “Christmas and New Year’s days in 1943. On Christmas Eve, we were sent out of the barracks in the evening and dressed stark naked for de-lice. We stood for many hours while the snow came down. To keep warm, we stood close together.”

- Memory: Norwegian prisoners would disappear in the “Night and Fog.” (Stew’s note: click here to read our blog, Night and Fog)

- Witness: Prisoners about to be executed were so thirsty that they threw themselves into little puddles to try to drink the murky moisture.

- Memory: “Crying with homesickness.”

- Memory: Sewing and hard physical labor in horrific conditions.

- Memory: Suffering from tuberculosis, Nelly was saved by the White Buses on April 9, 1945.

After the war, she reconnected with, and married, a Norwegian journalist who had also been a prisoner; they had three children. Nelly never forgot the Red Cross parcels while a prisoner in Ravensbrück and those heroes of the Swedish Red Cross and the White Buses. “This made me make an important choice; I was to spend part of my life working for the Red Cross.”

And she did. After training at a Red Cross nursing school, she staffed an emergency room in Oslo; in 1971 she became a psychiatric nurse. Several years later, Nelly landed “the dream job as a cruise nurse on the MS Sagafjord, on what was then the world’s finest cruise ship.” Later, in her mid-50s, she became a nurse in the North Sea working on oil rigs and supply ships. She was also honored to christen an oil company support vessel for Mobil Oil in June 1985 in honor of her service on the Statfjord A oil platform.

Once imprisoned and transported by ship into Hell, Nelly Langholm’s life voyage included service on land and on the sea helping others.

Gift #9: Erik Viggio Ringman

How does one say ‘Thank You’ to those who risk death to save strangers in need? Does history even remember these 308 bus drivers, medical personnel (perhaps as few as 20) and support staff whose collective actions can be called heroic? They are another gift of the White Bus mission, an example of service before self.

The first team included 15 ambulances under the command of the Chief of Transportation Karl Gottfrid Björck (1893−1981). These buses and support vehicles rescued 786 female prisoners from Ravensbrück, the first of what would exceed 15,000 lives, people, souls, parents, children, brothers, sisters . . . survivors. On April 24th, Lt. Gösta Hallqvist’s mission departed with 706 women, hopefully on their way to safety in Denmark.

Sadly,

- possibly because of the fog of war.

- perhaps because the British wanted to close off Nazi escape routes.

- perhaps because there were Nazis on the buses as guards and escorts.

- perhaps because Nazis were using the Red Cross convoys to escape.

- perhaps because . . . well, who knows?

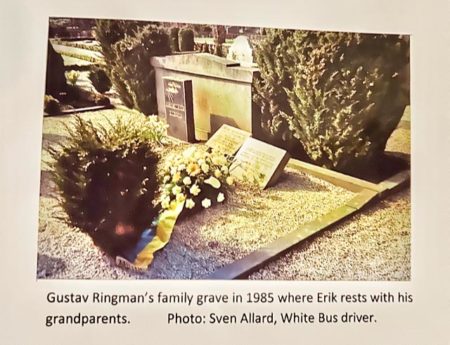

The next day Hallqvist’s column was attacked, killing many including volunteer driver Erik Viggo Ringman; Lt. Hallqvist survived a near-fatal head injury.

Was this driver just another casualty of war? Perhaps, but he is also a reminder of heroism in action. A private in the 3rd platoon, (Military ID 359-1-38), Erik Ringman (1918−1945) drove a Volvo Spetsnos, a light truck converted for this journey. The convoy leader, Lt. Gösta Hallqvist referred to Ringman as his “best driver.”

In the annals of the Second World War, April 25, 1945, is often remembered for three important events. At a global level, it is the day that 46 nations met to start the creation of the United Nations. It was also when American and Soviet forces met at the river Elbe to form a united front against the Nazis. And, most relevant to this history, it was the day that approximately 359 British Royal Air Force bombers accompanied by 98 Mustang escorts from the U.S. 8th Army Air Force bombed (not as successfully as planned) Hitler’s holiday retreat known as Berchtesgaden. It is also the day that other British planes were flying over the safe skies of Germany looking for military targets. Somehow, their flight paths intersected with the escape roads of the White Bus convoy.

Erik Ringman’s last trip was on April 25 when these Allied planes bombed his convoy. As part of the bombing of Wismar (a large city in northern Germany), travel on the Wismar Road was extremely dangerous. Another group of vehicles was also attacked, killing and injuring dozens. Despite being painted white with red crosses as identifiers, the buses came under attack, killing as many as 45 additional former prisoners and their rescuers. When Åke Svensson returned to Ravensbrück to load the last of 934 prisoners into 20 buses, he saw two Red Cross vehicles in the ditch, shot to pieces. One of these was driven by 27-year-old Private Erik Ringman. His coffin was transported home, fittingly perhaps, that the Volvo Private Ringman drove became a hearse loaded onto other vehicles for the journey home for his remains. At his funeral, a colleague spoke for many about Ringman’s legacy and gift: “This [is a] true Scandinavian ceremony, when the Swedish soldier was buried by a Norwegian officiant in a Danish church.”

What has yet to be mentioned is the legacy Erik Ringman left with his family and his country. Marie Magnusson, a third-generation descendant of Erik’s cousin, is striving to keep his legacy alive. Marie simply wants Erik to “be known” as well as “the others” that were on the White Buses. Marie mentions Erik as a “caring soul,” someone who was not driving White Buses and trucks for attention or limelight, but someone who simply wanted to make a difference as opposed to being a bystander. While war is characterized by death, persecution and atrocities, this moment of Erik’s heroism shines light on human empathy and pure sacrifice.

This is how the country mourned Erik; but death is personal and remains in memories of those who knew and loved the deceased. In many families, the stories handed down from one generation to the next become legends, perhaps enhancing events, and filling in gaps. Marie Magnusson remembers how the family regarded Erik, his work, his life and sadly his death as the country also mourned at the time. To them, he was “a hard-working man, honest, cared for other people and a good friend. He had a fiancé, but never married. My grandfather was the one who was initially supposed to go with the Red Cross and (I guess they talked to each other) Erik told my grandfather that it was better if he (Erik) went instead since he did not have any children and my grandfather had two at the time.”

Service above self is a legacy that both a country and a family hold dear. What a gift!

Stew’s Comments

These are just four of the ten “Gifts” that Roger, Allison, and Caitlyn have written about in their articles. It is a tribute to the people surrounding the April-May 1945 White Bus rescue efforts, either as a survivor or rescuer, and the “gift” each person developed or left behind as their legacy because of their experiences.

You are invited to read the entire articles including the other “gifts” using the following links:

Part 1: Click here.

Part 2: Click here.

__________________________________________________________________________

An Interview With Professor Roger Ritvo, Caitlyn Traffanstedt, and Allison Stone

How did you become interested in this history that is not well-known outside of Scandinavia?

Roger: It started in the movies with two documentary films: Every Face Has a Name and Harbour of Hope. After watching these, I wondered how can I find out more about this remarkable story. When my university, Auburn University Montgomery, had funds available for a faculty member to work with a graduate student on a research project, I applied, and we received partial support for this dive into history.

Caitlyn: To be honest, Professor Roger Ritvo. He gets all the credit for this, and I want him to. He called and offered me an opportunity to work on this little-known subject. I did not have a clue what I was getting into, nor did I feel “qualified” to do so. What a journey it has been – this was a subject I knew nothing about outside of the Holocaust, but it’s so important that people know about this and keep it in their back pocket to understand history, learn from it, grow from it and be advocates for it for generations to come.

Allison: I have always been intrigued with World War 2 and the experiences of those who were in the concentration camps. It is marvelous to me to learn of the goodness that was expressed by so many in those difficult times and thereafter. Learning about the White Buses rescue shows humanitarian actions make a difference; it was another circumstance where unexpected people stepped in and were just plain good in a situation where things were abysmal. I am inspired by hearing about people treating others as people and showing brotherly love despite religious, cultural, or any other differences. This is a prime example of the difference that a few people can make in the world.

Why is this history relevant today?

Roger: Why not now? If not now, when? My professional scholarship includes a book entitled Sisters in Sorrow which presents the biographies of a dozen women who served as nurses, aides, and assistants in the hospitals and infirmaries in the Nazi concentration and death camps. Caitlyn and Allison had much less knowledge of the Holocaust and delved into this history with enthusiasm and passion. As the article notes as its last words: “Lest we forget.”

Caitlyn: Although I don’t have a background in history, I think it can be forgotten or even repeated (negatively or positively) if we don’t know and appreciate how we’ve accomplished, endured, and survived very difficult, but sometimes very rewarding times. I’ve always been intrigued and curious about learning more about the Holocaust and the events leading up to and after the brutal period. The White Buses history provided the opportunity to delve into a remarkable chapter of this period. I could not be more thankful for this opportunity to be aware of the past.

How did you make the stories come to life?

Caitlyn: By physically meeting, seeing, and interacting with the stories and recollections in-person. It’s one thing to read an article; it’s another to meet someone in-person who was related to a survivor or individual actually involved in the rescue. It also brings everything to fruition when you meet other people who are also very interested in the research. These connections could last a lifetime.

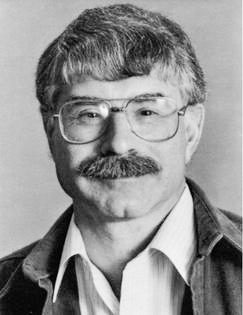

Roger: Lots of time sitting at my desk, sending emails, scheduling Zoom conferences, watching videos from the US Holocaust Memorial and Museum, accessing the resources of the Fortunoff Collection at Yale, reading the extensive transcripts of over 500 interviews conducted in Sweden within months of the arrival (now housed at Lund University) and the University of Southern California Shoah resources prepared us to make the most of our trip in late August – mid September 2022 to Sweden and Germany. We even arranged to meet in Lund, Sweden with two 2nd generation cousins of Erik Ringman, the Red Cross driver who was killed by British planes while driving prisoners to freedom in Denmark/Sweden.

What are several lessons learned from this work?

Roger: I co-authored a book in the late 1990’s entitled Sisters in Sorrow which recorded the work of amazing women who served as health providers while prisoners in the Nazi concentration and death camps. One important lesson for today is to try to avoid making judgments about what people did in these unimaginable circumstances to stay alive. While I am not a religious scholar, I do believe in the biblical commandment to “choose life” (Deuteronomy 30:19). Survival was in itself a form of resistance to the Nazi machine. A second lesson is the power of a dream. Count Folke Bernadotte of the Swedish Red Cross saw an opening to rescue thousands of Scandinavians, found a path to Himmler and negotiated the release of what turned out to be over 30,000 prisoners during the chaos of the closing weeks of World War 2. Yes, there are some who raise concerns about his means and methods, but the result is that tens of thousands were given the opportunity to live.

Caitlyn: I think many lessons can be taken from this research and subject in general. This is a reminder that darkness is real; we can either choose to live in the darkness or choose to live in the light. The Holocaust and this research on the White Buses Rescue are a direct result of living and walking in darkness. Narcissism, egotistical maniacs, and pure evil are all components of this. Thus, this is a reminder to us all – are we going to choose to live and walk in darkness or the light? One other lesson is making the best decision one has at the time with the information and circumstances they have at the time. Could more have been saved? Could people have been saved sooner? Maybe. One can speculate for hours. We are human. We can compare and think about how we would have done things but point blank: You do not know what you would do until you are in a situation where you have to make very difficult, but quick decisions. It can change your perspective.

Allison: Every life has value. Even though we point out that thousands were saved in the rescue, the “10 Gifts” articles highlight that every individual life was a gift as well. To do good, people do not need to save thousands. Recognizing the impact that one person’s life can have allows us to recognize that even what appear to be small drops in the pond have lasting impact on so many people. I hope to always remember that each person’s life is invaluable.

Biographies of Roger Ritvo, Caitlyn Traffanstedt, and Allison Stone

Professor Roger Ritvo is the Distinguished Research Professor of Management Emeritus at Auburn University Montgomery (AL) and was presented with the Teaching Excellence Award in the College of Business for the 2013-14 academic year. He also serves as a Lecturer in the Health Administration programs at the University of Colorado Denver’s Business School. Roger served as Senior Policy Advisor to two secretaries of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

Roger Ritvo is the co-author of Sisters in Sorrow, a study of a dozen women who served as nurses, aides, and health providers while prisoners of the Nazis. The paper on the White Buses is an extension and augmentation of Sisters in Sorrow. Roger is a prolific author having published nine books and numerous articles co-written with colleagues and students. A fun fact about Professor Ritvo: along with his daughter, he opens and closes the rink door to allow skaters to go on the ice at the United States Figure Skating Association national championships.

Allison Stone is an MBA candidate at the University of Colorado Denver. She works as a senior clinical researcher specializing in complex drug and neurology studies and is passionate about healthcare and leadership. As a longtime student of WWII history, this project has inspired and deepened her appreciation for the incredible people whose humanitarian values and actions still have meaning today.

Caitlyn Traffanstedt serves as a performance improvement analyst within the Office of Patient Safety at East Alabama Health in Opelika, AL. She is a graduate of Auburn University and currently working on her Master of Health Administration at Auburn University at Montgomery. Caitlyn also serves as secretary and co-director of the East Alabama Region for the American College of Healthcare Executives of Alabama. In her spare time, Caitlyn enjoys working with her husband, Cody, on restoring their 100-year-old house.

Next Blog: “Cynthia: The World War II Mata Hari ”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Learn More About the White Bus Rescues and The Gifts ★

Gertten, Magnus (Director). Every Face Has a Name. Menemsha Films, 2015. Swedish with English subtitles. Non-USA Format, PAL, Reg. 2 (Europe) Import-Sweden.

Greayer, Agneta and Sonja Sjöstrand. Translation by Annika and Peter Hodgson. The White Buses: The Swedish Red Cross rescue action in Germany during the Second World War. Stockholm: The Swedish Red Cross, 2000.

Helm, Sarah. Ravensbrück: Life and Death in Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women. New York: Anchor Books, 2015.

Hore, Peter. Lindell’s List: Saving British and American Women at Ravensbrück. Stroud U.K.: The History Press, 2016.

Kempler, Bernard. The Shadow Side of Self-Disclosure. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. Volume 2, Issue 1, Winter 1987.

Lobel, Arnold. Frog and Toad Are Friends. New York: HarperCollins, 1970.

Ritvo, Roger A. and Caitlyn Traffanstedt and Allison Stone. 10 Gifts From the White Bus Rescue of 15,345 Nazi Prisoners in 1945.

Part 1: Click here.

Part 2: Click here.

Ritvo, Roger A. and Diane M. Plotkin. Sisters in Sorrow: Voices of Care in the Holocaust. College Station (TX): Texas A&M University Press, 1998.

Ström, Lennart and Magnus Gertten (Producers). Harbour of Hope. Auto Images, 2011. Swedish with English subtitles. Non-USA Format, Reg. 2 (Europe) Import-Sweden.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are settling into the new year (as I hope all of you are) and trying to come up with a “game plan” for 2023. High on our list is to get the second edition of volume 2 of Where Did They Put the Guillotine? Marie Antoinette’s Last Ride published. We are close to sending the final file to our printer, Pollock Printing, in Nashville.

As always, we continue to write and publish our bi-weekly blogs. Since we’re in the middle of the three-volume set on the occupation of Paris, we’ll continue the theme of World War II for the blogs. The third leg of our 2023 goals is to get volume two (book no 6 of our walking tour series) of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? Roundups and Executions published and available for purchase.

One of our trips this year is a river cruise on the Elbe River. We will end up in Berlin for three days. The eighth book in our series will be Where Did They Put the Führerbunker? A Walking Tour of Nazi Berlin (1933−1945). Neither Sandy nor I have been to Berlin. So, we will use our limited time there to acquaint ourselves with the city and in particular, the methods of public transportation. I have begun an outline of some of the potential stops in the future book and hopefully, we’ll have time to visit these sites.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

It goes without saying that we are very appreciative to Roger, Allison, and Caitlyn for their blog today. I know for several of them, this project introduced them to many facts about World War II and the Nazis that seem to have gotten lost in the haze we call “History.” There are many lessons to be learned from the 1930s and 1940s that unfortunately are not covered any longer in our schools. One thing I’m sure Allison and Caitlyn walked away from the project with was a new appreciation for the mantra, “Never Forget.”

I’d like to thank Alisa L. for her kind comments on our blog, British Mandate. (Click here to read the blog).

Martin P. contacted us regarding the blog, Last Train Out of Paris (click here to read the blog). Martin’s father was one of the 168 downed Allied airmen captured in 1944 and sent to KZ Buchenwald to be executed. Martin did not think his father knew Stan Booker (click here to read the blog, Stanley’s Century) but the two men were certainly together on the last convoy to leave Paris.

John Winn Miller’s guest blog, Five Surprising Things I Learned Researching My World War II Novel (click here to read the blog), was extremely popular. Among others, Patrick M. Roland K., Davalene L., and Greg S. wrote us about how much they enjoyed John’s blog.

We’d love to hear from all of you at some point during 2023. We always enjoy striking up a conversation and forming long-lasting friendships.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross

My german grandfather Heinz Ahrens was the main photographer during the Whitebuss action in Sprin 1945. He was also a good aquintence to the Swedish Duke Bernadotte that often in trust my grandpa gave advise and also had logistic knowledge. Without my grandpa the whitebuss action would never have been able in time to find the secret prisons or the hidden underground camps. My grandpa was nearly 80 years not at all recognized by the Swedish Redcross or by any organisation. The Whitebuss memorial organisation in Sweden did all what they could to hide all the truth about my grandpa even when evidence and photos was presented. My mother, the daughter of the photographer is the last surviving wittness of the entire action and nobody wanna knew about her, l found it strange indeed.