Stew’s Introduction

I’m very pleased to have Mark Vaughan as our guest blogger today. Mark’s blog is about the economics of the French Revolution and I hope you connect the tag line to Marie Antoinette and her misquoted, “Let them eat cake.” Mark is a Ph.D. economist and was recently asked to put together a seminar on the economics of the French Revolution. I thought an abbreviated discussion might be interesting as this topic is rarely (if ever) discussed in the history books. While we knew the crops failed and France was on the verge of bankruptcy at the time, little do we understand the country’s overall economy and the direct effect it had on the Revolutionaries. More on Mark and how we met a little later on.

The French Revolution fascinates because of the fascinating characters and headline events. Thanks to Stew, anyone can stand in the exact spot where a shivering, prematurely gray widow, apologized to her executioner for stepping on his foot. But what if something more pedestrian than Marie Antoinette and the guillotine drove events?

Around the Revolution’s bicentennial, economists began applying their craft to late 18th century France. This research suggests basic economic principles explain much of the Revolution’s dynamics – principles like governments must pay their bills, politicians respond to interest groups, printing money causes inflation, and price controls produce shortages.

Military Competition

The economics of the Revolution start with the military competition between England and France from 1688 to 1788. Despite boasting Europe’s largest population and economy, France often flirted with bankruptcy. A tangled web of privileges and exemptions insured the First Estate (clergy) and Second Estate (nobility) bore little of an increasingly onerous tax burden. Recognizing the Third Estate (everyone else) was tapped out, Louis XVI proposed more egalitarian taxes, but the nobility wouldn’t hear of it. In frustration, Louis called an Estates General to help him square the circles.

Soon after deliberations began in May 1789, the Third Estate effectively seized control. The Revolutionaries, more interested in establishing a constitutional monarchy than balancing budgets, urged the nation to keep paying the old taxes until they got around to devising a fairer system. Unsurprisingly, as the summer wore on – with sans culottes storming the Bastille, peasants rising against lords, and the Revolutionaries abolishing tithes and feudal dues to keep the peace – tax payments slowed to a trickle.

Printing Money and Eating Cake

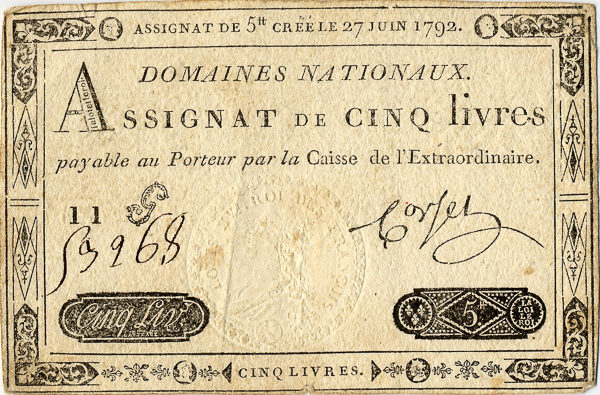

In fiscal desperation, the Revolutionaries nationalized church land in November 1789, hoping the sales proceeds would cover expenses until tax payments returned to normal. As a stopgap, the bills would be paid with paper money backed by the seized land (assignats). But, when governments start printing money to square accounts, they typically find it difficult to stop. Revolutionary France was no different, and by early 1792, the assignat had depreciated 35 percent. This inflation wreaked havoc in the market for bread (staple of French diet) as farmers and merchants began hording grain to hedge against rising prices.

Things only get worse. In part to distract the country from the economic mess, the Revolutionaries declared war against Austria and Prussia in late spring 1792. But hopes for quick victory soon evaporated, and military expenditures put even more pressure on France’s already strained finances. More assignats were printed, driving prices even higher, and soon bread was either unaffordable or unavailable. Learn more.

Price Controls and The Start of the Reign of Terror

In spring 1793, Maximilien Robespierre and the radical Jacobins saw their chance, blaming everything – rising prices, bread shortages, battlefield setbacks – on a rival faction, the Girondins, who made convenient scapegoats because of their enthusiasm for war a year earlier. Paris sans culottes lapped it up, and in May 1793, broke into the Convention to demand the Girondins’ arrest. As a further sop to the mob, the Jacobin-dominated National Convention passed the First Law of the Maximum – which established price controls on grain. The printing presses kept churning out assignats all the while, driving down their value to 25 percent of face by August.

The combination of high inflation and price controls was predictable – ever more serious shortages and increasingly desperate sans culottes. A frantic Convention tried to pacify the mob with the Law of the General Maximum – the first comprehensive wage/price controls since Diocletian in 301 AD. These didn’t work any better in France than in Rome. The economy all but imploded, and the sans culottes turned on Robespierre and his allies. Indeed, Parisians taunted him on the way to the guillotine with chants of “F**k the Maximum.”

Economists would be the first to admit much is missing from this breezy narrative. The point is not that only economics matters; rather it is the dynamics of the French Revolution become clearer when fascinating characters and headline events are seasoned with a dash of Econ 101.

Stew’s Comment

Mark has done a wonderful job of taking what can be a very complicated subject and condensing it down so even I can understand it. He’s right, a 600-word blog can’t begin to address the many influencing factors.

Meet Mark Vaughan

Mark’s Ph.D. is in economics and he has taught at Baylor, Washington University, and currently, American University. He lives with his wife in northern Virginia in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. In addition to teaching, Mark works for the federal government ensuring the peasants don’t revolt. He is doing scholarly research on economic factors in the French Revolution and will likely produce a comprehensive written chronicle focusing on this topic. He’s also a “Big fan of Stew Ross books!” – that’s a direct quote.

How Did We Meet?

Mark ran across my books Where Did They Put the Guillotine? as part of his preparation for going to Paris with his wife for their honeymoon. When he asked me for my thoughts on which walk to do (he was only given one day to devote to the French Revolution while in Paris), I suggested the one called “Marie Antoinette’s Last Ride.” I’ve included the photo of Mark standing in the courtroom where Marie Antoinette was tried. Most people would never know about this room or where to find it. There are many stops like this on the walk and that is one of the reasons why it’s my favorite walk to recommend to folks like Mark.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew

Sandy and I are frantically getting ready for our research trip to Paris in September. Although we have two weeks scheduled, there are nine separate walks (up to twelve stops per walk) and eight separate side trips. So, we must be as fully prepared as possible to maximize our efficiencies (Mark, is that an economic term?).

Someone is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thanks to Carol T. for her comments on how much she enjoys our blogs. Also, a big thank you to Joanie S. for catching my editing errors.

As I previously mentioned, our blog activity is picking up. We think this has a lot to do with our subjects being concentrated now on World War II stories. We are probably a year away from publishing the first volume of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?–A Walking Tour of Nazi Occupied Paris (1940-1944) . There are so many potential stops to take you to that culling them down has been difficult.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Copyright © 2017 Stew Ross