The war against Hitler and Germany ended in early May 1945. Europe and in particular, Germany, was in ruins. Millions of people were displaced. Estimates of displaced persons (DP) ranged between forty to sixty million including homeless, concentration camp survivors, labor camp inmates, and liberated prisoners of war.

European infrastructures were destroyed, food supplies were disrupted to the point where people continued to go hungry, coal for heating was still scarce, major transportation corridors were rendered useless, and manufacturing facilities had been bombed to the point where they could no longer function. (German factories suffered the most both from bombs and equipment pilfering by the Soviets.)

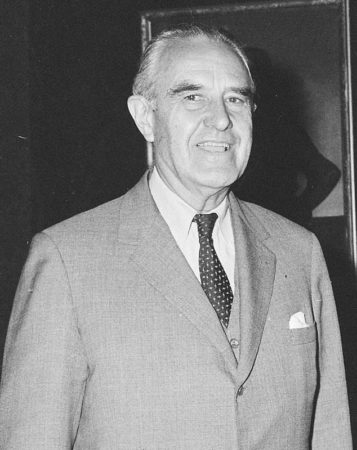

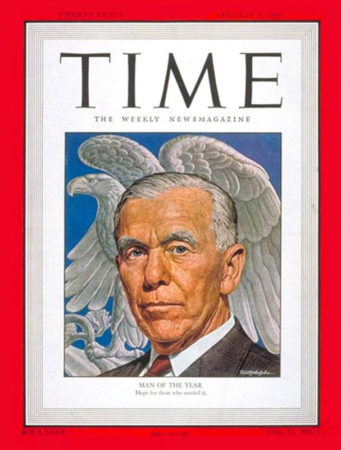

Gen. George C. Marshall (1880−1959), U.S. secretary of state, knew that it was imperative to get Europe back on its feet. The 900-lb gorilla in the room was the Versailles Treaty signed by Germany twenty-five years earlier. The terms of the treaty were so onerous that it was generally considered to be the catalyst for the emergence of Hitler and the Nazis. Gen. Marshall had a vision of the “new” Europe, and its prosperity would need to include all countries, including Germany.

The core of Gen. Marshall’s vision was comprehensive American economic assistance to the Europeans. There were two components for accomplishing this vision: creating a working plan and then the execution of the plan ⏤ in other words, getting it approved and funded by the American Congress. He acknowledged that the easy part was putting a plan together and the “heavy task” was “the execution” of the plan.

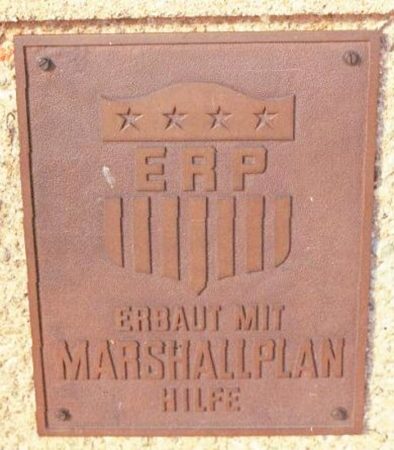

To begin the process of developing an economic aid plan, an eighteen-member council was assembled. It was chaired by Averell Harriman (1891−1986), President Truman’s secretary of commerce. The council consisted of business leaders (e.g., CEOs of General Electric, B.F. Goodrich, and Procter & Gamble), labor leaders (e.g., George Meany of the AFL), academics, and public officials. The mission of the council was to develop a report on the “limits with which” the U.S. could provide economic relief to the Europeans. The President’s Committee on Foreign Aid, or the “Harriman Committee” as it was known, provided the road map that eventually became the “European Recovery Program” (ERP) and the final bill, “The Foreign Assistance Act of 1948.”

Then and now, it is commonly referred to as the “Marshall Plan.”

REVOLUTIONARY PARIS – Volume One & Volume Two

These books are about Paris. They are about the places, buildings, sites, people, and streets that were important parts of the French Revolution. You are about to enter a journey into history beginning in 1789 at the village of Versailles with the procession of the Estates-General and ending on the Place de la Révolution with the execution of Maximilien Robespierre on 28 July 1794. This is your personal walking tour of the French Revolution as it occurred in Paris and Versailles.

Did You Know?

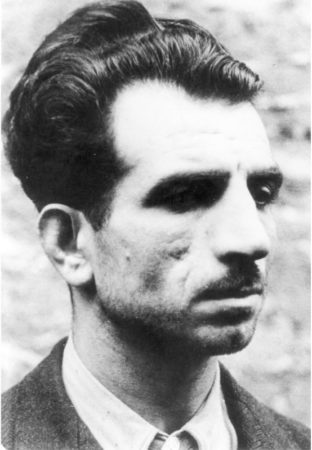

Did you know that Missak Manouchian (1906−1944) was interred in the Panthéon on 21 February 2024, exactly eighty years to the day he was executed by a Nazi firing squad at Fort Mont du Valérian?

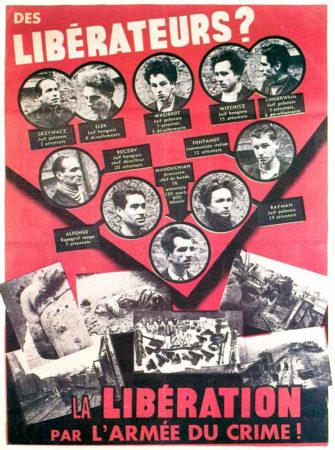

Manouchian was the leader of the FTP-MOI Manouchian Group, a 100-member resistance organization operating in Paris. The FTP-MOI résistants were predominately foreign-born Jews and unlike other Jewish resistance organizations, the Manouchian Group was armed and specialized in violent acts of sabotage, including assassinations. One member, Marcel Rajman (1923−1944), was responsible for killing SS-General Julius von Ritter. The Vichy paramilitary organization, Milice, captured twenty-three members including Manouchian and Rajman. Put on trial, all of the defendants were found guilty and sentenced to death. Twenty-two men were shot while the one woman, Olga Bancic, was deported to Germany where she was beheaded with an axe.

The Germans created l’Affiche rouge, or “The Red Poster” and plastered it around Paris. They hoped it would scare the populace and reduce resistance activity. It had the opposite effect.

Manouchian’s remains were transferred from Cimetière d’Ivry to the Panthéon. His wife’s remains accompanied him to the sacred burial site. Manouchian will join fellow résistants Jean Moulin, Josephine Baker (click here to read the blog, An African American in Paris), Pierre Brossolette, Germaine Tillion, Jean Zay, and Geneviève de Gaulle. Other former résistants are surely to follow.

Displaced Persons

The horrible consequences of World War II continued for many years after the war ended. Despite the 1943 founding of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), it was restricted from assisting prisoners of war, displaced persons from Axis countries, or ethnic Germans expelled from Eastern European nations. Other organizations such as SHAEF’s G-5 Office, or the Refugee Displaced Persons and Welfare Branch were tasked with taking care of DPs between D-Day and Germany’s surrender. Unfortunately, predictions of the numbers of DPs were severely underestimated. Two major contributing factors to the problem were Eastern European DPs who refused to return home since their country was under Soviet control and surviving Jewish refugees who refused to return to the countries that expelled them during the war. (Stalin demanded all Eastern European DPs be sent to the Soviet Union where he punished anyone suspected of collaboration with the Nazis including forced laborers and prisoners of war.)

One of the primary concerns from the large-scale refugee crisis was housing. Accommodations were located in former military barracks, factories, airports, hotels, castles, hospitals, private homes, and even partially destroyed buildings. Even former concentration camps and detention/relocation camps provided temporary housing and in Hamburg, Germany, the zoo was even used as a reception camp. On 1 October 1945, UNRRA took full responsibility for the administration of DPs in western Europe (the military provided transportation). In 1947, the UNRRA relinquished its role and the International Refugee Organization (IRO), a United Nations organization, took over those functions. By 1952, the IRO dissolved, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) assumed refugee efforts.

When the UNHCR took over, there were about 175,000 refugees left in central Europe. These were primarily people rejected by host countries because of age, inability to work, or health issues. Believe it or not, by 1960, thousands of war refugees were still waiting for housing assistance.

The Harvard Speech

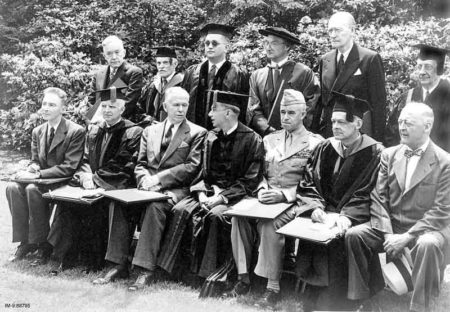

In 1947, Gen. Marshall received several invitations from universities to either be their commencement speaker or to receive an honorary degree and deliver a speech. The general chose the long-standing invitation from Harvard to accept an honorary degree and “make a few remarks and perhaps ‘a little more’ at the meeting.” No one at the time had any idea of the impact that ‘a little more’ would have on the world.

Harvard’s 286th Commencement Day took place on 5 June 1946. Gen. Marshall led the procession of honorary degree recipients (including Gen. Omar Bradley). Later that day, Gen. Marshall stood in the Harvard Yard along with fifteen thousand alumni. He was a very popular and well respected official who was trusted by both political parties. Most of the people who attended were not there because of Gen. Marshall’s remarks but because of his mere presence.

Gen. Marshall began his speech with some opening remarks but quickly got to the point. He started by pointing out the urgent need to rehabilitate the European economy. The general was always known for delivering his messages in a cool and objective manner, void of passion and this speech was no different. Gen. Marshall’s decision making process always started with what is best for the security of the United States. Right up front, he told the audience that without America’s help, Europe would face “economic, social, and political deterioration.” This would negatively impact America’s future economy and national security.

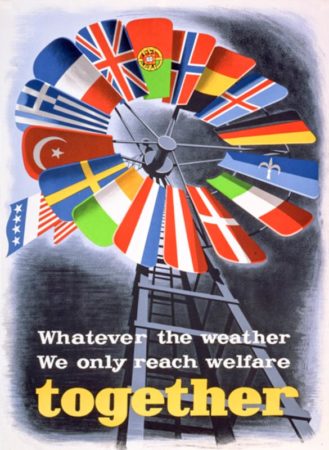

He made the case for the U.S. to do whatever it could to assist in the recovery of Europe. Gen. Marshall made sure the idea was not to single out or directed against any particular country (i.e., the Soviet Union). The plan was to fight “against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos” and assistance would be available to any country willing to assist in the recovery. The framework of the speech was defined in humanitarian and not political terms. Gen. Marshall concluded his speech with the “whole world of the future hangs on a proper judgement” by the American people.

The speech clocked in at twelve minutes, ten seconds and very few at the time realized its significance.

The Marshall Plan

In addition to the Harriman Committee, two other studies were conducted. The Council of Economic Advisors (“Nourse Committee”) and the National Resources and Foreign Aid (“Krug Committee”) prepared separate reports but largely agreed with the Harriman Committee’s findings that without providing aid to Europe, the United States would likely suffer economically in the long-term. The five goals of the Marshall Plan were (1) rebuild war-torn regions, (2) remove trade barriers, (3) modernize industry, (4) improve European prosperity, and (5) prevent the spread of Communism.

The three most important findings from these three committees were determination of limits that the U.S. could safely provide assistance, anticipating problems, and making the Europeans responsible for asking for assistance. One of the key discussions was to decide whether this program would be one of charity or a cooperative effort to bring about economic recovery. To the committees’ credit, the latter was chosen. There were conditions to accepting money from America. The six primary requirements were (1) develop multilateral payment and trade within Europe, (2) move toward currency convertibility, (3) move toward eliminating discrimination against U.S. imports, (4) encourage reductions in public spending, (5) relax government controls such as rationing, and (6) increase exports to the U.S.

Five months after the Harvard speech, all the preparatory work had been completed. By early November 1947, the framework of the ERP had been developed. At this point, the ball was in the European court so to speak. America waited to see if the Europeans would unite and request joint assistance and if so, how much each country would require. Another big question was whether the Soviet Union and its satellites would participate. It didn’t take long for Truman and Marshall to find out.

As expected, the Soviets dragged out the process and proved to be a negative influence. Stalin gave permission for his representative to obstruct and prevent the Marshall Plan from being implemented in Russia or the satellite countries. (Stalin’s primary concern was losing control over his “buffer zone.”) After the Soviets exited the discussions, sixteen European nations began the smooth process of unanimously approving an organizational structure and agenda. The “Committee of European Economic Cooperation” (CEEC) was established. Back in Washington, Gen. Marshall relied on his undersecretary of state, Robert “Bob” Lovett (1895−1986) to take over the day-to-day running of the state department including shepherding the Marshall Plan to its conclusion. In fact, Gen. Marshall never got involved in the minutiae and by 1948, his health and stamina were suffering. (He resigned as secretary of state in January 1949 due to ill health.)

Despite the media informally naming the economic assistance program the “Marshall Plan,” President Truman’s advisor, Clark Clifford (1906−1998), suggested it be called the “Truman Concept” or the “Truman Plan.” President Truman rejected Clifford’s ideas. It was an election year in 1948, Congress was solidly Republican, and Truman was not well regarded. He knew any proposals put forth with his name on it would quickly die in committee. So, the president decided to name it after Gen. Marshall. He told Clifford, “I’ve decided to give the whole thing to General Marshall. The worst Republican on the Hill can vote for it if we name it after the general.” The president’s prediction was proven correct.

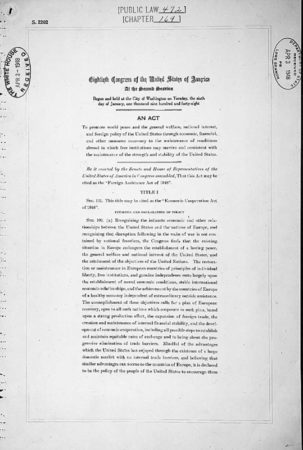

In October 1947, the bipartisan “Committee for the Marshall Plan” was formed for the purpose of promoting the plan’s passage. Chaired by Henry Stimson (1867−1950), members included Dean Acheson, Allen Dulles, Alger Hiss, and Mrs. Wendell Willkie. Expectedly, there was opposition to the economic assistance plan. Postwar anti-Communism, isolationism, and the conservative movement led by the Republicans produced congressmen like Howard Buffett (R-Nebraska) to call the plan “Operation Rathole.” Stimson’s committee disbanded almost immediately after the ERP bill was approved and signed into law by President Truman on 3 April 1948.

The Cost

The original cost proposed by the CEEC totaled $28 billion. Their “shopping list” was rejected by Lovett and Marshall as unrealistic. President Truman agreed and the CEEC was pressured to come up with a new amount. In September 1947, the CEEC submitted its new request of $17 billion. The Krug and Nourse Committees determined the $17 billion would not endanger America’s national defense or vital resources. Even the secretary of defense, James Forrestal (1892−1949) supported this amount.

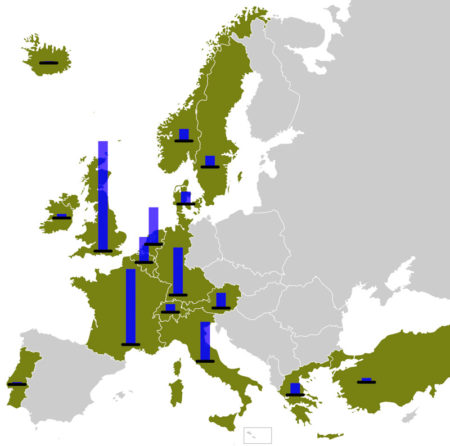

Between 1948 and 1952, about $13.3 billion (more than $130 billion in today’s currency) was distributed among eighteen European countries. Great Britain was the largest recipient at $3.2 billion followed by France ($2.7 billion), West Germany ($1.4 billion), Italy ($1.5 billion), and the Netherlands ($1.1 billion). Combined payments to Greece, Austria, Belgium/Luxembourg, Denmark, Turkey, Norway, Ireland, Sweden, Portugal, Iceland, and the European Payment Union totaled about $3.4 billion. Additionally, grants and loans totaled about $13.3 billion.

In the end, the amount of money spent via the Marshall Plan was relatively insignificant. The cost of World War I was $20 billion, or $253 billion in 2008 dollars while World War II’s cost totaled about $296 billion ($4.1 trillion in 2008 dollars ⏤ today, America’s annual revenue is about $3.0 trillion). There are those who believe Europe would have “looked” the same without the Marshall Plan. In fact, the countries implemented and executed their own independent recovery programs. For twenty-years, Western Europe experienced unparalleled growth and prosperity. How much of that was due to the funding under the Marshall Plan? One economist believes it provided the “critical margin” upon which other sources of funding depended on (e.g., easing trade barriers). Certainly, from a psychological standpoint, the Marshall Plan was extremely successful. Traveling around Europe today, one can see tributes to the plan. So like the Allied invasion of Normandy, the Marshall Plan isn’t totally forgotten.

Passage

In hindsight, it’s easy for us to unconditionally support the costs of the bill against the benefits. However, back then, there were very strong feelings about the spread of Communism as well as isolationism. Remember, World War II had only ended two years earlier when Gen. Marshall proposed the concept of the plan. Americans wanted to return to normalcy and the economic and human cost of the world war was enormous. It’s no wonder the isolationist movement was so strong. Isolationist Republicans such as Senator Robert Taft (R-Ohio) and Senator Kenneth Wherry (R-Nebraska) argued against supporting countries with socialist governments while the conservative internationalists led by Senators Arthur Vandenberg (R-Michigan) and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. (R-Massachusetts) believed the plan would stem further Soviet expansion. Fortunately, Vandenberg and Lovett’s efforts were successful. After approving temporary funding to get Europe through the cold winter of 1947/48 and cross-country trips by Marshall and others to present their case to the public, the time finally came to approve the ERP.

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee approved the bill in February 1948 to go to the full Senate for floor action. On 14 March, the Marshall Plan was approved with a vote of 69 to 17 opposed. Thirty-one Republicans (including Sen. Taft) and thirty-eight Democrats voted for the bill. Now the debate shifted to the House of Representatives. On 20 March, a narrow vote of 11-8 ensured the bill got out of committee with a recommendation it be approved. A tipping point came when former President Herbert Hoover wrote a letter reversing his initial opposition and fully endorsed the plan. On the last day in March, the bipartisan House voted 329 to 74 in favor of the bill.

Credit should go to Vandenberg for the bipartisan support in Congress. The general public was in general support of the plan as were multiple special interest groups. Mainstream media, including conservative publications, lined up to support the ERP.

Despite including the Soviet Union as a potential recipient of the ERP funds, a downside to the ERP was the Stalin’s perception that the plan was created and implemented as a way of creating a Western Bloc and dividing Europe into East and West. Another major Soviet concern was the unacceptable possibility of a unified Germany under Allied control. The economic plan was seen by Stalin as a way to “enslave” the Germans and turn them against the Soviet Union. The result was that two years after the Cold War was ushered in after Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech, Stalin and the Soviets became further entrenched in their battle against the Western powers click here to read the blog, Logistics Genius).

There were three “non-negotiables” taken into consideration by the framers of the Marshall Plan that contemporary American politicians should pay more attention to when giving away money. First, what will be the effects on the security of the United States; second, can the U.S. afford it; and finally, require tangible conditions if approved.

In hindsight, no one can deny that the Marshall Plan did not accomplish the five goals set out in 1947.

Next Blog: “Jacques the Ripper”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Bradley, Omar N. and Clay Blair. A General’s Life. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983.

Bryan, Ferald J. George C. Marshall at Harvard: A Study of the Origins and Construction of the ‘Marshall Plan’ Speech. Wayback Machine, 2020.

Frank, Matthew and Jessica Reinisch (editors). Refugees in Europe, 1919−1959: A Forty Years’ Crisis? London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.

George C. Marshall Foundation. Click here to visit the web-site.

Harry S. Truman Presidential Library.Click here to visit the web-site.

Marshall, George. The Marshall Plan Speech. The George C. Marshall Foundation. Click here to visit the web-site. Click here to watch the speech.

McCullough, David. Truman. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 1992.

Roll, David L. George Marshall: Defender of the Republic. New York: Dutton Caliber, 2019.

Steil Benn. The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

Weissman, Alexander D. Pivotal Politics ⏤ The Marshall Plan: A Turning Point in Foreign Aid and the Struggle for Democracy. History Teacher 47.1 (2013): 111-129. Click here to read the article.

Wyman, Mark. DPs: Europe’s Displaced Persons, 1945−1951. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998.

I highly recommend you click on the YouTube link above to listen to Gen. Marshall giving his “Marshall Plan” speech at Harvard. The transcript of his speech can be read here.

The Truman Presidential Library online collection consists of original Marshall Plan documents from 1946 onward. Click here to visit the web-site.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are looking forward to our trip to Japan in several weeks. While Sandy traveled to Japan several times for work (many years ago), I have never been there. Like many Americans, we enjoy Japanese cuisine, especially good sushi (and sashimi). So, one of our goals is to experience the sushi restaurants in Tokyo. These are typically very small establishments with only six to eight seats. Our expectation is to have a much wider range of fish to choose from. I’ll let you know how it goes after we return.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thanks to Steve Williams for reaching out to us regarding our blog, New Forest Airfields (click here to read the blog) Steve is a trustee for the museum and wanted all of us to know that he has launched a new website, click here. For those of you wishing to visit the museum and former RAF airfield sites, Steve’s website has quite a bit of information that will add value to your visit. This year marks the 80th anniversary of D-Day and these airfields are a historical part of that monumental event. If you are planning on visiting, please don’t hesitate to contact Steve at nfww2airfields@gmail.com. I know he will be pleased to see you.

I’d like to thank Rupert S. for pointing out my error on the blog, The de Facto Traitor (click here to read). I mistakenly wrote that Tsar Nicholas II was the cousin of King Edward V. Oops! Nicholas II was the cousin of King George V. I was more than four hundred years off. Thanks, Carl, for pointing that out. It wasn’t my first mistake and won’t be the last. (At least I got the image caption correct.)

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Shepherd.com is like wandering the aisles of your favorite bookstore.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Check out Stew’s new bookshelf on the French Revolution.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2024 Stew Ross

Stew:

Be careful during your visits to seafood restaurants in Japan. I have been there 200+ times (almost all for business) and inevitably someone suggests that we order fugu fish. Fugu is a “puffer” fish and can be extremely poisonous if not cleaned and cooked (or eaten raw) with professional skill by licensed experts. Even when it has been professionally prepared and is no longer deadly, it is a pretty tough and chewy piece of fish that is not worth the tiny risk as cuisine. There are many better choices, and I got away with not being considered a “wimp” by saying I have had it many times and it is not my favorite fish.

Now that I am retired I miss Japan very much. You will love it.

Carl

Hi Carl; always good to hear from you. I appreciate the heads up on the fish. We were aware of the dangers from eating puffer fish. Glad we know what the Japanese name is for it. STEW

Another excellent and timely article. Sadly, it’s no surprise that we still have a group of Republican politicians that see no benefit to the United States in continuing to work together with our European allies in order to maintain our own national security. I remember the Marshall Plan. Of course, I was born in 1946. Most people these days don’t have absolutely no clue how instrumental it was in helping to European nations to recover from the devastation caused by World War II. Thanks for reminding us Stew.

Hi Greg; thanks for your comments. STEW