Posting this blog on the fifth of each May has become a tradition for me.

Liberation Day (also known as Freedom Day) for the Netherlands (Holland) was 5 May 1945. Canadian forces along with other Allied forces were able to obtain the surrender of German forces in the small Dutch town of Wageningen. This led to the complete German surrender and liberation of the country. The Netherlands was one of the last European countries to be liberated. Two days later in Reims, Generaloberst Alfred Jodl signed the document for the unconditional surrender of the German armies.

Did You Know?

Did you know that for the past thirty years, “Wreaths Across America” has been responsible for placing holiday wreaths on thousands of American military graves? The secularist non-profit organization, “The Military Religious Freedom Foundation” (MRFF) has declared this tradition to be “unconstitutional, an atrocity, and a disgrace.” They believe the wreath-laying to be the “desecration of non-Christians veterans’ graves.” The MRFF says, “. . . forcing the non-Christian dead who didn’t celebrate Christmas in life to celebrate it in death.” Perhaps we should all take the position that the wreaths are really meant to celebrate, remember, and honor American veterans, fallen or otherwise.

Netherlands American Cemetery (Margraten)

There is a cemetery near Maastricht. It is the final resting spot for 8,301 American soldiers and a memorial for 1,722 men missing in action. They were the casualties of Operation Market Garden (17–25 September 1944) and other battles aimed at liberating Holland. Operation Market Garden was a failed Allied attempt to liberate Holland while on their march to Germany and Berlin. Other military cemeteries are located nearby for the British and Canadian men who did not survive the battle. Learn more about Operation Market Garden here.

Four generations of Dutch families have adopted every man who perished in the battle. Each man’s grave is kept up and decorated by their adopted family. Every Memorial Day, American Embassy staff greets the Dutch families as they arrive at the cemetery to lay down flowers and wreaths. Even a portrait of their adopted soldier sits in their respective homes.

“Face of Margraten” was started by a young Dutch man to preserve the image of each of the fallen soldiers. About eight thousand images have been collected and every two years, each grave is marked with the image of its occupant.

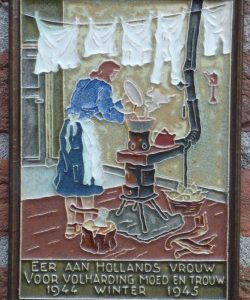

Hongerwinter

The Dutch railway workers called a strike before the battle began believing it would increase the chances of success by the Allied forces. The Allied efforts failed and Holland would have to wait another seven months to be liberated. In retaliation for the rail strike, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the Nazi leader in charge of the German occupation of Holland, refused to allow any food into the country. Holland was literally being starved to death during the 1944-1945 Hongerwinter (winter of hunger). More than 20,000 people died that winter of starvation. By the end of the war, subsistence was four hundred calories per person. Seyss-Inquart was one of the Nuremberg defendants tried, convicted, and executed for various war crimes, including those committed in Holland. Watch a news clip here.

Liberation Day

Every May on the fifth, Liberation Day is celebrated in Holland. For two minutes, everything and everybody stops while the church bells ring. At the end of the day, a concert is held. Beginning in 1965 (the 20th anniversary of the liberation), Nino Rossi’s taps called “Il Silenzio” is played as the final piece of the concert.

As a 10-year-old living in the city of Wassenaar during the 1960s, I’ll never forget stopping on the street wherever we were when the church bells began to ring. We stopped talking and listened to the bells ring for 2 minutes—every year.

I invite you to click on the following link and listen to a 13-year-old Dutch girl, Melissa Venema, play “Il Silenzio” during the 2008 concert celebrating the liberation of Holland. The Royal Orchestra of the Netherlands backs her up. It is very moving—at least for the former 10-year-old boy growing up in Holland.

Grab a tissue before you listen to this. I do.

President’s Speech

“On this peaceful May morning we commemorate a great victory for liberty, and the thousands of white marble crosses and Stars of David underscore the terrible price we pay for that victory. For the Americans who rest here, Dutch soil provides a fitting home. It was from a Dutch port that many of our pilgrim fathers first sailed to America. It was a Dutch port that gave the American flag its first gun salute. It was the Dutch who became one of the first foreign nations to recognize the independence of the new United States of America. And when American soldiers returned to this continent to fight for freedom, they were led by a President (Roosevelt) who owed his family name to this great land.”

George W. Bush

President of the United States

28 May 2005

Netherlands American Cemetery

Recommended Reading and Viewing

Levin, Joseph E. (Producer). A Bridge Too Far. United Artists, 1977.

Matzen, Robert. Dutch Girl: Audrey Hepburn and World War II. Pittsburgh, PA: GoodKnight Books, 2019.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books (in our case, it is Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?). The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross