When we usually think about the contributions women made during World War II, it is typically nurses and “Rosie Riveters” who come to mind. While I’ve previously discussed women serving as foreign spies in the occupied countries (read Women Agents of the SOE here), cryptanalysts (read Unit 387 & Hillsdale here), and pilots ferrying planes from manufacturing facilities to domestic air bases (read Killed In The Service Of Her Country here ), there were other jobs equally important (and dangerous) to the war efforts which American women filled. While today we don’t agree with this, there were two fundamental beliefs at that time: women should not be allowed in uniform let alone go into combat and all troops had to be segregated. However, regardless of color and gender, many of the women who stepped up to volunteer for the military (the idea of drafting women was dropped immediately after it was suggested) filled roles which allowed more men to go into combat. Today, you will meet the only unit of all-female soldiers to be deployed overseas during World War II and it was an African-American battalion in the Women’s Army Corps.

August Historical Events

This month in recorded history:

| 2 August 216 BC | The great Carthaginian general, Hannibal, defeated the mighty Roman Empire army on the battlefield at Cannae, Italy. His army had crossed the Alps and caught the Romans in a trap. This was his third defeat of the Romans and so, Hannibal was able to complete a military “hat trick.” |

| 3 August 1492 | The Pinta, Niña, and Santa Maria set sail from the Andalusian port of Palos de la Frontera in the early morning. The Genoese navigator, Christopher Columbus, had finally convinced a European royal family (i.e., Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain) to bankroll his search for a new trade route around Africa. Thirty-six days later, he landed in the Bahamas. Columbus never made it to Asia and I’m sure Ferdinand and Isabella never received the expected return on their investment. |

| 1 August 1944 | Date of Anne Frank’s last entry into her diary. Anne was arrested three days later by the Gestapo. She died at the age of fifteen on 15 March 1945 at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. |

| 25 August 1944 | Paris is liberated! (how could I leave this out?) |

| 6 August 1945 | The first atomic bomb is dropped on Hiroshima. It was followed three days later by the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki (I wish I could leave these out). |

| 14 August 1945 | Japan surrendered, and World War II ended ⏤ “Victory in Japan” day or, V-J Day. |

| 13 August 1961 | “Barbed Wire Sunday” was the day Germans living in Berlin woke up to find their city had been divided by barb wire which effectively blocked movement between East and West Berlin. Later, the Berlin wall would be erected. |

| 28 August 1963 | The “March on Washington” took place as 250,000 people attended a Civil Rights rally in Washington, D.C. where Martin Luther King, Jr. made his speech, I Have a Dream. Josephine Baker was the only woman invited to make a speech (read An African American in Pre-WWII Paris here.). |

Women’s Army Corps (WAC)

The WAC was the women’s branch of the United States Army. It was created in May 1942 and converted to active duty on 1 July 1943. President Roosevelt authorized a maximum recruitment goal of 25,000 for the first-year but that number was almost immediately exceeded, and the goal was raised to 150,000 (the War Department refused to increase this number even though many high-ranking generals, including General Douglas MacArthur, saw the benefits of women joining the WAC). Along with nurses, WAC soldiers were the only women to serve in the army ⏤ other military service branches had similar women’s units. In the beginning, they were trained as switchboard operators, mechanics, and bakers. These three specialties were later expanded to include postal clerk, driver, stenographer, and clerk-typist. While there was resistance by some of the senior commanders and general rank and file, the WAC was supported early on by General Hap Arnold and his United States Army Air Forces (the predecessor to the modern-day USAF). Refer to our blog Killed In The Service Of Her Country here. Approximately 150,000 women served in the WAC during the war ⏤ mostly stateside but also in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific. It is estimated that these women were responsible for releasing seven divisions of men for direct combat assignments (divisions range from 10,000 to 18,000 soldiers). WAC soldiers were paid the same as their male counterparts and the insignia designations were the same. They were allowed to wear officer insignias which were on par with the ranks of second lieutenant up to colonel (nurses weren’t granted those ranks until 1944). The WACs did everything a male soldier did except carry a gun and engage the enemy.

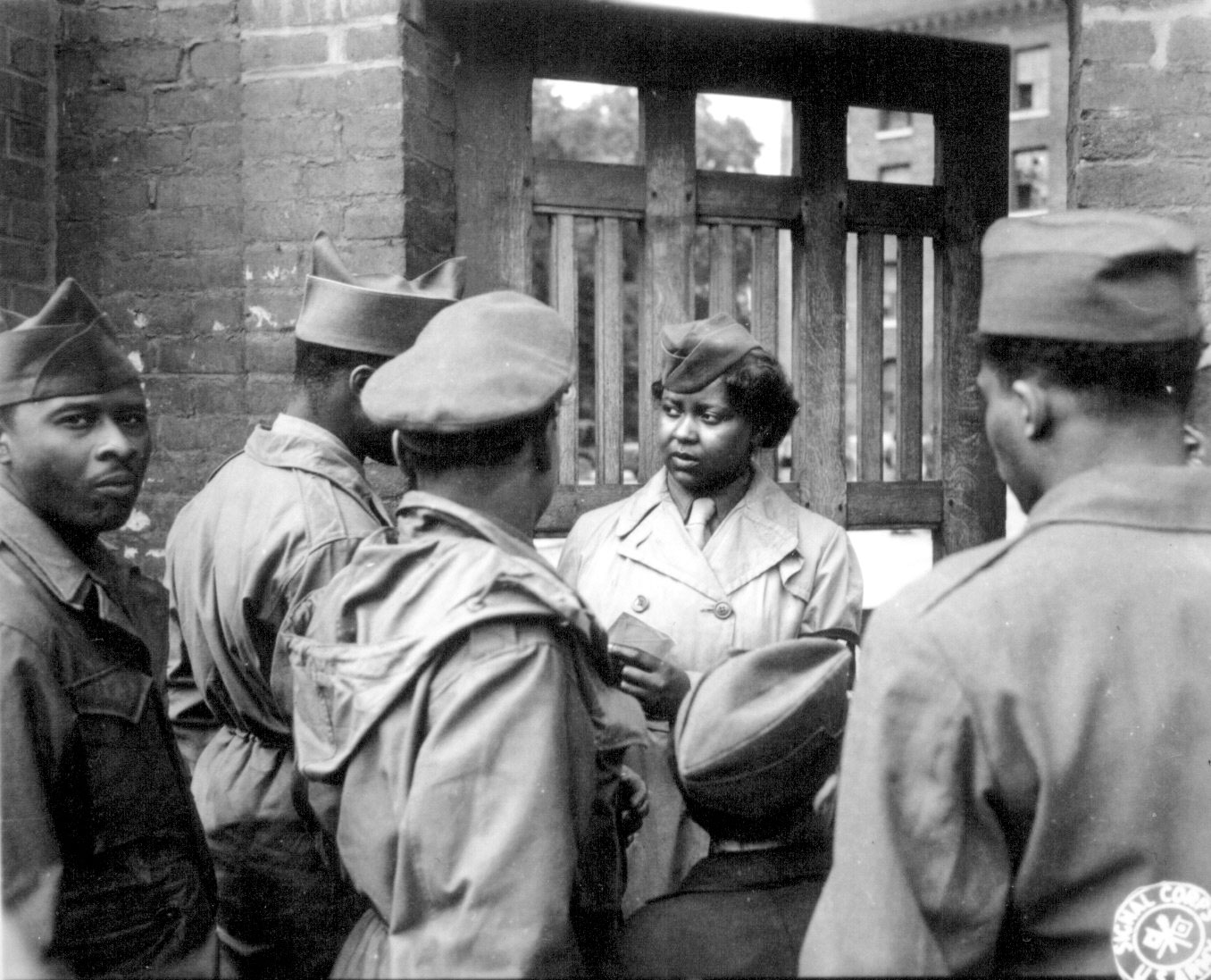

While African-American women in the WAC experienced the same segregation issues as the men during the war, they were not segregated during training and some of the billets (i.e., quarters) accepted women of all races. Regardless of color, WAC soldiers were trained in the same specialties. The army’s goal was to recruit ten percent African-Americans for enlistment in the WAC, however, they only reached a maximum five percent enlistment. The only all-female military battalion shipped overseas was the Women’s Army Corps 6888 Central Postal Directory Battalion. It also had the distinction of being the first female African-American battalion in the U.S. Army. Since a limit of ten percent of the Women’s Army Corps could be African-American, the soldiers began calling themselves the “Ten-Percenters.”

The Six Triple Eight

Forty African-American women were originally selected for the WAC in 1943. Despite initial slow recruitment, by November 1944, more than 817 enlisted women and thirty-one officers formed the 6888th battalion, commonly referred to as the “Six Triple Eight.” Major (later Lieutenant Colonel) Charity Edna Adams (in 1949 with her marriage, became Charity Adams Earley) commanded the Six Triple Eight. The soldiers underwent training at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. By January 1945, their training was completed, and they were shipped off to Camp Shanks in New York where they departed for Europe on 3 February 1945. Coming under direct fire during the 11-day voyage, the first ship arrived in Glasgow, Scotland.

“No Mail, Low Morale”

The mission of the Six Triple Eight was to go through the stacks of mail and packages in a Birmingham, England warehouse that had accumulated since D-Day. The Army estimated it would take at least six months to clear all the mail. Major Adams and her officers created a new and efficient system for processing the mail. Utilizing three shifts per day, the soldiers processed 65,000 pieces of mail per shift. The battalion’s motto was “No mail, low morale.” Within three months, all of the backlog mail had been disposed of and the Six Triple Eight had solved the Army’s huge mail problem. It was an unprecedented success. In fact, the brass was so impressed that they sent the 6888th to France one month after VE Day (8 May 1945) to deal with a similar problem.

Landing in Le Havre, the shocked women encountered an entire city in ruins. Their destination was Rouen where the battalion was invited to participate in a victory parade. The French cheered them on as they had African-American entertainers during the interwar period or, the years between the world wars (read An African-American in Pre-WWII Paris here). The soldiers worked with French civilians, male and female, as well as German POWs to eliminate a large backlog of mail dating back three years. As before, the army brass expected them to take six months to work through the pile, but the 6888th once again, exceeded expectations. The battalion was transferred to Paris in October 1945 and many of the women began to be sent back to the States and discharged. By February 1946, the remaining members of the 6888th returned to the States and discharged at Fort Dix, New Jersey. Watch a film clip about Major Charity Adams here.

The battalion’s accomplishments did not go unnoticed. The General Board, United States Forces European Theater acknowledged that the military services of females, regardless of color, were indispensable to the war effort.

Segregation

The African-American women of the 6888th experienced the same discrimination as their male counterparts. Their quarters, mess hall, and recreational facilities were segregated by race and gender. They also encountered hostilities from the African-American male soldiers as these men shared the same prejudice as most Americans with respect to believing women should not be serving in uniform. In London, Major Adams’s troops were not allowed inside the Red Cross clubs. She refused to accept this and led her soldiers in a boycott of the clubs. The battalion set up its own mess hall, hair salon, and recreational facilities. While in England, the women were treated with respect by the locals and found them to be very polite and welcoming (the soldiers were routinely invited into the locals’ homes for afternoon tea). Unfortunately, throughout the existence of the 6888th, the battalion’s superior officers were constantly complaining about the efficiencies, production levels, race-mixing, and other minor issues. As an aside, I find it interesting and ironic that here we were fighting Hitler and the Nazis while sharing one of their viewpoints (i.e., racial separation and race-mixing).

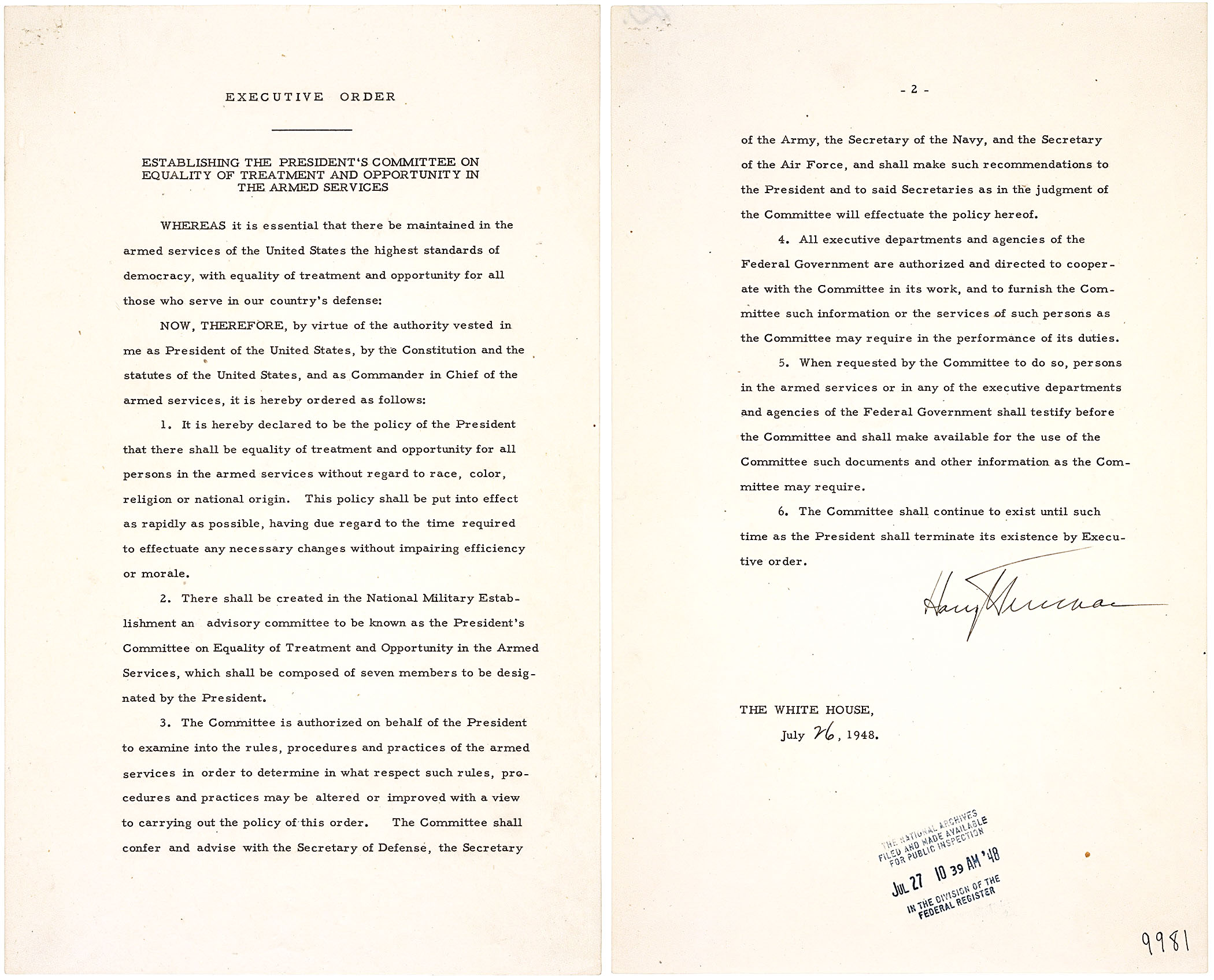

The WAC was disbanded in 1978 when all units were fully integrated into male units. By 1994 under the Clinton administration, women were granted the right to enter combat. The last WAC, Chief Warrant Officer 5 Jeanne Pace, retired in 2015 after a 43-year career in the military.

Lieutenant Charity Adams Earley

Charity Adams Earley (1918-2002) was the first African-American woman to become an officer in the WAC. By the end of the war, she had been promoted to lieutenant colonel becoming the highest ranking African-American woman officer in the army. Charity enlisted in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (the predecessor to WAC) in July 1942 and immediately, her superiors saw someone who was a born leader. Charity was put in charge of improving efficiency and job training among her other duties. By December 1944, Major Adams was leading the 6888th Battalion. While stationed in Birmingham, Charity fought against discrimination and focused on raising the morale of her troops. At one point, a general told her that he was going to send a white first lieutenant in to show her how to do her job. Her response was “Over my dead body, sir.” She was threatened with court-martial, but the matter was ultimately dismissed. Charity encouraged her soldiers to mix with the locals as well as all the men who returned from the front on leave. Her goal was to create comradeship and lessen the strain of racism. Charity left the WAC in 1946 for a position at the Pentagon. Her later years were spent in volunteering and as one might suspect, Charity Adams Earley was the recipient of numerous awards and honors including the Smithsonian Institute’s “110 Most Important Black Women: Black Women Against the Odds.”

Watch a video on Charity Adams here.

Recommended Reading and Viewing

Earley, Charity Adams. One Woman’s Army: A Black Officer Remembers the WAC. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1995.

Interview with Pfc. Elizabeth Bernice Barker Johnson. Watch it here.

National Museum of the United States Army. Link here.

Putney, Martha S. When the Nation Was in Need: Blacks in the Women’s Army Corps During World War II. Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1992.

The recommended books were written by two members of the 6888th and are first-hand accounts of the battalion.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

I recently learned that my best friend in high school passed away in March 2019. Duncan Campbell was also my best man at our wedding forty-one years ago.

I hesitated putting this news in the blog, however, I realized that perhaps some of our subscribers and regular readers of our bi-weekly blog might be people whom I knew in high school. If so, they likely knew Duncan either directly or indirectly and it’s possible they had not heard of his passing. He was an extraordinary person and I feel very lucky to have known him.

Duncan, I hope you rest-in-peace my friend.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

As always, I’d like to thank those of you who write us about our blogs. Many times, we are asked questions about a particular blog, its subjects, or events. Several of you read the blog, I Was Looking Forward to a Quiet Old Age (read here), and had questions about Kitty. Steven asked us if we knew what ever happened to Kitty and her son. Another one of our readers was wondering where I got my information about Kitty’s fate (I mentioned she survived).

There is virtually no information about Kitty (her real name was Catherine Bonnefous) and her life after the war. She was arrested by the Gestapo in mid-December 1940, put on trial in March 1941, and sentenced to death. According to the book Lindell’s List: Saving British and American Women at Ravensbrück by Peter Hore (Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2016), Kitty’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. She survived the next three years being shuffled around various prisons and concentration camps. Kitty was liberated in February 1945 by the Soviet Army but suffered from their brutalities including likely being raped.

Further information was found through Fondation Pour La Memoire de la Deportation (Foundation for the Memory of the Deportation). Kitty’s name was part of a log that reflects her status as a “Nacht und Nebel” (Night and Fog or NN) prisoner (read Night and Fog here) and the camp she was liberated from was Jauer. The Jauer camp would have been the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, a collection of camps located between the towns of Jauer (now known as Jawor) and Striegau (Strzegom). It was known as one of the camps where NN prisoners were sent. Jauer was also a camp which provided slave labor to various German manufacturing plants. While I don’t know this for sure, but if Kitty was strong enough to work, she might have survived as a laborer in one of those plants. Kitty was born in 1886 and would have been fifty-nine when liberated. Surviving four years of Nazi imprisonment was certainly the exception and it is likely she would have had severe health issues upon release (similar to Etta). The date of her death is unknown. Unfortunately, I don’t have any information about her son.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Copyright ©2019 Stew Ross