How many of you have read The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness Orczy? Probably not many. It’s the story of the wealthy but foppish Sir Percy Blakeney who leads a double life. He is an accomplished swordsman, master of disguises, escape artist and as the “Scarlet Pimpernel,” Sir Percy rescues French aristocrats from the guillotine blade during the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror.

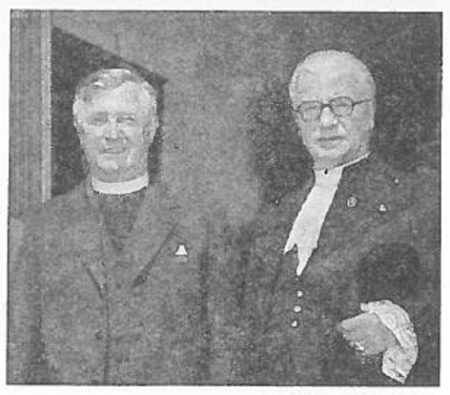

Today, we are going to focus our attention on a Scottish pastor who led the Paris parish for the Church of Scotland. Rev. Dr. Donald Caskie’s wartime exploits for rescuing downed Allied airmen and leading them to safety through the Pat O’Leary escape line earned him the nickname, “The Tartan Pimpernel.”

I will be the guest speaker for Bonjour Paris on 6 December 2023 for a Zoom presentation to their members and others. The topic will be “Walking History: In the Footsteps of Marie Antoinette” and I will take you on a walk along the exact route in Paris that the queen’s tumbrel took to the guillotine. I invite you to join us for the discussion and slide show.

Bonjour Paris (click here to visit the web-site) is a digital website dedicated to bringing its members current news, travel tips, culture, and historical articles on Paris. I have been a member for more than ten years and have found its content to be quite interesting, practical, and entertaining.

I will have a direct link to sign up for my presentation at a later date. There is no cost to Bonjour Paris members and €10,00 for non-members. The time of the live presentation on 6 December will be 11:30 AM, east coast time.

Did You Know?

Did you know I could probably write enough blogs on World War II traitors to fill an entire year? Today, I decided to call-out a particular British traitor who was quite dastardly and frankly, a lousy human being. Harold Cole (1906−1946) ⏤ a.k.a. Harry Cole, Paul Cole ⏤ began his criminal career as a teenager. Released from prison shortly after the war began, Cole enlisted in the British army and was stationed in France. Considered handsome with an appealing personality and sharp wits, Cole was never without female company. It didn’t take long before he was caught stealing from the army and jailed. Escaping, Cole was apprehended and thrown into jail once again. As the Germans overran France, Cole was released by the military but rather than returning to England, he remained in France.

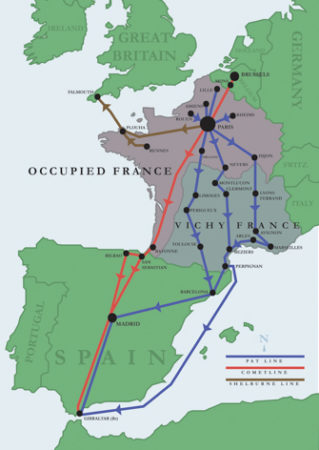

In the summer of 1940, Cole established his alias as Paul Cole, and formed a group of men and women to help British soldiers get out of France. Many people, including Nancy Wake (click here to read the blog, The White Mouse), saw through Cole’s masquerade and broke off contact with him. Cole visited Marseille in February 1941 and Ian Garrow appointed him to run the operations of the Pat O’Leary line in northern France. Cole and his group were considered very efficient in transporting escapees to Marseille and despite MI9’s knowledge of Cole’s past, he was allowed to continue with the Pat line. Eventually, Cole began spending most of his time in Marseille collecting British money for his efforts.

Rev. Caskie first met Paul Cole when the Pat Line operative personally delivered nine men to the reverend’s Marseille mission. Right from the beginning, Rev. Caskie had suspicions about Cole and whether he was an infiltrator. Soon after that meeting, men began to die on the final leg of their journey to freedom. It turned out Rev. Caskie was correct in his assessment.

Garrow and other Pat line leaders became aware Cole was keeping the money and not paying his people. They confronted Cole on 1 November 1941, locked him in a bathroom, and contemplated whether to execute him. Cole managed to escape and somehow ended up in the hands of the Gestapo (there is some speculation that he had been a German agent all along). He wrote out a complete statement about the Pat Line including a description of everyone he knew in the resistance organization. Immediately, the Gestapo began arresting the résistants. Cole escaped from Gestapo control and went to Paris and Lyon. By then, he was a marked man by both the resistance and the Germans. Cole was arrested by Vichy police in Lyon and charged with espionage. Convicted and sentenced to death, the traitor was later given a reduced sentence to life in prison. Even though the Germans didn’t trust him at this point, Cole was released during the winter of 1943/1944.

Cole went to Paris and began working for the head of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), SS-Stormbannführer Hans Josef Kieffer (click here to read the blog, Avenue Boche). By early August 1944, it became clear the Allies were rapidly marching toward Berlin and would likely liberate Paris on their way to the German capital. Cole and Kieffer fled Paris on 17 August and disguised themselves as a British officer and German policeman, respectively. Surrendering to the Americans in Germany, Kieffer was released, and Cole was given an American uniform and identification card. (Kieffer would later be arrested, tried as a war criminal, and executed.) Cole ended up in the French sector of Germany impersonating an intelligence officer. He interrogated Nazis and formed a group of bandits to do his dirty work of stealing, torturing, and executing prisoners.

British intelligence caught up with Cole after his ex-mistress slipped up and revealed his whereabouts. Imprisoned, Cole once again escaped. A massive search was conducted, and Cole was found in a bar where he was killed in a shoot-out on 8 January 1946. The man who identified Cole’s body was Albert Guérisse (a.k.a. Pat O’Leary).

MI9’s Airey Neave (1916−1979) said, “(Cole) was among the most selfish and callous traitors who ever served the enemy in time of war.” The liaison between MI6 and MI9, James Langley (1916−1983), said Cole was “a con man, thief and utter shit who betrayed his country to the highest bidder for money.”

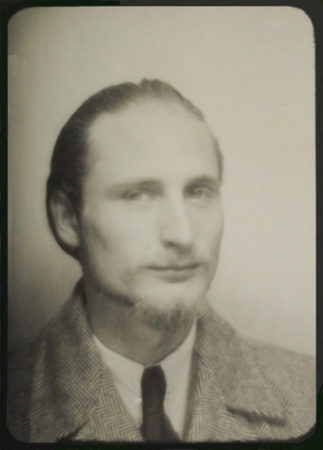

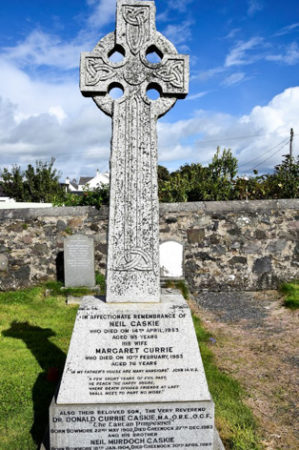

Let’s Meet Reverend Dr. Donald Currie Caskie

Donald Currie Caskie (1902−1983) was born in Bowmore on the Scottish island of Islay, about 150 miles due west of Glasgow. Donald’s parents were Neil Caskie (1862−1953) and Margaret Currie Caskie (1875−1953) and he had six brothers and one sister. Donald’s family were crofters (i.e., tenant farmers) and although poor, they managed quite well. His education began at Bowmore School followed by Dunoon and then earning his master’s in arts in 1926 followed by a degree in divinity at New College.

Ordained in 1932, Rev. Caskie’s first church assignment was three-years at Gretna Green, north of Carlisle. In 1935, he was transferred to Paris to take over the Scots Kirk Paris. As Hitler and his party gained strength in the mid- to late-1930s, Rev. Caskie’s sermons from the pulpit of Scots Kirk grew increasingly heated with denouncements of Hitler and the Nazis. By the time the Germans invaded France in May 1940, Rev. Caskie knew he was a marked man and would need to eventually flee Paris.

The Scots Kirk Paris

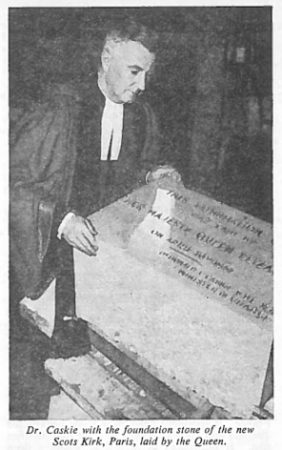

The Paris congregation of the Scots Kirk was established in 1858 with services held in the Temple Protestant de l’Oratoire du Louvre (145, rue Saint-Honoré). In 1883, the congregation purchased the former American Episcopal church building at 17, rue Bayard and by 1885, the building was ready for Sunday services. Prominent people such as President Woodrow Wilson, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, and Eric Liddell (“Chariots of Fire”) worshiped at the Rue Bayard church. During the German occupation, the church was shut between June 1940 and August 1944 but reopened after liberation.

There have been three buildings on this site. The original building stood until the late 1950s when it had to be demolished due to structural damage from World War II. Queen Elizabeth II laid the foundation stone for the new church on 10 April 1957. Unfortunately, the new construction did not hold up over time and by the 1980s, it was determined that major structural faults rendered the building unsafe, and a new building would once again be needed. A deal was negotiated with a developer to allow them to build private apartments in return for demolition and construction of a shell for the “new” church.

Donald Caskie wrote his book, The Tartan Pimpernel, about the time the decision was made to rebuild after the war. All proceeds from the sale of the book went into the construction fund for the second building. Groundbreaking for the third building took place in 1999 and construction was completed in 2002. It was a considerable financial burden for the congregation, but all loans were repaid in full by 2014. Today, proceeds from the sale of Rev. Caskie’s book goes to a fund that helps the church to carry on their work in the City of Light. Information for donating can be found at the end of the recommended reading section.

Today, the Scots Kirk Paris is home to a permanent Donald Caskie exhibit. Photographs, personal items, and documents during his time in Paris can be viewed. Some of these include Rev. Caskie’s Gaelic bible and the key to the “old” Scots Kirk that he gave to M. Gaston, owner of the next-door café after the church was locked up on 9 June 1940. Rev. Caskie’s nephew, Tim Caskie, was kind enough to donate many of the exhibit’s items including the bible.

Journey to Marseille

It was only a matter of days before the German Wehrmacht would march into the open city of Paris. Two million Parisians packed up what they could and fled the city. They left in cars, on bikes, and by foot. Joining up with six million other French citizens trying to stay a step ahead of the invading army, the “Exodus” was excruciatingly slow. As people headed south and west, Luftwaffe fighter planes were responsible for hundreds of deaths as they strafed the fleeing men, women, and children along the roadside.

Rev. Caskie personally closed the church on 9 June 1940 and handed the door key to M. Gaston. Walking, cycling, and catching automobile rides, Rev. Caskie finally made his way to Bayonne, a seaport on the south-west coast. The British consulate offered him a place on the last ship leaving France. Rev. Caskie refused to accept the offer since God had placed him in France to minister.

The Battle of Dunkirk took place between 26 May and 4 June 1940. The Germans had trapped British and other Allied troops along the coast of France with only two options: surrender or flee into the sea. The evacuation of Dunkirk involved about 861 vessels rescuing 338,226 men off the beach. Unfortunately, 140,000 soldiers were not able to escape, and they were stranded in German-occupied France either as prisoners or left to their own to get back to England. Some of these men became the first customers of the original escape lines run by résistants and MI9, the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) department responsible for originating and administering escape (and later evasion) lines.

Rev. Caskie was told that many of the men who had eluded capture were heading for Marseille, a major French seaport city on the south coast. Hearing that, he left for Marseille with the calling to serve and minister to the soldiers.

The British Seamen’s Mission

After arriving in Marseille with visits to the British and American consulates, Rev. Caskie stopped at the local police station where he was once again offered the opportunity to leave France. Refusing, Rev. Caskie announced his mission was to help his fellow citizens in their hour of need. The police already knew their orders from the Gestapo, and they warned the reverend that he could find accommodations and assist British citizens but if he gave help to British soldiers, arrest and internment would be his reward. On the way out of the police station, an official quietly suggested the padre take over the British Seamen’s Mission at 46, rue de Forbin. The police officer once again warned Rev. Caskie not to be caught harboring British soldiers but added one more warning: “And trust no man, m’sieur. You will be watched. I know it. You must beware of paid agents, and of sudden raids.” A warning that Rev. Caskie would soon find prophetic.

Located near the harbor in a rough and tumble area known as Le Vieux Port (“the old harbor district”), the Seamen’s Mission was deserted when Rev. Caskie arrived. Three sailors were standing outside, and he quickly recruited them to assist with cleaning up the mission. A sign was nailed to the front door making it clear the mission was open only to British civilians and seamen.

There were thousands of disheveled British soldiers hanging around the seafront. Many were wounded. Most were exhausted. All had no place to go. Their fate would inevitably be arrest by the pro-Nazi French/Vichy police (under German orders). Rev. Caskie saw these men as his flock, and he was determined to minister to them. He also made the decision it was his responsibility to aid in their escape.

Soon the mission was crowded with soldiers. Civilian clothes replaced their uniforms which the reverend dumped into the harbor. Food was difficult to come by for that many mouths, but Rev. Caskie seemed to always make it work. He began to build a network of people who clandestinely supported his efforts at the mission. Throughout the summer of 1940, Rev. Caskie ministered to his ever-growing flock. His mission quickly came to the attention of MI9.

Morning Raids

The Gestapo and Marseille police knew about the activities inside the Seamen’s Mission, but they could not prove it. The mission was raided on a regular basis. Almost every day, the police showed up around 6:00 AM but they never found anything to implicate Rev. Caskie or his resistance activities. One morning, Vichy detectives knocked on the door earlier than normal. The head detective was rather rude and to the point with Rev. Caskie. He accused the reverend of running the mission to house, harbor, and aid British soldiers with escape to Spain. For hours, the detectives searched the building but never found any incriminating evidence. As the head detective stood in the door to leave, he turned to Rev. Caskie and said, “This is not good-bye, Monsieur Pasteur but just au revoir.”

The Pat O’Leary Escape Line

On a late evening, Rev. Caskie was working at his desk when he sensed the presence of another person in the room. Raising his head, Rev. Caskie was confronted by a tall man in his mid-twenties with a fair complexation standing in front of him. Introducing himself as “Major X” and a British intelligence officer, the stranger was there to request that Rev. Caskie gather intelligence information from the soldiers who came through the mission. Rev. Caskie agreed and as quickly as he arrived, Major X left the room. Rev. Caskie began to accumulate intelligence information and recorded it in his “Book of Words.” He wrote the information in Gaelic and relayed the information back to London.

Ian Garrow (1908−1976) was a British officer with the Glasgow Highland Light Infantry and Seaforth Highlanders when he and others were trapped in the chaos of the Dunkirk evacuation. He made it to Marseille in August 1940 where he founded the Pat O’Leary escape line. Capt. Garrow met with key individuals (e.g., Nancy Wake, Tom Kenney, and Elisabeth Haden-Guest) to help him set up the line but he was missing something. He needed the final link that could arrange for a successful journey over the Pyrenees mountains and into Spain. This brought him to see Rev. Caskie at 3:00 AM in the mission and by October 1940, the new escape line was up and running. (Click here to read the blog, Escape Lines.)

Maj. Gen. Count Albert-Marie Edmond Guérisse (1911−1989) was a Belgian resistance member who joined the British Royal Navy as Lieutenant Commander Patrick Albert O’Leary. In April 1941 while working undercover for British-led Special Operations Executive (SOE), Guérisse was arrested in southern France. He escaped two months later and went to Marseille where he met Garrow who convinced him to join the escape line. From that time on, it became known as the “Pat O’Leary Line.” With approval from SOE, Guérisse joined the escape line and quickly proved his abilities to successfully move men through France, over the Pyrenees, and into Spain.

Garrow was arrested in October 1941 but managed to escape in late 1942 and with the help of the Pat line, returned to England where he remained through the end of the war. Pat O’Leary took over as leader of the escape line. However, the Pat line was infiltrated in January 1943 by the French traitor, Roger le Neveu. Two months later, O’Leary was arrested by the Gestapo and spent the remainder of the war in concentration camps. As a Nacht und Nebel (NN) prisoner and sentenced to death at KZ Dachau, it was a miracle Guérisse/O’Leary survived. (Click here to read the blog, Night and Fog.)

The Pat O’Leary escape line was a well-oiled machine and Airey Neave later estimated at least six hundred men successfully made it back to England due to the efforts of the escape line. Rev. Caskie’s activities were an integral part the line’s success. However, his involvement with the Pat Line ended abruptly in April 1941. His premonition about Paul Cole was correct. Cole had infiltrated and betrayed the resistance organization. Hundreds of arrests were made including Rev. Caskie. Despite the infiltrations and betrayals of le Neveu and Cole, the escape line managed to survive and continued to assist escapees and evaders.

Grenoble

Put on trial, Rev. Caskie was found guilty and sentenced to two-years imprisonment, but the court suspended the sentence and gave him probation on the condition he leave Marseille (it was “suggested” he go to Grenoble), close the mission within ten days, and never engage in resistance activities again. Once more, British intelligence offered Rev. Caskie a plane ride to England and once again, he refused. His next stop would be Grenoble.

Rev. Caskie spent nearly two years in Grenoble where he caught up with old friends and acquaintances from the University of Edinburgh. His home was the Hôtel de l’Europe whose owner was pro-Nazi and Rev. Caskie assumed any unusual activities were reported immediately to the local Gestapo by the owner. One of the reverend’s activities was being chaplain to prisoners. Rev. Caskie saw to it that he carried “tools of escape” on his visits, and he began to resurrect his resistance activities. The Germans knew what he was up to but like Marseille, they never could get any evidence to incriminate the pastor. The Gestapo moved into the Hôtel de l’Europe and every move Rev. Caskie made was known to the Nazis.

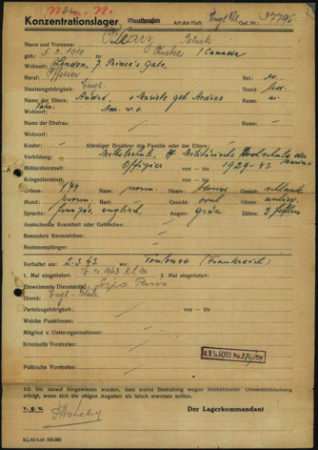

Arrest, Trial and Death Sentence

Eventually, Rev. Caskie was kicked out of the hotel, and he found a room at a local boarding house. On 16 April 1943, he was arrested and thrown into the Caserne Hoche (Hoche Barracks) where he stayed for several weeks before being transferred to a prison in Cuneo, Italy. Then it was on to Nice and the beautiful Villa Lynwood that served the Gestapo and their accomplices, the Milice (a Vichy paramilitary organization) as a place of torture and murder. The next move was to a medieval Italian fortress where prisoners were left to rot and in July 1943, Rev. Caskie was taken in chains back to Marseille where his new residence was the Saint-Pierre Prison. The last journey by train was to Paris and the infamous Fresnes Prison. It was the Gestapo prison where prisoners faced either death within its walls or a postponement of death via deportation.

On 26 November 1943, Rev. Caskie was taken to Gestapo headquarters on rue des Saussaies for his trial. There were twelve judges: ten men and two women. The proceedings lasted the entire day and into the early evening. He was accused of being a spy, an agitator, and an agent aiding with the escape of soldiers and POWs. One more crime was leveled at Rev. Caskie: being a friend to Jews. Witnesses were called and the most damaging one was Pierre, one of the guides used by the mission for the trek over the Pyrenees. The verdict was not hard to predict: guilty with a sentence of death.

Waiting to Die

For seven weeks, Rev. Caskie was held in his Fresnes cell expecting death each and every day. Soon after the trial, Rev. Caskie asked to see a pastor. A German Lutheran minister, Hans-Helmut Peters (1908−1987) soon arrived. In addition to God and faith, the two ministers found they had other things in common. Peters told his new friend that he would do everything possible to see that the death sentence was revoked.

While on leave, Peters visited Berlin to try and get the Nazis to stay the execution orders. He was successful and on 7 January 1944, Rev. Caskie learned his death sentence had been cancelled. He was interned north of Paris at Caserne Saint-Denis where life became more pleasant and civilized for the prisoners and he was allowed to conduct services in the chapel on the top floor of the building. On 6 June 1944, the prisoners were informed of the Allied invasion on the Normandy beaches and a special service was held. Two months later, Rev. Caskie was lying in bed one morning and heard the guns. The German occupiers and Pastor Peters had left Paris. Liberation took place when Gen. Leclerc’s tanks entered the city on 25 August and the remaining German garrison surrendered.

After Liberation

After Rev. Caskie returned to England in late 1944 for a short visit, he ran into men who came through the Seamen’s Mission and successfully made it back to the U.K. At times, he came into contact with the families of the men he helped, and the gratitude was limitless.

Times were tough in Paris after the liberation in August 1944. Winter was approaching and food was still scarce as well as the fuel needed to heat apartments. Rev. Caskie was concerned about the welfare of his congregation at Scots Kirk, and he was advised to see a certain major at the British embassy. Presenting himself at the embassy, Rev. Caskie was told the major was too busy to see him. However, after the major received Rev. Caskie’s card, he quickly appeared in the hallway. The officer introduced himself as “Major X” and he agreed to assist Rev. Caskie in any manner. The first request was coal to heat the church. Through the efforts of the former Major X, Scots Kirk was well stocked with food, coal, and other necessities to ensure the church and its congregation would not suffer through the winter.

On the first Sunday after liberation, Rev. Caskie gave the sermon at Scots Kirk Paris. After the service, he walked outside to see a soldier sitting in the turret of a passing tank. It was a man who passed through the Seamen’s Mission three years earlier.

Rev. Caskie returned to Scots Kirk Paris after the war ended and stayed until 1961 when he finally headed home to Scotland. He became the minister of Old Gourock Church and later, the Wemys Bay and Skelmorlie parish church in Ayrshire overlooking the Firth of Clyde. By the 1970s, Rev. Caskie was suffering from ill health and eventually moved in with one of his brothers in Greenock.

Rev. Dr. Donald Caskie passed away on 27 December 1983 and is buried with his parents in Bowmore, Islay in the New Parish Churchyard of Kilarrow Church (“The Round Church”).

This Is Your Life

On 7 September 1959, Rev. Caskie was honored by the BBC as the subject of This is Your Life (Edition no 100, Subject no 100). One of the invited guests was Rev. Hans-Helmut Peters.

Next Blog: “New Forest Airfields”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

BBC. Church war hero “the Tartan Pimpernel” honoured in France. 28 October 2019. Click here to read the article.

Caskie, Donald. The Tartan Pimpernel. Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited, 1996. Originally published by Oldbourne (London) in 1957.

Church of Scotland: “Hero minister who helped airmen escape prison honoured”. Click here to read the article.

Fitzsimons, Peter. Nancy Wake: A Biography of Our Greatest War Heroine 1912−2011. Sydney, Australia: HarperCollinsPublishers, 2011. First Edition (2001).

Foot, M.R.D. SOE in France. London: Whitehall History Publishing (Frank Cass Publishers), 2004. Original Edition (HMSO, 1966).

Foot, M.R.D. and J.M. Langley. MI9: Escape and Evasion 1939−1945. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1980.

Ireland, Josh. The Traitors: A True Story of Blood, Betrayal and Deceit. London: John Murray Publishing, 2017.

Jeffery, Keith. MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909−1949. London: Bloomsbury, 2010. Page 410.

MacPherson, Hamish. Scotland Back in the Day: Reverend Donald Caskie, the kirk minister with a double life as a war hero. The National. 31 July 2017. Click here to read the article.

Murphy, Brendan. Turncoat: The Strange Case of British Sergeant Harold Cole, the Worst Traitor of the War. San Diego: Harcourt, First Edition (1987).

Neave, Airey. The Escape Room. New York: Kensington Publishers, First Edition (1980).

Neave, Airey. Saturday at M.I.9: The Classic Account of the World War Two Allied Escape Organization. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Military, 2004.

The PAT Line (Pat O’Leary line). Click here to read the article.

Tremain, David. Agent Provocateur for Hitler or Churchill? The Mysterious Life of Stella Lonsdale. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword History, 2021.

WW2 Escape Lines Memorial Society. Click here to visit the web-site.

Dr. Caskie wrote his book for the purpose of providing funds to repair the war-damaged building in Paris. Subsequent editions provide money to the church for on-going operations.

If you would like to donate to the Scots Kirk Paris on behalf of the memory of Rev. Donald Caskie, here is the information:

Isabel Hardman

Appeal Committee Chairman

B.P. 242 ÉTOILE

75770 PARIS CEDEX 16 – FRANCE

Please make checks payable to: Scots Kirk Paris Development Fund

I’d like to thank Scots Kirk Paris and the Church of Scotland’s Life and Work for their kind permission to use certain images of Dr. Caskie.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I just returned from our trip to Rome and a cruise through the Suez Canal, down the Red Sea, and ending at Dubai. I have so much to share with you including observations and recommendations from the trip. So, today I will highlight some of our experiences while saving the recommendations for our next blog (New Forest Airfields; 2 December 2023).

It was our first visit to Rome and the “City of Love” did not disappoint us one bit. One of the initial “take-aways” was our amazement at the narrow streets throughout the city. Second, I don’t think we’ve ever tasted pasta as good as we had in Rome (don’t tell my doctor). Sandy got her fill of gelato but please don’t tell her doctor. We had a wonderful private guide for three days and covered a lot of territory (more on that in the next blog). Our purpose in taking this particular cruise was to go down the Suez Canal. (Once you’ve been through the Panama Canal, you must do the Suez.) While a priority excursion for many of us to Petra, Jordan was cancelled, the day we spent traversing the canal was quite an experience. (Here’s a tip: you will want to book a starboard (right) cabin going south or a port (left) cabin if sailing north on the canal.)

The ship was scheduled to enter the canal at 3:00 AM but we were delayed five hours. (We didn’t complain because it was daylight when we started down the canal at eight in the morning.) What we didn’t know at the time was that the United States Strike Force led by the USS Eisenhower “cut in line” in front of us. We followed the Eisenhower carrier all the way to Suez and the end of the canal. One of the passengers made the comment to me that she was worried being this close to these naval ships. I said to her, “Lady, we are probably in the safest position we could be right now in this part of the world.” I have attached an image of the USS Eisenhower and you can see our cruise ship following the carrier to the right. We found out later that shortly after we started down the canal, a U.S. nuclear attack submarine entered behind us.

Another sea adventure was watching the six pirate boats pass by the ship after coming out of the Red Sea. At that point, we were sandwiched between Yemen and Somalia. It was explained to us that pirates consider cargo ships easier targets than cruise ships. Besides, I know cruise ships are heavily armed. (I didn’t get the chance to tell that to the lady passenger.)

We stopped at Muscat, Oman (our consolation prize for missing Petra) and let me tell you, I don’t think we have ever been in a more beautiful city. The capital of Oman was spotless. There wasn’t a speck of dust or trash anywhere. We thought Singapore was the cleanest city we’d ever been in but no, Muscat was cleaner. The architecture is Moorish, and the buildings are built at a low elevation and painted bright white. There was no graffiti anywhere. Dubai was very similar, but its architecture was more modern and very unique.

In our next blog, I will introduce you to the hotel we stayed at, some of the restaurants where we ate, and our tour guide, Marisa. Hopefully, we can add some value for your next trip to Rome.

Until then, arrivederchi.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting on Our Blogs

We heard from our good friend Roland K. about two months ago. Roland lives in Glasgow, Scotland and was wondering if I had ever visited the Church of Scotland in Paris ⏤ I didn’t even know the church had a presence in the city. He told me about Donald Caskie, and I said that I would do some research as it sounded like the story had the potential for a good blog topic. If I had only known! Thank you, Roland, for sending me down a very interesting rabbit hole.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Shepherd.com is like wandering the aisles of your favorite bookstore.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Check out Stew’s new bookshelf on the French Revolution.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross

Wow! Another great story of amazing courage and survival against the odds. Thanks.

Hi Greg, as always, we appreciate your feedback. STEW

Hi. Read your blog post about the escape lines with great interest. My great-uncle was a tech sergeant on a B17 and was shot down, then sheltered by many brave citizens in Brittany. He was one of the five American aviators taken to the Paris train station with Roger Leneveu and captured due to his betrayal. It was the beginning of the end of the Pat Line. My great-uncle spent two years in a stalag until he was liberated at the end of the war. Thanks for helping keep these stories alive.

Hi Carol, Thanks very much for your nice comments. I hope your great-uncle left you and the family with many stories of his experiences during the war. STEW