One of the more effective resistance efforts during World War II was the establishment and operation of multiple escape lines in occupied countries such as France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Risk/reward theory certainly applies to these efforts as the escape lines were probably some of the most dangerous operations performed by resistance fighters and the people assisting them (“helpers”). The greatest threat to the ongoing operation of the lines was not the Nazi security forces (e.g., Sichersdienst and Gestapo). It was the infiltration and betrayals by French, Belgian, and Dutch traitors. After the war ended, many of those who betrayed their comrades (and countries) were caught, tried, and executed. Unfortunately, some were never brought to justice.

Did You Know?

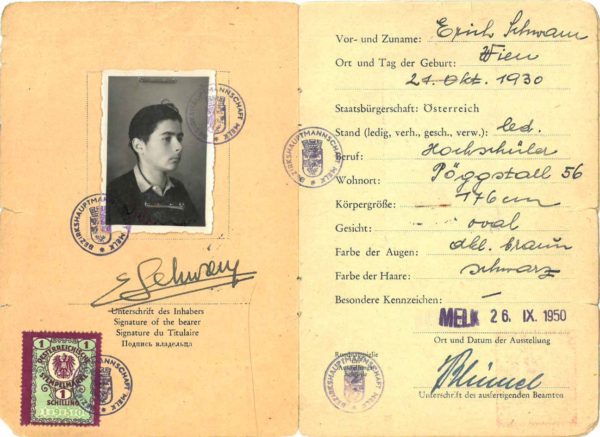

Did you know that the small village of Chambon-sur-Lignon in south-central France recently inherited 2.0 million euros? Erich Schwam (1930−2020) had no heirs when he passed away this past December. Why did he pick this small remote hamlet in a wooded area to leave more than US $2.4 million? As an Austrian child, the residents of Chambon-sur-Lignon sheltered Erich and his Jewish parents during the Nazi occupation of France. Besides Erich and his family, the village saved the lives of almost five thousand Jews (thirty percent were children). It was through the leadership of the two Huguenot (Protestant) pastors, André Trocmé and Édouard Theis along with Roger Darcissac (head of education for the village) that the villagers banded together, at great personal risk, to devise a system to keep everyone out of the hands of the Nazis. The Jews would disappear into the woods when Nazi patrols came searching for them. The all-clear signal was when people from the village went out into the forest and began singing. Trocmé, Theis, and Darcissac were arrested by the French police and interned at Saint-Paul-d’Eyjeaux. They were released months later and returned to Chambon-sur-Lignon where they continued their resistance activities.

Yad Vashem named Pastor Trocmé as Righteous Among the Nations in 1971 followed by Pastor Theis in 1981 and M. Darcissac in 1988. Chambon-sur-Lignon is only the second city collectively honored as Righteous Among the Nations (the Dutch village of Nieuwlands is the other). Click here to watch the video clip Le Chambon: How a Jewish Refugee Became a Freedom Fighter in WWII.

By early 1943, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) had arrived in England to establish bases for its long-range bombers: B-17s and B-24s. For more than three years, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) had been bombing the continent during nightly runs. Now it was time for the Americans to begin their campaign of daylight bombing. This meant more planes were going to be shot down and an increasing number of crews would likely parachute and land behind enemy lines (i.e., occupied countries). There needed to be a way to get these downed Allied airmen back to England safely.

Escape Lines

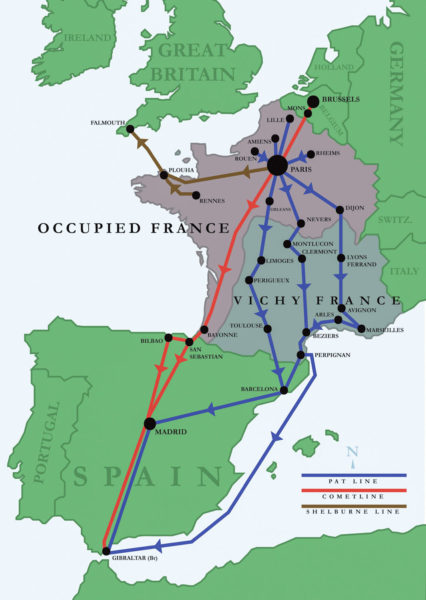

Escape lines throughout the occupied countries (primarily France, Belgium, and the Netherlands) were established to guide the downed airmen (“evaders”) and escaped POWs (“escapees”) back to London. These were set-up either independently or by Allied intelligence services such as MI9 (British Directorate of Military Intelligence Section 9). Regardless of where the line originated, the majority of them ran through France with the goal of getting the men over the Pyrenees mountains, into “neutral” Spain, and then to Gibraltar for the plane ride to England. Thousands of men and women risked their lives saving the downed airmen and escaped POWs⏤ unfortunately, many of these résistants were caught and executed by the Nazis or did not survive the concentration camps.

The earliest escape lines (e.g., the predecessor to the Pat O’Leary line) were inaugurated after the Battle of Dunkirk and the subsequent evacuation of about 338,226 men between 27 May and 4 June 1940. Unfortunately, not all Allied troops were able to be evacuated and they were either captured by the Germans or went into hiding. Many of the evaders were sheltered and fed by locals. The first escape lines were created by Breton fishermen who ferried their passengers across the English Channel (all the while dodging German U-boats).

There were many escape lines established during the war and it is estimated that more than five thousand evaders and escapees successfully made it back to London with the assistance of helpers. Most of these “underground railroads” took the evaders to London via Spain but some had final destinations in Swizerland and Sweden. The lines could become very complex with hundreds of helpers working for a particular escape line. It was not uncommon for a downed airman to be shuttled between different escape lines on their way to Spain. The one common factor all of the organizations shared was the high probability of being denounced or infiltrated by traitors working for the German security forces (e.g., the Gestapo or Sicherheitsdienst).

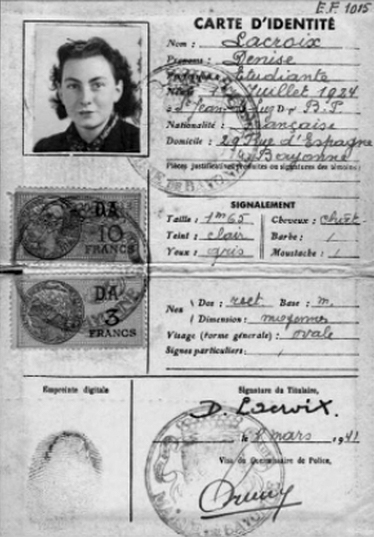

If the airman was fortunate to survive by parachuting out of his crippled plane, there was a good chance he would be sheltered by local citizens, many of them were farmers (at great risk to their lives and the lives of their families). He would be taken into the village, fed and given civilian clothes along with false papers. Then instructions were given to him to meet up with someone and obtain transportation to Paris. It seems that regardless where airmen landed, they were all taken to Paris to start their journey back to freedom. In Paris, they were sheltered in a safe house and put in contact with an escape line helper. Once it was determined to be relatively safe by their handlers, the men were usually put on a train headed south toward the border of Spain and another safe house. Once there, a guide would take them by foot up and over the Pyrenees mountains and into Spain. Despite being officially neutral, Spain was anything but neutral and the men had to be careful to avoid the Spanish police. Once they made it to the British consulate, arrangements would be made to take them to Gibraltar for the flight back to England. Unfortunately, everything did not always go as planned.

Pat O’Leary Line

One of the earliest escape lines was the Pat O’Leary line (PAO). Established in October 1940 by Ian Garrow (1908−1976), the line was taken over by Albert-Marie Guérisse (nom de guerre: Pat O’Leary) one year later after Garrow was arrested by the Nazis. Guérisse (1911−1989), a Belgian army doctor, was trained by British Naval Intelligence and captured by the Vichy coast guard while on a mission in southern France. Guérisse escaped and made his way to Marseilles where he joined Garrow’s escape organization. In his first four months, Guérisse was responsible for assisting in the escape of fifty men from the prison of St. Hippolyte du Fort and guiding them to safety over the Pyrenees and on to England. In December 1942, Guérisse and others (including Nancy Wake; click here to read the blog The White Mouse) successfully planned and executed Garrow’s escape from prison. Garrow subsequently returned to London in February 1943 where he remained for the rest of the war.

The period of greatest activity for the PAO was between the summer of 1942 and early 1943. Downed Allied airmen were fed, clothed, given identity cards, and hidden until it was time for them to leave. All of the evaders were taken to Marseille before their trip over the Pyrenees and into Spain. By the end of the war, the PAO was responsible for more than six hundred Allied personnel (primarily downed airmen) escaping from occupied France, Netherlands, and Belgium.

The escape line and its nearly one hundred workers were betrayed at least twice during its existence. In late 1941, a PAO courier, Harold Cole (1906−1946) a.k.a. Paul, was accused of embezzling money from the escape line and Guérisse had him locked up. Just before Guérisse gave the order to have him executed, Cole escaped and turned himself into the Abwehr (German military intelligence). He handed over to the Nazis a thirty-page list of PAO résistants and their addresses. Working from Gestapo headquarters in Paris at 84, avenue Foch, Cole was responsible for the decimation of PAO’s existence in northern France. During the winter of 1942, a PAO member and double agent, Roger le Neveu (a.k.a. Roger le Legionnaire), infiltrated the escape network. In March 1943, Guérisse was arrested based on information Neveu provided the Nazis. At that point, the PAO became nearly extinct but Marie-Louise Dissard (nom de guerre: Françoise) took over what remained of the escape line and ran it until the end of the war (the network became known as the Françoise line).

After the war, Cole was betrayed by his ex-girlfriend and arrested. Ultimately, he was shot to death by French police after trying to resist arrest. Neveu was summarily executed by the French maquis. Guérisse was interrogated and tortured by the Gestapo but never revealed any information. He was sent to a series of concentration camps, including KZ Mauthausen and KZ Dachau where incredibly, he survived the war.

The Comet Line

Réseau Comète, or the Comet network was an escape line that originated in Belgium in the spring of 1941 under the leadership of 24-year-old Andrée de Jongh (1916−2007), Arnold Deppé (1907-?), and Deppé’s cousin, Henri de Bliqui. The day after the three of them met in April 1941 to discuss the network’s organization, Henri de Bliqui was arrested (and later executed in Berlin). Arnold Deppé was arrested in August 1941 and deported to Germany where he managed to survive incarceration in various concentration camps. This left Andrée de Jongh (nom de guerre: Dédée) to run the escape line along with her father, Frédéric de Jongh (1897−1944). Click here to watch a video clip on Andrée de Jongh.

Comet was in existence between 1941 and 1944. It was one of the largest and most efficient escape lines in occupied Europe. It is estimated that about three thousand civilians (of whom 70% were women) were active in the line. During its existence, Comet helped 776 people evade the Nazis and successfully return to England. Like many of the other escape lines, Comet was financed by MI9.

Before his arrest, Deppé recruited Elvire de Greef (nom de guerre: Tante Go) and her family (including her 16-year-old daughter, Janine) to assist in sheltering the evaders prior to the journey over the Pyrenees. The de Greefs lived in Anglet near the Spanish border and were able to help get the men over the mountains. Tante Go ran the southern portion of the Comet line and, next to Dédée, is considered to be the most important member of the network. The first infiltration of the Comet line occurred in August 1941 when Victor Demets, a Belgian working for the Gestapo, betrayed Deppé while he was guiding six men. At about the same time, Dédée made it to Spain where she met and eventually persuaded the British to finance the escape line. However, she insisted on remaining completely independent of British control (including accepting MI9 agents for field work).

After Deppé’s arrest, Dédée felt that staying in Belgium was unsafe and she moved to Paris. She left her father in charge of the Belgium portion of the line. His job was to shelter the downed airmen and provide them with food, clothing, and documentation prior to sending them on to Paris where Dédée and her team would send them to Tante Go and her helpers for the next stage of their journey. Andrée de Jongh made twenty-four successful roundtrips over the mountains while escorting 118 evaders to safety. She was aided by several Basque guides (most were smugglers), but her favorite was Florentino Goikoetxea. By April 1942, it became too dangerous for Frédéric de Jongh to remain in Belgium, and he moved to Paris where he took charge of the Paris hub. Jean Greindl (nom de guerre: Nemo) took over leadership of the Belgium segment.

On 15 January 1943, Dédée was arrested in a safe house along with three evaders and Frantxia Usandizanga, the owner of the safe house. They were betrayed by a Basque guide whom Dédée did not trust. Under intense interrogation, the Gestapo didn’t believe her when she admitted to being the leader of the escape line (the Germans did not comprehend that a young woman could lead such an organization). Later, while imprisoned in KZ Ravensbrück, Dédée’s role was discovered by the Nazis. However, when they came to get her, Dédée evaded them by hiding her identity. After de Jongh’s arrest, the escape line was led by various individuals. In June 1943, the line almost collapsed as a result of the infiltration of a traitor who tipped off the Gestapo.

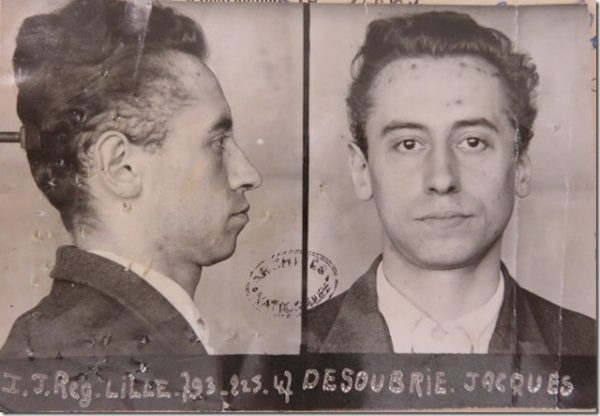

The Comet line was betrayed many times. The first was in November 1942 when the Belgium hub was compromised, and more than one hundred people were arrested. The next time was the betrayal of Dédée by the disgruntled guide. The most devastating infiltration was perpetrated by the Belgian turned Gestapo infiltrator, Jacques Désoubrie (1922−1949) in mid-1943 (click here to read the blog The Last Train Out of Paris). The greatest number of Comet résistants (more than 250) were arrested as a result of Désoubrie’s treachery.

While the many infiltrations brought the Comet line to its knees, each time it managed to be resurrected by a new leadership team (“next man up”). However, by the spring 1944, the leaders of the Comet line and MI9 agreed to cease their activities in guiding the men to Spain and eventual return to London. (By this time, only three of the dozens of Comet leaders were still alive and not in prison or a concentration camp.) By then, it was obvious that an Allied invasion was imminent, and the strategy shifted to hiding the evaders in forest camps to wait for liberation by the Allied armies.

Andrée de Jongh survived Fresnes prison, KZ Mauthausen, and KZ Ravensbrück. After the war and obtaining her nursing credentials, Andrée went on to work in the African colonies tending to leprosy patients. She was awarded the United States Medal of Freedom, the British George Medal, and honored by the French with the Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur. Her father, Frédéric de Jongh, was arrested in June 1943 and executed by the Nazis in March 1944.

Tante Go and her family survived the war⏤none of the family were captured or killed. Elvire de Greef was awarded the George Medal among other honors. Janine de Greef was awarded medals by the Americans, French, British, and Belgians. The Basque guide, Florentino Goikoetxea, was arrested by the Germans but escaped with the aid of the de Greef family. Nemo was arrested in 1943 and killed while in prison. Frantxia Usandizanga was beaten to death in the concentration camp. The traitor, Désoubrie, was tried, convicted, and executed by the French after the war.

The Shelburne Line

The Shelburne escape line was the successor to an ill-fated escape line known as Oaktree. Although many of the escape lines were financed by MI9, they were founded, organized, and run by citizens of the occupied countries. The Oaktree and Shelburne lines were created by Airey Neave (1916−1979), a British intelligence agent with MI9. (Another major escape line, Bourgogne, was established by the Free French intelligence service from London.)

By late 1943, many of the major escape lines (e.g., Comet and Pat O’Leary) had been infiltrated and either weakened or decimated. At the same time, the Americans and British were expanding their bombing campaigns and a greater number of airmen were finding themselves on the ground evading capture by the Germans. The Oaktree line was managed by MI9 and it differed from many of the other escape lines in that it guided Allied evaders to London by boat rather than via Spain, Gibraltar, and a plane ride. Oaktree’s agents were warned not to contact the Pat O’Leary line as it had been compromised by the Nazis. Unfortunately, its leader, Vladamir Bouryschkine (he had previously worked for PAO), did not heed those instructions and Oaktree was betrayed by Roger le Neveu. Oaktree’s wireless operator, Raymond Labrosse (c.1922−1988), made it back to London where he persuaded Neave that an escape line was still feasible. Neave resurrected Oaktree but gave it the name “Shelburne.” He placed Lucien Dumais (1904−1993) in charge and sent Dumais and Labrosse back to France in November 1943.

As an aside to our story, one of my prior blogs talked about a B-17 that was shot down (click here to read the blog Rendezvous with the Gestapo) in March 1943. Two of the downed crew and now evaders, Lt. Frank Perrica and Sgt. Salvadore Tafoya were initially handled by several of Oaktree’s survivors including Labrosse before being turned over to the Bourgogne line.

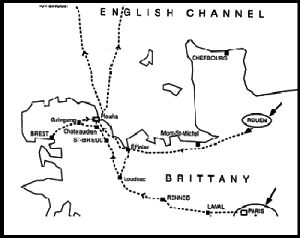

Prior to D-Day, evaders on the Shelburne line were taken to the seaside town of Plouha in Brittany (to the west of the Normandy beaches). The Bonaparte beach was their departure point where Royal Navy motor gunboats picked up the evaders for the voyage across the channel to Plymouth, England. This was very risky since the Germans had fortified the coastline in anticipation of an Allied invasion. After the 6 June 1944 invasion, Shelburne continued until August 1944 when it conducted its last evacuation.

Shelburne successfully assisted 307 evaders. Unlike Comet and Pat O’Leary, none of the Shelburne line members were captured or killed. Labrosse attributed their success to not making the same mistakes as their fellow resistance fighters in Comet or PAO.

The Routes

The Pat O’Leary line used two routes. The first ran from Paris to Toulouse via Limoges and then over the Pyrenees to Barcelona. The second route started in Paris and went through Dijon, Lyons, Avignon to Marseille. Then it was on to Nîmes, Perpignan, the Pyrenees, and Barcelona. The last stop before London was Gibraltar.

The Comet line was Brussels to Paris and then on to Tours, Bordeaux, Bayonne, the Pyrenees, and then to San Sebastián in Spain. From there, the evaders went to Bilbao or Madrid before arriving in Gibraltar.

The Shelburne line also started in Paris. However, it sent its evaders west to the Brittany coast and across the English Channel via boat.

Aftermath

These are only three escape lines out of hundreds of formal and informal resistance networks that specialized in getting evaders and escapees back to freedom. The official post-war history of MI9 recognizes that more than five thousand people made it back to either London or Switzerland via the escape lines with the assistance of more than 100,000 helpers.

★ Learn More About the Escape Lines ★

Atwood, Kathryn. Women Heroes of World War II. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2011.

Eisner, Peter. The Freedom Line. New York: Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2004.

Hannah, Kristin. The Nightingale. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015. Hemingway-Douglass, Réanne. The Shelburne Escape Line. Washington: Cave Art Press, 2014.

Janes, Keith. They Came from Burgundy: A Study of the Bourgogne Escape Line. Leicestershire: Matador, an imprint of Troubador Publishing, Ltd., 2017.

Katsaros, John. Code Burgundy: The Long Escape. Norwalk, CT: Oakford Media, 2009.

Murphy, Brendan. Turncoat: The Strange Case of British Sergeant Harold Cole, the Worst Traitor of the War. San Diego: Harcourt, 1987.

Rossiter, Margaret L. Women in the Resistance. New York: Praeger Publishers, a Division of CBS, Inc., 1986.

Kristin Hannah’s book, The Nightingale, is fiction but it is very loosely based on Andrée de Jongh and the Comet line. This is a book that once you pick it up and begin reading, you will not put it down until you finish the book. I guarantee it.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

We are now one year into COVID-19. It was about this time last year that people began to take the pandemic seriously, including our politicians. We began to experience lockdowns, wearing masks, and stopped eating out and traveling. Toilet paper, cleaning supplies, and other essential products became non-existent. State legislators gave their governors special powers⏤almost to the point of a governor becoming authoritarian. In Michigan, the governor banned the sale of garden tools and paint. You were not allowed to go out in a boat. Restaurants and bars were closed down in almost every state. I could go on and on, but all of you lived through it.

Fortunately, we are at the point where we can see the light at the end of the tunnel. Slowly but surely, we all have or will have the opportunity to get vaccinated. States seem to be opening up (our state, Florida, is completely open) and our government officials are finally seeing (and demanding) that our children must return to the classroom. People are tired of state-controlled authoritarian edicts and what seem to be two sets of rules⏤one for the politicians and one for the rest of us⏤and our citizens are beginning to do something about it (e.g., the California governor recall efforts).

Needless to say, this has been a trying time for everyone. No one escaped being affected. Some of our publishing team suffered the loss of loved ones and our hearts go out to them.

Sandy and I are “retired,” so our days are pretty much the same: working on the books, blogs, and lectures. In fact, the past year for us has been like the movie, Groundhog Day with Bill Murray.

So, for our many friends outside the United States, hang in there. As we say in America, “The calvary is on the way.”

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Phyllis C. for contacting us regarding our recent blog, Kindertransport and Mr. Winton (click here to read the blog). She mentions that the story is an “uplifting” story. I agree and it’s too bad there aren’t more like it.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2021 Stew Ross

Hi Stew,

Interesting blog – thank you. Fascinating gems of information.

Hi Pat, Thanks for your comment. I’m waiting for Paul M. to contact me and let me know I messed up on something since he’s the expert on WW2 escape lines. Ha ha. STEW

Hi Stew,

Really well researched article. Trying to find out what route did the Béthune group in late 1940 use to Brittany and when it joined up with the Musée de L’Homme group did it use the Pat O Leary Line? Réne Sénéchal brought many packages south and I’d love to know the routes.

Regards,

Cathi Fleming

Hi Cathi; Thanks for your kind comments. Unfortunately, I’m not aware of the Béthune group. I tried doing some research but came up empty. I sent you a separate e-mail with some links to escape line memorial organizations. I also included the contact information for Fred. G., the son of the founder of the Possum escape line. I believe he is an authority on escape lines and may have the answers you are looking for. Keep me informed as to what you find out. You never know, there may be a future blog topic. STEW