My inspiration for our story today came from one our readers. Larry R. contacted me about needing assistance regarding his cousin, Josephine. Working for the American Voluntary Ambulance Corps (AVAC), Josephine was an ambulance driver in France before its surrender to the Germans in June 1940. Larry’s mission has been to obtain official recognition for Josephine and her services to France. I’m happy to say that due to Larry’s considerable efforts, the French government has issued an official letter commending Josephine for her assistance to France.

Like Larry’s cousin, time has condemned the memory of the brave women of Des Rochambeau, or Rochambelles to history. Thanks to author Elle Hampton and her 2006 book, the complete story has been told about Florence Conrad and her Rochambeau ambulance drivers.

Did You Know?

Did you know that eighth graders’ test scores in U.S. history and civics fell to the lowest levels on record? Although some improvement was made during the 1990s, the trend began to reverse itself and for the 2022-23 school year, knowledge of history and civics reached an all-time low. Only thirteen percent of all eighth graders met proficiency standards for history while twenty percent met or exceeded minimum standards for civics studies.

Can we blame the pandemic? Perhaps but trends had been declining pre-pandemic with substantial gaps in student achievement. The study showed that high-performing students maintained their academic levels while low-performing students had significant drops. I’m sure we could probably see the same results in other subjects because of the pandemic’s two to three years of “Zoom” schooling. However, across the board, U.S. history scores were the worst of any subject assessed with civics coming in second worst.

The commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics was shocked at the results and said, “(the scores are) woefully low in comparison to other subjects.” The secretary of education (a federal cabinet position appointed by the president) has implied the blame belongs to the opposition political party.

For those of us who believe history does repeat itself, these educational trends will likely manifest this opinion into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Ambulance Drivers

I suppose the first “ambulance” was probably a cloth hammock tied to two poles and pulled by a human or animal. Records of various methods for transporting the injured date to 900 A.D. However, a radical design change occurred in 1792 when Dominique Jean Larrey (1766−1842), Napoléon’s chief physician, created the ambulance volantes, or “flying ambulances.” These were rapidly mobilized horse-drawn carriages with trained drivers, corpsmen, and litter bearers.

Motorized vehicles were introduced in the late 19th-century and quickly adopted by the military. During the first world war, the Red Cross replaced their horse-drawn carriages with motor vehicles. These new ambulances were able to carry more supplies, advanced medical equipment, and were driven primarily by volunteers (men and women).

Between 1914 and the United States entering the war in April 1917, more than 3,500 Americans volunteered to drive the ambulances for the Allies. Women were not allowed in combat, and they saw this as a way to personally contribute to the war effort. There were many ambulance units including the the American Field Services, Anglo-American Corps, U.S. Army Ambulance Service (USAAS), American Red Cross Motor Corps, the Friends Ambulance Unit (FAU) and of course, Josephine’s organization, AVAC (a.k.a. Norton-Harjes Ambulance Corps) that was founded in 1914.

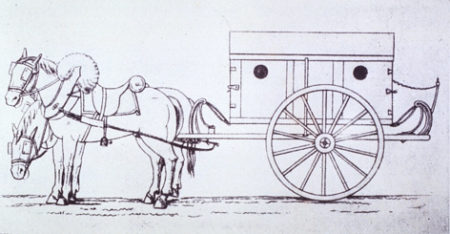

After the start of the second world war in September 1939, physicians were pulled off ambulance duty to serve in the armed forces. However, the need for ambulances was so great that Britain and France converted old vans, hearses, and even police cars. The Order of St. John and the British Red Cross began their efforts to support the necessary ambulance services. However, by the fall of 1940, there was an acute shortage of staff including male drivers. At that point, the call for women volunteers went into high gear. Initially, the women came from the English shires, Scotland (St. Andrews Ambulance Association), the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), and Canada. The volunteers were skilled in driving, auto mechanics (each driver was responsible for maintaining their vehicle), and nursing. In all cases, these were very courageous women who operated under harsh conditions including combat situations. There were times when the ambulance crews offered care to the locals, especially the infirm and elderly.

In response to female “combat” personnel in France in 1939, a general said, “Of course, you can say that we don’t smile on the proposition.” However, by 1943 that attitude changed when Florence Conrad offered the French army a deal it couldn’t refuse.

Florence Conrad

Florence Conrad (1886−1966) was a wealthy American widow living in Paris, France. She had been widowed twice and had a daughter when she was nineteen. Florence was tall, attractive, possessed a very strong will, and as we will see, was quite resourceful. She spoke French fluently but with an American accent.

Along with 25,000 other women during the first world war, Florence volunteered to be a nurse in the Red Cross and served less than two miles behind the front lines. After the war, Florence married for a second time but this time, her deceased husband left her with immense financial fortune. Throughout the 1930s, Florence led quite a social life in Paris as a wealthy widow. That is, until the second world war began in September 1939 and Florence traded her nice clothes for a combat uniform.

After a period of inactivity (i.e., the “phony war”), the Germans invaded France in May 1940 and Florence wanted to repeat her previous war experiences. She began by volunteering to drive valuable artworks in her car from the Louvre to the safety of a country-side château. After this, Florence received permission to serve on the Maginot line where she set up a canteen for off-duty soldiers. The first canteen was very successful and financed with her personal funds as were the next five she established. When Florence found out the men on the front lines had no blankets and were dying of pneumonia, she personally funded the purchase of as many blankets as she could find. When France officially surrendered to the Germans on 22 June 1940, Florence was working in a front-line clinic, but she quickly realized she would be better suited as an ambulance driver. Unfortunately, there weren’t any available ambulances, so Florence sent her friend to Paris to buy one. Over the next nine or so months, Florence ferried the wounded in her ambulance and as an American, the Germans issued her an Ausweis, or official travel pass. Her adventures during this time were quite extraordinary.

By early 1941, Florence was persuaded to return to the United States to warn the Americans about the situation in France. She found the French expatriates in New York were divided into two camps: Gen. Henri Giraud and his First Army and Gen. de Gaulle and his Free French. She put their squabbling to the side and by May 1943, Florence made the decision to form an ambulance unit with women drivers. She would contact the head of the French Free Forces and demand her unit become part of his army. So, Florence began to raise money for the purpose of buying ambulances. First, she approached her wealthy friends and then civic associations as well as other groups. Soon, Florence had enough money to buy nineteen brand-new Dodge ambulances. Now, all she needed were the drivers.

Recruitment and Training

The next step was recruitment and training. Florence used word-of-mouth to spread her message. She also posted advertisements in the French departments of universities. It didn’t take long. University professors signed on as did their students. Women who were heiresses to family business fortunes climbed onboard. Women who were restless and bored with their secretarial jobs joined. Most of the applicants and new recruits were French with about a dozen Americans. Ultimately, the U.S. government refused to allow American women to serve under French command, but they made an exception for Florence. Fifty-one women went on to initially serve in Florence’s ambulance unit. Their primary motivation was to serve France by joining the Free French Forces and participate in the liberation of France.

The training took place in Flushing, Queens on the grounds of the old New York World’s Fair. Their training included auto mechanics, stripping down engines, repairs, and changing tires. Medical training consisted of classes on bandaging, giving shots, taking temperatures, and serving time as volunteers in local hospitals.

Florence by now was fifty-seven and most of the recruits were in their early twenties (the youngest was seventeen). She knew the importance of having a younger second-in-command and soon found the right woman.

Let’s Meet Some of the Rochambelles

Suzanne Rosambert Torrès (1907−1977) was born and raised in Paris. She spoke fluent English as her mother was an American. Suzanne became an attorney known for her intelligence and no-nonsense approach. Separated from her husband who left for New York, Suzanne remained in France running a volunteer ambulance service. By 1942, Suzanne had moved to New York where she was introduced to Florence Conrad at a cocktail reception. Florence sat down with Suzanne and offered her the opportunity to not only join but become Florence’s second-in-command. Suzanne dismissed the offer. She was a Gaullist and complained that half of the women were in Giraud’s camp. (Florence was a Giraudist.) She refused to work with them. Florence wasn’t someone who took “no” as a final answer and she relentlessly pursued Suzanne until one day in July 1943, the young woman walked into Florence’s office suite and signed up to be the commandant’s lieutenant. Her nom de guerre became “Toto.”

Jacqueline (“Jacotte”) Fournier (1910−2008) was an au pair for a French family vacationing in America when the war started. Unable to return to France, Jacqueline took on various jobs before learning about the Free French led by Gen. Charles de Gaulle. She wrote to de Gaulle’s representative in Washington that her desire was to drive an ambulance for the Free French. Jacqueline was turned down because only men were allowed to drive ambulances for the French. Soon afterward, Jacqueline received a call out of the blue from someone named Florence Conrad. Would Jacqueline be interested in joining a new ambulance unit?

Jacqueline Lambert de Guise (?−1996) served as a nurse until November 1944 when she switched to driving an ambulance. Jacqueline followed Leclerc to Indochina and later married war hero Maurice Sarazac (1908−1974).

Leonora Lindsley (?−1945) lived in Paris with her parents prior to the war. After recruiting Leonora, Florence accompanied her new recruit to Saks Fifth Avenue and Brooks Brothers where they bought their gear. Unfortunately, Leonora was not allowed to join the group because she was a U.S. citizen and forbidden to serve in a French military unit. She went on to join the American Red Cross but was able to link up with Florence and the Rochambelles later in the war.

Hélène Fabre was a heiress to a French shipbuilding fortune and one of the youngest Rochambelles. She served as a nurse in Des Rochambeau until the German surrender in May 1945.

Lucienne (“Lulu”) Arpels (1911−c.1996) was the daughter of the co-founder of Van Cleef & Arpels jewelry. After serving as a liaison officer in North Africa for a year, Lulu fled Vichy France and arrived in New York City in September 1941. She signed up with the Free French and learned to drive an ambulance. Joining Florence and the Rochambelles, Lulu elected to stay in North Africa as an aide-de-camp to a senior French officer rather than following the unit to England.

Anne Hastings (1924− ?) was working on her doctorate at Harvard when Florence came calling. Her husband, Wendell Hastings, signed up to work for the Office of Secret Services (OSS), the predecessor to the CIA. She took up training to be a nurse until Wendell saw Florence’s advertisement and suggested Anne get a driver’s license and join Florence’s ambulance unit.

Gen. Philippe de Hauteclocque and the 2e DB

Florence’s next challenge and probably her greatest was convincing the Free French to assign her ambulance unit to one of their military divisions. The Rochambelles shipped out in early September 1943 and eleven days later, they docked in Casablanca. Florence’s unit was not attached to any Free French forces and so, she and Toto went off to see Gen. Marie-Pierre Koenig. The head of the Free French Forces agreed to contact Gen. Jean-Marie de Lattre de Tassigny and Gen. Philippe de Hauteclocque (1902−1947) whose nom de guerre was Leclerc. Florence told Koenig she would rather serve under Leclerc.

Gen. Leclerc commanded the Free French’s new Second Armored Division, also known as the 2e DB (Deuxième Division Blindée) that was assigned to Patton’s U.S. Third Army. Upon hearing the new ambulance unit would have women drivers, Leclerc refused. He only wanted men as drivers since he thought women in his division would be a source of dissension. Florence told the general there would be no ambulances if he didn’t accept the women. Now, Gen. Leclerc was no fool. He needed the nineteen ambulances and so he relented but with a caveat. If the women passed training and maneuvers in North Africa, he would accept them, but they would only be allowed to go as far as Paris and no further. Florence guaranteed her soldiers would not cause him any issues. (Florence allowed the women to only socialize with officers and under direct supervision.) The Rochambelles were initially assigned to the medical battalion’s First Company and neither Leclerc nor his senior officers ever thought their new unit would make it out of North Africa.

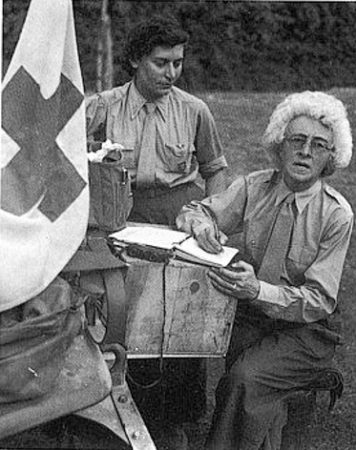

The Rochambelles were housed in an old houseboat in Rabat (capital of Morocco) where their ambulances were parked on the quay. During this time, Florence and Toto continued to recruit. Some of the women left and had to be replaced. Toto was a demanding officer, and she was very particular whom the unit recruited.

After landing in Normandy on 1 August 1944, the Rochambeau unit followed Leclerc and his tanks into Paris in August 1944 and then to liberate Strasbourg on 23 November. The women convinced Leclerc they were too valuable to be left behind and he offered to take them to Germany and after the war ended, French Indochina. (Indochina was a collection of French colonial territories including Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam.) By the end of the war, Des Rochambeau consisted of sixty-five women. Maj. Florence Conrad turned over the unit to Suzanne Torrès in August 1944 and the unit was officially dissolved in September 1945.

One of the Rochambelles was killed, one went MIA (never found), and six were wounded (all but one were able to return to duty).

Des Rochambeau was the first women’s unit to be assigned and integrated directly into a military combat group (as opposed to being an auxiliary non-combat unit). Many of the women were decorated by the Allied nations.

Post-War

Many years after the war, the men and women of the British-led Special Operations Executive (SOE) and French Resistance said the four years of fighting the Germans were the most exciting years of their lives. Anne Hastings of the Rochambelles echoed those sentiments when she said, “I didn’t find life dull at all after that, but it would have been difficult to find anything as exciting.” About fifteen of the women followed Leclerc to Indochina whereas the other women found re-entering civilian life to be difficult. Only five left behind detailed accounts of their days as Rochambelles. Thankfully, Ellen Hampton wrote her book during a time when she could interview many of the surviving members.

One common thread was summed up by Rosette Peschaud: “I was part of the Rochambeau group, I was a Rochambelle, I remained a Rochambelle.”

Suzanne Torrés:

Toto followed Gen. Leclerc to Indochina where she commanded 1,200 medical corps personnel. Divorced from her first husband, Toto married Col. Jacques Massau in 1948. Toto returned to France where she worked for a veterans’ association before following Jacques to various army posts. She published her memoirs in 1969.

Jacqueline Fournier:

Jacotte returned to Paris to care for her ill father and support her mother. She found employment at the Ministry of Defense as a secretary. That lasted nine months before she joined the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) where she spent the remainder of her career. (The OECD was assigned to oversee the implementation of the Marshall Plan in Europe.)

Anne Hastings:

Anne declined to follow Leclerc to Indochina and followed her husband to England. They eventually returned to America where she worked for Harvard University in the archaeology department. According to Anne’s children, after the war, their mother’s threshold for thrills was quite high.

Leonora Lindsley:

In May 1945, Leonora was thrown out of her jeep after hitting a bomb crater and hit her head. Never recovering consciousness, Leonora was twenty-eight when she died on the day the Germans surrendered. She is buried at the Lorraine American Cemetery in France alongside more than ten thousand military dead.

Florence Conrad:

Florence married Col. Paul Lannusse and retired to the Loire Valley. She died in their château and was buried in her Rochambeau uniform and given full military honors.

Phillipe Leclerc:

Gen. Leclerc left the 2e DB on 22 June 1945 and was assigned to Indochina. Two years later, Leclerc died in a plane crash while on duty. He is considered a French national hero.

https://www.2edb-leclerc.fr/les-unites-de-la-2db/

Why the Name “Rochambeau”?

At this point, you might ask about the origin of the name “Rochambelle.” The women originally wanted “Lafayette,” but the name had been used in the first world war by the Escadrille Lafayette. So, they went with the second-best option. They decided to refer to the unit as Des Rochambeau in reference to Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau (1725−1807).

The count was a French nobleman and general in the French army. King Louis XVI sent him to America to join Gen. George Washington’s Continental Army. Interestingly, Rochambeau’s aide-de-camp and interpreter was Axel von Fersen (click here to read the blog, Marie Antoinette’s Lover). Washington and Rochambeau became close friends, and the experienced French soldier became a trusted military advisor to the Americans. Rochambeau led French infantry troops to Yorktown in 1781 and helped the Americans win their revolution. The count returned to France just in time for the French Revolution. Remarkably, despite his support of the monarchy, Rochambeau survived the revolution and the period known as “The Terror” to retire peacefully. (refer to our books, Where Did They Put the Guillotine?) Today, the “Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route” is a national historic trail encompassing more than 680 miles of land and water trails through nine states and Washington D.C.

Next Blog: “The Sussex Plan and Three Very Brave Women”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Brunet, Pauline. Les Rochambelles: Ambulancieres de la Division Leclerc. Evansville, IN: Memorabilia, 2021. (French edition.)

Cobb, Matthew. Eleven Days in August: The Liberation of Paris in 1944. Simon & Schuster: London, 2013.

Conrad, Florence and Jean Pages. Camarades de Combat. Ann Arbor, MI: Brentano’s, 1942. (French edition.)

Hampton, Ellen. Women of Valor: The Rochambelles on the World War II Front. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2021. (First edition was published in 2006.)

Massu, Suzanne. Quand j’étais Rochambelle, de New York à Berchtesgaden. Paris: Grasset, 1969. (French edition.)

Morris, James McGrath. The Ambulance Drivers: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and a Friendship Made and Lost in War. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2017.

Popham, Hugh. The FANY in Peace and War: The Story of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry 1907−2003. Yorkshire: Pen and Sword, 2009.

Sardella, Jean-Yves. Les Rochambelles: ces femmes combattantes au sein de la 2o D.B. En mémoire de l’une d’entre ells, inhumée à La Chavanne. Mémoires de L’Académie des Sciences, Belles-Lettres et Arts de Savoie: 2019−2020, Tome IV, Pages 375−389.

WW2TV/YouTube:

The Rochambelles – Women in the French Second Armored Division. Click here to watch the video.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I recently returned from Akron, Ohio where we attended my fiftieth high school reunion (Firestone High School).

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank our friend, Fabrice D., for including us on the distribution list of an e-mail he sent out that addressed the 19 May 2023 commemoration ceremony for unveiling a plaque in Paris dedicated to Section Office Lilian Vera Rolfe (Agent “Nadine” of French Section, Special Operations Executive). There were many photographs and short videos attached. I believe the plaque and the ceremony were sponsored by Secret WW2 – The Secret WW2 Learning Network. Click here to visit the web-site. It is a UK educational charity.

Fabrice mentioned that Francis J. Suttill is trying to get a memorial plaque to his father at the site (18, rue de Mazagran, Paris 10e) where his father, head of the SOE Prosper circuit, was arrested by the Gestapo on 24 June 1943. (His father, Maj. Francis Suttill was executed at KZ Sachsenhausen along with others including Capt. W. Grover Williams – click here to read the blog, The Racer, Spy and Erotic Model.) We will keep in touch with Fabrice and Paul to see what assistance Francis needs to make the plaque a reality.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books (in our case, it is Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?). The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please contact Stew directly for purchase of books, Kindle available on Amazon. Stew.ross@Yooperpublications.com or Contact Stew on the Home Page.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross

A well deserved tribute to these dedicated and courageous women. Thanks.

On a separate issue, it’s my opinion that state education curriculum is to blame for the lack of history and civics in schools. Our grandson, who is in high school, has no courses in these subjects. I can only why. Something is very wrong and needs to be fixed.

Hi Greg, Always look forward to hearing from you. I appreciate your comments and support. STEW