Our story today originated as a result of an e-mail from one of our readers, Andrew B. who read our blog Double Agent or Bad Neighbor? (read here). Andrew pointed out that I had “missed a key point, 140 meters away from (where) Déricourt, lived Yvonne Grover-Williams.” Andrew went on to briefly describe Yvonne’s role during the German occupation of Paris.

Andrew was right about me missing this one on Yvonne and her story. To be honest, I had never run across this woman or her husband, William Charles Frederick Grover-Williams, head of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) CHESTNUT circuit in Paris. During the occupation, Yvonne lived at 21, rue Weber which was around the corner from Henri Déricourt’s apartment about five hundred feet away at 58, rue Pergolèse (and next door to the renown Nazi spy catcher, Hugo Bleicher) and not too far from Avenue Foch where various Gestapo units set up their offices including the infamous interrogation and torture cells on the fifth and sixth floors at number 84.

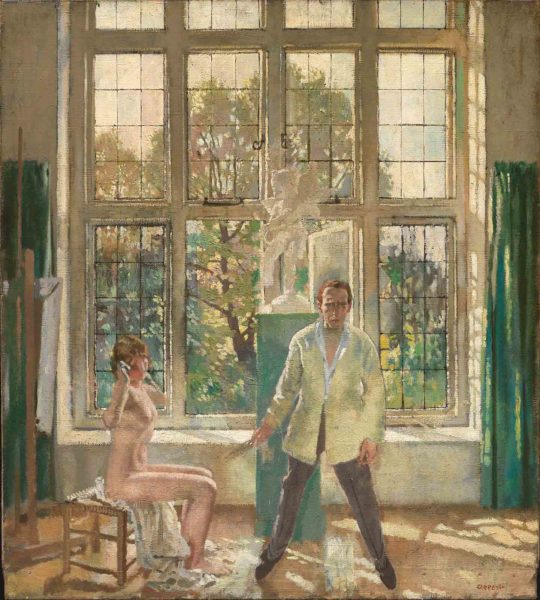

Well, that sent me down, yet another rabbit hole and I discovered a wonderful book by Joe Saward called The Grand Prix Saboteurs. Part of the story includes the years Yvonne spent as Sir William Orpen’s mistress, modeling for his paintings in some very suggestive nude poses. Then, with Orpen’s approval, she married the couple’s chauffeur.

Did You Know?

Did you know that a gruesome discovery was made several years ago in Berlin at the Charité University Hospital? In several of my past blogs, I’ve talked about the Nazi executions (i.e., beheadings) of women prisoners − principally political resisters − at Plötzensee Prison (read The Nazi Guillotine blog here). After their executions, the bodies were sent over to the Berlin Institute of Anatomy at Charité where Dr. Hermann Stieve (1886-1952) was an internationally acclaimed anatomist. His research specialized in the effects of stress on the menstrual cycle. Before the Nazis came to power in 1933, women were not executed in Germany. However, that changed quickly under the Nazi party. Approximately 182 women were tried before a Nazi court (read Hitler’s Blood Judge blog here), found guilty, and executed. Stieve performed dissections on their reproductive organs to support his research. After he was finished, the remains were discretely cremated and disposed of in locations that were never disclosed to the families. Some of these victims included the women of the Red Orchestra resistance organization (read Die Rote Kapelle blog here) while others were convicted of innocuous crimes including distributing leaflets.

In 2016, more than three hundred microscope slides once belonging to Stieve were discovered at Charité. These were samples taken from the bodies he dissected during the war. They were stored in small black boxes with the names of the victims. On 13 May 2019, a small coffin containing the slides was buried at Berlin’s Dorotheenstadt Cemetery in a grave near one of the memorials to the victims of the Nazis. It is hoped that this will give some closure to the victims’ families as well as an effort to ensure the Nazis’ crimes will not be forgotten. Despite joining right-wing organizations during the interwar period (the time between World Wars I and II) and becoming a strong supporter of Hitler, Dr. Stieve never joined the Nazi party. As a result, he was never tried for war crimes.

Let’s Meet Yvonne Aupicq

Yvonne Aupicq (1896-1973) was born in Lille, France to Joseph Aupicq, a schoolteacher and Laetitia who worked as a housekeeper. Many accounts of Yvonne’s life mention her father was mayor of Lille and her last name was spelled Aubicq. However, her birth certificate and other historical records do not substantiate either of those assertions.

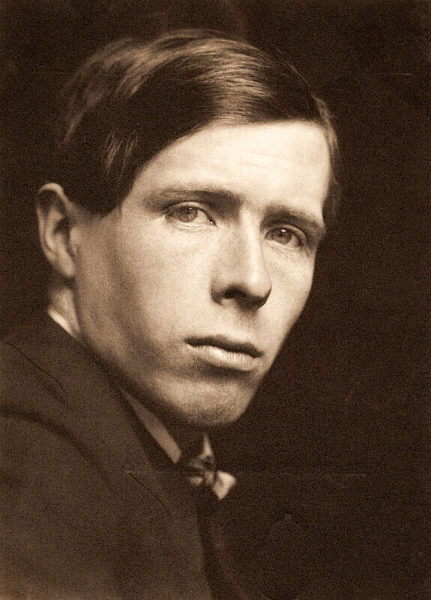

Yvonne was a strikingly beautiful woman with deep blue eyes and golden curly hair. She worked at a hospital during World War I which is where she met the famous Irish portrait artist, Major William Orpen (1878-1931), who was assigned to the war’s Western Front as an official Allied war artist. Learn more about Major William Orpen here.

After the war, around 1918, Yvonne and the newly knighted Sir William began a ten-year affair during which she posed for many paintings including “The Refugee,” “Nude Girl Reading,” “The Disappointing Letter,” and “Early Morning.” During this time, the wealthy couple lived in Paris since Orpen had been appointed the “Official Artist” of the Paris Peace Conference. The artist and Yvonne lived in the fashionable 16th arrondissement at 21, rue Weber where he maintained his studio. Sir William bought a black Rolls-Royce and in 1919, hired a dashing young man named William Grover to be his chauffeur.

Let’s Meet William Charles Frederick Grover

William Charles Frederick Grover (1903-1945) was born in France to an English horse handler (Frederick) and a French woman (Hermance Dagan). Frederick Grover and the family followed his Russian benefactor to Paris but when World War I began, “Willy” was sent back to England ⏤ followed shortly thereafter by the rest of the family ⏤ where he developed a fascination for automobiles both mechanically and as a driver. Willy Grover was thirteen when his sister’s boyfriend taught him how to drive a Rolls-Royce. Two years later, Willy bought an Indian motorcycle and began racing it using the name of “W. Williams” to keep his dangerous sport a secret from his mother and the rest of the family.

He moved back to Paris and landed a job in 1919 as Orpen’s chauffeur driving the black Rolls-Royce. Over the next nine years, Willy became close to Yvonne and by the time Orpen and Yvonne broke-up in 1928, it was only a matter of a year before the chauffeur married Yvonne with her former lover’s permission and presumably, a wedding gift of the black Rolls Royce (sadly, Orpen would pass away three years later). Soon after, Willy and Yvonne changed their last name to Grover-Williams.

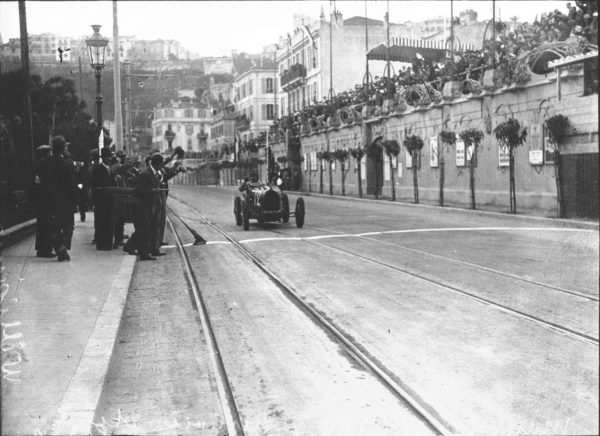

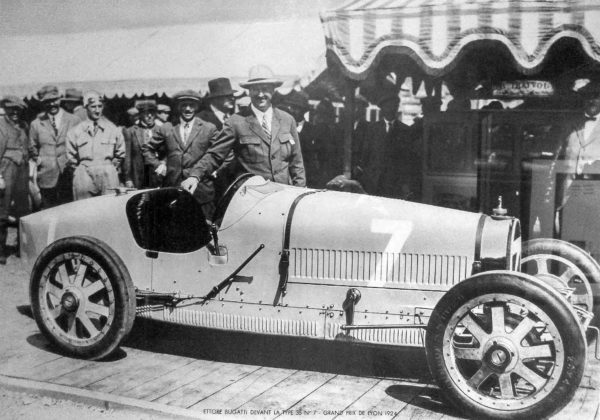

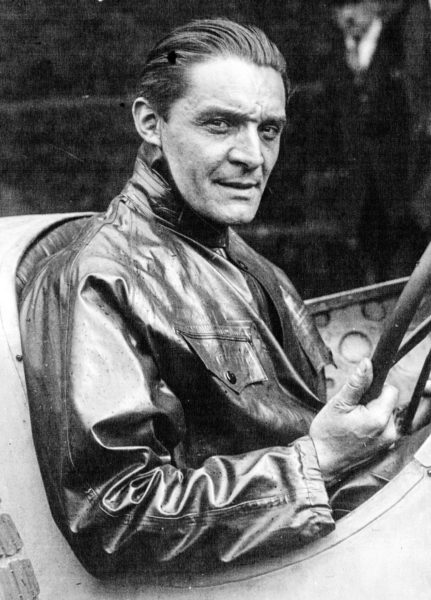

The Monaco Grand Prix and a Racing Career With Bugati

While our fascination with Willy and Didi (this is the name Willy called Yvonne) stem from their work as spies during the Nazi occupation of France, history seems to remember Grover-Williams more for his exploits as a race car driver. By 1926, W. Williams was racing his Bugatti in events all over France including the Monte Carlo Rally, the French Grand Prix (winning in 1928 and 1929) and culminating in his victory at the inaugural 1929 Monaco Grand Prix. Watch video clips of the race here.

Willy raced as an Englishman and his Bugatti was painted in what famously became known as “British racing green.”

Willy and Didi were financially well-off, and they maintained homes in Paris (the Rue Weber house which Orpen had gifted to the couple) and the resort town of La Baule, a seaside resort in southern Brittany near Sainte-Nazaire (where Didi bred and raised Highland terriers). Grover-Williams continued to win prestigious races until the early 1930s when his racing career waned, and he retired from racing in 1933 to live the life of a wealthy gentleman of leisure. Unfortunately, a war broke out six years later which ultimately cost Willy his life.

Second World War

After the Germans occupied France, Grover-Williams made it back to London while Yvonne remained in Paris. Quickly recruited by the SOE team because of his fluency in English and French, Grover-Williams underwent training with the intent of setting up a SOE intelligence network in France. After completing his training, Willy (or I should say, “Sébastien”) parachuted into France at the age of 39 to begin his SOE assignment. His first priority was to begin recruiting members to join his circuit code named CHESTNUT. Unfortunately, he was lacking a radio operator and without any contact with London, Sébastien and his circuit were neutralized.

One of the first agents Willy recruited was Robert Benoist, France’s top race driver during the 1920s and a top competitor for W. Williams. Without a radio operator, CHESTNUT was limited in its ability to gather intelligence or perform small acts of sabotage. They were told to essentially become a “sleeper” cell, but Willy continued to recruit new agents as well as CHESTNUT becoming a “parachute reception” group for other SOE agents dropped into France. Willy was able to stay with Yvonne but eventually, he secured an apartment under the premise he was working as an engineer. Didi would visit him regularly as his “girlfriend” (you could never trust an apartment concierge). Benoist’s cover was a customer service representative for Ettore Bugatti’s Paris car showroom and store. Mr. Bugatti provided Benoist with all the proper documentation to allow Benoist to travel wherever he wanted to go.

Didi supported her husband’s resistance activities by offering her residence as a “safe house.” She also performed other small jobs but was really never heavily involved on a day-by-day basis. However, Didi became friends with Noor Inayat Khan, a SOE agent who had parachuted into France to join the PROSPER circuit as a radio operator. Unfortunately, days after arriving, the Gestapo began arresting PROSPECT’s agents. They soon became aware of Noor and placed a high priority on arresting her to obtain the code book (Germans were very effective at taking captured radios and codes and then sending false messages to London under the disguise of the compromised radio operator). The Gestapo learned that Didi knew Noor and they arrested Willy’s wife in September 1943 for the purpose of interrogating her about Noor’s whereabouts. Didi was sent to Fresnes prison without revealing any information and on 8 October 1943, the Germans released her.

Capture and Arrest

Willy and Robert Benoist interacted with several of PROSPER’s agents including its founder, Francis Suttill. PROSPER was considered a huge success by London but it had become quite large which increased the chances of German infiltration and betrayal. During the early summer of 1943, PROSPER had been betrayed and subsequently, decimated by the Gestapo with most of its agents arrested. The Gestapo then turned their attention to CHESTNUT.

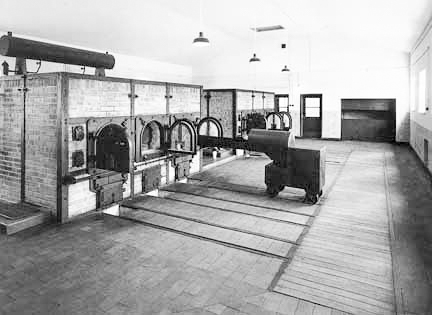

It is thought that Benoist’s brother, Maurice, betrayed CHESTNUT and on 2 August 1943 while meeting at the Benoist farm in Auffargis, Willy was captured by the Gestapo. Robert Benoist escaped and ultimately made it back to London where he underwent formal SOE training. Willy was mercilessly tortured by the Germans, but he revealed nothing and eventually was transferred to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Willy was able to survive Sachsenhausen until March 1945 when his name was added to the list of prisoners (including Francis Suttill) who were to receive “special treatment.” Two months before the Soviets liberated Sachsenhausen, Willy was executed either by a shot to the back of the neck, hanging, or lethal injection. As a Nacht und Nebel prisoner (Night and Fog read blog here), no trace of his existence remained.

Benoist returned to France in October 1943 and operated a new circuit, CLERGYMAN, until February 1944 when he returned to London a second time. A month later, Benoist went back to France to work as a résistant in the Nantes area. On 18 June 1944, Benoist was arrested by the Gestapo and sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp where he was incarcerated with other members of the “Robert Benoist Group” and SOE agents such as Frank Pickersgill (ARCHDEACON), Forrest Yeo-Thomas (RF Section), and Maurice Southgate (STATIONER). Three months later, Benoist was one of sixteen prisoners called to report to the camp’s Leichenkeller or, “corpse cellar.” Robert Benoist was murdered in the execution chamber on 9 September 1944 and like Willy Grover, the Nazis left no trace of his existence.

Post-War

After the war, Didi continued living at 21, rue Weber and she was granted a government pension as the widow of a British soldier. She ultimately sold the house and moved to Beaulieu where her summer home was located. Didi’s last stop was a move to Normandy where she boarded and bred her beloved terriers, much like she had done with Willy during the inter-war period. Yvonne Grover-Williams died in 1973 at the age of 77 in Évreux, France.

Antiques Roadshow and “The Copy”

A gentleman showed up at a recent BBC program of Antiques Roadshow with a copy of “The Refugee” by Sir William Orpen. His uncle had purchased the painting many years earlier and upon the death of his relative, the gentleman inherited the picture of a young Yvonne Aupicq. The painting wasn’t taken seriously by the show’s experts until further research was conducted. Lo and behold, the painting was an original Orpen and deemed to be worth £250,000 ($321,500). It seems that Orpen painted several portraits of Yvonne using a similar pose. Orpen painted the original while working for the government as a war artist. When he showed them the painting, he tried to pass it off as a portrait of a condemned spy (he was only allowed to produce artwork associated with the war). His farce was discovered and the only thing that kept him from a court martial was the intervention of his friend, Lord Beaverbrook. The original portrait was entitled “The Spy” but was quickly renamed “The Refugee.” The painting on the Antiques Roadshow was given to Lord Beaverbrook by the artist as a gift and subsequently sold to the gentleman’s uncle. The first portrait is on display at the Imperial War Museum. Watch the episode here.

✭ ✭ ✭ Learn More About Mr. & Mrs. Grover-Williams ✭ ✭ ✭

Ryan, Robert. Early One Morning: A Novel (The Secret War Trilogy Book 1). New York: Open Road, 2002.

Saward, Joe. The Grand Prix Saboteurs. London: Morienval Press, 2006.

Mr. Saward has written a wonderful book. It is factual, easy to read, an interesting account of the lives of people who have slipped into the dark recesses of history, and his research is excellent. The book is a result of eighteen years of exhaustive research and investigation. Mr. Saward is a journalist who reports on international car racing. His account of the European racing circuit in the 1920s and 1930s and how W. Williams, Robert Benoist, and Jean-Pierre Wimille (winner of the 1939 Le Mans 24-hours) interacted is fascinating.

I have not read Mr. Ryan’s novel which is based on Willy’s life.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are doing what you are probably doing: looking ahead to the New Year and prioritizing our activities (“retirement” seems to be just as busy as I remember when we both had our careers and were raising the children). Our days, weeks, and months boil down to four activities:

- Writing these blogs

- Lecturing

- Writing the new book, Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?

- Traveling

Oh, I forgot one. The newest addition to our family is Stella, our seven-month-old Beagle puppy. That takes us a couple of minutes each day.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I appreciated Karen U. for contacting me in regard to finding the right private guide for her trip to Paris this year. Karen is an author and will be researching her next book in June. It seems she remembered my advice in Where Did They Put the Guillotine? Volume One and the walks through Versailles Village and the palace. I recommended that you do not visit Versailles without a credible guide. I was very pleased to be able to introduce Karen to Raphaëlle Crevet whom most of you know as our “go-to” guide in Paris and the city’s surrounding areas. I’ve referred others to Raphaëlle over the years and the feedback is always that Raphaëlle exceeded all expectations (and those expectations must have been high since I set them that way). Good luck Karen with the new book and let me know when it’s published.

This blog is a great example of one of the ways we come up with topics for our blogs, presentations, and yes, even some of the stops in our books. Thank you again, Andrew, for surfacing Yvonne and her story.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright ©2020 Stew Ross

That’s very kind of you…

Joe, I enjoyed the book. STEW

The painting featured on the BBC Antiques Roadshow subsequently went for restoration which revealed it was not by Orpen. It’s a pity the BBC don’t update their information!

Hi Dominic; Good to hear from you again. I agree. It’s too bad The BBC doesn’t update information concerning past shows. At least reputable newspapers print corrections to their articles. STEW