By 1944, the war wasn’t going well for Hitler and his military. In fact, a year earlier, people began reaching the conclusion that Germany might eventually lose the war. How was it that within less than five years after conquering almost all of Europe that Hitler’s armies, navy, and air force were on a downward spiral toward defeat? There were many reasons including what historians now chalk up to the Führer’s military decisions that were huge strategic mistakes. However, during the early years of World War II, it seemed as though the German juggernaut was invincible and leading the pack was Hermann Göring’s Luftwaffe (i.e., the German air force).

Göring was so confident of his pilots and planes and their supremacy in the sky that he vowed Germany would never be bombed. Addressing the Luftwaffe when the German air force was at the peak of its power, the antisemitic and future generalfeldmarschall and Hitler’s second-in-command made this promise to the German people:

“No enemy bomber can reach the Ruhr (valley). If one reaches the Ruhr, my name is not Göring. You may call me Meyer.”

⏤ Hermann Göring

September 1939

As Allied air forces increased their bombing activities over Berlin and the Ruhr Valley in early 1944, air raid sirens in the city were going off on a nightly basis. It didn’t take long for Berliners to begin calling the sirens, “Meyer’s Bugle.”

Did You Know?

Did you know that the last surviving female agent of the British-led Special Operations Executive (SOE) passed away in October 2023? Phyllis “Pippa” Latour, MBE (1921−2023) was born in South Africa to a French father and British mother. She spoke fluent English and French along with Arabic, Swahili, and Kikuyu. After war broke out, Phyllis joined the British Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and became a balloon operator and mechanic. In 1943 she applied to and was accepted by the SOE’s F Section. Dropped into Normandy, France in early May 1944 as a wireless operator, Phyllis (nom de guerre: Geneviève) was part of the D-Day underground support forces behind enemy lines and she was responsible for gathering and transmitting intelligence on German positions as well as landing sites for equipment air drops.

Despite mediocre and somewhat dismissive SOE training reports, Phyllis’s performance in the field was superb. She was innovative, able to adapt quickly to dangerous situations, and never lost her nerve ⏤ she was fearless. Phyllis became the wireless operator for the reconstituted SOE Scientist circuit led by Claude de Braissac (1907−1974) and included his sister, Lise de Braissac (1905−2004). Quite a bit of her work between May and August (when she returned to London) was with the Maquis (French guerilla résistants).

Like most British World War II veterans, Phyllis honored her oath to the Official Secrets Act and never divulged her wartime experiences to anyone including her children. It has only been in the recent past that her wartime files were opened and made available to the public. Phyllis passed away in New Zealand.

Over her life, Phyllis was awarded numerous honors including the MBE, Légion d’honneur, and Croix de guerre. She was certainly a member of the world’s “Greatest Generation.”

Hermann Göring

Hermann Göring (1893−1946) was a World War I fighter pilot who attained ace status and commanded Jagdgeschwader 1, or the “Flying Circus” fighter squadron formerly led by the “Red Baron,” Manfred von Richthofen (1892−1918). As the war came to an end, Göring refused to surrender his aircraft and ordered the pilots to crash land their planes to keep them from the enemy.

After the war, Göring did not abandon his aviation ambitions. Barnstorming, working as a private pilot, and corporate salesperson for Fokker were some of the endeavors the former fighter ace pursued in Denmark and Sweden before returning to Germany in 1921. While studying in Munich, Göring met Adolf Hitler (1889−1945) in 1922 and immediately joined Hitler’s fledgling right-wing National Socialist German Workers Party, or NSDAP. Göring embraced Hitler’s view that Germany lost the war because of the betrayals of Jews, Communists, and German politicians. He identified with Hitler’s territorial aspirations as well as the Nazi party’s policies regarding racial purity, eugenics, and the elimination of Jews, Romani, Poles, mentally ill, disabled, and other Untermensch.

Göring was extremely intelligent, devious and cunning, ambitious and power hungry, a narcissist, brutal, egotistical, a drug addict, an art thief and plunderer of Jewish citizens’ property, and above all, a murderer. He was one of the top Nazis responsible for the theft of some of the world’s greatest paintings, statues, and various art works ⏤ many of which have never been recovered or returned to their rightful pre-war owners. He visited Paris twenty-one times for the purpose of selecting artwork for his personal collection as well as Hitler’s future art museum in Linz. This was artwork appropriated from Jews, art galleries, governments, and other private collections (click here to read the blog, The Monuments Woman).

Click here to watch the video Hermann Göring–WWI Fighter Ace.

Interwar Years

In 1922, as an early supporter of Adolf Hitler and war hero, Göring earned a place in Hitler’s immediate circle of friends and advisors. His first command position was to lead the paramilitary Sturmabteilung (SA) otherwise better known as the Brownshirts. The following year, Göring participated in the failed Munich Beerhall putsch and was forced to flee the country until 1927 when he returned under a general amnesty. Wounded in the putsch, Göring became a morphine addict and did not kick this drug habit until his imprisonment in Nuremberg in 1945. He rejoined the NSDAP and was instrumental in elevating Hitler to power. In 1932, Göring became president of the Reichstag before creating the Gestapo and turning it over to Heinrich Himmler (1900−1945) two years later. Together with Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich (1904−1942), Göring set up the original concentration camps. However, Göring’s greatest on-going responsibility was leading the German Luftwaffe between 1935 and 1945.

After Hitler’s ascent in 1933 as chancellor and then in 1934 as Führer, Germany began to rearm in direct violation of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. Pilots began to train in secret and by 1936, Göring was ready to test his “new” Luftwaffe. (The treaty prohibited Germany from maintaining an air force.) During the Spanish Civil War (July 1936 to April 1939), the Condor Legion was created, and Göring’s Luftwaffe used the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive bomber, Messerschmitt BF-109 fighter, and Heinkel 111 bomber against the Republicans as lethal demonstrations of German air power. (The town of Guernica was destroyed, and 300 civilians were killed.) Göring and the Condor Legion used six hundred planes including pilots who had trained secretly in the Soviet Union.

From the perspective of the Spanish dictator, Francisco Franco (1892−1975) and his Nazi friends, the results were impressive. These same Luftwaffe tactics would be used again in May 1939 when Göring’s planes were front and center when Hitler invaded France and the Low Countries. By this time, Göring’s reputation with the Nazis and the German people had been substantially enhanced and Hitler promoted him to generalfeldmarschall and anointed the corpulent Göring as his second-in-command and successor.

Göring and His Luftwaffe

After invading Poland on 1 September 1939 and beginning World War II, Germany went into a stagnant period referred to as La drôle de guerre, or “The Phony War.” However, on 10 May 1940, the German army and Luftwaffe suddenly attacked and invaded France (capitulated 22 June) and the Low Countries including the Netherlands, Belgium (surrendered 28 May), and Luxembourg (surrendered 10 May).

The Luftwaffe was an instrumental and deadly force to be reckoned with by the soon-to-be occupied countries. The fiercest demonstration of the dive bombers’ destructive bombs was the attack on Rotterdam on 14 May. Known as the “Rotterdam Blitz,” the four-day event resulted in the destruction of the city center and the deaths of more than 1,150 people with 85,000 left homeless. Threatened with similar destruction of other cities, the Dutch surrendered on 15 May.

Another example of the ruthlessness of the Luftwaffe took place just before the Germans marched into Paris on 14 June 1940. Two million Parisians fled the city to join the millions of other Low Country refugees on foot, bicycle, automobiles, or any other form of transportation with wheels that could take them south away from the invaders. (It is estimated that ten million people were on the roads.) It was almost impossible to move forward due to the congestion. It took ten hours to go thirty kilometers (18.6 miles). The fleeing refugees were sitting ducks as the Luftwaffe planes strafed the roads and adjoining countryside killing helpless men, women, and children.

So, by mid-1940, Göring and his Luftwaffe were the darlings of the German military, and much was expected of them. Hitler was determined to invade England (“Operation Sea Lion”) and ordered the Luftwaffe to clear the skies of British planes. Göring promised his boss that he would eliminate the RAF within days (“Operation Eagle”). Unfortunately for Göring and his ambitions, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) stood tall for almost four months (10 July – 31 October 1940) and defeated the superior forces of the Luftwaffe during the air-to-air combat known as the “Battle of Britain.” Hitler was furious and ultimately abandoned the plan to invade the island.

Winston Churchill summed it up: “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” What Churchill didn’t know at the time was that Hitler began to lose confidence in Göring with Luftwaffe failures in Russia (e.g., the Stalingrad airlift) and its inability to defend Germany from Allied bombing attacks compounding Hitler’s personal attacks on the competence of his second-in-command.

RAF Battle of Berlin

The first bombing of Berlin took place on the night of 25 August 1940 in retaliation for errant Luftwaffe planes dropping bombs on London the night before. Churchill was furious and ordered the attack. Very little damage was done other than kill an elephant in the Berlin Zoo. However, Hitler went into one of his rages blaming Göring and the Luftwaffe for allowing the RAF planes to reach Berlin let alone drop bombs. Göring must have been quite embarrassed especially as one year earlier he promised to change his name to Meyer if a bomb was ever dropped on Germany. Hitler was so enraged that he ordered the Luftwaffe to bomb London every night in what became known as the “London Blitz.”

Click here to watch the video The First RAF Raid on Berlin.

The Battle of Berlin was a British bombing campaign against Berlin between November 1943 and March 1944 (not to be confused with the Soviet Battle in Berlin in April/May 1945). It was led by British Bomber Command and Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris a.k.a. “Bomber Harris” (1892−1984). Primarily a British operation, participants included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Poland. Churchill did not believe in flying during daylight so the British bombed by night while the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) bombed by day.

The first raid of the battle occurred on the night of 18/19 November 1943 when 440 Lancaster heavy bombers attacked Berlin which was clouded over resulting in minimal damage. Four nights later, the second raid was undertaken and was successful in causing extensive damage to the central city including severe damage to the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. Night after night, bombs from 400 to 800 bombers were targeting the Berlin rail system, nearby industrial plants and unfortunately, civilian targets that rendered about a quarter of Berlin’s living facilities uninhabitable. The last raid was in March 1944 when the Allies began to focus everything it had on the upcoming June invasion called “Operation Overlord.” Despite the high cost of lost planes and airmen, Bomber Command’s objective of getting Germany to surrender was not achieved. The morale of the Berliners remained intact, and the city was not destroyed.

Click here to watch the video Bombing Berlin with Ed Morrow of CBS – War Against Humanity 089.

After those first bombs fell on Berlin in 1940, Hitler ordered six flak towers to be built around the city. Due to a lack of resources, only three Berlin towers were ever constructed. (Hamburg had two and Vienna had three.) The first Flakturm I (i.e., flak tower) was completed in April 1941 and located in the center of the Berlin Zoo (where the Hippopotamus enclosure is situated today). It was built to protect the center of the city where the government buildings were located. The tower was destroyed in 1947. Flakturms II and III were built within a year of the first tower. Flakturm III, located in Humboldthain Park, is still standing. Flakturm II, located in Volkpark Freidrichsain, was also used to shelter some of the most valuable artwork stolen by the Nazis. After the war, the Soviets destroyed the flak tower but only after they appropriated the artwork and took the paintings and sculptures back to Moscow. The three flak towers also served as air raid shelters for Berliners.

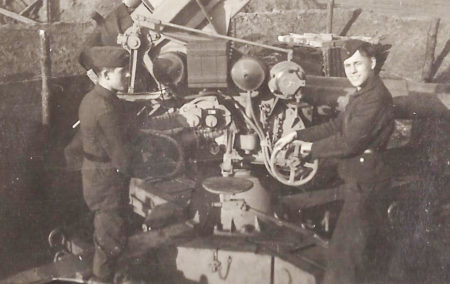

Defenses within the city included anti-aircraft guns placed on top of the towers, searchlights, barrage balloons, and intercept fighter aircraft stationed nearby. The 88mm anti-aircraft guns provided most of the defense artillery and they were arranged in 100 batteries around the city. Each battery had searchlights, radio telemetry, and between 16 and 24 artillery guns including the acht-acht, or “eight-eight” that could fire fifteen rounds per minute with a horizontal range of 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) and almost 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) in the sky. The author and journalist, William Shirer, noted that “The concentration of anti-aircraft fire was the greatest I’ve ever witnessed.” Berliners believed that as long the guns were firing, they were not in danger. (The Luftwaffe did not contribute much to the defense of the city.) British aircraft and airmen casualties were higher than Bomber Harris had envisioned. In one raid alone, of the twenty-five bombers that reached the city, ten were lost.

By the winter of 1940/41, air raids on the capital city were becoming more frequent and Berliners blamed the once adored generalfeldmarschall for his failures to protect them from the bombs. In fact, they described the air raid sirens as “bugles” and publicly began calling the field marshal “Meyer.”

By mid-1944, Göring’s Luftwaffe was virtually non-existent. One of the reasons for the success of the Allied invasion on 6 June was the relative lack of German air support for its ground troops defending the coastline of Normandy. As the Allies introduced new aircraft (e.g., P-51 Mustang), their bombers penetrated deeper and deeper into Germany including Hitler’s capital city. As time went on, Göring was excluded from top-level staff meetings after losing Hitler’s confidence and he began to retreat from the day-to-day operations of the Luftwaffe.

Fall of Berlin

There was another battle for Berlin. It began on 23 April 1945 when Soviet forces began to penetrate the outer suburbs of the city. It ended on 2 May 1945 when the German commanding officer surrendered to the Soviet 8th Guards Army, part of Marshal Zhyukov’s 1st Belorussian Front. Once again, Göring’s Luftwaffe was nowhere to be seen in the sky or on the ground. They had run out of planes and pilots.

However, Berlin’s fall to the Soviets is a story for another day (and blog).

Nuremberg

As one of the senior Nazi officials put on trial at Nuremberg, Göring was charged with four counts including crimes against humanity (click here to read the blog, Courtroom 600). He was tried and convicted on all counts and sentenced to death. Hours before he was to be hanged on 16 October 1946, Göring committed suicide. Cremated, his ashes along with those of the other nine executed men were thrown into the river Isar.

Next Blog: “No 30 Commando”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Anonymous. Translated by Philip Boehm. A Woman in Berlin: Eight Weeks in the Conquered City, A Diary. New York: Picador, 2005. Original edition published in Germany by Eichborn AG, 2003. (The author was eventually identified as Marta Hillers.)

Beevor, Antony. The Fall of Berlin 1945. London: Penguin Books, 2003.

Fleming, Nicholas. August 1939: The Last Days of Peace. Pasadena: Davies Publishing, Inc., 1979 (Göring quotation, Page 171).

McCormack, David. The Berlin 1945 Battlefield Guide: Part 2 The Battle of Berlin. Charleston, S.C.: Fonthill Media LLC, 2019.

McDonough, Frank. The Gestapo: The Myth and Reality of Hitler’s Secret Police. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2017 (Original edition published in London by Coronet, 2015).

Moorhouse, Roger. Berlin at War. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

O’Donnell, James P. The Bunker. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1978.

Le Tissier, Tony. Berlin Battlefield Guide: Third Reich and Cold War. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2008.

Mr. Moorhouse’s book, Berlin at War, brings you a war-time perspective within Germany and in particular, Berlin residents. It is a unique view as most books concentrate on lives of civilians in the occupied countries, Great Britain, and America. The inspiration for this blog came from Mr. Moorhouse’s book.

Mr. McDonough’s book, The Gestapo, focuses on the secret police operations inside Germany whereas most books focus on Gestapo activities in the occupied countries.

A Woman in Berlin was written by a young woman who kept a diary of her experiences during the Battle in Berlin and early Soviet occupation. It was very controversial for its time due to the graphic depictions of Soviet atrocities including the raping of more than 100,000 Berlin women and girls.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are preparing for a busy 2024. We have four international trips planned and in-between, I must make sure we don’t miss our bi-weekly deadlines for the blogs. It’s been more than ten-years of writing these blogs and I’m determined to never miss a deadline. Oh, and then there’s this little issue of getting volume two of the Nazi occupation book finished. Wish me luck!

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

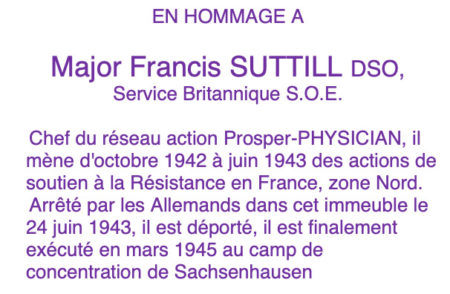

Some of you may remember our blog, The Rochambelles (click here to read the blog). In this section of that blog, I mentioned how Francis Suttill Jr. was trying to obtain permission to have a commemorative plaque attached to the building where his father, a SOE agent, was captured by the Gestapo. (Suttill Sr. was deported to KZ Sachsenhausen where he was executed.)

I’m very pleased to report that permission from the building owner (18, rue de Mazagran) and the Paris municipality has been received. A ceremony is normally held at the building for the plaque unveiling. It is hoped to have this ceremony in 2025, on or near the 25 March date of Suttill’s execution. Sandy and I will plan on attending.

Thanks to all of you who reached out to us in 2023. It is always wonderful to hear from you.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Shepherd.com is like wandering the aisles of your favorite bookstore.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Check out Stew’s new bookshelf on the French Revolution.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please contact Stew directly for purchase of books, Kindle available on Amazon. Stew.ross@Yooperpublications.com or Contact Stew on the Home Page.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2024 Stew Ross

Hello,

thank you very much for the interesting Blog “Meyer´s Bugle”. Two short remarks to the pictures of Herr Radtke. It shows first an anti aircraft gun, in german called “acht-acht” (eight-eight), not “Bertha”. Bertha is the name of the gun emplacement. The second foto shows not a gun. It is the batteries rangefinder.

Many Greetings,

Raymond

Guten tag Raymond; thank you for contacting us regarding the captions. Not being an expert on act-achts or battery rangefinders, I’m not surprised I made a mistake. I went with the provided caption. I appreciate you pointing out these errors. We have made the necessary changes. Please don’t hesitate to let me know if you see any other mistakes in future blogs. STEW