African American men and women who served in the American armed forces during World War II fought on two war fronts. The war against the Axis powers is obvious. However, their second war was fought on the home front against Jim Crow.

Our blog today highlights the extraordinary efforts of the Tuskegee Airmen, the first African American military aviators in the history of the United States Army Air Force (USAAF). We’ll also introduce you to two all-Black military divisions that fought during the first and second world wars.

MEDIEVAL PARIS – Volume One & Volume Two

Let us take you on a visit to the Paris of the Middle Ages. Come walk in the footsteps of the men, women, and children who lived, worked, and played in medieval Paris. Stop and see the only three residences still existing from medieval Paris. Learn about the scandalous Nesle Affair. Many of the stops are sites that most tourists don’t know even exist.

Did You Know?

Did you know that archeologists in England have excavated an experimental catapult system designed to launch British bomber planes? The catapult, located in Oxfordshire, England was called the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) Mark III Catapult, or Harwell RAE Mark III Catapult (the site was the former RAF Harwell base and is now the site of the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus). A prototype was built between 1938 and 1940 but never was used due to design issues. It was buried and a conventional runway was built over it.

The strategy was to eliminate taking off from a long runway thereby saving fuel and increasing a plane’s range. It had a 98-foot-wide circular pit topped by a turntable. A plane on the turntable could be aimed toward one of two concrete track runways measuring only 269 feet (compared to a 6,000-foot-long conventional runway). A tow hook and propulsion system were supposed to catapult the aircraft. Unfortunately, the catapult system did not fit the bomber planes it was “designed” to shoot into the sky. After the war, the pit was used to store radioactive material and remained buried until excavation was begun by the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA).

Although a land-based catapult was never used, it did serve as the inspiration for the aircraft catapult systems used on board naval vessels including the catapult aircraft merchant (CAM) ship.

I would like to express my gratitude to the Museum of London Archaeology for their kind permission to use the images in this blog. MOLA is a leading archaeological and built heritage practice and educational charity, providing independent services to the development and heritage sectors.

Click here to visit the web-site.

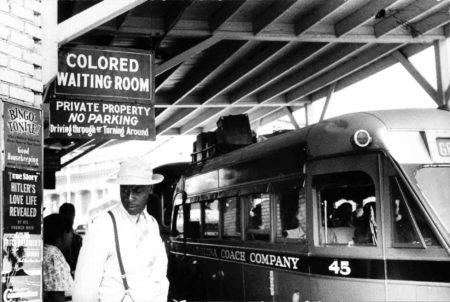

Jim Crow Laws

One of the sad chapters in American history is the period of time known for its Jim Crow Laws. These were a collection of state and local statutes that legalized racial segregation. It occurred for about one hundred years with its roots in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War and ending in the 1960s with the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 1965 Voting Rights Act, and the 1968 Fair Housing Act. Unfortunately, while Jim Crow Laws were legally banished sixty years ago, enactment of these anti-discrimination acts did not guarantee the full integration of or adherence to anti-racism laws.

Founded in Tennessee in 1865 by a group of former Confederate soldiers, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) grew into a secret society intent on terrorizing Black communities. Its members ranged from southern politicians to criminals and everything in-between. The goal of the KKK was to assert White supremacy through violent means and support discrimination and racism through the Jim Crow Laws.

Violence was one of the ugly aspects of Jim Crow. African American schools were vandalized and destroyed. Black citizens were physically attacked, tortured, and lynched during the night. Families were forced off their land. As the laws expanded across the country, segregation took hold. Public parks were off limits to Blacks and segregated restaurants became common as did segregated drinking fountains, restrooms, waiting rooms, and building entrances (among just about everything else). Even separate textbooks were required for White and Black students and even separate bibles were used to swear in people to government positions.

Jim Crow was most prevalent in America’s southern states and in particular, the United States military. Despite the bravery shown by Black soldiers during the Revolutionary War and fighting for the North in the Civil War, the African American soldier was not considered worthy enough to fight in combat. Not surprisingly, this racist attitude infiltrated West Point and the other military academies.

Jim Crow and the Military

Anticipating the European conflict would eventually threaten American security, President Roosevelt signed the Selective Training and Service Act on 16 September 1940. It was the first peacetime draft in our country’s history, and it required all males between the ages of 21 and 45 to register for military service.

Eligible African American men were expected to register for the draft. However, they were to receive “separate but equal” treatment. In 1896, the United States Supreme Court decided in Plessy v. Ferguson that state-sanctioned discrimination was permissible as long as the “separate but equal” treatment was applied. The military stretched the “separate but equal” as they assigned most African American soldiers (male and female) to service or defensive units as opposed to front-line battle assignments. Of the sixty-one thousand American soldiers that landed on Omaha and Utah Beaches on D-Day, only about 1,700 were African American.

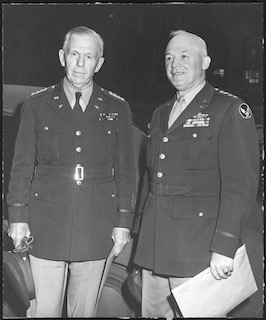

Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall (1880−1959) rejected integrating the army and announced, “… it is the policy of the War Department not to intermingle colored and white enlisted personnel in the same regimental organization.” Marshall believed it was not the responsibility of the military to experiment “which would inevitably have a highly destructive effect on morale” or at the expense of national defense.

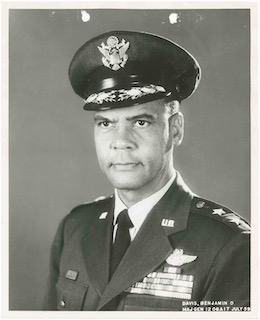

On 27 September 1940, three prominent civil rights leaders met with President Roosevelt to convince him to integrate the military. The president gave these men the impression he would move forward with integration. However, more than a week later, a press release confirmed FDR’s agreement with Gen. Marshall regarding the “separate but equal” policy. The Black community was stunned and rightfully upset. So, what does a wily politician do when a national presidential election is several weeks away and there is a need to placate Black voters? If you are FDR, you order the promotion of two prominent African American men. Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. (1877−1970) was promoted to become the first Black general in the U.S. Army (fourteen years later, his son became the first African American general in the air force) while William Hastie (1904−1976) was appointed as an assistant to Henry Stimson (1867−1950), FDR’s secretary of war.

Buffalo Soldiers and Blue Helmets

Two all-Black infantry divisions were formed during World War I and fought in both world wars. The 92nd and the 93rd Infantry Divisions were formed in 1917 and then reactivated in 1942.

The 92nd, or “Buffalo Soldiers,” was the only African American combat infantry unit during World War II. There were other all-Black units, but they served in service capacities or as support for other combat units. Commanded by Gen. Edward Almond (1892−1979), the 92nd was blamed for the division’s poor performance in combat that resulted in almost 3,000 casualties during the Italian campaign of 1944−45. Having been hand-picked by the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. George C. Marshall, Almond convinced Marshall the Buffalo Soldiers were inferior to White soldiers and only good enough for support or defensive roles. Using declassified material, historians have reevaluated the combat situation and now blame Almond, his racist attitude, and the prejudice of his officers toward the soldiers for the problems encountered during the battles. Two Buffalo Soldiers received the Medal of Honor.

The 93rd fought under the French during the first world war and acquired the nickname Casques Bleus, or “Blue Helmets” that were issued to the soldiers. During World War II, the division fought in the Pacific Theater but were primarily used for construction projects and defensive operations. Despite Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing (1860−1948) having earned his nickname as an officer in a Buffalo Soldier regiment, the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) commander refused to allow African American soldiers to serve in combat. Twenty years later, this view would later influence his one-time aid and friend, Gen. Marshall, to reject integrating the army in World War II.

The Tuskegee Airmen

In April 1939, Congress appropriated funds to train African American pilots, but only private civilian flight schools were designated to provide the training (assuming they wanted to train African Americans). The men were trained at five airfields surrounding Tuskegee University in Alabama. Three months before the formation of the USAAF (its predecessor was the U.S. Army Air Corps and its successor is the U.S. Air Force), the first all-Black unit was created ⏤ the 99th Pursuit Squadron (later renamed as the 99th Fighter Squadron). Looking back on his experience, Coleman Young, a former Tuskegee airman (and mayor of Detroit, Michigan) noted that the trainees were held to higher standards than their White counterparts. He believed it resulted in an elite group of aviators.

After the men were commissioned in the early days, they were left stranded and not given their assignments. The head of the USAAF, Henry “Hap” Arnold (1886−1950) said, “Negro pilots cannot be used in our present Air Corps units since this would result in Negro officers serving over White enlisted men creating an impossible social situation.” This is why the Tuskegee Airmen served in all-Black units.

The missions of the Tuskegee Airmen were two-fold: as combat fighters (i.e., pursuit and attack) and escorts for the medium bombers (e.g., Martin B-26 Marauder). After pilot graduation, the men were assigned to either the 332nd Fighter Group (99th, 100th, 301st, and 302nd Fighter Squadrons) or the 477th Medium Bomber Group (616th, 617th, 618th, and 619th Bombardment Squadrons). While the P-51C Mustang was the primary airplane, the airmen also flew the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, Bell P-39 Airacobra, and Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. Eventually, the tails of the P-51s were painted bright red to distinguish the Tuskegee planes from other squadrons. In time, the “red tails” became welcome sights for bomber crews flying through hostile airspace.

Throughout the war, the African American pilots experienced indignities caused by “Command difficulties.” Airbase commanders purposely segregated the bases even to the point of drawing a line in the base theater for racial seating purposes. Officer’s clubs were segregated. (One Tuskegee officer entered a “Whites Only” club and was court-martialed.) One of the biggest irritants in the beginning was watching the White officers being quickly promoted while the African American officers were not and as such, not one Tuskegee airman held a command position until later in the war.

Between 1941 and 1946, 992 African American pilots were trained. Of these, 355 were deployed overseas with 84 losing their lives. Thirty-two were captured and spent the remainder of the war in German POW camps. The Tuskegee Airmen flew a total of 1,889 missions with 112 enemy aircraft destroyed in the air and 150 on the ground. (This included three of Germany’s new Messerschmitt Me 262 fighter jets.) Rail cars, trucks, boats, and barges were destroyed by the attacking Redtails. As escorts for heavy bombers, the Tuskegee Redtails scored higher marks than other P-51 escort units. In other words, their escort record revealed a lower number of bombers lost compared to other squadrons.

Let’s Meet Some of the Airmen

The two most well-known Tuskegee officers were Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. (1912−2002) and Daniel “Chappie” James, Jr. (1920−1978).

Benjamin Davis, Jr. was the first African American general in the USAF and in 1998, he was promoted to a full general (four stars). (His father was the first Black general in the U.S. Army.) Flying sixty missions, Davis became the commander of the 99th Fighter Squadron under the 332nd Fighter Group. He graduated from West Point in 1936 but endured four years of silence from his classmates. Rejected by the US Army Air Corps (they refused to accept African Americans), Davis served in one of the Buffalo Soldier units until being accepted into the Tuskegee training program. Fifteen years after the war ended and serving in many command positions, Davis received a permanent promotion to brigadier general. His last assignment was deputy commander-in-chief of the U.S. Strike Command as well as commander in the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa.

Daniel James, Jr. was a Tuskegee instructor during World War II and flew combat missions during the Korean Conflict and Vietnam War. Training Tuskegee men in the 99th Pursuit Squadron, Chappie went on to fly a B-25 Mitchell with the 617th Bomb Squadron (477th Bomb Group). In 1970, he was promoted to brigadier general and became the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense. Five years later, James became a four-star general and the highest ranking African American in the history of the U.S. military up to that time.

Harry Stewart, Jr. (b. 1924) served as a fighter pilot in the 332nd Fighter Group. He was one of only four Tuskegee airmen to down three enemy aircraft in a single day and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Stewart is one of the last surviving members of the Tuskegee Airmen and he participated in the 2006 White House ceremony honoring the airmen with the Congressional Gold Medal.

Awards and Decorations

- Three Distinguished Unit Citations were issued ⏤ 99th Pursuit Squadron, 99th Fighter Squadron, and the 332nd Fighter Group.

- One Silver Star

- Ninety-six Distinguished Flying Crosses

- Fourteen Bronze Stars

- 744 Air Medals

- Sixty Purple Hearts

Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond, Commanding General of the 92nd Infantry Division in Italy inspecting the troops before a decoration ceremony. Photo by anonymous (c. March 1945). PD-U.S. government. Wikimedia Commons.

Post War

In 1948, President Truman desegregated the military. Immediately, the Tuskegee Airmen found themselves in high demand throughout the USAF. In 1949, qualified airmen were assigned to all-White units. During post war flying and gunnery competitions, Tuskegee pilots won major awards. Lt. James Harvey III stated, “We didn’t guess at anything. We were good.” While the Tuskegee Airmen won the respect of others, their wartime record and proven bravery did not silence everyone and unfortunately, racial harassment continued.

Previous blogs addressing African American struggles (and successes) in the military include Test of Medal: Montford Point Camp (click here to read) and The Ten Percenters (click here to read).

Next Blog: “Meyer’s Bugle”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Chafe, William H., Raymonds Gavins, and Robert Korstad (editors). Remembering Jim Crow: African Americans Talk About Life in the Segregated South. New York: The New Press, 2021.

Charles River Editors. The Tuskegee Airmen: The History and Legacy of America’s First Black Fighter Pilots in World War II. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015.

Davis, Benjamin O. Jr. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.: American: An Autobiography. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press; Illustrated edition, 2000.

Fletcher, Marvin E. America’s First Black General: Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., 1880−1970. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas (1989).

Haulman, Daniel. Eleven Myths About the Tuskegee Airmen. Montgomery, AL: NewSouth Books, 2012.

Holway, John B. Red Tails: An Oral History of the Tuskegee Airmen. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2012.

Homan, Lynn M. and Thomas Reilly. Black Knights: The Story of the Tuskegee Airmen. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2001.

Klarman, Michael J. From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Moye, J. Todd. Freedom Flyers: The Tuskegee Airmen of World War II. NY: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Percy, William A. Jim Crow and Uncle Sam: The Tuskegee Flying Units and the U.S. Army Air Forces in Europe During World War II. The Journal of Military History, 67, July 2003.

Roll, David L. George Marshall: Defender of the Republic. New York: Dutton Caliber, 2019.

Stewart Jr, Lt. Col. Harry and Philip Handleman. Soaring to Glory: A Tuskegee Airman’s Firsthand Account of World War II. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing, 2019.

Tucker, Phillip Thomas. Father of the Tuskegee Airmen, John C. Robinson. Washington D.C.: Potomac Books, 2012.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

I’d like to thank Sylvia Davis, the culture editor of online publication, Bonjour Paris, for taking a chance on my presentation skills. She graciously offered me the opportunity to present a ZOOM lecture on “Marie Antoinette’s Last Ride” to a rather large audience of Bonjour Paris members as well as non-members. It must have gone well because Sylvia has scheduled us for two more lectures in 2024.

In honor of the 80th anniversary of D-Day, my next Bonjour Paris lecture will be on Thursday, 6 June 2024. The topic will be “Operation Double Cross” (click here to read the blog, The Double Cross System). This lecture will be offered through France Today, a sister digital publication.

The second lecture will be “Creepy Cemeteries” on 30 October 2024 ⏤ just in time for Halloween. This lecture will be based on our future book, Where Did They Bury Jim Morrison, the Lizard King? A Walking Tour of Curious Paris Cemeteries.

We will keep you informed and reminded of these lectures next year.

Please check out Bonjour Paris at their website (click here) and France Today at their website (click here).

We have been a member of Bonjour Paris for many years and enjoy the many articles covering a wide array of topics including interesting but hidden sites to visit while in Paris.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

We’ve heard from many of you who attended the Bonjour Paris presentation. Thank you to everyone who took the time to contact us as well as those of you who signed up for our bi-weekly blogs. Several of you are traveling to Paris and purchased the two volumes on the French Revolution. I hope the walking tour books come in handy and add value to your visit.

Also, we were able to introduce several people to our good friend, Raphaélle Crevet. She is a licensed tour guide in Paris and its surroundings (e.g., Versailles and Château Fontainebleau). I can’t say enough good things about Raphaélle and her superb talents in conducting personal tours. Raphellecrevet@yahoo.fr

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Shepherd.com is like wandering the aisles of your favorite bookstore.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Check out Stew’s new bookshelf on the French Revolution.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross