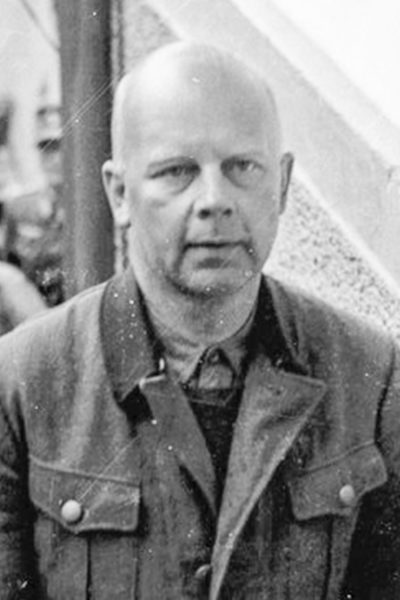

Disguised as an Austrian private, former SS-Obergruppenführer Karl Oberg (1897−1965) was captured in June 1945 by American troops. Oberg was responsible for Nazi security forces (e.g., Schutzstaffel, Gestapo, and Sicherheitsdienst) in occupied France from April 1942 until the country’s liberation in August 1944. He was directly responsible for the deportations to KZ Auschwitz II-Birkenau of more than forty thousand Jews. Originally convicted of crimes against humanity by the British and then separately by a French court in 1954, Oberg’s death sentence was commuted to life in 1958 by the French president. A year later, the life sentence was further reduced to twenty years. In 1962, President Charles de Gaulle pardoned Oberg and he was set free. An aberration of justice in a case of a former Nazi convicted of crimes against humanity? No. Unfortunately, this was not an exception but rather the norm during the early postwar years.

Did You Know?

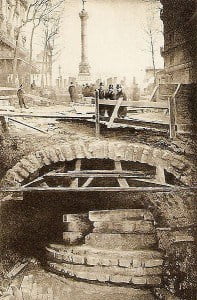

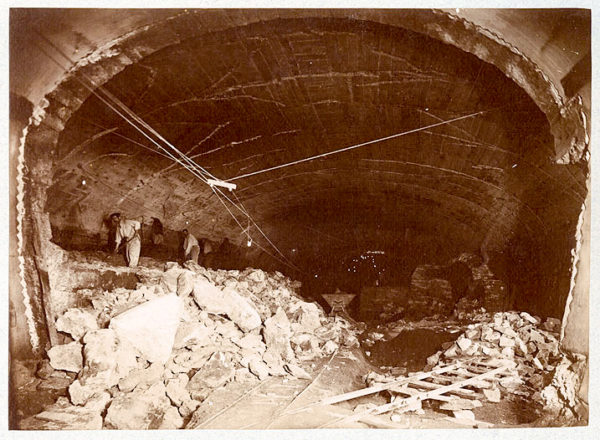

Did you know that one of my favorite Paris métro stations is the Bastille. Located at the intersection of the 4e, 11e, and 12e, it is a large station serving lines 1, 5, and 8. Most people storm the Bastille métro station in a hurry to get to their trains and don’t really take the time to study the artwork or other interesting historical artifacts on the platforms. Built on the site of the original Bastille, a revolutionary symbol of the tyrannical French monarchy, the station commemorates the storming of the fortress on 14 July 1879 that marked the start of the French Revolution. (Refer to my two-volume series, Where Did They Put the Guillotine? A Walking Tour of Revolutionary Paris.) There were only seven prisoners at the time and ironically, King Louis XVI had plans for demolishing the prison. The thousand or so angry citizens had plenty of guns but no gunpowder. They heard there was gunpowder stored inside the Bastille and after taking the fortress, they found the rumors to be false. So, they did the next best thing by forcibly taking the Bastille governor to the Hôtel de Ville (city hall) where along the way, he was stabbed to death and beheaded.

If you follow the tunnels for Line 1, you will see multi-paneled ceramic tiled murals. These were created in 1989 by various ceramic artists to commemorate the two-hundred-year anniversary of this momentous event. The murals celebrate the Age of Enlightenment (from which the city of Paris derived its name, “The City of Light”), hot-air balloons, the Third Estate (i.e., ordinary citizens), the revolution and of course, bread. Remnants of the Bastille can be seen in the tunnels of Line 5. On the platform in the direction of Bobigny-Pablo Picasso, the remains of an outer wall are visible. In 1899 during the excavations of the station, the foundations of the Liberty Tower were uncovered. The stones were dismantled and reconstructed along the Seine at the Square Henri-Galli (4e) where you can visit today. Many stones were carved into miniature versions of the Bastille and sold. One of these can be seen at the Musée Carnavalet (my favorite Paris museum). Many of the remaining stones were used to build Pont de la Concorde (the bridge connecting the Right and Left Banks off the Place de la Concorde). Due to subsequent expansions of the bridge, the only way to see the original stones is from a boat while passing underneath the bridge. Along one side of the Bassin de l’Arsenal (the former moat that supplied water to the Bastille) are some of the original fortress walls.

So, for you hard-core history buffs and in particular, French Revolution students, take the time to visit the Bastille métro station and be sure to bring along my first two books, Where Did They Put the Guillotine?

Visit our previous blog, Paris Art Nouveau, for some more stories on the Paris métro system (click here to read).

One of the questions I have repeatedly asked myself over the past years is why so many former Nazis were not held fully accountable for the heinous atrocities they committed. Sure, a handy pragmatic explanation is the Cold War forced the Allies (and Soviet Union) to recruit scientists, engineers, doctors, and spies from the German side of the war. Yet, many of these people were some of the most ruthless perpetrators of crimes against humanity. While I have tried to understand the reasoning behind those decisions, it doesn’t mean I agree with them. (While we must be careful applying judgement in hindsight, especially after so many years, the enormity of Nazi crimes outweighs any rational reasoning for past decisions to pardon or not hold former Nazis accountable.)

The situations I’m scratching my head over are the men and women who were tried, convicted of crimes, and in many cases, sentenced to death only to be released after serving minimal terms. (We can also suffer angst over the former Nazis who were never brought to justice or those whom the Allies protected.) I’ve never run across any concrete reasons why leaders such as Gen. Charles de Gaulle (or the subject of today’s blog) would spare these people. It was not fair and presented a grave injustice to the Nazis’ victims.

Who were the people who pulled the strings to pardon, commute, or outright release these criminals? They must have been very powerful people. Were they Americans, British, or French? What was their rationale? I don’t think the Soviets were that humane, so I don’t lump them into this group. (In fact, Stalin wanted them all executed.) The answer to these questions is very complex and so, I have approached this subject with a very wide brush. For a more comprehensive study, please refer to the recommended reading list below and in particular, Mary Fulbrook’s book, Reckonings.

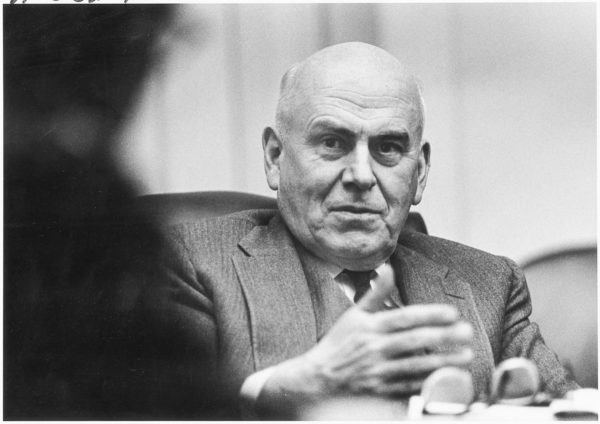

John Jay McCloy

John J. McCloy (1895−1989) was a lawyer, diplomat, banker, and advisor to nine presidents beginning with Franklin D. Roosevelt. Born in Philadelphia, McCloy dropped out of Harvard Law School in 1917 to join the army and saw action in France during the last weeks of World War I. Discharged in 1919, McCloy returned to Harvard and two years later, obtained his law degree. Working for a prestigious New York City law firm, McCloy worked on several very large cases involving Germany and German corporations (including I.G. Farben, the supplier of gas used in the concentration camps). As a result, he developed a strong interest in Germany.

In September 1940, McCloy was hired as a war planning consultant by Henry Stimson, United States Secretary of War. In April 1941, McCloy was appointed as assistant secretary of war and he became involved in the Lend Lease program, the draft, and foreign intelligence (including sabotage). McCloy became a trusted advisor to the president and top-level members of the government. During the war, McCloy served on task forces that built the Pentagon, created the Office of Strategic Services (the predecessor to the CIA), and the proposal to create the United Nations. One of his proposals was to form a war crimes tribunal. In 1942, McCloy pushed for the internment of Japanese American citizens, and he supervised the evacuations to the camps. In response to requests to bomb the rail tracks leading to Auschwitz and other extermination camps, McCloy did not support the diversion of aircraft for that purpose. (Roosevelt also rejected those proposals.) Other major events that McCloy influenced included the use of the atomic bombs on Japan (he was against it), the rejection of the Morgenthau Plan (a plan to strip Germany of its industrial base), and by late 1945, proposing the desegregation of the military forces (he had previously been an opponent of civil rights).

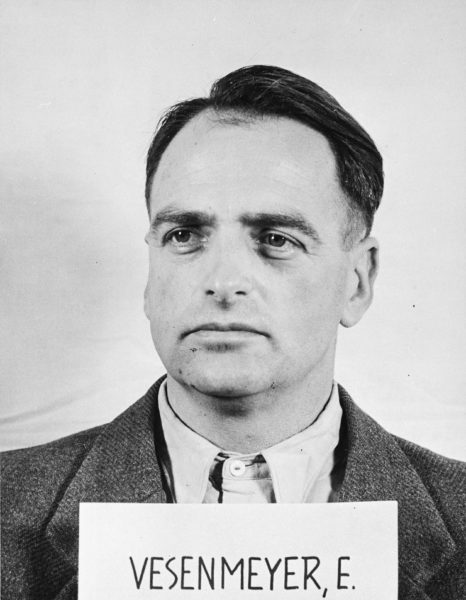

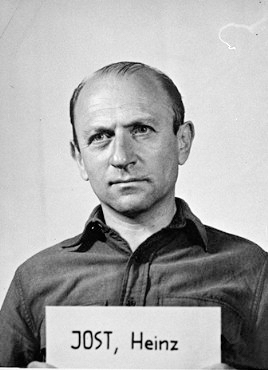

After the war, McCloy returned to private enterprise including a term as the president of the World Bank. In September 1949, McCloy was appointed the military governor for the U.S. Zone in Germany and remained in that role until August 1952. During that time, the Federal Republic of Germany was formed. German leaders convinced McCloy to approve pardons and commutation of sentences of Nazi criminals (commonly known as the 1952 Amnesty). He also approved returning property confiscated from convicted industrialists (e.g., Alfried Krupp and Friedrich Flick). One of the Nuremburg judges expressed his shock over McCloy’s actions, in particular the restitution of property that had been ordered by the military tribunal. Other convicted former Nazis pardoned or commuted included the men responsible for the Einsatzgruppe (SS mobile killing squadrons responsible for more than one million murders) and the Malmédy massacre. McCloy pardoned Edmund Veesenmayer (1904−1977) and the former Nazi served only two years (of his twenty-year sentence). Veesenmayer was a senior officer in the Schutzstaffel (SS) and worked with Adolf Eichmann to perpetuate the Holocaust. McCloy pardoned Ernst von Weizsäcker (1882−1951) who had been convicted of crimes against humanity for his role in the deportation of French Jews to KZ Auschwitz II-Birkenau. He later wrote that he had been a member of the German resistance. However, Weizsäcker was buried in his full Nazi uniform including a swastika armband. The French discovered that Klaus Barbie (“The Butcher of Lyon”) was in U.S. protective custody and requested that the former Nazi convicted in absentia of crimes against humanity be turned over to them for execution. McCloy refused and Barbie fled to Bolivia with assistance from the United States.

After his role as military governor, McCloy returned once again to private enterprise. However, he continued to serve U.S. presidents in many advisory and task forces including the Warren Commission where he was instrumental in obtaining a unanimous consensus of the “lone gunman” theory. McCloy was a Republican but was adept at working both sides of the aisle. He was a member of a small informal group that became known as “The Wisemen.”

Denazification

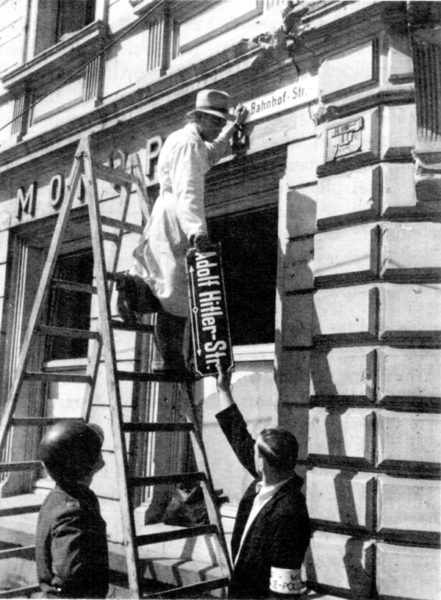

Denazification was the Allied process of expunging Nazi culture, ideology, and politics from German and Austrian society. It was also seen as a method of purging former Nazis from administrative, legal, and other key areas. Part of the process was to remove all physical symbols of the Nazi regime including the eradication of the swastika. The extent of denazification varied based on country, occupation zones within Germany, and within the new West German government. It was very unpopular with the Germans and most saw the process as a hurdle for moving on with their lives as opposed to an opportunity to confront the immediate past. Denazification was essentially an American driven program as the British were lukewarm to it and the French government never supported it. By the end of 1946 with the onset of the Cold War and recognition of West Germany’s important role in the conflict with the Soviet Union, denazification lost its steam and was finally abandoned in 1951.

About ten percent of the German population had been members of the Nazi party. However, tens of millions of Germans were involved in Nazi-related organizations such as the Hitler Youth, German Labor Front, and the League of German Women. The strongest supporters of the Nazis were the industrialists who contributed money, produced weapons, and used slave labor. Denazification was entirely disregarded by the Allies (and Soviets) when it came time to recruit scientists, doctors and engineers under “Operation Paperclip.” (Click here to read the blog, Hang ‘em or Hire ‘em.) There was virtually no denazification in the German medical professions. This meant the doctors, nurses, and enablers who had participated in programs such as Aktion T4 (euthanasia) were never held accountable for the murders of disabled children and adults. (Click here to read the blog, Hitler’s Directives.)

The process started with all Germans over the age of eighteen completing a questionnaire about their Third Reich activities and memberships. A complete list of Nazi party memberships was obtained and could be cross-checked to the questionnaires. About 1.5 million people had joined the party before 1933 and they were considered to be hard-core Nazis. Germans were classified into five categories:

| V. | Persons exonerated | No sanctions. |

| IV | Followers | Possible restrictions on travel, employment, etc. |

| III | Lesser Offenders | Probation for two to three years. |

| II | Offenders | Immediate arrest; ten-years imprisonment. |

| I | Major Offenders | Immediate arrest; imprisonment or death penalty. |

The caseloads were enormous and there were not enough people to adequately administer the denazification program. The majority of Germans pleaded they were forced to join or support the party. Many claimed they were secretly anti-Nazi and shifted the burden of guilt onto others. (“It was Hitler’s fault.”) Most of the people were ultimately classified as V, or persons exonerated. Those who rated the other classifications were rarely given or even served the punishment requirements. (A good example is the industrialist, Ernst Heinkel, who built his aircraft using forced labor. He managed to get his status downgraded to “exonerated.”) By January 1946, a report was submitted outlining the failure of the program to adequately identify the people who supported or assisted the Nazi party. Concurrent with all of this, the International Military Tribunal (IMT) was in session in Nuremberg with former senior Nazi party and military personnel on trial.

Postwar Trials

After the main IMT trial, the Americans held twelve additional trials in Nuremburg against high-ranking Nazi representatives. The first trial was the Doctors’ Trial (Case 1). The defendants were SS and camp doctors, Wehrmacht medical staff, and senior officials in the health service (click here to read the blog, The Rabbits of KZ Ravensbrück). Of the twenty-tree defendants, seven were executed. All others (life imprisonment to fifteen years) were released from jail by 1955 (the majority had been freed by 1952). The Einsatzgruppen Trial (Case 9) had twenty-two defendants in the dock. Fourteen received death sentences but only four were executed. The remainder received between ten-years and life. All were free by 1956 (the majority in 1951/52).

Other trials that specifically focused on individual concentration camps were held in the countries where the camps were located. These separate trials included Auschwitz, Dachau, Buchenwald, Mauthausen, Flossenbürg, Mühldorf, Dora-Nordhaussen, Belsen, Ravensbrück, and Neuengamme. War crime trials were held in eastern European countries and cities such as Poland and Bucharest. While many of the perpetrators in these trials received the death sentence, most had their sentences commuted to life and ultimately were pardoned and released by 1956. Individual countries dealt with their collaborative leaders, traitors, and war criminals with separate trials. Karl Oberg was tried in France along with Helmut Knochen (1910−2003), the SS officer in charge of the Sicherheitsdienst. Along with Oberg, Knochen was pardoned by de Gaulle and released in 1962.

By 1958 and regardless of sentence, all convicted and imprisoned former Nazis had been released from prison except for three prisoners in Spandau Prison: Rudolf Hess (1984−1987), Baldur von Schirach (1907−1974), and Albert Speer (1905−1981).

Postwar Accountability

Mary Fulbrook’s book, Reckonings, states that a million people are believed to have participated in the Holocaust and were directly involved with the extermination of Jews and other people the Nazis deemed unworthy. Only twenty thousand people were found guilty of crimes and less than six hundred received heavy sentences.

Between 1946 and 2005, about 140,000 people were tried in Germany (formerly West Germany and beginning in 1989, the reunited Germany) for Nazi crimes. Only 6,656 were convicted and of these, five thousand received sentences of less than two years. Only 164 individuals were sentenced for murder. (As a benchmark, Auschwitz alone employed between four and six thousand people.) Between 1945 and 1989, East Germany (controlled by the Soviet Union) produced almost thirteen thousand convictions and those convicted faced harsher sentences. However, the majority of sentences were less than three years imprisonment.

Why?

Why weren’t men and women held accountable and if they were, why were most of them released by the mid-1950s regardless of the severity of their crimes?

- The Cold War and economic importance of Germany caused the Americans and British to lose interest in denazification. They turned the process over to the Germans in early 1946. (The French never had a denazification process.)

- The West German infrastructure needed bureaucrats to run the country. For more than twenty years, about one hundred former Nazi party members held high-ranking positions within the West German Justice Ministry. Ninety out of 170 leading lawyers and judges were former Nazis. Of those, thirty-four had been members of the Sturmabteilung (SA)⏤the paramilitary thugs responsible for Kristallnacht and other acts of violence against the Jews. One lawyer had been responsible for drafting the Nazi law prohibiting marriage between Jews and non-Jews; he held a top position in the family-law section of the postwar German Justice Ministry. These high-placed men were able to protect other former Nazis from post-war justice. More than half of the employees of the “new” Interior Ministry were former members of the Nazi Interior Ministry run by Heinrich Himmler.

- The first chancellor of the new republic, Konrad Adenauer, was opposed to denazification and supported a strategy of integration (i.e., integrating former Nazis into the new republic’s civil service). Article 131 was passed in 1951 by the West German government. It reinforced the effects of Nazi stigmatization and ordered preference to the reinstatement of former Nazis at the expense of their victims.

- After turning their attention to the Cold War and threat of the Soviet Union, western countries lost interest in pursuing Nazi criminals.

- By 1949, Germany and its citizens did not view membership in the Nazi party as “a bad thing.” Many believed the Nuremberg trials to be “victor’s justice.” Up until about thirty years ago, only a handful of Holocaust perpetrators were blamed for Germany’s defeat and Nazi atrocities. The broad system of complicity was not addressed. A strong sense of denial prevailed, and the hiring of ex-Nazis was tolerated regardless of their role in the Third Reich.

- German judges required a high burden of proof resulting in very low rates of conviction.

- For decades after the war, most of the victims of the Third Reich did not speak about their experiences (publicly or privately). It wasn’t until the trial of Adolf Eichmann in the early 1960s that a reawakening of Nazi atrocities occurred, and the Holocaust began to be talked about in public. A revived sense of interest began to percolate resulting in renewed efforts to bring Nazi perpetrators to account for their actions during the war.

These are just some of the reasons for why justice was not served. Why did Charles de Gaulle pardon or commute the sentences of men who occupied France and were responsible for the deportations of Jews, Communists, and homosexuals, along with the executions of tens of thousands of hostages, resistance fighters, and foreign agents? I don’t know the answer to that question.

One Last Example

The German general and chief of staff of the Army High Command, Franz Halder (1884−1972), was never brought to justice to face war crimes or crimes against humanity despite his direct involvement with atrocities committed by the Wehrmacht. He was hired as a consultant by the U.S. to supervise the writing of wartime memoirs of seven hundred former Nazi officers. He instructed them to delete any material detrimental to the image of the Wehrmacht. They were to portray World War II as a “noble” war and deny any war crimes. The U.S. allowed this to happen because this group was providing valuable information on the Soviets. Halder was instrumental in propagating the myth that the Wehrmacht did not participate in the type of crimes committed by the German security forces (i.e., Schutzstaffel).

Closing Statements

I will be the first to line up and argue that passing judgement in hindsight can be dangerous and, in many cases, unfair. However, considering the enormous scale of mass murder perpetrated by the Nazi regime, it is hard to comprehend how so many people responsible for these crimes escaped with little or no consequence to their actions. It’s also hard to understand why people like McCloy, de Gaulle, and Eisenhower allowed this to happen.

Men like John McCloy, considered to be “Wisemen,” really weren’t so wise after all.

★ Learn More About John J. McCloy ★

Betz, Dr. Astrid, Dr. Alexander Schmidt, Hans-Christian Täubrich. Translated by Ulrike Seeberger and Jane Britten. Memorium Nuremberg Trials: The Exhibition. Nürnberg: Museen der Stadt Nürnberg, 2012.

Fulbrook, Mary. Reckonings: Legacies of Nazi Persecution and the Quest for Justice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Schwartz, Thomas Alan. America’s Germany: John J. McCloy and the Federal Republic of Germany. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1960.

Ovenden, Mark. Paris Underground: The Maps, Stations, and Design of the Métro. New York: Penguin Books, 2008.

Our topic today is very complex. There is no simple answer to my question of why so many of these men and women escaped justice. Mary Fulbrook’s book is a very comprehensive study concerning this question. She admits time and again that the answer or answers are complicated. Ms. Fulbrook concedes her book only begins to address the issues surrounding the mystery of the pardons, commutations, release, and in many situations, the outright dodging of being held responsible. Perhaps there are historical documents waiting to be discovered that could shed some concrete information that might address some unanswered questions.

In no way can this blog begin to address the multitude of issues and if you have the same questions about postwar justice that I do, I suggest you read Ms. Fulbrook’s book.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

We are working with Roy to “redesign” the first volume now that the decision has been made to split the series into three volumes. Raphaëlle has been to Saint-Germain-en-Laye to scope out the new site we will include in the first volume. We appreciate everyone’s patience.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Alexandra B. for contacting us concerning the blog, The Wrens (click here to read). She is a researcher for a London-based production company. They are doing a documentary on the story of the Wrens and Alexandra needed an introduction to the families of the women who participated in the U-boat war games. Unfortunately, I was not able to assist her.

Rosemarie F. wrote us about the blog, The Rasputin of the Abwehr (click here to read). She mentioned a 2019 movie, A Call to Spy, that she had recently seen. It is about three SOE female agents during the war (Virginia Hall, Noor Inayat Khan, and Vera Atkins). Robert Alesch was portrayed by Joe Doyle. I haven’t seen the movie, but the reviews were generally very good, and it seems Rosemarie gave it a two thumbs-up rating. I’ll be sure to get it.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2021 Stew Ross

Hello Stu,

It is said that you are supposed to learn something everyday and today I did.

As you know I was born and raised in France during the war.

My family was pro De Gaulle 100% and that’s why I was shocked to learn about his decision (s) to let go of some of the Nazis that had committed high crimes in France.

I wonder if the French knew about it. I have never heard anyone mention these facts. Actually, now I that think about it, my brother told me one day that De Gaulle was not so clean and that he made a lot of questionable decisions. Maybe that is what he was referring to ?

I am glad I read the blog this morning as I did learn something new however sad and shocking.

McCloy and company were a disgrace in my opinion.

Like you said “we will never know why De Gaulle made such decisions”. If my parents were still with us , they would be shocked and saddened. Thanks for bringing these facts to our attention.

Hi Nicole; I was hoping to hear from you regarding our topic today. I always enjoy hearing your first-hand stories that connect with the topics of our blogs. Your comment, “sad and shocking” is very appropriate. It is very frustrating learning more and more about how these people were not held accountable. I hope some day that declassified documents will shed some light on why those decisions were made. Nicole, one of these years we will be able to travel overseas again. I’m looking forward to seeing you in Paris when that time comes. Best – STEW

John J. McCloy ll has been celebrated as one of the “wise men” responsible for steering the US through the cold war. However, despite receiving many acolades he is responsible for causing the release of an extraordinary number of Nazi war criminals and Holocaust perpetrators under the pretext of improving post war german US relations. Frankly, his wanton disregard of all principals of accountabilty and justice are, I submit, a war crime and an insult to all of the victims of the collective Nazi state.

Hi Mitch; Thanks for your comments. I agree with you one hundred percent. One of the reasons I wrote the blog was to make people aware of McCloy and his role in releasing so many war criminals. Obviously there are many other reasons why these people never fully paid for their crimes but that would be a book unto itself. Thanks again and I hope you enjoy our future bi-weekly blog topics. STEW

hi there , there seems to be an error on the page and no information around Dr Ernst Heinkel

Hi Jarrod. Thanks for contacting us. I always welcome comments from our readers regarding errors. Could you be more specific about the error? I purposely did not include additional information on Heinkel as it would have expanded the blog content and I try and keep them to a certain content size. Look forward to hearing from you about the “error.” STEW