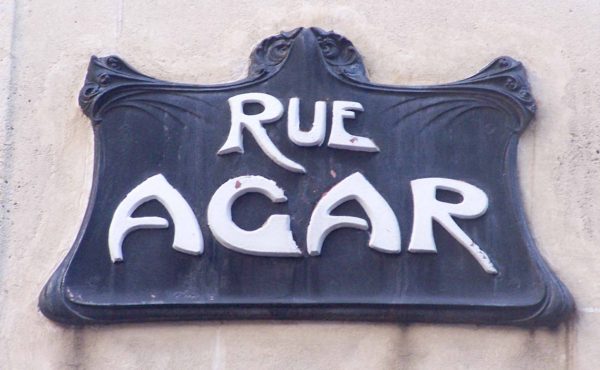

Everyone who travels returns home with certain images imbedded in their memories. One of the images of Paris that I have always retained is the decorative entrances to the métro stations. No, not every bulky, uninspired, or “run-of-the-mill” station but rather, those métro entrances that exhibit the iconic flamboyant signage designed in the style of Art Nouveau.

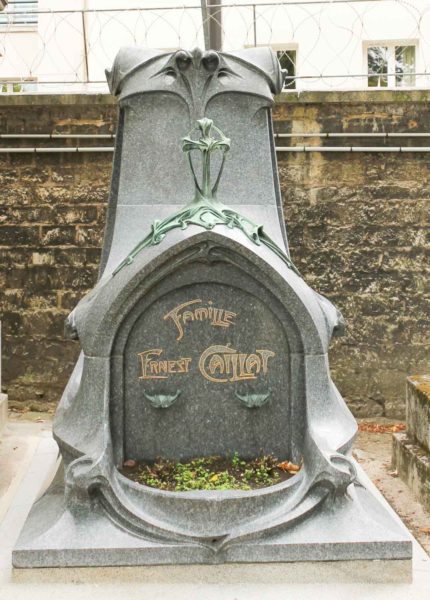

What is “Art Nouveau?” Art Nouveau, or “New Art” was an art movement that began around 1890 and ended in 1910. The movement was international (in England, it was known as “Modern Style”) and exhibited a style inspired by flowers and plants. There is a lot of movement with asymmetrical but sinuous and elegant lines. Materials used included glass, iron, and ceramics. By the end of World War I, Art Nouveau had disappeared and was replaced by Art Deco followed by Modernism.

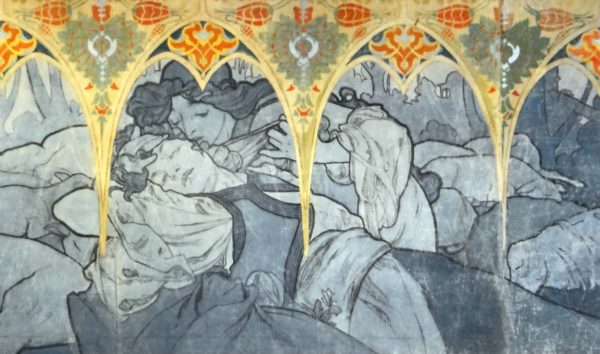

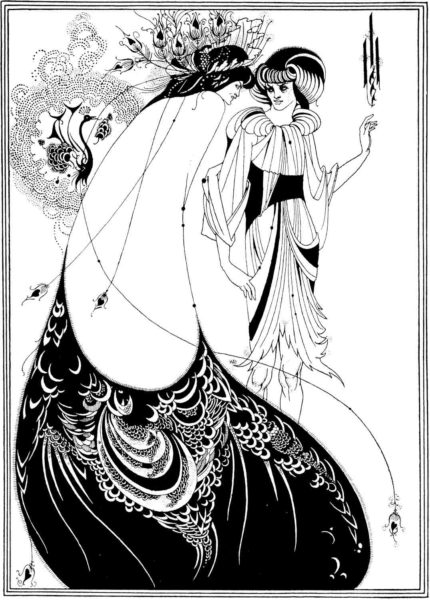

Art Nouveau was influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement (originating in Great Britain) and the first Art Nouveau architecture and interior design appeared in Brussels in 1890. It was quickly adopted by Hector Guimard in Paris. Artists such as Guimard, Alphonse Mucha, Aubrey Beardsley, and Louis Comfort Tiffany were leading proponents of Art Nouveau in architecture, jewelry, posters, graphic arts, and furniture. Mucha rejected the terminology of Art Nouveau. He said, “Art is eternal, it cannot be new.” However, the Paris art world quickly termed Art Nouveau as “le style Mucha,” or Mucha Style.

Guimard was the first to embrace Art Nouveau in Paris when he agreed to design the first generation of entrances to underground stations of the new Paris métro system at the turn of the century.

Click here to watch the video Art Nouveau vs. Art Deco.

Did You Know?

Did you know that the oldest living U.S. Marine recently passed away at the age of 107? Dorothy Schmidt Cole (1913−2021) tried to enlist in the U.S. Navy shortly after Pearl Harbor but was rejected because at four feet, eleven inches, Dotty was considered too short. So, she signed up with the United States Marine Corps. She completed her six-week boot camp training at Camp Lejeune as part of the Women’s Reserve’s First Battalion (click here to read the blog, The Medal Trap: Montford Point Camp). Dotty had learned to fly and was disappointed when her first assignment was behind a typewriter in Quantico churning out correspondence for officers. After the war, Sgt. Schmidt married Wiley Cole, a U.S. Navy sailor who had served aboard the USS Hornet in the Pacific Theater. After the war, Dotty moved to San Francisco to be with Wiley and they had their only child, Beth, in 1953. Sadly, Wiley passed away in 1955 and Dotty never remarried. Her post-war career was spent in Silicon Valley before moving to North Carolina in 1979 to be near her daughter, grandchildren, and the great grandchildren.

Semper Fidelis.

Hector Guimard

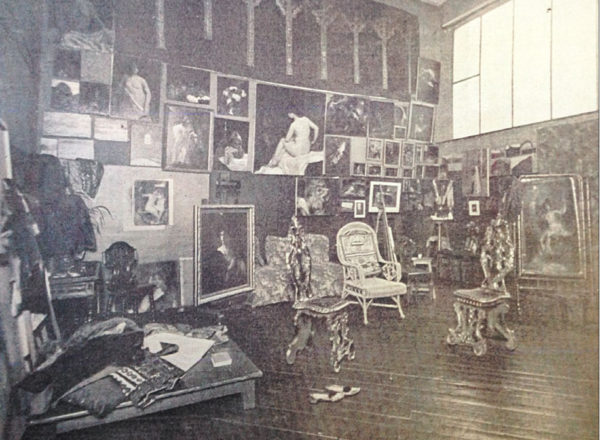

Hector Guimard (1867−1942) was a French architect, designer, and one of the leaders of the Art Nouveau movement. Guimard attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts where he studied architecture. He began to receive recognition for his architectural designs but did not have the same success with his paintings. In the summer of 1895, Guimard traveled to Brussels where he met Victor Horta (1861−1947), a founder of the Art Nouveau movement. Guimard saw one of the earliest Art Nouveau houses, Hôtel Tassel, designed by Horta. Returning to Paris, Guimard was chosen to design métro entrances, the Pavilion of Electricity, and a restaurant⏤all as part of the Paris Exposition of 1900. During this time, Guimard survived on his salary as a teacher at the Ecole nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs, or the School of Decorative Arts.

Guimard’s first major (and recognized) accomplishment was the design and construction of the Castel Béranger in Paris in 1895 (14, rue Jean de la Fontaine−16e). It is a thirty-six-unit apartment building. He persuaded the owner to let him design it in the fashion of Art Nouveau. Using this building to market his work, Guimard embarked on a very successful career as an architect. Soon, Guimard was accepting commissions for designing large maisons in French cities such as Lille, Garches, and Sèvres. All were built in the style of Art Nouveau. Several years later, Guimard was back in Paris participating in the construction of the new underground transit system.

By 1910, Art Nouveau had died out. Four years later, World War I began and Guimard moved out of Paris. Recognizing there would be a need for affordable housing after the war, he began to design standardized housing. The Paris Exposition of Decorative and Modern Arts in 1925 introduced the Art Deco movement and Guimard embraced the new style while incorporating some of the Art Nouveau elements.

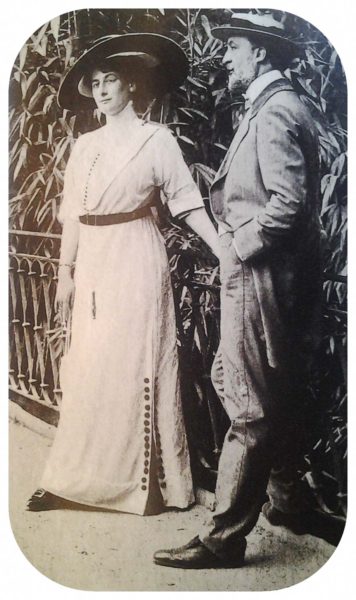

Guimard married an American painter, Adeline Oppenheim, in 1909. He built a luxury home for her at 122, avenue Mozart (16e) and it became known as Hôtel Guimard. It was constructed on a triangular plot and designed in Art Nouveau style. Adeline was Jewish and by the late 1930s, they recognized the threat of Hitler and the Nazis. In 1938, the couple moved to New York City where Guilmard died in May 1942 in a hotel on Fifth Avenue. After the war, his widow returned to Paris where she unsuccessfully tried to convince the French government to create a museum honoring her late husband. Adeline then offered Guilmard’s furniture, hundreds of his designs, and photographs to various museums.

Paris Métro Stations

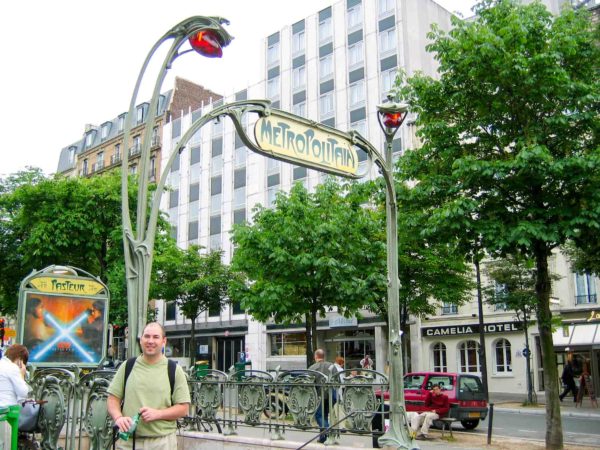

Between 1900 and 1913, Guimard designed the entrances to the first Paris Métropolitain, or métro stations in the style of Art Nouveau. It became known as style Métro, or Métro style. As with most new things (e.g., the Eiffel Tower), the elaborate entrances did not go over very well with the public or the so-called authorities on what art should look like. (The Paris artistic community loved the designs.) The Exposition Universelle of 1900, or Paris Exposition of 1900 was opened in April and Guimard’s first assignment was to design the entrances for métro stations that served the Exposition. Two of his original édicules, or entrance coverings have been preserved: métro stations Abbesses (18e) and Porte Dauphine (16e). Click here to watch the video Hector Guimard Entrance Gates to Paris Métropolitain.

A contest was held to determine the best design for above ground métro entrance structures (i.e., the trains operated below ground). The public did not want heavy industrialized type entrances. Rather, they preferred a lot of light, glass, and ceramic. This did not fit in with most of the submissions which featured bulky designs. It was Guimard’s Art Nouveau designs that best matched the expectations and he won the design contest. (It didn’t hurt that Adrien Bénard who was financing the construction of the entrances liked Art Nouveau.) Entrances to the stations with elevated platforms were awarded to another architect.

Rather than using stone, Guimard’s structural material was iron embedded in concrete. He believed this would better support the heavy glass and sinuous forms. He used “German green” colored paint because it mimicked weathered brass (or so he thought). Guimard tried to use standard components to keep the cost down as well as maintain a standard theme. The sinuous designs have been referred to as “whiplash” lines. The stylized letters used by Guimard were hand-written.

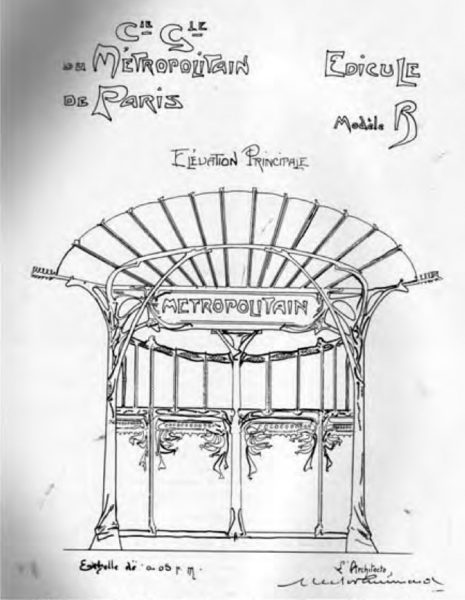

There were four basic styles of entrances: édicule design styles A, B, C and the entourage, or basic design.

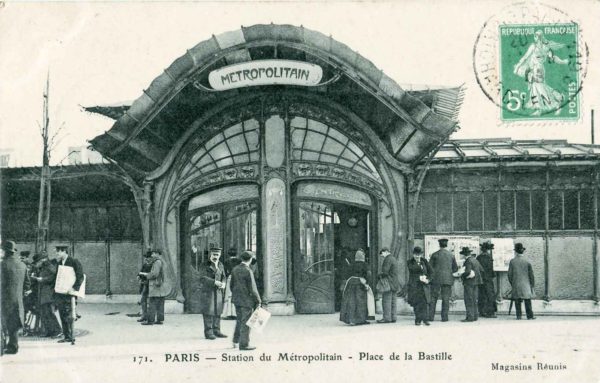

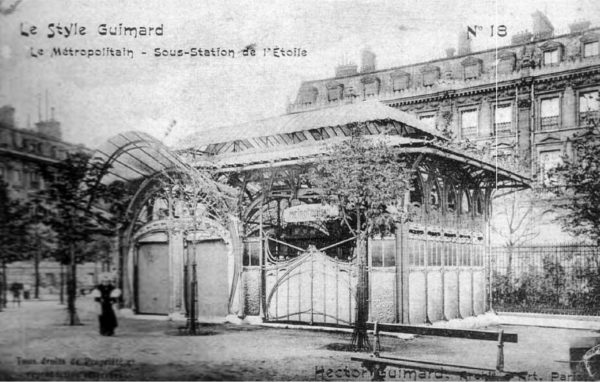

Style C: There were three self-standing buildings, or pavilions built as entrances and it was said they looked like Japanese pagodas. Each building had a waiting room. One was located at place de la Bastille while the other two were on avenue de Wagram at the Etoile station near the Arc de Triomphe. Sadly, all three were demolished (Bastille in the early 1960s and the other two prior to that).

Style B: These entrances were not free-standing buildings; they had three sides or “legs” and were “shelters” covering the entrance stairways. They were highly decorated with enamel panels and the roof was topped with frosted glass sheets that fanned outward in front. The public likened this design to a dragonfly. Again, all were destroyed except for Porte Dauphine (at its original location), Porte Maillot, Porte de Vincennes, Argentine, and Nation.

Style A: The entrances were similar to Style B except they did not use as much glass as Style B. This design was used for what were considered to be “secondary” métro stations. These included Abbesses⏤removed in 1974 from the Hôtel de Ville, or City Hall station (I’m sure the politicians weren’t very happy when they learned that their office building was considered a secondary stop), Saint-Paul, and Reuilly-Diderot.

Basic: These accounted for more than one hundred métro entrances. These are likely the designs that most people remember. They were simple (but ornate) with a very simple handrail design known as entourage. With the exception of Gare de Lyon, these station entrances did not have roofs. The original stylized “M” design was earmarked for the basic station entrance. Two lamps were incorporated in the design. They were on either side of the elongated sign over the entrance and supported by what people considered to be representations of lilies. The lamps were a reddish orange (or the other way around depending on one’s color perspective) and some thought they looked like a dragon or Devil’s eyes. This entrance design was called nouille, or noodle style.

Guimard designed and built 154 entrances and the majority of them were the basic, or entourage style. As previously mentioned, the sign (“Métropolitain” or “Métro”) spanned the entrance and was supported by the curved risers in the shape of sinuous stalks. At the top of the stalks were the lamp globes.

By 1904, discontent with Guimard’s stylized designs began to surface. The Opera station was the first to be targeted. The complaint was that the design did not fit the style of the Palais Garnier opera house. The architect Garnier stood by Guimard’s design by saying, “Should we harmonize the station at Père Lachaise (cemetery) by constructing an entrance in the form of a tomb?” Neverthless, Guimard’s entrance was torn down and replaced with a more “classical” design (i.e., stone and bulky).

Ninety-one of Guimard’s entrances survived into the 1970s. Today, eighty-six are still standing (predominately, the entourage style) and all are protected as historical monuments. Paris traded some of the original entrances to countries and cities in exchange for artwork. You can see Guimard entrances in Lisbon (Picoas station), Moscow (Kievskaya station), National Gallery of Art (in the sculpture garden), and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City (it is the original Raspail métro station entrance).

★ ★ ★ Learn More About Paris Art Nouveau and the Métro ★ ★ ★

McAuliffe, Mary. Dawn of the Belle Epoque. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2011.

McAuliffe, Mary. Twilight of the Belle Epoque. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2014.

Ovenden, Mark. Paris Underground: The Maps, Stations, and Design of the Métro. London: Penguin Books, 2009.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

The “final” manuscript of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? is now with our book designer, Roy. After he works his design and artistic magic, we review the galley and then it’s off to the printer. The next stage is getting the book into your hands. I suspect we will have the book ready for you by the end of March or early April. There are five walks (the previous books have four walks), a lot of information, and more images than in the past. I’m confident that for those people with an interest in World War II and in particular, the Nazi occupation of Paris, this new book will meet their expectations.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let all of your history buff friends and family members know about our blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank one of our readers for contacting us in regard to our 2018 blogs, Hitler’s Blood Judge and The Nazi Guillotine. He is an amateur (and respected) historian and studies “Germanic executionary traditions.” Sounds bloody, doesn’t it? You can count on a guest blog in the near future. If you have any specific topics you would like him to cover in the guest blog, please contact me at stew.ross@yooperpublications.com.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2021 Stew Ross