Each year since 1927, TIME Magazine names its “Man of the Year” (now called “Person of the Year”). Individual women have been named five times (e.g., Wallis Simpson, Soong Mei-ling, Queen Elizabeth II, Corazon Aquino, and Angela Merkel), thirteen groups have been named (e.g., “U.S. Scientists,” “American Women,” and “The Whistleblowers”), an inanimate object once (the computer), and in several instances, very controversial selections were made (e.g., Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin). The editorial board uses the following criteria for making its decision: the selection must profile a person, group, an idea, or an object that “for better or worse . . . has done the most to influence the events of the year.”

Although some of their selections ultimately met their end by assassination (e.g., Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Gandhi, and Anwar Sadat), I’m not aware of anyone who was executed. That is, except for Pierre Laval the 1931 ”Man of the Year”.

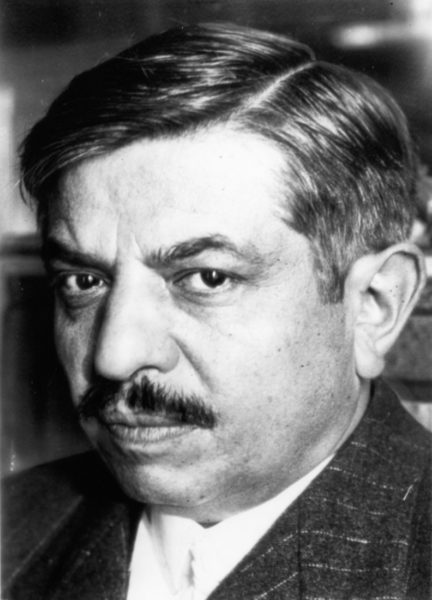

On the morning of his scheduled execution at Fresnes Prison south of Paris, Pierre Laval (1883−15 October 1945) laid down on his prison cot, pulled the sheets over his head, and bit down on a cyanide capsule. The poison was too old to finish him off. The doctors pumped his stomach along with other efforts to keep him alive. Charles de Gaulle declared that Laval would have to be shot while laying on a stretcher but his orders were refused because French code would not allow it. Laval had to be standing on his own in order to be executed by a firing squad. By 11:30 A.M., Laval regained consciousness and the process began. After being dressed, he was escorted to the police car which drove him to the execution site. Tied to the stake but not blindfolded, Laval stood straight. His body was deposited in a graveyard reserved for disgraced individuals. Eventually, his family was allowed to remove his remains and bury him at Montparnasse Cemetery (we will visit his grave in my future book Where Did They Bury Jim Morrison, the Lizard King? A Walking Tour of Curious Paris Cemeteries.

Let’s Meet Pierre Laval

Laval was born in the Auvergne region of France and never forgot his roots in the working-class region or as mayor of Aubervilliers, a north-eastern Paris suburb. By 1914, Laval had entered politics as an elected extreme left-wing deputy from Aubervilliers. Nine years later, he was elected mayor of Aubervilliers and did not relinquish that role until shortly before his arrest in 1944 by the Nazis.

Between 1914 and 1940, Laval would hold dozens of political jobs. He was a cunning politician (the polite word might be “pragmatic”) who over time, moved across the political spectrum as an extreme leftist to the far right serving under a diverse number of presidents and premiers. Despite supporting the Russian Revolution, Laval never distinguished between the ideologies of Communism and Socialism (his party split into the two factions in 1920). Along the way through ambition and greed, Laval became a multi-millionaire.

Laval married Marguerite Claussat (1888−1959) from his native village. His marriage (and family) was marked by devotion, harmony, and simplicity—the exact opposite of his political career. Their only child, Josée, married René de Chambrun (1906−2002). Her husband was the great-great-grandson of Lafayette and the nephew of Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter. De Chambrun would act as Laval’s legal counsel in addition to being Coco Chanel’s attorney. He was chairman of Baccarat, the crystal company, for more than thirty years. De Chambrun was given an honorary U.S. citizenship but this was ultimately questioned—although never revoked—in the midst of war due to his relationship with Laval (and the Germans).

Marguerite Claussat was never active in her husband’s political career. During the 1930s, it was Josée who accompanied her father on his political trips. Josée and René remained close to the Nazis during the Occupation when they would frequently attend events held at the German Embassy in Paris. After the war (and the execution), both would be Laval’s strongest supporters arguing his innocence. Josée actually got General Dwight Eisenhower to alter his war-time memoirs because she didn’t like the way he described her father. Learn more about Pierre Laval.

The Third Republic

Except for the four years of the Occupation, Laval’s political career was centered in the latter half of The Third Republic. So, I thought a brief discussion of this era might be helpful. The Third Republic was formed after 1870 to be the government of France. It was structured with a Chamber of Deputies and a Senate (the legislative branch) and a President of the Council. Initially, The Third Republic struggled with the idea of returning the country to a monarchy. However, by 1883, any support for the restoration of the monarchy had died out.

The Third Republic was defined by France’s period of colonization, polarized political parties, secularization of the government and education, corruption, scandals, anti-Semitism (displayed by the Dreyfus Affair), the Belle Époch era, and having to move from crisis-to-crisis. It was also this government and its foreign policy that were blamed for France’s entrance into World War I. Throughout its seventy-year existence, The Third Republic was very unpopular. It was dissolved on 10 June 1940 when Marshal Philippe Pétain (1856−1951) was given full powers and the Vichy government was formed to act as the legitimate French government under the Nazi Occupation of France.

Pre-War Career

There really isn’t enough time or paper to describe Laval’s pre-war career and his many positions within The Third Republic. The period between the two world wars in France was marked by ever-changing political landscapes and instability with multiple governments, presidents, and ministers. It’s no wonder that Laval held so many different positions between 1914 and 1940—he successfully changed his political stripes whenever it suited him and supported politicians who would promote and protect him. His financial investments in newspapers—backed by French banks—didn’t hurt his career either.

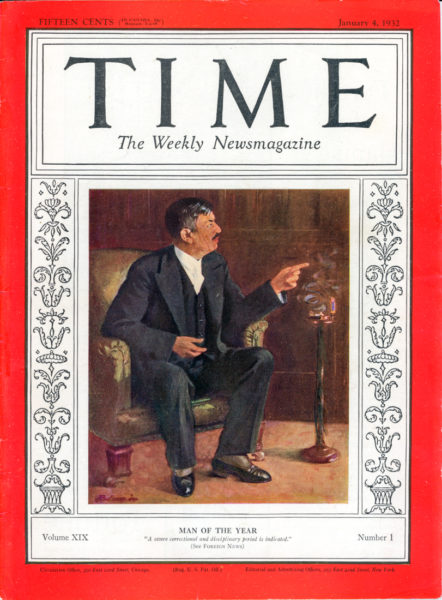

Laval was President of the Council twice before Vichy was formed: 1931 to 1932 and 1935 to 1936. He undertook a world tour in late 1931 and met with representatives of the U.S., London, and Berlin. Laval’s meeting with President Herbert Hoover would elevate his profile with both the Americans and the French. It was this trip that influenced TIME Magazine and its editors to name him as “Man of the Year” on 4 January 1932. The economic depression had not yet affected France but it soon would catch up to them albeit on a far less damaging basis than America experienced.

By the time of Laval’s second term as president, he had positioned himself as an opponent to Germany. Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933 and immediately began to dismantle the Weimar Republic in favor of his Nazi party. Within six years, Hitler abandoned the World War I reparations program, began the annexation of contingent territories, and resumed the rearmament of Germany. Before being forced to resign in early 1936, Laval had signed a treaty with Italy as well as one with the Soviet Union. It was his intent to keep these two countries from aligning themselves with Hitler.

World War II And Vichy

One of the legacies of The Third Republic was its right-wing political faction. The public face of this ideology was the organization Action Française founded by the virulent writer, Charles Maurras. Their political positions were nationalistic, anti-Semitic, monarchist, pro-Catholic, fascist, and reactionary in every way. While the party lost favor after the Catholic Church condemned it, Action Française and many of its members would re-surface within the Vichy government in leadership roles. It laid the foundation for French collaboration during the Occupation. Many of the collaborationist writers, intellectuals, and anti-Semitics found their inspiration from Maurras and Action Française. While there is no evidence that Laval supported Action Française or its platform, he was publically supporting Germany and fascism by mid-1940.

Immediately after having the new government turned over to him, Marshal Pétain named his cabinet with Pierre Laval as the Minister of Foreign Policy. It was a role Laval coveted since it would put him close to the Germans who he was convinced would win the war (as did many of his fellow citizens at that time). Pétain did not particularly like Laval (Laval blew cigarette smoke in the Marshal’s face) and there was internal opposition to him serving in the cabinet. Laval made single handed decisions to hand over copper mines and gold reserves to the Germans. Pétain removed Laval from the cabinet and had him arrested before the end of 1940. However, Pétain was forced by Hitler to bring Laval back in 1942 and he served as President of the Council, Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Interior, and Information until 1944 when the Nazis arrested Laval and detained Vichy officials.

Collaboration

Before returning to power in 1942, Laval supported French collaborationist organizations such as the Légion des Volontaires Français, a fascist militia. Shortly after re-joining Vichy, Laval gave a speech in which he expressed his “desire to establish normal and trusting relations with Germany and Italy.” He also spoke about “wishing for a German victory.”

Right about this time, Germany needed more laborers and Laval agreed to a plan to provide three French workers in return for the release of one French POW (Germany was holding between one and two million French soldiers as prisoners). His agreement was in direct opposition to the terms of the French/German Armistice which prohibited using forced French labor.

The infamous La Grande Rafle (aka Vel’ d’Hiv Roundup) occurred under Laval’s watch. Over a two-day period in July 1942, the French police in Paris arrested and detained more than thirteen thousand men, women, and children. This was in direct response to the Nazi order to begin the mass deportation of Jews to concentration camps. The Nazi order specifically said that children under the age of sixteen were exempt. However, Laval gave the orders to include all children regardless of their age. Approximately four thousand children from this roundup died at Auschwitz.

Pierre Laval became the leader of the notorious French paramilitary organization called the Milice français (aka Milice). The French Resistance considered the Milice to be more dangerous than the Gestapo. Members of the Milice were French and as such, spoke perfect French, knew the country and its culture, and could infiltrate resistance networks easier than the Germans. Their primary responsibility was to roundup Jews and résistants for deportation. They became increasingly active in hunting down and executing members of the Maquis—bands of guerilla fighters specializing in sabotage against the Germans. The brutality of the Milice matched or exceeded the Gestapo tactics.

As Minister of the Interior, Laval was ultimately responsible for the actions of the French police. He appointed Réne Bousquet as General Secretary of the Vichy Police. Bousquet was one of the officials directly responsible for the roundups of the Jews in Paris and other French cities with their ultimate deportation to the concentration and labor camps. He worked directly with General Karl Oberg, the head of the Gestapo in France as the fist of the Nazis tightened around France’s throat.

Post Normandy Invasion and Liberation

Laval’s speech to the nation immediately after D-Day implored the French not to fight. He called the résistants “enemies of our country.” By August 1944, Laval had been arrested by the Germans and in early September, the remaining members of the Vichy government were relocated to the Hohenzollern family’s castle in Sigmaringen, Germany.

Laval was able to reach Spain in the spring of 1945 but three months later, Charles de Gaulle was successful in getting the Spanish government to expel Laval. He and his wife flew to Austria where they were immediately arrested and turned over to the Free French. They were imprisoned in Fresnes Prison but Mrs. Laval was ultimately released.

Marshal Pétain, at the age of 89, went on trial first with Laval as one of the witnesses. Convicted of treason, Pétain faced the death penalty but the sentence was commuted to life by de Gaulle. Pétain was stripped of all military honors and medals except for the title of “Marshal of France” (legally, this could not be taken away). Five years later, the “Lion of Verdun” died in captivity and was buried near the prison.

Pierre Laval’s Trial

Laval’s trial began on the afternoon of 4 October 1945 and lasted until 8 October when the next day the jury went into deliberations. The verdict of guilty with a sentence of death was reached quickly.

The trial was a sham. Despite what one thinks of Pierre Laval and whether he was a collaborationist, traitor, or mass murderer, no one could mistake his trial as one that resembled any modern day due process of law. The verdict was a foregone conclusion. It became so bad that Laval made the decision not to attend the remainder of his trial or further defend himself.

His brief attempt to present a defense during the first days of the trial was to portray himself as a savior of the French. In his view, he had to collaborate with the Nazis or else the consequences for France and its citizens would have been much harsher. As history points out, Laval’s decisions in many situations actually called for greater measures or quotas than the Nazis demanded; going so far as to implement policies in the absence of any Nazi decrees. Learn more about the trial.

Epilogue

I believe that had World War II and the Nazi Occupation of France not occurred, Pierre Laval might have gone down in history as one of its greatest French politicians. Unfortunately for many innocent (and not-so-innocent) victims, history marched down a different path after which Laval along with some of his former Vichy colleagues marched down the path to face the firing squad as traitors to France.

Laval’s grave is usually never void of flowers. Unfortunately, the families of the victims of his decisions will never know the location of their relatives’ graves, let alone be able to place flowers.

Recommended Reading

If you’d like to dig a little deeper into the history of Pierre Laval, the Vichy government, The Third Republic, and Laval’s trial, I recommend the following books:

Paxton, Robert O., Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order 1944−1944. New York: Columbia University Press, 1972.

Brody, J. Kenneth. The Trial of Pierre Laval: Defining Treason, Collaboration and Patriotism in World War II France. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2010.

Shirer, William L. The Collapse of the Third Republic. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1969.

Luce, Henry−Editor. TIME The Weekly Magazine. January 4, 1932, Number One, Page 12.

Robert Paxton’s book Vichy France was considered a ground-breaking book when published in 1972. It is an exposé of France’s collaboration role with the Nazis during the Occupation. It pushed the country and its politicians into uncomfortable but serious discussions about the extent of its involvement. On 16 July 1995, reversing previous administrations’ refusals to apologize, President Jacques Chirac acknowledged the French State’s role in the persecution of French Jews and others during the Occupation. Ken Brody’s book The Trial of Pierre Laval exposes the kangaroo court scene that was Laval’s trial. Regardless of your position on Laval’s innocence or guilt and if you truly believe in a fair process of a justice system, you’ll walk away wondering why they even pretended to have his trial. William Shirer’s 1969 tome The Collapse of the Third Republic argued The Third Republic was morally weak and its leaders were cowards. He described Pierre Laval as a “crooked crypto-fascist.”

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

As you read this blog, Sandy and I are beginning our second week in Paris. Today and tomorrow mark the Journées du Patrimoine or European Heritage Days. Learn more.

It is the one time during the year when European governments choose which cultural or historical events to highlight. In Paris, the government opens “closed to the public” sites (typically government buildings), offers behind the scene tours, and free entrance to other public attractions/sites.

This weekend, there are more than sixty sites available for the public to visit. These include Palais Luxembourg, the Musée de la Légion d’Honneur, and the Palais Bourbon, site of the National Assembly.

Today, we will be visiting many sites with our friend Raphaelle. The two at the top of our list are Hôtel Beauharnais (the former German Embassy during the Occupation) and the Ministry of the Interior (site of the former Gestapo headquarters).

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2017 Stew Ross