I briefly introduced you to Suzanne Spaak in March (The French Anne Frank; click here to read). She and Hélène Berr worked together to save the lives of hundreds of Jewish children. Like most of the résistants during the Occupation, Suzanne and Hélène did what they thought was the right thing to do. As Suzanne told people, “Something must be done.”

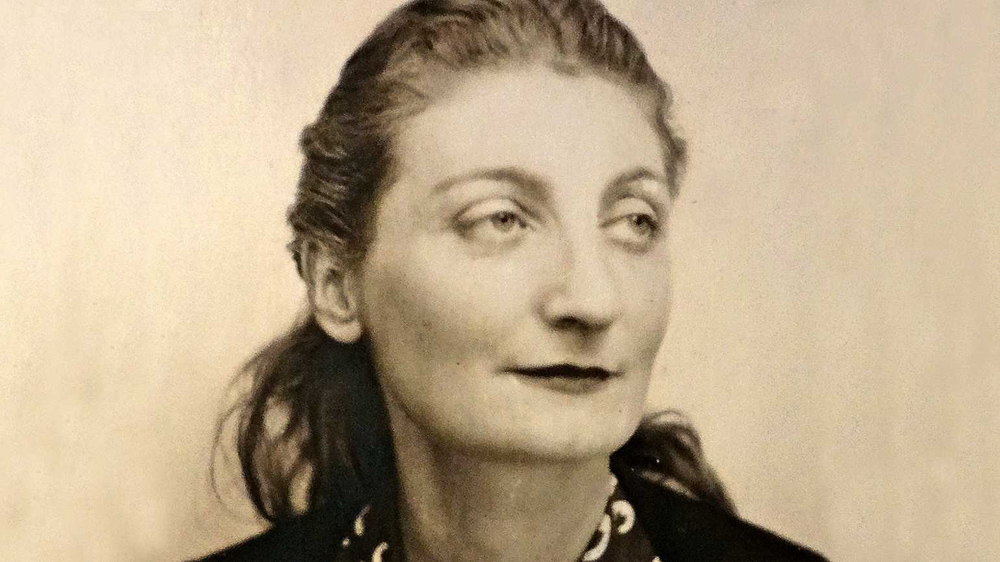

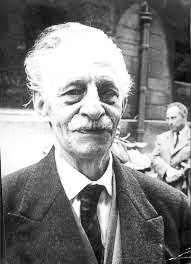

Do you ever wonder how rather obscure stories are resurrected from history’s dust bins? In the case of today’s blog, we have Anne Nelson to thank for uncovering the story of Suzanne Spaak’s resistance activities. Anne is the author of Suzanne’s Children (refer to the recommended reading section at the end of this blog for a link to her book). Anne came across Suzanne while researching her excellent book, Red Orchestra (again, refer to the recommended reading section). A haunting photo of Suzanne found in Leopold Trepper’s memoirs piqued Anne’s interest and initiated her nine-year journey. She was able to locate Suzanne’s daughter, Pilette, in Maryland and a series of three dozen interviews spread out over seven years formed the backbone of Anne’s research. There isn’t much out there regarding Suzanne’s story, so we owe many thanks to Anne for finding and “bird-dogging” the facts surrounding Suzanne’s activities. I’m quite sure she went down many rabbit holes while researching and writing the book. I have read both books and I look forward to Anne’s next book.

Did You Know?

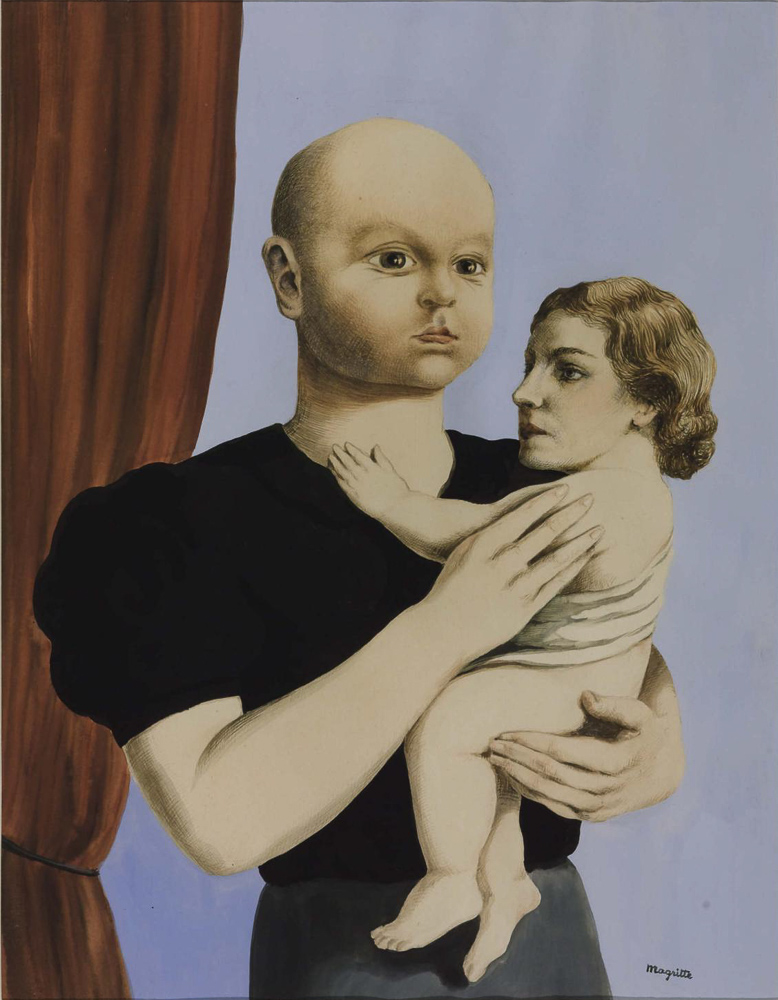

Did you know that the international art world was undergoing new movements during the interwar period (1918 – 1939)? Picasso, Dalí, and Magritte would each create styles of painting that today we call cubist and surrealism, among others. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Hitler (a frustrated artist in his youth), declared the work of these artists along with dozens more (including many German artists) as degenerate. René Magritte (1898-1967) was a starving Belgium artist whom Claude Spaak befriended while artistic director of the Brussels Palais des Beaux-Arts. Magritte supported himself by designing wallpaper and sheet music. Spaak began suggesting topics and themes for Magritte to paint. Soon, the Spaak family’s walls were covered with surrealistic images, the likes no one had ever seen. By 1936, Claude convinced his friend to paint family portraits. Probably the most disturbing was L’Esprit de Géométrie or, “Spirit of Geometry.” It is a creepy painting of a mother holding an infant. The problem: the head of the mother was Claude’s four-year-old son, Bazou and the infant’s head was Claude’s wife, Suzanne ⏤ Dalí would be proud. In 1937, Claude moved his family to Paris, but Magritte remained in Belgium where he continued to struggle. At one point, Magritte requested stipends from his patrons. Only Suzanne Spaak stepped up to the plate with a monthly stipend in exchange for paintings. The Spaaks would go on to collect forty-four paintings by Magritte. Five days after the Nazis invaded Belgium, Magritte fled to France where he immediately went to the Spaak’s country home. He requested to “borrow back” several paintings hanging on their wall. When Magritte left for Paris, he was carrying with him a dozen paintings. Magritte had been introduced to an American art collector to whom he would sell his “borrowed” paintings. The collector’s name was Peggy Guggenheim and the Spaak family’s paintings would ultimately end up hanging in her museum.

Let’s Meet Suzanne Spaak

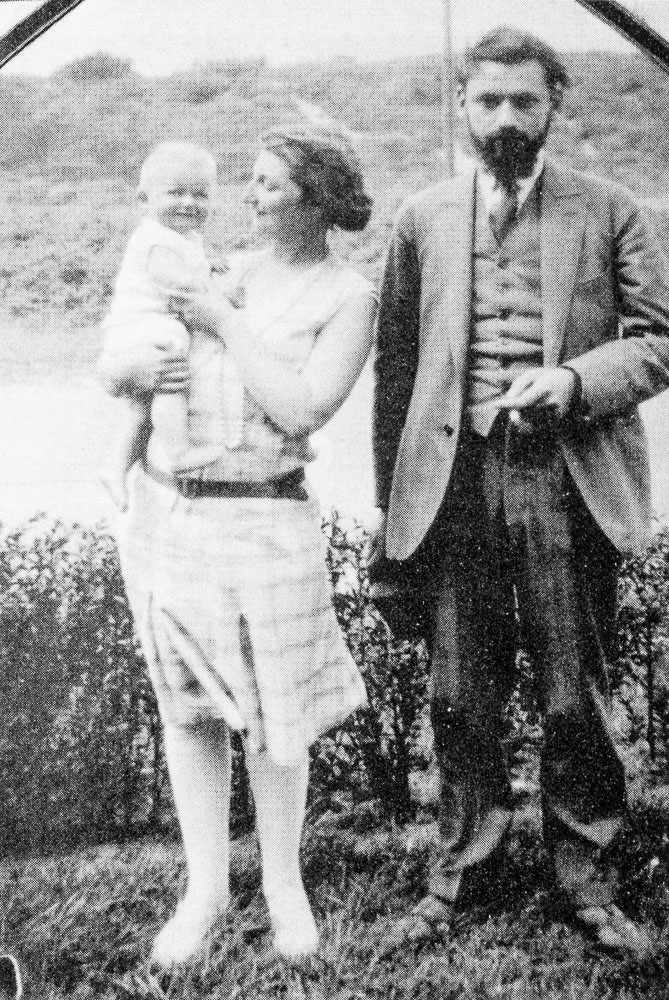

Suzanne Lorge Spaak (1905-1944) or “Suzette” as her family and friends called her, was born into an affluent Belgian family. Her father was a prominent banker and she married Claude Spaak (1904-1990) in 1925. Claude’s family included his brothers Paul-Henri who would become a well-known Belgian politician (Prime Minister and Foreign Minister among other positions) and Charles, a famous movie script writer. Suzanne and Claude had two children: Lucie (“Pilette”) and Paul-Louis (“Bazou”) but life together as husband and wife was not happy.

Claude was a philandering spouse with a terrible temper and Suzanne was aware of his escapades but because of the negative publicity affecting the two families, divorce was not an option. Instead, Suzanne asked her good friend, Ruth, to become Claude’s mistress (at least she would know where her husband was). By 1937, Claude decided being an art curator wasn’t fun and he began to write plays. After several were picked up by Paris theater producers, Claude moved his family to Paris ⏤all financed by Suzanne’s dowry and inheritance.

Pre-War Paris Politics

During the inter-war period (i.e., the years between World Wars I and II), Paris was politically divided between the “Left” and “Right.” Lining up on the Left were the Socialists, Communists, and the trade unions. Supporters of the Right were monarchists, fascists, right-wing, and generally, anti-Semitic. The idea of being a “capitalist” was destroyed after the Great Depression worked its way across the Atlantic. France’s government, the Third Republic (1870-1940), was considered to be corrupt and it was eventually dissolved and replaced with the Nazi collaborationist government located in Vichy, France.

Suzanne began her social work while living in Brussels and in 1932, joined the World Committee of Women Against War and Fascism. She supported the Republican forces during the Spanish Civil War.

The Occupation

Between 1880 and 1925, three and a half million Jews left Central and Eastern Europe. Two and a half million emigrated to the United States but in 1924, America closed its doors. France became the number one destination for future Jewish immigrants. By 1939, there were 150,000 Jews living in Paris of which 90,000 were foreign born. The majority of them settled into the Marais, Belleville, and Montmartre. After the Nazis invaded France, very few French Jews left the country. Jews believed Vichy would protect them from the Nazis because they were born in France or carried French citizenship and fought for France in World War I. Unfortunately for them, the collaborative Vichy government was filled with right-wing politicians and bureaucrats ⏤ all of whom were anti-Semitic.

During the summer of 1941, the Germans invaded the Soviet Union. Stalin urged all Communists to rise up against the Nazis in the occupied countries. Initially, the majority of the French resistance movement was driven by Communists and in particular, foreign-born Communist Jews.

During this summer, Claude and Suzanne moved the family into an apartment in the Palais Royal. One of their neighbors was Colette (author of Gigi and well-known French celebrity) and the Spaaks began to socialize with the intellectual elite of Paris such as Jean Cocteau.

In May 1941, the first major round-up of Jews in Paris took place when 3,800 men were arrested and sent to detention camps. Suzanne joined the Solidarité resistance movement founded in November 1940 by Polish Jews. It was commonly known as the MOI or, Main d’œvre immigrée. Initially, Suzanne was not trusted but very quickly, the MOI saw she was a dedicated résistant and more importantly, she was Catholic, pretty, and socially connected. It meant Suzanne could move around Paris and France pretty much as she wished. She became an important member of this Jewish resistance movement. Beginning with her involvement with the MOI, Suzanne’s children would assist her in resistance activities ⏤ Pilette would forge documents and Bizou would be a courier.

During the winter of 1941, Suzanne joined another resistance movement called the National Movement Against Racism or, MNCR. It was founded to oppose the “racial” laws imposed for the purpose of harming Jews. Unlike other resistance networks or organizations, the MNCR operated across political and religious lines. Suzanne was initially used as a courier and by 1942, she was working on their clandestine newspaper, J’Accuse (its editor, Mounie Nadler, would eventually be executed at Mont-Valérien).

After the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, the Nazis began their systemic murder of Jews. On 16/17 July 1942, the French police rounded up more than 13,000 Jews (the Nazis had demanded 22,000) of which 4,000 were children. They were sent to detention camps such as Drancy and from there, put on the train convoys to Auschwitz (Click here to read the blog, The Roundup and the Cycling Arena). As rumors spread through the Jewish community about the pending roundup, Suzanne distributed leaflets warning the residents in the Jewish neighborhoods. After the roundup and knowing 31% of the arrested were children, Suzanne said, “Something must be done.”

Union Generale des Israelites de France (UGIF)

In November 1941, all Jewish charity organizations were consolidated into the UGIF. The Nazis used the UGIF in their efforts to identify Jews, where they lived, and to control the Jewish community. All Jews were required to register with the UGIF and pay dues. One of the UGIF divisions was the orphanage which cared for the children whose parents had been deported. The Nazis did not require children under the age of sixteen to be arrested or deported. However, Vichy (and Pierre Laval) finally ordered Jewish children to be deported.

Rescue: Kidnapping the Children

Shortly after the Grand Roundup of July 1942, Suzanne began visiting Catholic priests, bishops, and even the Cardinal of Paris. She pleaded for the lives of the children and it resulted in letters sent to Pétain (president of Vichy), sermons about what was going on, and Catholics began to shelter Jewish children. The MNCR formed a committee to save as many children as possible from deportation. Suzanne was one of the committee’s founders.

By early February 1943, French police began going around to the UGIF orphanages and arresting children. It seems there weren’t enough adults to fill the convoy quotas demanded by the Germans. Suzanne quickly developed a plan to save the children.

Suzanne began to recruit Catholic women to impersonate family members of the orphaned children staying at the UGIF facilities. The children were allowed to go on walks once a week with someone who is a family member. She knew that once out of the orphanage, the children would need to be fed, clothed, and sheltered. So, Suzanne enlisted the aid of the pastor of a local Protestant church. Pastor Paul Vergara and his wife were active in the Oratoire du Louvre, a Protestant resistant network. Marcelle Vergara and a social worker, Marcelle Guillemot, ran the soup kitchen in the church basement and provided the first destination point for the rescued children. After that, they would be placed in safe homes around the countryside which Suzanne had earlier identified and made arrangements.

Suzanne recruited forty women: twenty-five Protestants and fifteen Jewish. On the morning of 15 February, Suzanne and Pilette met up with the forty women and one group goes to the UGIF orphanage at 16, rue Lamarck while another group went on to another UGIF facility at 9, rue Guy Patin (both of these buildings are stops in my new book, Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?) Each woman identified themselves as a family member and took a child (or two or three) out for their “walk.” The operation was a success and it is generally acknowledged that sixty-three children were saved. The Germans learned about Suzanne’s involvement and they eventually caught up to her but for a different reason.

Arrest

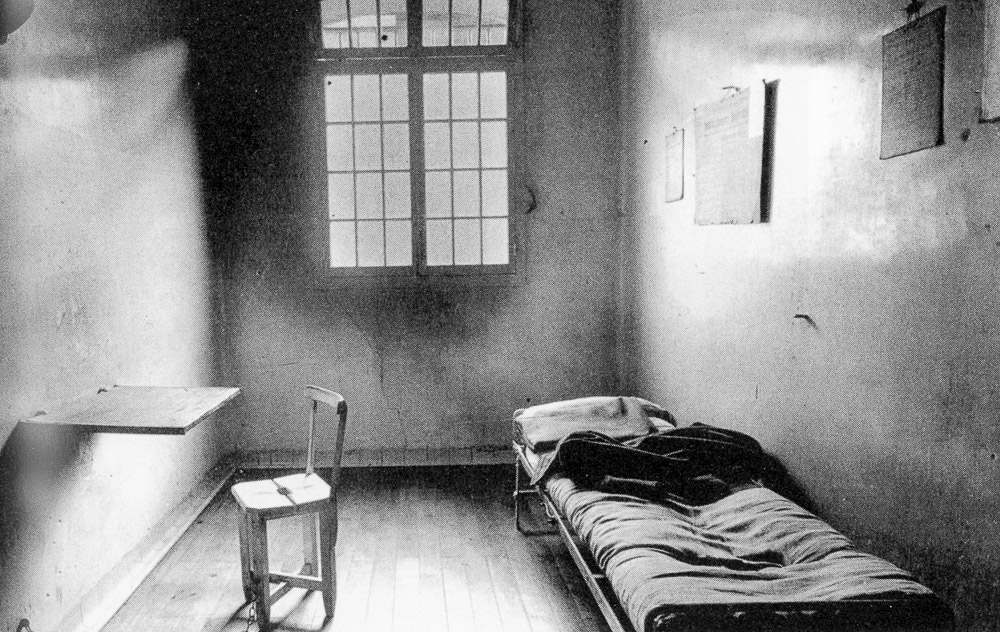

Suzanne became involved with Leopold Trepper and his resistance network, The Red Orchestra (Click here to read the blog, Die Rote Kapelle). The Gestapo had infiltrated the network and had a list of Trepper’s agents, including Suzanne. She and the children fled to Brussels in mid-October 1943. On 24 October, the Gestapo visited Suzanne’s mother’s house (coincidentally, the house was across the street from Gestapo headquarters) and demanded to speak with Suzanne. She was not there but shortly afterwards; Suzanne went into hiding in the Ardennes. She was ultimately betrayed by a friend and on 10 November, Suzanne was arrested by the Gestapo. Put on trial in a Luftwaffe court in January 1944, Suzanne was found guilty and sentenced to death. She was transferred to Fresnes prison where one of her neighbors in the cell block was Geneviève de Gaulle, the general’s niece (Geneviève would survive the war and Ravensbrück concentration camp).

Suzanne began her long wait.

Execution

By the beginning of August 1944, the Allies had broken out of Normandy and were on their way towards Berlin. The Germans in Paris were preparing for their evacuation from the city. It was chaos during those final days. The Nazis were destroying documents, setting explosives around the city, fighting the résistants and Paris citizens in the streets, frantically looting whatever they could send back to Germany, and deporting as many Jews as they could in the final convoys leaving Paris. The Gestapo and the SS were also making sure they didn’t leave any prisoners.

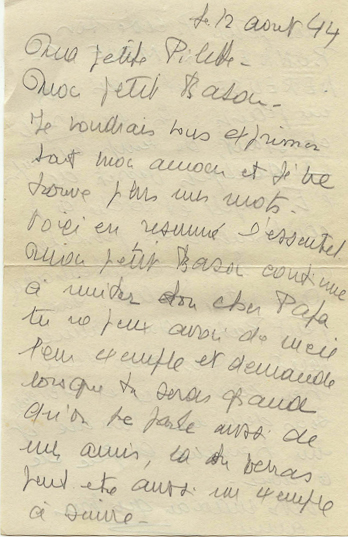

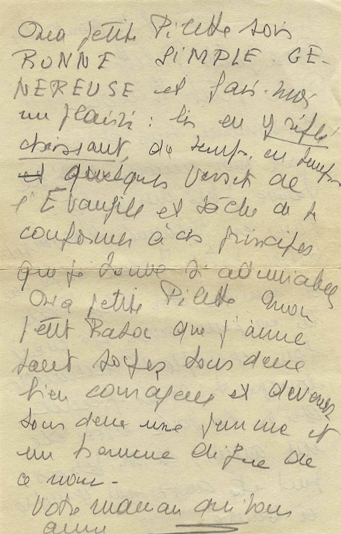

On the morning of 12 August 1944, Suzanne sat down in her cell and wrote a long letter to her children. Shortly after finishing the letter, Suzanne and one other prisoner were taken into the prison courtyard, told to kneel down, and were shot in the back of the neck.

There is some historical speculation that Suzanne had received a pardon from Berlin, but the paperwork had been lost or overlooked during those last days of the Occupation.

Thirteen days later, Paris was liberated.

Post-War

While Suzanne sat in jail, Claude and Ruth hid out in silence. After the war, they were married, and Claude destroyed all evidence of his marriage to Suzanne. He never talked about Suzanne and the children didn’t learn where their mother was buried until 1956. Claude and Ruth lived a life of luxury financed by Suzanne’s estate. Whenever they needed money, he would sell a Magritte painting.

When Bazou was a teenager, Claude said to him, “I really don’t know what I would have done if your mother had come back.” Bazou has never forgiven his father for that remark.

Approximately 11,000 children were deported to Auschwitz (representing 15% of the French Jews deported). Rescue networks like the one Suzanne ran saved more than one thousand children from being deported.

Humanitarian and “Righteous Among Nations”

When we speak today of a “resistant,” we use this term to classify all of the men and women who fought the Nazis in their respective occupied countries. If Suzanne Spaak had survived the war, her friends said she would have preferred to be labeled under a different term: HUMANITARIAN.

On 21 April 1985, Suzanne was recognized by Yad Vashem on behalf of the State of Israel and the Jewish people as “Righteous Among the Nations.” It is an honor bestowed upon non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. There are four basic conditions someone has to meet to be considered. One of the four criteria is that the motivation to assist was not driven by personal gain.

Suzanne Spaak’s motivation was her love of children.

Recommended Reading and Viewing

Nelson, Anne. Suzanne’s Children: A Daring Rescue in Nazi Paris. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

Nelson, Anne. Red Orchestra. New York: Random House, 2009.

This is an excellent book for those of you who want to expand your knowledge about Suzanne and the plight of Jewish children in occupied Paris. Ms. Nelson is also the author of Red Orchestra. It is a good read about Leopold Trepper and his resistance network.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew

We are trying to branch out into the community with some of our presentations. We had a very successful “snow bird” season here in Punta Gorda with respect to building an on-going audience for our lectures. We’re approved for three new programs for next season. Sandy will be adding a new section to the web site where you can see the dates and topics ⏤ check it out now since you’re already on the web site. Hope some of you can join us. Check it out here.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thank you to John W. who attended all three of our presentations at the Renaissance Academy. I appreciated his kind words concerning the presentations. Those are the type of comments that keep us going. One of the Amazing Women of the French Resistance whom we covered was Marie-Madeleine Fourcade, the leader of the Alliance network which ran the Comet Escape Line. John recommended I get Lynne Olson’s new book Madame Fourcade’s Secret War. Coincidentally, I had picked her book up from the post office an hour before I received John’s e-mail. Thanks John and we’re looking forward to seeing you again next season for our presentations.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs. Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright ©2019 Stew Ross

I had the pleasure of meeting and staying with Lucie “Pilette” Spaak Bennani in Brunoy, France in Sept. of 2015. Anne Nelson was in the process of writing Suzanne’s story”Suzanne’s Children”. Lucie is also known as Malika, a name given to her in Morocco where her husband was from. Lucie is a fascinating person, now age 92. Ou correspondence dwindled around the end of 2017, possibly due to eyesight issues. i recently typed her a larger font, 3 page letter. So far, no response. I live in Castle Rock, Colorado, USA

Thank you Linda for your comments. It’s very interesting when I hear from people like you who have had the experience of meeting with the children of these French Resistance heroes. In this case, Pilette was a résistant as a young girl. I believe Pilette is still alive but perhaps no longer able to respond to letters. I hope that’s not the case. I have a friend in Paris who is good friends with a woman whose mother was a SOE agent and executed by the Nazis. Thanks again for reaching out to us. STEW

Very well done! interesting article and the part about Magritte borrowing the paintings intrigued me. Where can I read more about it/ may you kindly share the reference?

thanks!

Hi Kela; thank you for reaching out to us. I’m glad you enjoyed the blog. The Magritte aspect added an additional dimension to Suzanne’s story, didn’t it? I would direct you to Anne Nelson’s book, “Suzanne’s Children” (I listed it at the end of the blog under “Recommended Reading.”) As far as a specific reference on Matisse, I’m afraid I don’t have one to recommend. STEW

I also had the pleasure of the company of Lucie Spaak Bennani (known to me as Malika) around 2014 & ’15. We met through a mutual love of knitting, and remained friends after I left Paris.

When I knew her, she was always full of stories, often of escapades during the war. She was the life and soul of our knitting group. An incredible woman with such a fascinating story, but I know my friend Malika as a fantastic craftswoman and wonderful cook.

Thank you for sharing their story.

Hi Julia; Thank you for letting us know about your friendship with Suzanne’s daughter. I wish I had been a fly on the wall while Malika was discussing her wartime stories. While an uplifting story, it certainly was a tragic end for the family. Thanks again for your comments and I hope you will enjoy not only our past blogs but the ones coming up in the future. STEW

Hi Stew,

Thank you for the wealth of information about Suzanne Spaak. I met Malika when she lived in the States before moving to France to be with her son. She told me many stories. She was very involved with a knitting group here in Maryland, and I met her through the group. I also had a chance to speak with Ann Nelson about her books. I am particularly interested, because my father escaped Vienna with his parents when he was a child around 1938. He now volunteers at the US Holocaust Museum. I hope to connect with you soon.

Sincerely,

David

Hi David; You are the third person to contact me regarding Malika and developing a friendship with her. I’d like to learn more about your father’s experiences during those years. I hope you’ll consider subscribing to our bi-weekly blog posts. STEW

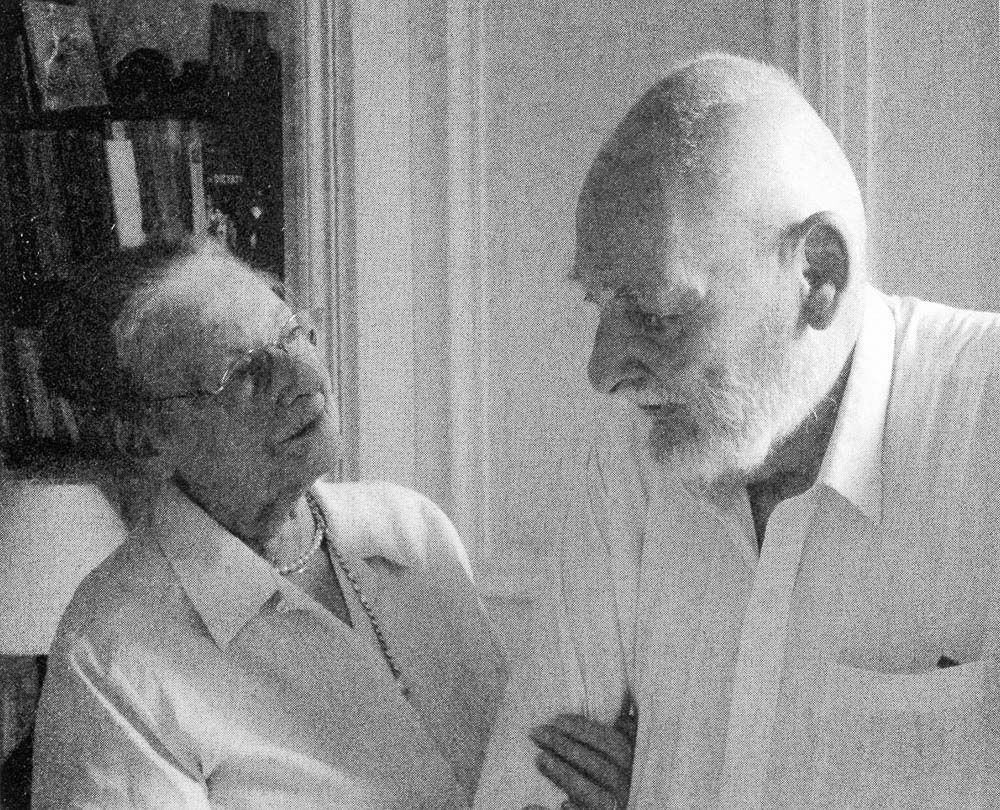

Reading about Suzanne’s heroism and tragic ending helps me to better understand Paul-Louis. I had the pleasure of meeting him and his wife in Paris during the mid-80s and of seeing many Magritte paintings in Claude’s country home. One of them depicted Paul-Louis as an adolescent (that makes at least two paintings by Magritte featuring Paul-Louis). The relatively recent 2015 photo of Paul-Louis and Lucie is beautiful as well.

Thank you for publishing this fascinating and educative article. It is uplifting for its account of the best of humankind under extreme duress.

Hi Susan, Thanks for reaching out to us. You are like the fourth or fifth person who has contacted us regarding having met met Suzanne’s children. It’s wonderful that you got to know them. It is a fascinating story and very tragic about their mother. Hope you enjoy our future blogs as well as some of the past ones. STEW