Historically, people have reacted in three primary ways to totalitarian and fascist regimes such as Hitler and his Nazi party: they support it, they oppose it but do nothing or, they oppose it and become a resistance fighter (in small or large ways).

We normally associate resistance to the Nazi regime as something that occurred in the occupied countries. As we saw in our last blog (Hitler’s Blood Judge, click here to read), there were organized resistance movements, albeit limited, within Germany (e.g., The White Rose Movement). Unfortunately, the Gestapo and other police units were able to effectively shut them down and turn the “traitors” over to the show-trials presided by judges such as Roland Freisler.

However, there were several well-known German resistance organizations which operated not only in Germany but in several of the occupied countries and one neutral country. As we’ll see, several of them were quite successful during the limited time they had. Because it was assumed the resistance groups reported to Moscow, the Gestapo gave them the collective name of Die Rote Kapelle or, The Red Orchestra.

Did You Know?

Another organization the Gestapo and the S.D. or, Sicherheitsdienst (the SS intelligence service) targeted was Die Swartz Kapelle or, The Black Orchestra. Led by General Ludwig Beck, the Black Orchestra was a loosely organized network of high-ranking German Wehrmacht and Abwehr officers. During the mid-1930s, they believed Hitler was rushing to war before Germany was adequately prepared. Their initial opposition was not based on replacing Hitler, rather trying to convince him to wait until the country was ready to wage a successful war.

However, by the late 1930s and in particular, after the Munich Agreement, the clandestine military opposition changed to a goal of overthrowing Hitler. During 1938 and 1939, numerous plans to assassinate Hitler were drawn up including the failed attempt to detonate a bomb on Hitler’s airplane. By spring 1940, Hitler’s successful strategies enhanced his reputation with the Germans and the conspirators began to dissipate because they felt the general public would not support a regime change.

However, by the summer of 1943, Operation Barbarossa (the invasion of the Soviet Union) had failed and Hitler didn’t look like the genius everyone thought he was only four years earlier. At that point, questions were beginning to be asked about Germany’s ability to win the overall war. The conspiracy to overthrow Hitler was revived albeit with less participation than before. By this time, the Gestapo and the S.D. had caught onto the discontent at the top of the military chain. One of the leaders of the Black Orchestra was Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr—the German intelligence organization which reported up through the high command of the Wehrmacht (as opposed to the competing intelligence agency, the S.D. which reported to Heinrich Himmler). Other members of the Black Orchestra or at least willing participants, included the German ambassador to Rome, the mayor of Leipzig, most of Canaris’s staff, Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, General Ludwig Beck, Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, General Carl-Heinrich von Stüpnagel (the German Military Governor of Paris), and other high-ranking officials. There were enough well-placed officers to support Colonel von Stauffenberg’s plot to kill Hitler on 20 July 1944.

Operation Valkyrie failed and the Gestapo had no trouble rounding up the Black Orchestra conspirators (and their families). Gestapo records indicated more than 7,000 people were executed as part of their role in the conspiracy. General Beck attempted suicide but only wounded himself—a soldier was sent into the room to finish off the job. The Black Orchestra ceased to exist at that point.

Die Rote Kapelle

The Red Orchestra received its name because the Nazis considered these resistance groups to be run by Communists and the Soviet Union. Red Orchestra was an all-inclusive term used for three separate groups: the Lucy spy ring, the Trepper Group, and the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack Group. Members of these groups were predominately intellectuals who either were Communists or who leaned towards Communism. Resistance within Germany by the intellectual community was divided into three categories: “Inner Emigration” was the term given to the intellectuals who left the big cities and moved to a rural setting to wait out the war. The next step was Resistenzor, the daily act of resisting by noncompliance with certain expected behaviors. These might include refusing to give the Nazi salute or not contributing to fund-raising efforts for the war. The last and most dangerous act of overt resistance was called Widerstand or, “taking a stand against” the Nazi regime. The Red Orchestra was committed to Widerstand and each member knew the consequences if caught. Watch the documentary movie trailer here.

Almost immediately after Hitler took power in 1933 the suppression and brutality by the Nazi regime began. Hitler ordered the SS and the thugs known as the SA (the Brownshirts) to first target his political opposition. These were the Communists and the Social Democrats (the socialists). The Nazis were brutal in their treatment of these two groups. If you weren’t executed, you would likely end up in Dachau or other concentration camps which were originally built to hold political prisoners. If you were lucky, all they did was savagely beat you up. By 1935, more than half of the 422 leaders of the KDP (the German Communist Party) had been thrown in prison or a concentration camp. Twenty-four were murdered, forty-one left the party, and 125 went into exile. Only thirteen of the original 422 remained active inside Germany.

The French Resistance was fragmented from the beginning. During the early years of the Occupation, Communists or people sympathetic to Communism made up the majority of the réseau or, networks. Besides defeating the Germans, the French Communists had a secondary goal of taking power after the war. So, they didn’t trust resistance members who supported Charles de Gaulle and vice versa. The Vichy government turned a blind eye to the British led intelligence organizations such as Special Executive Operations (SOE) but they hated anyone associated with de Gaulle. Even within the British intelligence community there were competing departments and agencies. All of these factions at odds with one another made it difficult to present a cohesive counter to the German occupation of France.

Another problem encountered by the French Resistance was the relative lack of security. While they did their best to prevent breaches of security, some basic safeguards were disregarded (e.g., meeting in the same restaurants or bars and openly boasting of being in the resistance). As the size of the movement and individual networks grew, it became harder to keep double agents from infiltrating the réseau and betraying the résistants.

Nazi intelligence and their ability to track down resistance organizations and arrest its members came down to several primary tactics. One of the most effective was their ability to turn captured resistance members into double agents. This was accomplished when information was exchanged for the promise their families would be protected. Another tactic to “turn” a high-level arrestee was the Gestapo promise not to execute anyone from their network if the resistance leader divulged the names of every member still at large.

Besides infiltrating the networks, the most damage was a result of the Nazis ability to monitor the multitude of radios used by the networks to report back to London. This program was administered by the OKW Funkabwehr or, Radio Defense Corps of the Armed Forces High Command. After locating a transmission location, the radio operator would be arrested and the Nazis would confiscate the radio and code book. The next phase known as Funkspiel resulted in the Nazis impersonating the radio operator. They would send and receive messages with the intent to deceive the British. Through Funkspiel, the Germans were able to cripple the SOE in and around Paris.

The Lucy Spy Ring

The Lucy spy ring operated out of Switzerland, a neutral country during the war. The leader was Rudolph Roessler (1897−1958), a young newspaper man who tried to warn his fellow Germans about Hitler and the Nazi party. He fled to Switzerland after Hitler took power. During his four years in the German army during World War I, Roessler met the soldiers who would later provide him with high-level military information which he would in turn, pass on to the Allies. Of the three organizations in the Red Orchestra, the Lucy spy ring was the most effective.

Roessler was approached by several German officers who were part of the conspiracy to replace Hitler. They convinced Roessler to be the conduit between the Allies and the information they would supply him. These men were in high level positions (i.e., operations, logistics, transport, military, and most importantly, communications) with access to classified information. They supplied Roessler with a radio (nicknamed Lucy—short for Lucern, Switzerland). He and his German operatives believed in only one thing—the defeat of Hitler and the Nazis. Roessler would pass the information on to the country he felt gave them the best chance of achieving their goal of overthrowing Hitler: The Soviet Union.

The amount of information Roessler collected and dispersed was immense. It is said that he sent almost 130 messages per month over a period of three years. This information included troop movements, invasion timetables, production statistics, and the equipment lost in each battle. The one piece of information that really made the Soviets wake up to the effectiveness of the Lucy spy ring was the warning that Hitler was about to attack Russia—Operation Barbarossa. Unfortunately, Stalin refused to believe it. However, after the invasion on 22 June 1941, the Soviets considered Roessler to be one of their most important sources of trusted intelligence and future messages were reviewed immediately including advance notice of where the Germans would attack the Soviet army next.

All of Roessler’s known German contacts survived the war. Roessler became a post-war freelance journalist but got into financial difficulties. During the early years of the Cold War, he returned to espionage and worked on behalf of the Czechoslovakian government. Low level information about the United States, Britain, and France (the three countries occupying Germany along with the Soviet Union) was forwarded to his handlers. By 1953, Roessler was arrested in Switzerland and charged with spying. He was found guilty and served nine-months in prison before being released. After his death in 1958, testimonials from high-level officials acknowledged that Roessler’s transmissions were critical to the Allies’ efforts to win the war.

The Trepper Group

Leopold Trepper (1904−1982) is considered to be the founder of the primary Red Orchestra group. Prior to the war, Trepper was a Communist agent for the Palestine Communist Party and worked in France until 1932 when the French broke up his network. He left for Moscow but traveled frequently between Paris and Moscow over the next six years.

His first network dedicated to Nazi resistance was based out of Belgium. Trepper’s alias was a Canadian businessman who invested in a business that supplied product for the Todt Organization, a German/Nazi organization responsible for construction of key Nazi military structures. The Gestapo discovered his Belgium network in December 1941 and Trepper fled to France. The two male agents and their female courier arrested in the Gestapo raid weren’t so lucky—all were executed by guillotine. Code books were discovered and hundreds of Soviet agents were identified.

Setting up a similar group in Paris, Trepper’s network was eventually broken by the Abwehr and he was arrested in December 1942. It is likely the Nazis were successful in turning Trepper into a double agent but it is speculative with respect to how much damage he did. By the spring of 1943, Trepper’s network had been completely infiltrated by the Gestapo and ceased to exist. Trepper was able to escape his captors in 1943 and immediately went underground. He joined the French Resistance after the liberation of Paris.

After the war, the Soviets rewarded Trepper with a lengthy prison sentence and for unknown reasons, he avoided being executed. After his release in 1955, Trepper moved to Poland and subsequently, to Israel where he lived in Jerusalem until his death in 1982. While Rudolph Roessler and Leopold Trepper survived their wartime spying activities, the leaders and dozens of members of the next resistance network weren’t so lucky.

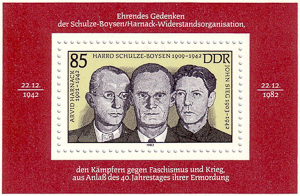

The Schulze-Boysen/Harnack Group

This group was the result of combining two separate German resistance networks in 1939. The members posted anti-Nazi literature around Berlin in addition to helping people leave Germany. They gathered intelligence information which was then passed on to the United States Embassy in Berlin (prior to 7 December 1941).

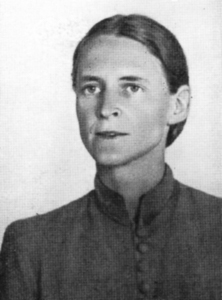

Arvid (1901−22 December 1942) and Mildred Harnack (1902−16 February 1943) formed a resistance organization that distributed anti-Nazi material, assisted Jews, forced laborers, and documented Nazi acts of violence (Arvid was fond of saying that after the war, people were going to have to be held responsible for their actions and he wanted to provide the visual and written evidence). Mildred was an American citizen and as such, had close ties to the U.S. Embassy. Arvid was an official in the Economics Ministry where he could obtain classified war information. Learn more about Mildred Harnack here.

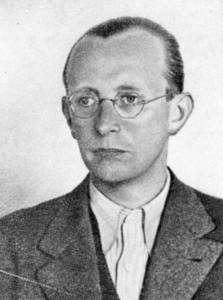

Lt. Harro Schulze-Boysen (1909−22 December 1942) was a member of Field Marshall Hermann Göring’s staff. Prior to joining the Nazi party as a cover for his resistance activities, the twenty-three-year-old was the publisher of a left-leaning periodical called Der Gegner. In 1933, the SA or, the Brownshirts, raided the offices of Der Gegner and beat up Schulze-Boysen leaving swastika carvings on his back. He formed a spy ring in 1935 and offered his services to the Soviets and they gladly accepted. As an officer on the Luftwaffe staff, Schulze-Boysen had access to high-level information which was transmitted to a Soviet intelligence agent. His wife, Libertas, a family friend of Göring, joined Harro’s spy network and passed along information she received through her interaction with the field marshal (albeit, unbeknownst to him).

Missteps, Gross Errors, and Arrests

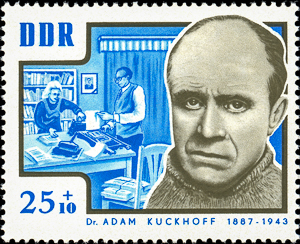

The downfall of the Red Orchestra came as a result of errors made by Soviet intelligence in Moscow and “Kent,” one of Trepper’s agents in Brussels. The Gestapo had been monitoring radio transmissions from Moscow to the Red Orchestra when the Soviets wired the names and addresses of Adam Kuckhoff and the Schulze-Boysens to Soviet agents in Belgium. A few months later, Kent transmitted material from Harnack and Schulze-Boysen for seven nights in a row, several hours each night. It gave the Gestapo enough time to trace the transmissions.

The Gestapo raided Trepper’s Belgium headquarters and arrested several of his agents including the courier, Rita Arnould. Under “questioning,” Arnould told them everything and shortly afterwards, the Nazis had the resistance network’s code book in their hands. On 31 August 1942, Harro Schulze-Boysen was the first of hundreds to be arrested. The Gestapo tracked down the Harnacks and Libertas Schulze-Boysen followed by Adam and Greta Kuckhoff several days later. During the fall of 1942, the prisoner count totaled more than 120 with the men held in the cellars at Gestapo headquarters (on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse) and the women incarcerated at the Alexanderplatz prison.

Mildred attempted suicide but was not successful. However, others knew they would break under the interrogation and committed suicide, including John Sieg, for the purpose of protecting others. Hilde Coppi and Liane Berkowitz were pregnant at the time of their arrests. Libertas held out hope because of her Göring connection. Adam Kuckhoff broke under torture and gave the Nazis the names of the last remaining Red Orchestra members still at large. By October 1942, the Gestapo had enough information on the group and its members to turn the files over to the court. The outcome was pre-determined when Hitler ordered “the Bolshevists within our ranks” to be immediately executed and without any mercy.

The Trials

The prisoners were put on trial in December 1942 for treason and spying for the Soviets. Göring handpicked the military judge: Manfred Roeder (1900−1971). Along with Roland Freisler, Roeder earned the title of Hitler’s “blood judge” (click here to read the blog Hitler’s Blood Judge) and certainly lived up to it in the trials of the Red Orchestra. Harnack, Schulze-Boysen, and Kuckhoff had confessed to Soviet espionage which was considered high treason and carried an automatic death sentence. Seventy-six people were put on trial while the rest were released due to a lack of evidence. The harshest treatment was saved for professionals, intellectuals, military, and others whose origins were rooted in higher society compared to the working class.

More than twenty Red Orchestra trials were held with the first one beginning 16 December 1942 and only four lawyers agreed to defend the accused. The first trial of thirteen defendants included Harro and Libertas Schulze-Boysen, Arvid and Mildred Harnack, the Schumachers, and the radio operator, Hans Coppi. While twelve defendants claimed they were motivated by a hatred of the Nazis, Libertas blamed her husband and demanded a divorce.

All but two of the thirteen received the death sentence. Mildred and one other woman got lengthy prison terms. However, Hitler was furious when he found out and overrode the two verdicts and another quick trial was held in which the women were sentenced to die.

Subsequent trials were held through July 1943. Forty-five defendants including Greta and Adam Kuckhoff, the pregnant Liane Berkowitz, and Cato Bontjes van Beek were condemned to die. Twenty-nine were sentenced to prison and two were released for lack of evidence.

The Executions

The guillotine at Plötzensee prison was located in the execution shed where thousands of German, Polish, and Czech underground operatives had previously been guillotined. The guillotine was considered a “humane” method of execution and Hitler would have nothing to do with that for traitors, especially the men. He had a steel beam installed at the far end of the execution shed with eight meat hooks attached. Most of the condemned men were hanged by piano wire.

The guillotine was reserved primarily for the women and on 22 December 1942, it began with Libertas who, unlike the others, went to her death in a most undignified way. That evening, eleven leading members of the Red Orchestra were executed at Plötzensee—five were hanged and six by the guillotine. The men included Schulze-Boysen and Harnack.

Mildred was executed on 16 February 1943 and her last words were “And I have loved Germany so much!” Mildred was the only American woman executed by the Nazis. Shortly after her execution, Arvid Harnack’s brother was caught by the Gestapo and arrested for treason as a member of the White Rose (click here to read Hitler’s Blood Judge).

By early August 1943, they were all gone including Adam Kuckoff, Cato Bontjes van Beek, and the teenager, Liane Berkowitz. The bodies of the women were sent to a Nazi doctor at one of the medical institutes where he performed dissections to support his gynecological experiments. Their remains were never located—except for Mildred Harnack. The doctor knew Mildred’s family and he recognized her. He turned her remains over to the family for burial.

Miraculously, after being condemned to death, Greta Kuckoff (1902−1981) had her sentence commuted to ten-years in prison. Roeder had been re-assigned to other cases and Hitler turned his attention elsewhere. Greta served her sentence making gas masks in a prison outside Berlin. She was liberated by the Russians and lived out her life in East Germany as a successful banker and politician.

Cold War

One of effects of the Cold War was to lump all of the Red Orchestra as Communist party members. It wasn’t until the end of the Soviet Union and its archived documents were opened to historians that it became clear not every resistance member was a Communist or that the intelligence they gathered was intended solely for the Soviets.

The judge and prosecutor, Manfred Roeder was never brought to trial. The Allies (in particular, the U.S. Central Intelligence Committee or CIC) protected him since they wanted to use his skills during the early days of the Cold War to hunt down Communists including the surviving members of the Red Orchestra. He was not the only high-ranking Nazi protected by the Allies but that’s a story for a future blog post.

By 1947, the Cold War was in full swing. Interest in hunting down former Nazis let alone prosecuting them had waned. Denazification efforts were being neutralized by the belief that Communism and the Soviet Union were far worse than Hitler and Nazism. In other words, the crimes committed by the Nazis were either being forgotten or swept under the rug.

Recommended Reading and Viewing

Nelson, Anne. Red Orchestra: The Story of the Berlin Underground and the Circle of Friends Who Resisted Hitler. New York: Random House, 2009.

Trepper, Leopold. The Great Game: Memoirs of a Master Spy. London: Michael Joseph, Ltd., 1977.

Ms. Nelson does a great job of presenting the Nazis’ pre-war brutality which began almost immediately after Hitler took power. We think in terms of the Nazis’ persecution of the Jews but it is interesting to read about how they annihilated the Communists and Socialists before turning their full attention to the Jews.

Keep in mind that Trepper is likely trying to sanitize his involvement as a double agent. However, it is a first-hand account of an insider’s activities in Paris.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

You might not be aware of this but we are huge football fans. No, not the NFL or college football—we don’t watch any of that (except maybe for Michigan football when we’re not traveling during the fall). I’m talking about what we Americans call soccer and we’re the only ones who call the game by that name. By the way, I’m writing this on the day after Argentina lost 3−0 to Croatia during group play in the largest sporting event in the world: The World Cup.

One of my daily pleasures is reading the Wall Street Journal (WSJ). They are doing a wonderful job reporting on the World Cup. Before I get to the punch line, I’m going to switch gears on you. Writing blogs, books, or letters to the editor (which I’m now 8 for 8 getting printed in the Charlotte Sun newspaper), I’ve learned the title means everything (remember the blog entitled Cyndi Lauper and the Naked Princess? —highest number of clicks we’ve ever had (click here to read).

The title of the feature article in the WSJ today (22 June 2018) is “IT’S TIME TO START CRYING FOR AGENTINA.”

We loved it.

P.S. Go France and England! Each made it to the knockout round. By the time you read this, we should be getting close to the final match.

Someone is Commenting On Our Blogs

Sandy and I were introduced to Jack and Kim H. by our good friend John W. We had cocktails with them the other day over at the Celtic Ray. It seems Kim bought the first volume of the medieval book and was hooked. Her kind words and enthusiasm is what keeps us going, so thanks Kim.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2018 Stew Ross