In May 1945, several senior Gestapo officials made their way to Dahme, Schleswig-Holstein (northern Germany on the Bay of Lübeck) to prevent their arrest by the Allies. Officials at the British Field Security Post in Lübeck learned about these men and their hiding place from a captured Gestapo man. Immediately, British military police drove 31 miles to the Strandhotel and arrested five former Gestapo men ⏤ two officers and three NCOs. Taken back to Lübeck, the prisoners were turned over for interrogation at the city’s Marstall prison.

One of those men was SS-Sturmbannführer and Kriminaldirektor, Horst Kopkow. At the time of his arrest, Kopkow was a relatively unknown Gestapo official but as time went on and the British interrogated former Gestapo men, Kopkow’s name kept being brought up. It turned out he was the department chief responsible for counterintelligence (i.e., arresting foreign agents), the German radio program known as “Funkspiel,” and well-regarded by his superiors for his knowledge of Soviet espionage.

After extensive official and unofficial investigations, it became clear that Kopkow was personally responsible for sanctioning the torture and ordering the executions of foreign agents of MI6 and the British-led Special Operations Executive (SOE). I’ve written before about Hitler’s “enablers” (click here to read the blog, Hitler’s Enablers – Part One – Wannsee Conference and here for Hitler’s Enablers – Part Two – The Camps). Kopkow was an enabler but as Stephen Tyas points out in his book (see below), the Gestapo chief was a “desktop murderer.” He never personally pulled the trigger or hanged a prisoner, but he signed the Sonder behandlung, or “Special treatment” orders from his Berlin desk. In the end, he escaped justice because of the protection provided by British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), or MI6.

Did You Know?

Did you know that one individual was responsible for preparing France for the invasion of Normandy (i.e., D-Day)? During World War II, Jean-Louis Crémieux-Brilhac (1917−2015) served as Gen. de Gaulle’s propaganda chief. As the preparations for the Normandy invasion intensified during early 1944, M. Crémieux-Brilhac was assigned the responsibility for telling French citizens how to react once the inevitable invasion took place and efforts to liberate France began. He was secretary of the Free French Propaganda Committee, and he drew up four pages of instructions to “all French men and women not organized in, or attached to, a Resistance group.” Those instructions were handed over to the French service of the BBC. Separate orders were drawn up for broadcast to members of the Maquis. (These were the famous “personal” messages read out on the BBC in advance of the invasion ⏤ click here to read the blog, Dah-Dah-Dah-Duh.)

Crémieux-Brilhac’s messages were directed to the population in general as well as specific instructions to mayors, police, factory workers, etc. The biggest disagreement about the “call-to-arms” was between the Communists and the Gaullists. Communist resistance fighters were very influential in the French Resistance, and they demanded an all-out insurrection (i.e., general worker strikes and armed insurrection) on the eventual day of the invasion. M. Crémieux-Brilhac and the majority resisted the Communists’ demands and the majority won.

The instructions to the French were that “all French must consider themselves as engaged in the total war against the invader in order to liberate their homeland.” He made it clear that the French were to consider themselves “all soldiers under orders” and “Every Frenchman who is not, or not yet, a fighter must consider himself an auxiliary to the fighters.” Citizens living within the Normandy combat zone were instructed to “disrupt using all means transport, transmissions, and communications of the Germans.”

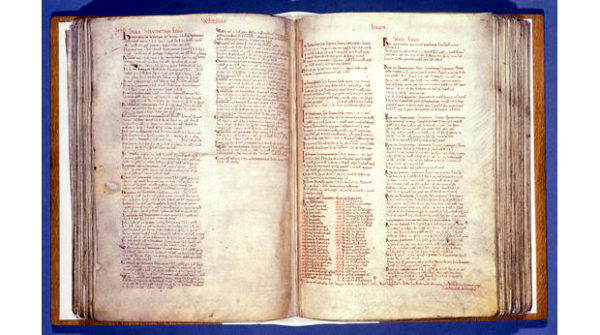

After liberation, the original instruction documents were retained by M. Crémieux-Brilhac. Upon his death in 2015, the papers were donated to the French National Archives.

Let’s Meet Horst Kopkow

Horst Kopkow (1910−1996) was born in East Prussia, Germany (now Poland) as the sixth child of a businessman and hotel owner. His childhood city, Allenstein, was overrun by the Russian army during the first world war and two of his older brothers died in the trenches on the French battlefields. These memories heavily influenced his vision of Russia and later, the Soviet Union with Kopkow vowing to fight Communism the rest of his life. Read More Desktop Murderer & British Agent