For those of you who follow our bi-weekly blogs, you know that I enjoy writing about the French Resistance and the exploits of those brave men and women during World War II. However, France was only one of many German occupied countries during the war. Each country had resistance organizations and I don’t mean to slight any of them just because I don’t write about them. Well, today is different.

One of my favorite authors, Caroline Moorehead, recently published her new book, A House in the Mountains. It is the story of Italian partisans and in particular, four women who fought fascism and the Nazis in Italy. While there are many similarities between the French and Italian resistance movements, one aspect stands out. That is, the large number of Italian women who actively participated in resistance activities against both the Nazis as well as many of their own countrymen who were staunch fascists and collaborationists.

Did You Know?

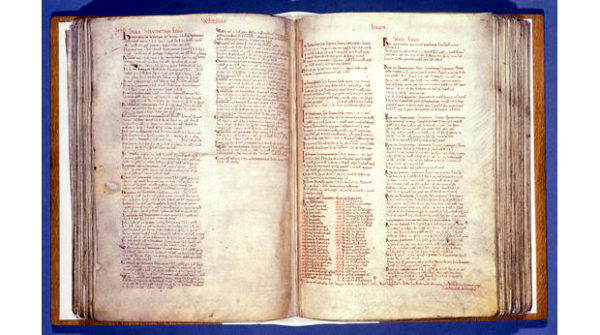

Did you know the phrase “No Man’s Land” originated almost a thousand years ago? The term gained popularity during World War I, but it actually described an event which occurred after William the Conqueror’s defeat of his competitor for the English throne at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Shortly after the battle, William ordered an accounting of his newly acquired kingdom, England. This meticulous record of landowners, tenants, peasants, moveable property and each manor’s annual income was called the Domesday Book. The inspectors focused on the approximately 30,000 landowners and their manors as opposed to individual parcels of land. Castles were not counted since they were considered to be expenses nor were the assets of the church counted due to their tax-exempt status. There is some debate about why William ordered a financial review of who owned what amongst his two million newly acquired subjects. However, it is agreed that the Domesday Book was the first census taken in Europe and would not be repeated until the 19th-century. Unfortunately, the Domesday Book’s completion took twenty years and William died shortly after it was published in 1086-87.

In one of the passages, it was written that the king took possession of twelve and a half acres of “nanesmanesland.” This was meant to indicate that none of the local feudal powers had claimed the land. This term would eventually evolve into “none man’s land” and then finally, into “no man’s land.” An area just north of London and outside the city wall was referred to in the mid-14th-century as “no man’s land” meaning it was an unwanted piece of ground except for the executioner who practiced his trade on this particular parcel. Land where the remains of plague victims were buried in the Middle Ages was commonly referred to as “No man’s land.” In other words, no living person would want to step foot on it. By the 19th-century, this term had crept into military vernacular and referred to disputed territory. During the first World War, “No man’s land” was that piece of dirt between enemy trenches where, after “going over the top” (click here to read the blog, British Fascists and a Mitford) meant certain death for a soldier. Today, after someone has been accused of an impropriety, they are fired and banished to “No Man’s Land.”

War-Time Italy

Think of war-time Italy being divided into two parts: the period before the Allied invasion of Sicily (10 July 1943) and the period after the invasion until the surrender of German forces in Italy on 2 May 1945. The Italian resistance movement and partisan activity began in earnest after the July Allied invasion which was followed by the armistice on 8 September 1943 thus ending Italy’s war with the Allies. After the armistice was announced, Hitler sent his troops in to occupy Italy north of the Gustav Line.

On 26 July 1943, Mussolini was removed as head of the government and taken prisoner by King Victor Emmanuel III (1869-1947) who then appointed Marshal Pietro Badoglio (1871-1956) as Mussolini’s successor and a new government was formed. Mussolini was frequently moved around in order to keep the Germans from knowing where he was imprisoned. However, on 12 September ⏤ less than two months after his arrest ⏤ Mussolini was rescued by German commandos (so much for secrecy) and Hitler installed him as the puppet ruler of the new Italian Social Republic (RSI). At that point, three different Italian governments existed: Badoglio’s government, Mussolini and the RSI, and in Rome, the CLN or, Committee of National Liberation, a consolidation of the six major anti-fascist parties (Liberal, Democratic Labor, Christian Democrat, Socialist, Communists, and Partito d’Azione).

Almost immediately after the July invasions (and arrest of Mussolini), Hitler sent the Wehrmacht and Schutzstaffel (the Waffen-SS or, SS) into Northern Italy as an occupation force. Major cities such as Milan, Turin, Genoa, and Florence were occupied and soon, deportations of Jews in the occupied territory began. Atrocities such as massacres of Italian civilians and soldiers became routine. Captured Italian soldiers were given a choice: join the German army or be deported back to Germany as forced labor. Only five percent of the approximately 800,000 captured soldiers chose to join the Nazis and many of those who were sent to Germany as forced labor never returned to their country after the war.

Regime Comparisons

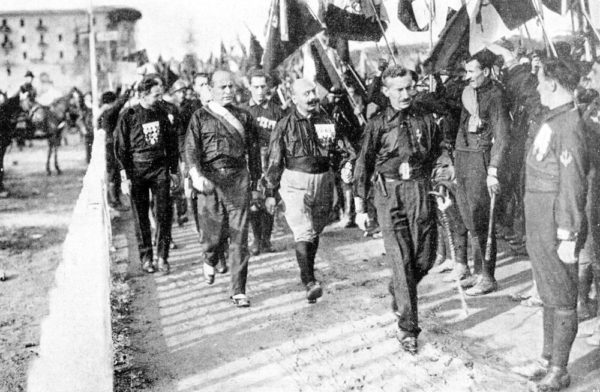

It is ironic that in the beginning, it was Hitler who idolized Mussolini. Upon reaching political power beginning in 1919 as prime minister and then dictator, Mussolini began to create organizations, policies, and other features that Hitler would later adopt. Mussolini formed the National Fascist Party with a foreign policy centered around Spazio Vitale or, vital space. Mussolini believed Italy needed more land to accommodate a growing population. Hitler’s policy of Lebensraum or, living space mirrored the Italian dictator’s policy. Mussolini created a quasi-military squad called the Squadristi or, Black Shirts. Hitler’s early group of thugs were the Brownshirts. In 1924 as prime minister, Mussolini’s stated goal was to create a totalitarian state. Hitler followed the same path in Germany. Mussolini built up a very sophisticated propaganda machine followed by the complete suppression of independent journalism. Hitler and Goebbels established a propaganda platform which surpassed even the Italian dictator’s efforts. Mussolini’s power was based in large part on the “Cult of Personality” he built up in Italy. I think we would all agree that the Führer accomplished the same and to an even greater magnitude with the German civilians (and many foreigners).

By November 1943, Mussolini’s collaborationist government ordered the draft of young men for the new National Republican Army as well as procuring a labor force to be sent to Germany to work in agriculture and manufacturing. It was very similar to the French Vichy government’s law called Service du travail obligatoire (STO) and it produced the same results: résistant and partisan guerrilla warfare.

The Allied Italian Campaign

Four months after landing in Sicily, the Allies hit the beach at Anzio (Operation Shingle), south of Rome and north of the major German line of defense known as the Gustav Line. On 4 June 1944, Rome was liberated and two months later, Florence was freed from German occupation. Unfortunately, German forces were able to get away and established the last major German defensive position known as the Gothic Line.

The Allies held their position through the miserable winter of 1944/45 and only when the weather began to improve during the spring did they begin to move on the Germans in Northern Italy. Town after town was liberated and the final offensive began on 9 April 1945. Thirteen days later, the Allies reached the River Po and the Eighth Army marched towards Venice and Trieste while the U.S. Fifth Army headed towards Austria and Milan. Genoa and Turin were taken by surprise during the offensive.

By the end of April, the Germans in Italy had been defeated and on 29 April, the German commander of Army Group C surrendered to the Allies. The war in Italy formally ended on 2 May 1945.

The Italian Civil War and Partisan Movement

After the fall of Mussolini in 1943, the Italian Resistance movement began. The groups within the CLN splintered into resistance cells, women began to form separate resistance pockets and networks, and guerilla groups were organized (similar to the French Maquis). Rome, Milan, and Turin became ground zero for resistance and partisan activities.

The fighting against the Nazis and the Italian fascists and collaborators was brutal. It was essentially a two-front war for the partisans and the twenty-four-month battle against their countrymen is known today as the Italian Civil War or the Italian Liberation War. Approximately 350,000 CLN partisans were joined in the liberation struggle by 250,000 men of the Co-belligerent Army or, Italian Liberation Corps, formed by former Royal Italian Army soldiers who managed to evade capture by the Germans.

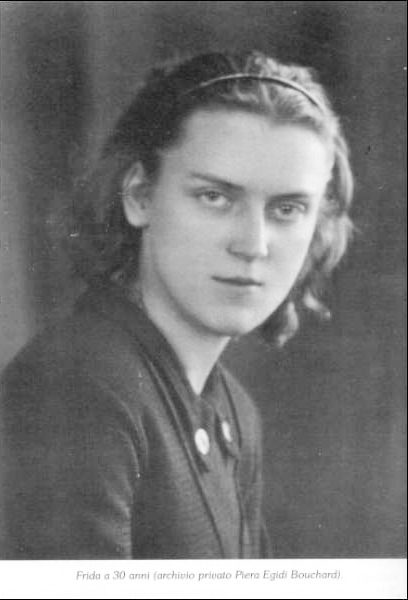

During the initial formation of the Italian Resistance, women comprised approximately half of the volunteers. While every occupied country’s resistance movements saw female participation, Italy’s resistance activities were heavily influenced by its female partisans. Traditional roles for women were very strong in Italy but very confining. Women performed various functions for their respective resistance networks. They initially took care of the food, clothing, and medical supplies. They became responsible for collecting information and communications. Women were given the task of being couriers since both Italian men and the Germans did not believe or suspect that women would join in such dangerous operations.

Other than the sheer number of women, one of the things that set the Italian women apart from their counterparts in other occupied countries was the fact that they became active combatants. In other words, they carried guns, they fought in strike attacks, and they committed sabotage.

Immediately after the war, women partisans were not given the same accolades that their male counterparts received. They were excluded from victory parades and those few who did participate, found themselves walking last and many times jeered at. Women just weren’t recognized as “fighters.”

However, eventually some 35,000 women were honored as partisan combatants and 20,000 were designated as patriote or, patriots.

In recognition of their contributions, Italian women were given the right to vote on 1 February 1945. Estimated casualties during the two-years of fighting included approximately 36,000 partisans killed or executed, 22,000 mutilated, 32,000 killed after deportation, and 10,000 civilians executed by the Nazis or Italian Fascist forces. Almost 2,800 female partisans were deported to Nazi concentration camps while 623 women were executed. Click here to watch a video on a mother/daughter resistance team.

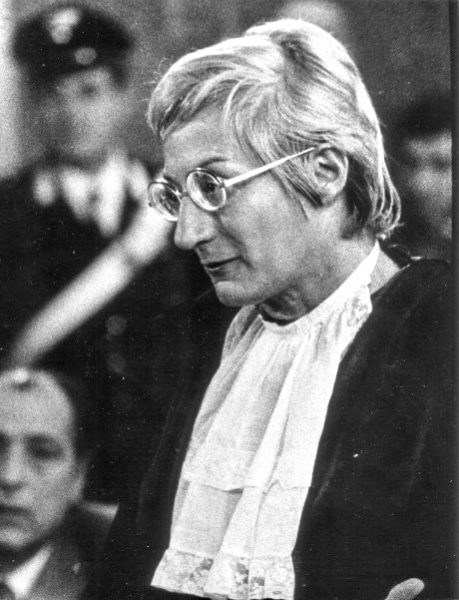

Ada Gobetti

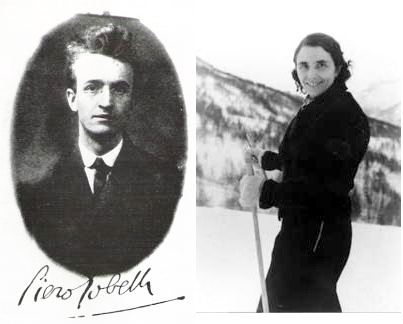

Ada Gobetti (1902-1968) was a co-founder of the political organization and CLN member known as Partito d’Azione. Along with her first husband, Piero Gobetti (1901-1926), Ada contributed to various anti-Fascist publications during the 1920s after Mussolini rose to power. Piero was badly beaten by fascist squads of Black Shirts in late 1925 and after moving to Paris, he died in February 1926 (he is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery).

Ada was a resistance leader who founded a network of women partisans. She was also responsible for setting up safe houses in Northern Italy and Ada traveled extensively between occupied cities and mountain hideouts to broker working relationships between various partisan factions, Allied officers, and political parties. During the war, Ada kept a diary which became the basis for her biography.

Mussolini’s Death

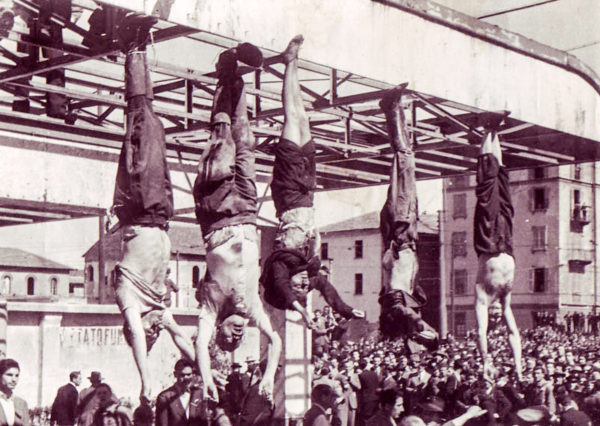

Three days before Hitler committed suicide, Mussolini, his mistress, Clara Petacci, and other Fascist leaders of the RSI were captured by Communist partisans as they tried to escape to Switzerland. The following day, they were all executed. The bodies were loaded into a van and taken to Milan and the city’s old Piazzale Loreto whose name was changed to Piazza Quindici Martiri or, Fifteen Martyrs’ Square in honor of the fifteen partisans executed there. The bodies were hung upside down from the roof of the gas station where the fifteen bodies had hung several months earlier.

✭ ✭ ★ Learn More About Women of the Italian Resistance ✭ ★ ★

Gobetti, Ada. Translation by Jomarie Alano. Partisan Diary: A Woman’s Life in the Italian Resistance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Moorehead, Caroline. A House in the Mountains: The Women Who Liberated Italy From Fascism. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2020 (originally published by Chatto & Windus, 2019).

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

We seem to have a lot of time on our hands, so I decided to begin the process of cleaning out our home office and I found one of our travel files. Emptying it out, I found some stuff from one of our trips to Amsterdam. We always have a great time in Amsterdam, and I thought I’d share some of the restaurants where we ate. All three of these restaurants are on the same street (Spuistraat) and easily reached by Trams 1, 2, or 5.

Lucius (www.lucius.nl) This is the most amazing seafood restaurant we’ve ever experienced. You must reserve your table, or I guarantee you will be turned away. If you are in London and enjoy seafood, try Scott’s in the Mayfair district ⏤ it’s on par with Lucius.

Kantjil (www.kantjil.nl) How many of you know what a ristaffel is? That’s what I thought ⏤ not too many. Think in terms of Spanish tapas but Indonesian food instead. A good ristaffel is hard to find but if you reserve a table at Kantijl, your experience will be memorable. I recommend you sit at one of their outdoor tables.

Restaurant Haesje Claes (www.haesjeclaes.nl) How could you go to Holland and not at least have one authentic Dutch dinner? This restaurant is about fine Dutch cuisine. The décor will take you back to Rembrandt’s era. Speaking of Rembrandt, many people never make it over to Rembrandt’s house. Don’t make that same mistake.

Bon Appetit!

If you or friends and family have a lot of time on your hands, please check out our web site www.stewross.com for past blogs that might interest you or the kids. You never know, a blog may get them interested in history. Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Linda A. for her question about how a secondary school teacher in Paris might survive during the Occupation. She is writing a historical novel set in Paris during the Occupation. Linda mentioned the réseau Gloria which operated in Paris during those years. I had never run across this resistance network, so I’ve invited Linda to write a guest blog about Gloria. I hope she accepts the invitation.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want To Buy Our “Walks Through History” Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright ©2020 Stew Ross

Hello. I came across your blog while looking up Ada Gobetti after starting to read Caroline Morehead’s book as part of my research for a Second World War novel set in Abruzzo, Italy. I’m writing about an Indian soldier who escapes from the Indian POW camp at Avezzano and is sheltered by a widow and her daughter, who later becomes a stafetta. I’ve done three research trips to Italy so far, so I am interested in what you do. But why I’m writing is because my English teacher at a convent school in Kent back in the late 1960s had been a member of SoE, though she would never talk about it, even to the person she lived with. She’s dead now and I tried to look her up when the code-breakers’ papers were released but it appears her records won’t be released till 2031. I am very curious and I do have some details of her family which could throw some light on what she may have been doing. I wonder if you have any ideas of how I might find out more.

Hi Umi; Thanks for contacting me. I would be very happy to come up with some ideas. If you could let me know the name of your former English teacher, I could use that to begin my quest. I know some folks who are real experts in the area of SOE and I will start with them. Was she a code-breaker? Most of the documentation has now been declassified so I was surprised to hear her file won’t be released until 2031. Anyway, let me know her name and we’ll go from there. STEW