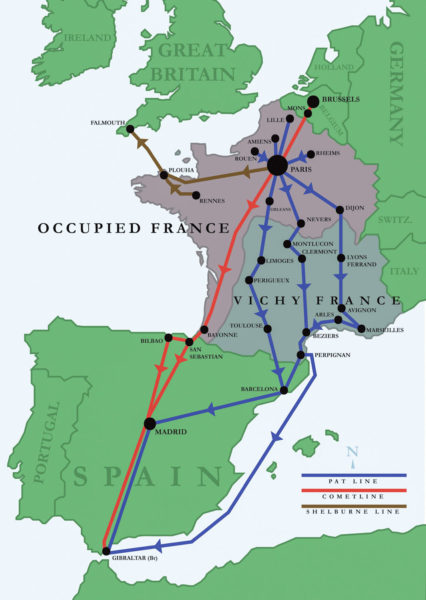

One of the more effective resistance efforts during World War II was the establishment and operation of multiple escape lines in occupied countries such as France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Risk/reward theory certainly applies to these efforts as the escape lines were probably some of the most dangerous operations performed by resistance fighters and the people assisting them (“helpers”). The greatest threat to the ongoing operation of the lines was not the Nazi security forces (e.g., Sichersdienst and Gestapo). It was the infiltration and betrayals by French, Belgian, and Dutch traitors. After the war ended, many of those who betrayed their comrades (and countries) were caught, tried, and executed. Unfortunately, some were never brought to justice.

Did You Know?

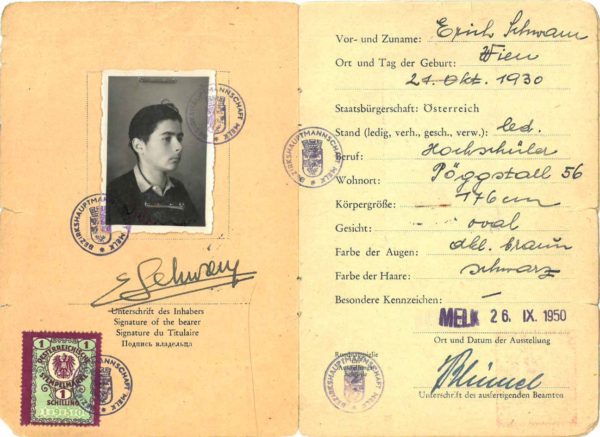

Did you know that the small village of Chambon-sur-Lignon in south-central France recently inherited 2.0 million euros? Erich Schwam (1930−2020) had no heirs when he passed away this past December. Why did he pick this small remote hamlet in a wooded area to leave more than US $2.4 million? As an Austrian child, the residents of Chambon-sur-Lignon sheltered Erich and his Jewish parents during the Nazi occupation of France. Besides Erich and his family, the village saved the lives of almost five thousand Jews (thirty percent were children). It was through the leadership of the two Huguenot (Protestant) pastors, André Trocmé and Édouard Theis along with Roger Darcissac (head of education for the village) that the villagers banded together, at great personal risk, to devise a system to keep everyone out of the hands of the Nazis. The Jews would disappear into the woods when Nazi patrols came searching for them. The all-clear signal was when people from the village went out into the forest and began singing. Trocmé, Theis, and Darcissac were arrested by the French police and interned at Saint-Paul-d’Eyjeaux. They were released months later and returned to Chambon-sur-Lignon where they continued their resistance activities.

Yad Vashem named Pastor Trocmé as Righteous Among the Nations in 1971 followed by Pastor Theis in 1981 and M. Darcissac in 1988. Chambon-sur-Lignon is only the second city collectively honored as Righteous Among the Nations (the Dutch village of Nieuwlands is the other). Click here to watch the video clip Le Chambon: How a Jewish Refugee Became a Freedom Fighter in WWII.

By early 1943, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) had arrived in England to establish bases for its long-range bombers: B-17s and B-24s. For more than three years, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) had been bombing the continent during nightly runs. Now it was time for the Americans to begin their campaign of daylight bombing. This meant more planes were going to be shot down and an increasing number of crews would likely parachute and land behind enemy lines (i.e., occupied countries). There needed to be a way to get these downed Allied airmen back to England safely. Read More Escape Lines