Lyon became a hotbed of French resistance activity during World War II. So, when the Germans invaded the occupied zone (i.e., “free zone,” or zone libre) in November 1942, it was no wonder Himmler sent SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) Klaus Barbie to Lyon with orders to eliminate the French Resistance. Barbie excelled at carrying out his orders and enjoyed using barbaric and sadistic methods of torture. But unlike many other Gestapo interrogators who used others to do their dirty work, Barbie personally participated in torturing men, women, and even children. Klaus Barbie’s brutality earned him the infamous moniker, “The Butcher of Lyon.”

Click here to watch the video Crimes of the Nazi “Butcher of Lyon”.

“Ill-understood history could, if care were not taken, drag better-understood history down into discredit in its wake.”

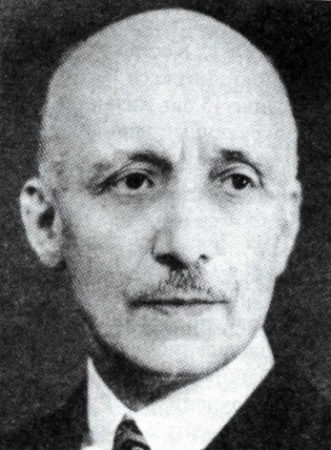

⏤ Marc Bloch (1886−1944)

French historian and résistant

Executed by the Nazis

Did You Know?

Did you know that I normally try and have a blog or at the very least, a comment on a topic that fits with Halloween? In past years, we’ve posted The Ghost Army (click here to read) and The Night Witches (click here to read), to name several blogs published on or just before Halloween. Although we are a couple of days past Halloween, I wanted to try and continue the tradition. So, did you know about “The Witches of Bucha”? Yep, that’s what this all-female volunteer air defense unit calls itself. They are Ukrainian women devoted to protecting the skies of Ukraine from Russian missile strikes and drone attacks.

The women work normal jobs during the day and at night, they report for their military shifts. With their hand-held machine-guns (from 1939) as well as truck mounted guns, the women fight from the front lines and go into action when the air alert is sounded. Almost every night the Russian drones loaded with explosives appear in the sky. If the drones are determined to be of imminent danger for the city of Bucha, the machine guns are ready to shoot them down.

Bucha’s air defense was once comprised of men but as the war has progressed, they were needed at the front. There were very few options for replacing these men and initially, there was not much trust in using women as replacements. However, that has completely changed as the “Witches” have proven themselves time and time again. The women take great pride in learning to defend themselves, their family, and Ukraine. One woman said, “I won’t ever sit like a victim again and be so very afraid.”

Since we are on the topic of witches, did you know the last surviving Soviet “Night Witch” died several months ago? Galina Brok-Beltsova (1925−2024) was a navigator who flew 36 missions during World War II as one of the all-women volunteer combat unit known as “The Night Witches.” I refer you to the October 2021 blog for the complete story of the Soviet night witches (see above for the link). The link to Galina’s obituary is listed below in the recommended reading section.

https://www.thetimes.com/uk/obituaries/article/galina-brok-beltsova-obituary-last-survivor-of-the-soviet-night-witches-9jnm1db8t

Lyon and Vichy France

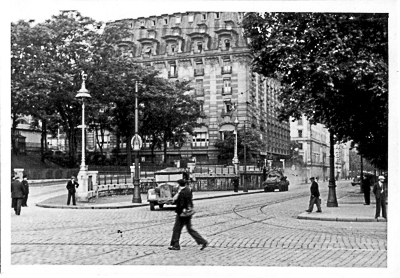

The city of Lyon can trace its existence to the Roman Empire in 43 B.C. (The city’s Roman name was Lugdunum.) It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, about 243 miles southeast of Paris. The city population is more than a half million with the metropolitan area home to about 2.3 million people. Lyon is the second largest French city and is well-known for its tradition of culinary and gastronomical cuisine. (It was once the capital of the silk industry.) However, our story today revolves around the city’s role during its occupation between 19 June 1940 (five days after the Germans marched into Paris) and 3 September 1944 (Lyon’s liberation day).

As part of the 1940 armistice with Nazi Germany, about one-third of France was designated as the unoccupied zone, or free zone while the remainder was occupied by the German military. The new French government, “Vichy France” (Régime de Vichy) took up residence in the small town of Vichy and began its collaboration with the Germans.

On 8 November 1942, British and American troops landed in North Africa as part of “Operation Torch.” In retaliation, Hitler’s “Operation Anton” began with the German Wehrmacht forces entering the free zone three days later. At this point, France was completely occupied, and Vichy France was exposed for what it was: a false government. For the preceding two years, the free zone had been spared many of the Nazi atrocities that were committed in the occupied zone. However, after November 1942, the Germans imported their brutal methods to suppress the citizens and in particular, résistants and Jews. Nowhere was this felt more than in Lyon.

Lyon Gestapo

Almost immediately, Gestapo leaders in Paris sent six Einsatzkommandos into the former free zone and established six regional “branches” in the cities of Lyon, Limoges, Marseilles, Montpellier, Toulouse, and Vichy. Each became the hub and regional headquarters for the Gestapo and the S.D., or Sicherheitsdienst (the intelligence arm of the Nazi party). SS-Untersturmführer Klaus Barbie was appointed as the Lyon chief of Amt IV, the Gestapo section responsible for searching out and the repression of Third Reich opponents. For Klaus Barbie, this meant his responsibilities were two-fold: the destruction of French Resistance forces using any methods he deemed necessary and secondly, hunt down and deport Jews to KZ Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

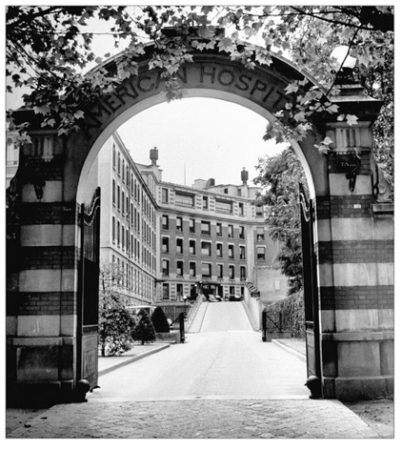

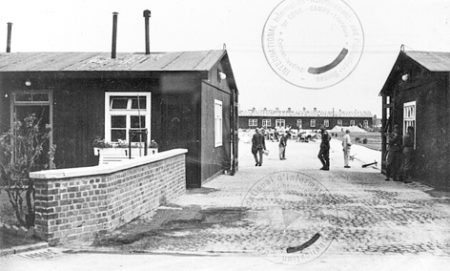

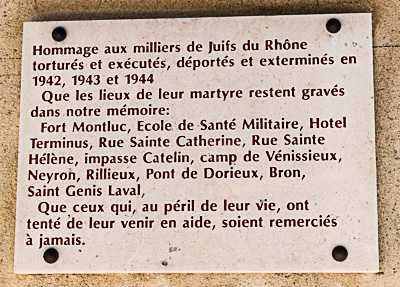

Barbie’s first headquarters in Lyon was in the Hotel Terminus (November 1942 to June 1943). He moved his offices in June to 14, ave. Berthelot. The massive building, built in 1894, was once the French army’s medical school (École de santé militaire) and during World War I, it was used as a hospital. Originally, the Germans occupied the Larrey and Percy wings of the building but in February 1943, the French medical students were evicted, and the entire building was occupied by German units, including Amt IV. (The basement of the Larrey wing was converted to cells and execution chambers.) The building was severely damaged by Allied bombs on 26 May 1944. For the third time, Barbie relocated his men to 33, place Bellecour and remained there before fleeing to Germany in August 1944.

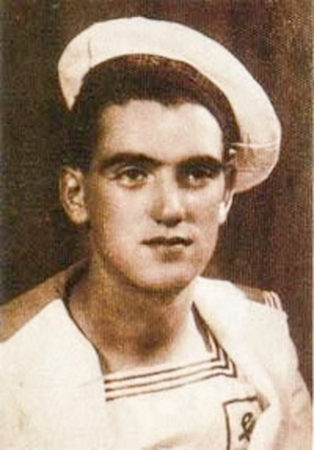

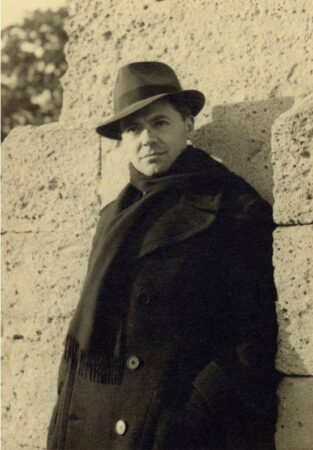

Nikolaus ‘Klaus” Barbie

Nikolaus ‘Klaus’ Barbie (1913−1991) was born in what is today part of Bonn, Germany. Abused by his father, the young Barbie was sent to a boarding school where he was considered a below average student. In 1933, the year Hitler took power, his father and younger brother died. Barbie was unemployed and went to work in the Reich Labor Service, a paramilitary organization established to fight unemployment and indoctrinate its members in Nazi ideology. Two years later, Barbie joined the Schutzstaffel, or SS and was assigned to the S.D., the party’s intelligence gathering service. In 1937, Barbie officially joined the Nazi Party.

Barbie began his career in Berlin where he developed his skills as an interrogator and investigator. His first major assignment was with Adolf Eichmann’s Amt IV-B4 in Amsterdam. (click here to read the blog, The Argentina Papers) The Gestapo section’s responsibilities were identification, roundup, and deportation of Dutch Jews, Freemasons, and Communists. SS-Untersturmführer Barbie was so efficient and brutal that he was awarded the Iron Cross. By the end of May 1942, Barbie had been promoted to Obersturmführer and assigned as an investigator to a Gestapo branch on the border of France and Switzerland. Five months later, it was a short trip to Lyon to take up his new assignment as head of Lyon’s Gestapo.

Lyon Resistance

After the war, Gen. Charles de Gaulle declared Lyon to be France’s “Capital of Resistance.” As an aside, five cities were awarded the Ordre de la liberation, or the Order of Liberation, an honor bestowed on the “heroes of the French liberation.” Lyon was not one of the five cities. I wonder why Lyon wasn’t honored considering Gen. de Gaulle’s proclamation. Anyway, just a thought.

Barbie was faced with hunting down two primary resistance foes. The first was the Maquis, or guerilla fighters. These were men and women who hid in the forests and hit the enemy in spontaneous raids and sabotage. They were people evading the Service du travail obligatoire, a joint French-German edict forcing French citizens to enlist as laborers in Germany.

Barbie’s second resistance target were the multiple groups operating in the former free zone. Many of these networks had their headquarters in Lyon but were never united. That is, until Gen. de Gaulle sent Jean Moulin (1899−1943) in March 1943 to unify the major resistance networks under an umbrella organization called the Conseil national de la Résistance, or “National Resistance Council.” Moulin had earlier formed the Armée secrete, led by Charles Delestraint (1879−1945), but Gen. Delestraint was arrested on 9 June 1943 (he was executed at KZ Dachau days before its liberation). Faced with having to replace Delestraint, Moulin set up a meeting of resistance leaders at a house in the suburbs of Lyon. Betrayed by an insider, Moulin and the others (including Raymond Aubrac) were arrested by Barbie’s men and sent to Fort Montluc Prison in Lyon. Moulin was severely tortured by Barbie to the point where eyewitnesses later said they could not recognize him. Moulin reportedly died in early July on a train taking him to Berlin.

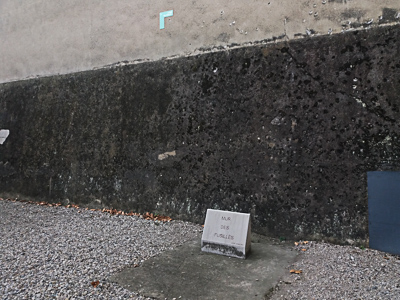

https://histoire-image.org/etudes/jean-moulin

Montluc Prison was used by the Gestapo as a place for internment, interrogation, torture, and executions ⏤ similar to Fresnes Prison in Paris. More than 15,000 people were held in the prison with about 900 executed within its walls. As liberating forces were headed for Lyon in August 1944, Barbie authorized two massacres of Montluc prisoners. The action, Le Charnier de Bron, or “The Charnel House of Bron,” saw 109 prisoners taken to the Bron Airfield and murdered. Days later, about 120 prisoners were driven to Fort de Cǒte-Lorette and shot. Notable Montluc prisoners include Jean Moulin (cell #130), Marc Bloch, Raymond Aubrac and finally about 40-years later, Klaus Barbie (cell #136). The prison was closed in 1997 and today is designated as a monument historique.

Click here to watch the video Klaus Barbie.

Torture and Deportations

The majority of Barbie’s interrogations and resultant torture of men, women, and children took place in the building on Berthelot Avenue. In addition to “normal” torture methods (e.g., waterboarding, beatings, electroshock, burning with cigarettes, etc.), Barbie tortured his victims with immersing their heads in buckets of ammonia, tore off his victim’s skin, shoved nails under their fingernails, forcibly removed finger and toenails using pliers, broke knuckles and hand bones by placing hands in door frames and slamming the door shut. Whenever women were interrogated, they were ordered to disrobe. Barbie always had two German shepherds nearby. One was trained to bite and eat the victim’s flesh. The other was trained to mount and rape the naked woman. A common torture method was for the victim to be hung up by handcuffs with spikes inside them and then beaten by Barbie with a rubber bar.

Survivor testimonies from Barbie’s trial included Lise Lesevre (1901−1992) who told about Barbie torturing her for nine days. Barbie savagely beat Lesevre, nearly drowned her in a tub of water, and used a spiked ball to break her vertebrae. Ennat Léger (1895−1993) talked about Barbie breaking her teeth while Simone Lagrange (1930−2016) described Barbie giving her a “smile as thin as a knife blade,” then proceeded to severely beat her in the face. Simone was thirteen at the time. Lesevre testified that Barbie purposely paraded tortured people by the cells and if Barbie believed the victim was Jewish, he would crush their skull with the heel of his boot.

Historians estimate that Barbie was directly responsible for the deportation of 14,000 Jews and resistance fighters. (In total, about 75,000 Jewish men, women, and children were deported from France.) Simone Lagrange was deported along with her mother and father to KZ Auschwitz II-Birkenau. Her mother was immediately sent to the gas chamber. Simone and 25,000 other inmates were eventually marched to KZ Ravensbrück (only 2,000 survived) and along the way, she saw her father in another convoy of prisoners. A German officer told her to go and embrace her father. As she approached, her father was shot in front of her. Simone would later say, “It wasn’t Barbie who pulled the trigger, but it was him who sent us there.”

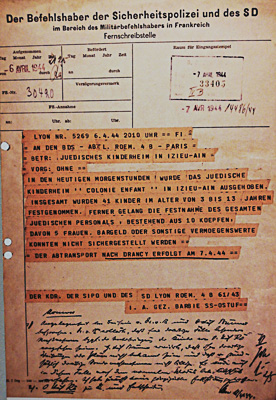

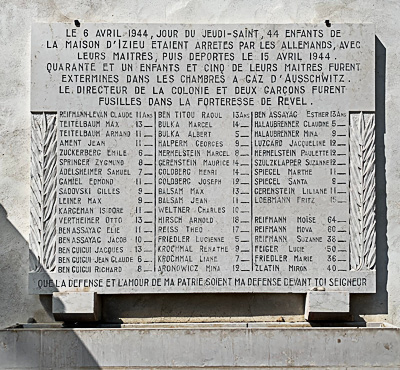

The Children of Izieu

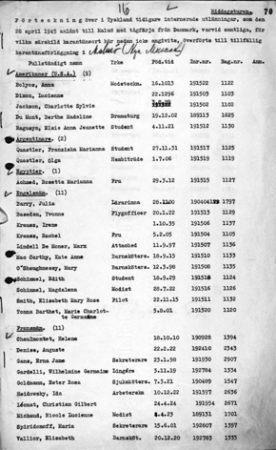

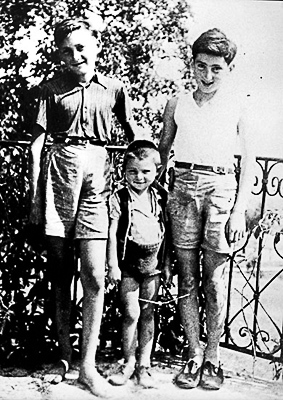

On 6 April 1944 at 9:00 am under the orders of Barbie, three vehicles pulled up in front of Maison d’Izieu, a children’s home near Lyon that provided refuge for dozens of Jewish children whose parents had been arrested and deported. A squad of a dozen soldiers with their officers and members of the Milice were there to arrest the children. (The Milice was a Vichy paramilitary organization that worked with the Germans to arrest resistance fighters and deport Jews.) Miron and Sabine Zlatin ran the home while Léon Reifman, a medical student, took care of the sick children while his sister, Sarah, was the home’s regular doctor and his parents lived at the home. The forty-four children, ranging in age from three to fourteen, along with seven adults were loaded into two trucks and taken to Montluc Prison and the next day, to Drancy, an internment camp outside Paris. On 13 April 1944, the children and adults were put on the next train (Convoy #71) leaving for KZ Auschwitz II-Birkenau. Only one adult, Léa Feldblum (1918−1989), survived and in 1987, she testified against Klaus Barbie at his trial in Lyon.

Post-War

Barbie returned to Germany in 1944. Three years later, France tried and convicted him in absentia with the former Gestapo leader sentenced to death. (A French military tribunal passed the same judgement on Barbie in 1954.) During the post-war years up until 1983, Barbie was protected by various governments.

It is well-known that the United States and the Counterintelligence Corps (CIC) used former Nazis as agents in the post-war struggle against the Soviet Union. Barbie was one of those agents, having been recruited in 1947 for his skills in gathering intelligence. He was used to improve America interrogation methods, identify other former SS officers that could be recruited as agents, and spy on France. (U.S. intelligence believed the French occupation zone had been infiltrated by the KGB.) The French eventually discovered that Barbie was under the protection of the U.S. government, and they petitioned John J. McCloy, High Commissioner for Germany, to turn over Barbie. He refused (click here to read the blog, The Wise Men).

At this point, the CIC assisted the relocation of Barbie to Bolivia where he was once again protected by a friendly government (click here to read the blog, ODESSA: Myth or Truth?). Assuming the name “Klaus Altmann,” Barbie settled in Cochabamba as a businessman. He also worked for Bolivia’s secret police supporting the country’s military regimes through arms-trading operations, murders, torture, interrogations, and drug trafficking. (Barbie worked with Pablo Escobar and the Medellín cartel.) In 1957, Barbie became a Bolivian citizen.

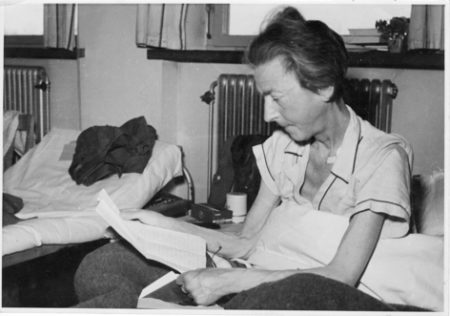

In 1971, Beate and Serge Klarsfeld identified Barbie as Klaus Altmann and the fact he was living in Bolivia. The Bolivian government refused to extradite Barbie, but the Klarsfelds never gave up. They ensured the Butcher of Lyon’s story stayed in front of the public and finally, in 1983, a democratic government was elected in Bolivia and they agreed to extradite Barbie to France where he would stand trial.

In the meantime, Allan Ryan, Director of the Office of Special Investigations issued a full report (refer below to the recommended reading section) on the U.S. government’s involvement with Barbie. The report’s conclusions resulted in a formal apology from the United States to France for enabling Klaus Barbie to escape French justice for 33 years.

Click here to watch the video Tracking Down Klaus Barbie – “Butcher of Lyon” and here to watch The Butcher of Lyon.

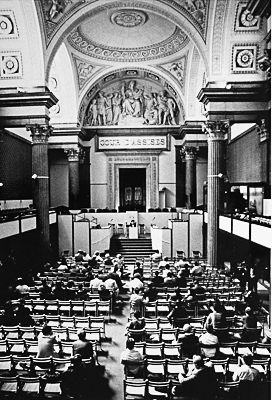

The Barbie Trial

In 1984, Barbie was indicted and tried on forty-one separate counts of crimes against humanity committed as head of the Lyon Gestapo. His trial began in 1987 in Lyon and the proceedings were filmed. (The film can be viewed at the former Lyon Gestapo headquarters, now the Resistance and Deportation History Center ⏤ the testimony of the survivors is quite graphic.)

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/nikolaus-klaus-barbie-the-butcher-of-lyon

Barbie’s team of defense attorneys was led by Jacques Vergès (1925−2013), a Vietnamese French anti-colonial activist. His defense strategy included diversionary tactics such as trying to put France on trial by comparing its actions (e.g., torture) in the Algeria conflict and other colonial crimes to the crimes Barbie was charged with. Barbie argued he was a Bolivian citizen and that his extradition was illegal.

Klaus Barbie was the first and only former Nazi to be put on trial in France for crimes against humanity. It was decided that he could not be tried for war crimes as this had a statute of limitations under French law whereas crimes against humanity did not. Barbie’s orders to arrest and deport the children of Izieu played a critical role in having him tried (and convicted) for crimes against humanity. On 4 July 1987, Barbie was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment (France by then had eliminated the death penalty). Klaus Barbie, the “Butcher of Lyon” died of cancer in prison four years after his conviction.

One of our tour guides on our river cruise to Lyon told us she attended Barbie’s trial for three days and did not go back. I asked her why she didn’t return. (It was very difficult to get tickets to the public gallery.) Francis told us that the testimonies of the eyewitnesses and their stories were so horrible that she couldn’t sit through another day of listening to the atrocities committed by Barbie.

Click here to watch video of the Klaus Barbie trial news coverage.

Next Blog: “The Colmar Pocket”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Bower, Tom. Klaus Barbie: The Butcher of Lyons. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984.

Chabrol, Claude (director) and Jean-Pierre Ramsay Levi (producer). The Eye of Vichy. Fit Production, Institut national de l’audiovisuel, TFI Films Production, et. al., 1993.

Delarue, Jacques. The Gestapo: A History of Horror. S. Yorkshire: Frontline Books, 2008 (originally published 1962).

Doré-Rivé, Isabelle (Editor and curator). Translation by John Doherty. War in a City: Lyon, 1939−1945. Lyon: Éditions Fage, 2013.

Goñi, Uki. The Real Odessa: How Perón Brought the Nazi War Criminals to Argentina. London: Granta Books, 2003.

Jackson, Julian. France: The Dark Years, 1940−1944. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Klarsfeld, Serge. Translated by Glorianne Depondt and Howard M. Epstein. French Children of the Holocaust: A Memorial. New York: New York University Press, 1996.

Klarsfeld, Serge and Beate Klarsfeld. Translated by Sam Taylor. Hunting the Truth: Memoirs of Beate and Serge Klarsfeld. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

Lanzmann, Claude (director & producer). Shoah. Les Films Aleph and Historia Film, 1985.

Ophuls, Marcel (director & producer). Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie. Icarus Films, 1988.

Ophuls, Marcel (director). The Sorrow and the Pity: Chronicle of a French City Under the Occupation. Milestone, 1969.

Paxton, Robert O. Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940−1944. New York: Knopf Publishing, 1972.

Robbins, Christopher. A Test of Courage: Michel Thomas. London: Century, 1999.

Ryan, Allan A. Jr. Klaus Barbie and the United States Government: A Report to the Attorney General. U.S. Department of Justice, Criminal Division, August 1983.

Galina Brok-Beltsova Obituary. The Times, 16 October 2024. Click here to read.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

Archival photos – public domain. If a copyright has been violated, please contact me. The photos/images have been added for informational purposes only, not for profit or for surreptitious advertising. Every effort is taken to ensure proper credit is given.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I visited Lyon as part of our river cruise through the south of France. I hired a private guide for a three-hour walking tour of the city with a focus on resistance activities. Unfortunately, he never showed up. The unoccupied zone is a topic I have not focused on except for the escape lines, the Milice, and Maquis resistance fighters. So, Lyon is a city that I have much to learn about. Writing this blog gives me the opportunity to learn more about its role in the war.

We did sign up for an afternoon excursion on one of the days that concentrated on the Colmar Pocket. Our guide was an exceptional expert on this subject (and very passionate about her subject). I am very fortunate to have met Angie, a World War I and II licensed tour guide. As my discussions with her progress, I will learn more about where and what she enjoys sharing with her clients. Stay tuned.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thanks to Tim P. for contacting us regarding Virginia Hall. Tim wanted to know if I had any connections to private guides in the cities where Virginia had her resistance operations. Unfortunately, I don’t have those connections at this time. I will be following up with Raphaëlle and Angie to see if they can refer someone.

Dave B. reached out to us regarding the Ritchie Boys and his father. Gerald was Jewish and managed to escape Nazi Germany with his family in the late 1930s. After “bouncing” around Europe, he settled in New York. Gerald was drafted in 1942 and in time, became one of the Ritchie Boys. Click here to read the blog, The Ritchie Boys. Interestingly, Gerald and his family ended up in Camp King in 1961 where Dave had some interesting experiences. Click here to read the blog, Camp King. Thanks, Dave, for sharing this with us.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please contact Stew directly for purchase of books, Kindle available on Amazon. Stew.ross@Yooperpublications.com or Contact Stew on the Home Page.

Shepherd.com is like wandering the aisles of your favorite bookstore.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf on WWII.

Check out Stew’s bookshelf on the French Revolution.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2024 Stew Ross