Our topic today is inspired by a trip we took to the Netherlands in May 2023. One of the excursions was to the Delta Works, a massive decades-long engineering project to protect the Dutch from devastating floods in the southern part of the Netherlands.

Little did I know when I signed up for the excursion that the museum we would tour was connected to the Normandy invasion on 6 June 1944 and the ensuing deployment of men, armaments, and supplies used to support the Allies as they broke out of Normandy on the path to Germany.

The museum, Watersnoodmuseum, or “Flood Museum” is located inside four concrete caissons built to be used as part of the two artificial Mulberry Harbors at Arromanches-les-Bains (or simply, Arromanches) and Saint-Laurent-sur-mer, France.

Did You Know?

Did you know that we recently ran across rats in the Tiergarten during our visit to Berlin? Yep, it was a similar experience from years ago while we were walking in a Parisian park next to the Seine. After I returned to the states, I found out there was an organized movement in Paris to befriend those friendly furry rodents and I wrote a blog in 2018 on Paris rats (click here to read the blog, Paris Therapy Pets). Fast forward now to several months ago when the newly elected mayor of New York City created a new position and appointed someone to deal with the city’s massive rat problem. (Mayor Adams has been fined several times because his house is infested so I figure he wanted a hot line to someone who could come right away and get rid of his invasive rodents.)

Well, what do I see the other day? No, not more rats but rather a CNN article entitled “Can humans and rats live together? Paris is trying to find out.” It seems to be a bona fide question the Paris politicians are trying to answer. Mayor Hidalgo has formed a committee to study “cohabitation” with the rats while the center-right party is calling for more aggressive action against the proliferation of rat populations. They argue that rats are harmful to the quality of life. The pro-rat organization, Paris Animaux Zoopolis (PAZ), disagrees as do senior members of the Paris government. Paris rats do not pose a public health risk and “we need scientific advice,” says the deputy mayor. I guess she never studied the history of medieval Europe.

So, what does “cohabitation” with the rats mean? According to PAZ, “. . . making sure (rats) don’t suffer and that we’re not disturbed.” I suppose that is what is meant by “having your cake and eating it too.” That is, until the rats eat the cake first. At that point, the old French saying, “Let them eat cake” becomes relevant and solves the problem.

The Invasion and Mulberry Harbor

I think everyone is familiar with D-Day and the invasion of Normandy on 6 June 1944 (Operation Overlord, or simply “Overlord”). However, not everyone knows about the two artificial harbors (“Mulberry”) used to facilitate unloading supply ships with the materials necessary to sustain an advancing army. I’m also pretty sure most don’t know the story of Operation Fortitude which was a series of Allied deception plans intended to make Hitler and his senior staff think Normandy was a diversion and the real invasion would take place at Pais de Calais. (Click here to read the blog, The Double Cross System.)

The Germans controlled the French and Belgian deep-water ports needed for large cargo ships to dock and unload. The Allies knew that liberating these ports would take time, but they needed to establish supply chains immediately after the invasion to support the breakout and eventual push toward Germany. (Knowledge of the invasions and the planning of the artificial ports was withheld from Stalin.) While confident they could take the deep-port of Cherbourg within thirty-days, it had limited capacity and the Germans would likely destroy the port before the Americans could liberate the city. (The city was liberated on 29 June and the Germans did inflict significant damage on the port.)

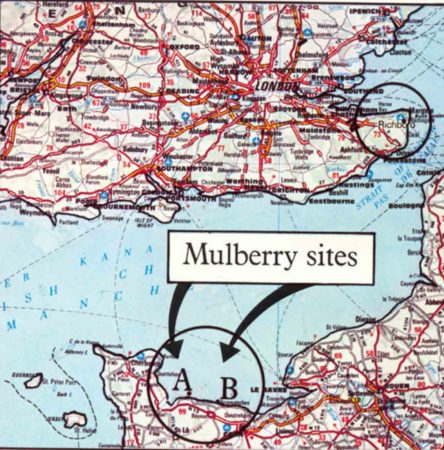

It was decided the components for two artificial harbors, or floating “ports” would be constructed in England and hauled across the English Channel to be assembled offshore at Omaha Beach – Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer (American – “Mulberry A”) and Gold Beach – Arromanches (British – “Mulberry B”). The idea for the artificial harbors was conceived by the British. (In 1915, Winston Churchill had sketched a design for a temporary harbor.) Caissons in 200-foot lengths were built and over a seven-day period, towed across the Channel by seventy-four merchant ships. Once in place, the caissons were sunk in the shallow waters and connected to form an outer breakwater. Connecting the caissons to shore were floating prefabricated docks (“piers”) and steel runways used to get the men, armaments, and supplies to shore. In total, the connected caissons provided 8,000 yards of inner breakwater and dockage.

“Mulberry”

As an aside, how did these two artificial ports come to be named “Mulberry”? Sir Bruce White (1885−1983), one of Britain’s leading consulting engineers, was part of the top-secret planning for Overlord. After returning to London in the early fall of 1943, he found a document on his desk entitled, “Artificial Harbours.” Although a classified topic, the document was not marked as such. Appalled, Brigadier White approached the War Office and complained about a lack of security. Insisting on obtaining a code word for the project, “Mulberry” was the next code word in the secret code volume. (I guess it’s sort of like naming hurricanes.)

The Harbors

The two harbors were built with 50,000 tons of steelwork, one million tons of concrete, six miles of bridges, and 120 miles of steel cable. Understandably, there was some concern whether the artificial ports could be built, and it was uncertain whether the ports could withstand enemy fire (they did) and Channel storms (they didn’t). However, the Allies had no better options.

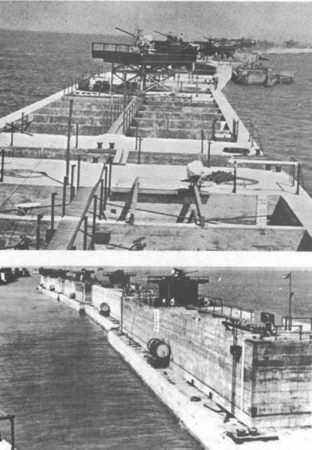

Under the cover of darkness during the early hours of 6 June, four thousand ships left multiple ports along the southern coast of England and converged at “Piccadilly Circus.” From there the ships divided into five lanes and turned south toward the Normandy beaches. At the rear of this armada were tugs towing caissons and the initial components of Mulberry. Two days after the invasion (D+2), assembly of the two artificial ports began and by the end of the first week (D+7), 74,000 troops, 10,000 vehicles, and 17,000 tons of supplies had been unloaded onto the caissons and floating docks. Maintenance of the artificial ports fell to the Corps of Royal Engineers and guided by naval architect, Reginald Gwyther, CBE (1887−1965).

“Mulberry” was the umbrella codename given for all the structures used in the artificial harbors. The outer static breakwater was formed by Phoenix caissons; however, scuttled ships (“corncobs”) were also used in a similar way to create artificial harbors. Once the “corncobs” were in place, the sheltered harbor was called a “Gooseberry.” Floating docks and roadways anchored to the caissons were codenamed “Whales” while the pier heads where ships unloaded became known as “Spuds.” The pontoons that supported the “Whales” were known as “Beetles.” After the war, some of the “Whales,” or bridge spans from Mulberry B were used to repair bombed or damaged bridges in Europe.

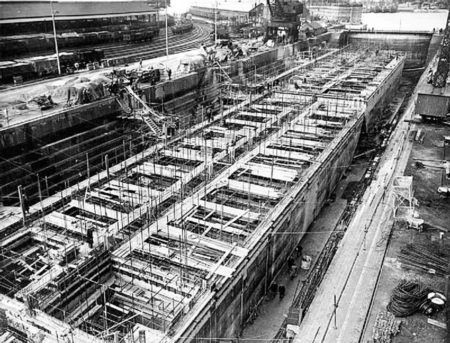

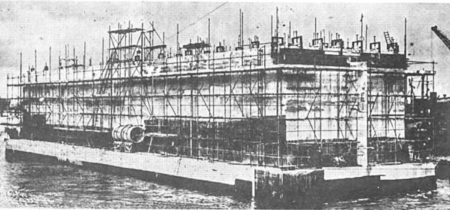

The Phoenix Caissons

There were 213 concrete caissons produced in 1943-44. However, only 146 of the Phoenix caissons were towed to Normandy. While there were six different dimensions of the various caissons, the common measurements were 180 x 60 x 60 feet. Caissons weighed between two and six thousand tons each. Prior to the invasion, the caissons were sunk in various English ports. However, they were refloated (“resurrected”) to be towed across the English Channel (ergo, the name “Phoenix”).

Mulberry A was not sufficiently anchored to the seabed and had to ultimately be abandoned after an extensive storm destroyed the floating harbor on 19 June 1944. Mulberry B, or “Port Winston” survived the storm and was used until the Allies were able to secure the port of Antwerp. Over the ten months of its existence (it was designed to last only three months), Mulberry B was used to unload more than 2.5 million men, 500,000 vehicles, and four million tons of supplies.

Several Phoenix breakwaters still exist in Britain. There are a pair of Phoenix caissons in Dorset (Portland Harbor) and a smaller one in Langstone Harbor. Surplus caissons were sold to various countries such as Sweden, Iceland, and the Netherlands. Today, visitors to the Normandy coast at Arromanches can see the remnants of Mulberry B in the bay.

The Great Flood of 1953

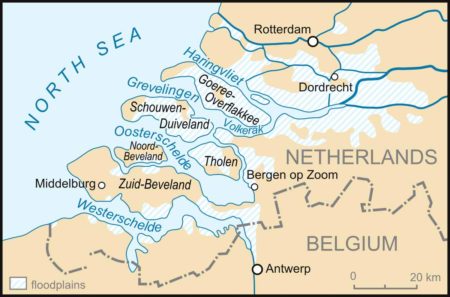

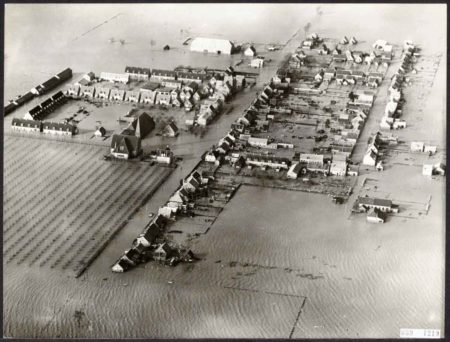

The 1953 North Sea flood, or the Great Flood of 1953 began the evening of 31 January (Saturday) 1953 and continued through to the next morning. The flood was a result of a storm tide in the North Sea caused by a high spring tide and severe windstorms. Wind, high tide, and low pressure combined to cause sea waters to flood the low country up to more than eighteen feet above mean sea level.

The Delta Works

While the Dutch have for centuries mastered keeping the North Sea out of their country, it wasn’t until the Great Flood of 1953 that they decided to undertake the ambitious but necessary construction of a massive system of dams, sluices, locks, dikes, levees, and storm surge barriers in the provinces of South Holland and Zeeland. Since the twelfth century, the Netherlands created three thousand polders and reclaimed almost five thousand square miles from the sea.

The Delta Works began in 1954 with a flood barrier built across the Hollandse Ijssel river. Over the next four decades, various flood barrier types were designed and built to prevent future catastrophes as the Dutch experienced in 1953. The Delta Works is considered by the American Society of Civil Engineers to be one of the “Seven Wonders of the Modern World.”

As an aside, I remember my class (American School of the Hague) took a day-long field trip in 1965 to southern Holland to view the progress of the project. We stood on a bluff looking down on the tugs towing in the huge gates as they were put in place. I took black and white pictures but unfortunately, I can’t locate them.

Watersnoodmuseum

After the Great Flood of 1953, the Netherlands purchased eight Phoenix caissons from the British Admiralty. They were towed to the Netherlands and used for the repair and blocking of breaches in the dykes following the storm. By July 1953, six caissons were successfully towed to the Zeeland province with the last two delivered shortly afterward. Four caissons were used to close the largest gap at Ouwerkerk while Kruiningen and South Beveland each received one. The village of Dreischor in the Zeeland province was given two caissons.

Today, the four caissons at Ouwerkerk house the Watersnoodmuseum, or Flood Museum. It is a museum dedicated as a memorial to the Great Flood, those who perished and survived, and the Dutch efforts to control flooding. It received National Monument status in 2003 when it was designated as “National Monument Watersnood 1953” by the Dutch government.

The interior of each caisson is dedicated to a specific topic. As you enter the first caisson, the story of the Great Flood is told via personal documents, newspaper articles, photographs, film footage, and radio reports. The second caisson reveals the emotions of the people who survived. Walking into the third caisson you will witness the story of the reconstruction and development of the region from 1953 to the present. You will also see the exhibits on the Delta Works. Finally, caisson number four will present the Dutch vision of the future and how it plans to protect the country and its citizens going forward especially with the anticipated rise in sea level.

Next Blog: “Rudi and His Deal With the Devil”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic★

Berlinger, Joshua. Can humans and rats live together? Paris is trying to find out. CNN, 10 June 2023. Click here to read the article.

Crosswell, D.K.R. Beetle: The Life of General Walter Bedell Smith. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2010.

Eisenhower, David. Eisenhower at War 1943-1945. New York: Random House, 1986.

Holland, James. Normandy ’44: D-Day and the Epic 77-Day Battle for France. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2019.

Lamb, H.H. and Knud Frydendahl. Historic Storms of the North Sea. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

NL Netherlands. Discover the Delta Works. Click here to read.

Watersnoodlmuseum. Click here to visit the web-site (in Dutch).

White, Bruce Sir, KBE. The Artificial Invasion Harbours Called Mulberry: A Personal Story by Sir Bruce White KBE. Published by Beckett Rankine. Click here to read.

Mr. Crosswell’s book is excellent and provides an in-depth look into Allied headquarters, notably Gen. Eisenhower and his staff. The book doesn’t dwell on military engagements rather its focus is on the decision making, political infighting, and day-to-day life inside Eisenhower’s command center. I list the book as recommended reading because it details the problems surrounding the supply issues and keeping up with the advancing armies as they push toward Germany. It’s a fascinating read.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

I asked Sandy to go back and find out the date when we published our first blog. It was 21 September 2012. We are celebrating our eleventh year of publishing a bi-weekly blog and never having missed an edition.

We greatly appreciate the interest you show by opening and reading the blogs. I’m confident we’ll continue to find interesting and meaningful topics to write about as we move into the last six months of 2023 and years beyond. Let us know if there is a particular topic you’d like to see.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thanks to our friend, Patrick M. for contacting us regarding the blog, The Marvelous Madame Hamelin (click here to read the blog). Patrick is going on a river cruise in Portugal and then on to Paris in the fall. He’s going to take our book, Where Did They Put the Guillotine? with him and will use it while in the City of Light. He also wanted to know how we are coming along with volume two of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? Well, Patrick, the answer is “Not as far along as I had anticipated.” There’s really not much more to be done but with all the traveling, writing the blogs, and dealing with senior parent issues, our progress is not what I had anticipated. I appreciate you prodding me along. Enjoy your trip!

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books (in our case, it is Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?). The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross

Thanks, Stew. This amazing story of the allied invasion of Normandy, and the logistics it took to land all the necessary men an supplies, needed to be told. It also needs to be remembered. As usual, you did a great job describing it with words as well as historic photos. Cheers…Greg

Hi Greg; Always nice to hear from you. Thanks for the comments. It was interesting tying the two events together. STEW

Hi Stew,

Once again I have a little something that ties with the Great Flood of Holland.

In 1953 , I was 10 yrs old and a student in the French Public Schools system. When we got news of the flood, school children were asked to knit a square of wool to make blankets (sort of a quilt). Most Mothers knitted the squares but that’s when I started knitting. My Mom taught me at that time to make my own contribution. So you see, I have my own memories of the flood. We also sent toys for the kids. So many memories.

Take care.

Hi Nicole; What a wonderful story and memory. I’m wondering if any of the quilts are exhibited at the museum? If you don’t mind, I’d like to share those memories with our readers in a future blog. Always great to hear from you. STEW