I briefly introduced you to Suzanne Spaak in March (The French Anne Frank; click here to read). She and Hélène Berr worked together to save the lives of hundreds of Jewish children. Like most of the résistants during the Occupation, Suzanne and Hélène did what they thought was the right thing to do. As Suzanne told people, “Something must be done.”

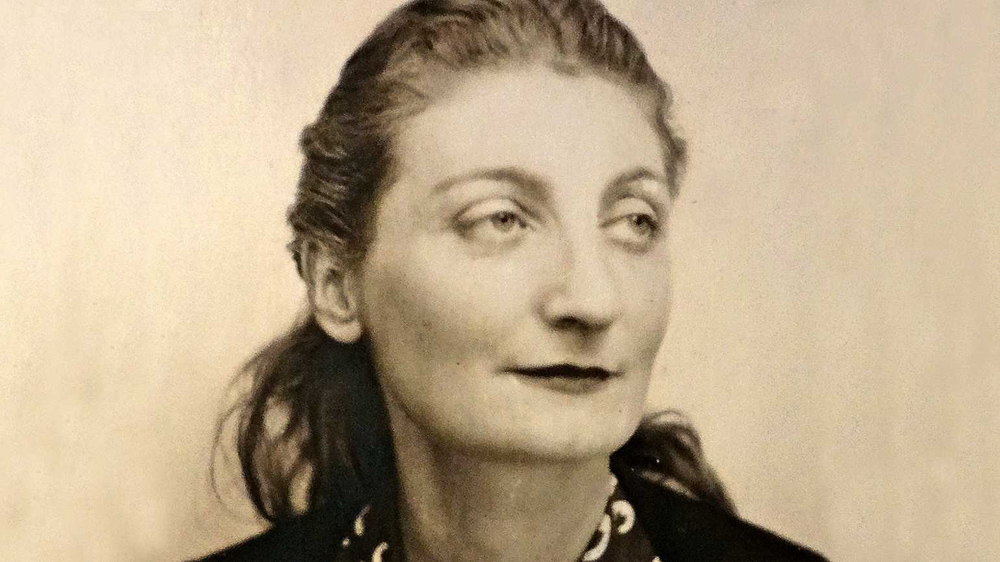

Do you ever wonder how rather obscure stories are resurrected from history’s dust bins? In the case of today’s blog, we have Anne Nelson to thank for uncovering the story of Suzanne Spaak’s resistance activities. Anne is the author of Suzanne’s Children (refer to the recommended reading section at the end of this blog for a link to her book). Anne came across Suzanne while researching her excellent book, Red Orchestra (again, refer to the recommended reading section). A haunting photo of Suzanne found in Leopold Trepper’s memoirs piqued Anne’s interest and initiated her nine-year journey. She was able to locate Suzanne’s daughter, Pilette, in Maryland and a series of three dozen interviews spread out over seven years formed the backbone of Anne’s research. There isn’t much out there regarding Suzanne’s story, so we owe many thanks to Anne for finding and “bird-dogging” the facts surrounding Suzanne’s activities. I’m quite sure she went down many rabbit holes while researching and writing the book. I have read both books and I look forward to Anne’s next book.

Did You Know?

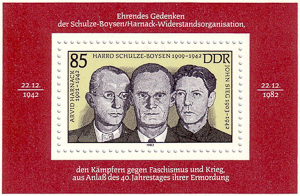

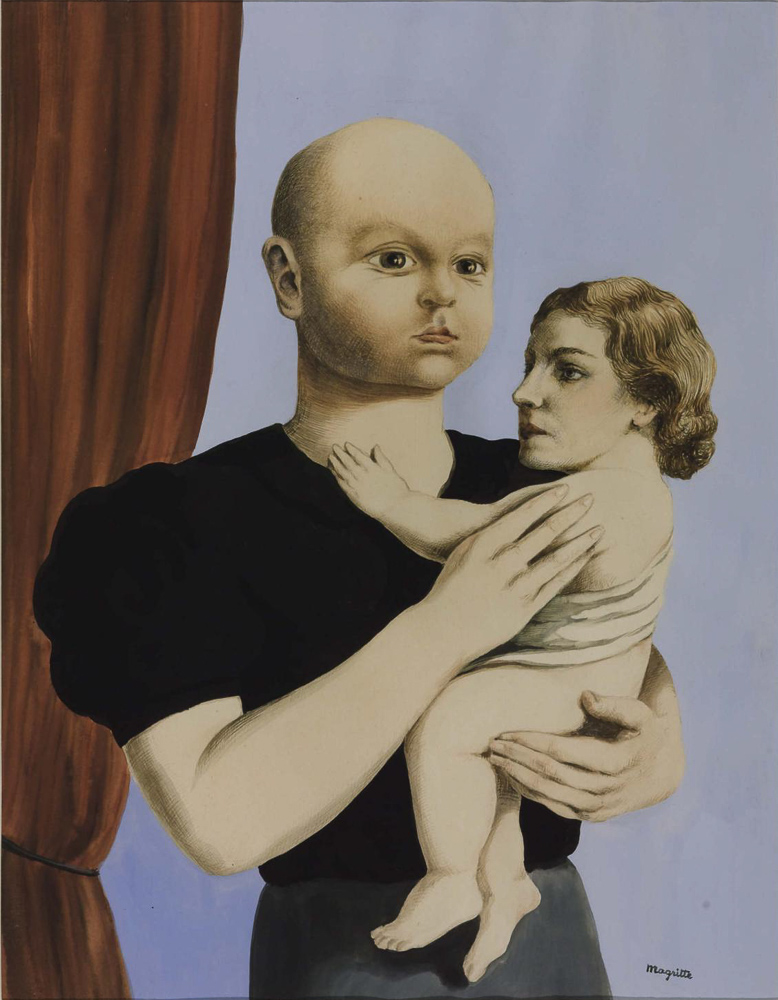

Did you know that the international art world was undergoing new movements during the interwar period (1918 – 1939)? Picasso, Dalí, and Magritte would each create styles of painting that today we call cubist and surrealism, among others. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Hitler (a frustrated artist in his youth), declared the work of these artists along with dozens more (including many German artists) as degenerate. René Magritte (1898-1967) was a starving Belgium artist whom Claude Spaak befriended while artistic director of the Brussels Palais des Beaux-Arts. Magritte supported himself by designing wallpaper and sheet music. Spaak began suggesting topics and themes for Magritte to paint. Soon, the Spaak family’s walls were covered with surrealistic images, the likes no one had ever seen. By 1936, Claude convinced his friend to paint family portraits. Probably the most disturbing was L’Esprit de Géométrie or, “Spirit of Geometry.” It is a creepy painting of a mother holding an infant. The problem: the head of the mother was Claude’s four-year-old son, Bazou and the infant’s head was Claude’s wife, Suzanne ⏤ Dalí would be proud. In 1937, Claude moved his family to Paris, but Magritte remained in Belgium where he continued to struggle. At one point, Magritte requested stipends from his patrons. Only Suzanne Spaak stepped up to the plate with a monthly stipend in exchange for paintings. The Spaaks would go on to collect forty-four paintings by Magritte. Five days after the Nazis invaded Belgium, Magritte fled to France where he immediately went to the Spaak’s country home. He requested to “borrow back” several paintings hanging on their wall. When Magritte left for Paris, he was carrying with him a dozen paintings. Magritte had been introduced to an American art collector to whom he would sell his “borrowed” paintings. The collector’s name was Peggy Guggenheim and the Spaak family’s paintings would ultimately end up hanging in her museum.

Let’s Meet Suzanne Spaak

Suzanne Lorge Spaak (1905-1944) or “Suzette” as her family and friends called her, was born into an affluent Belgian family. Her father was a prominent banker and she married Claude Spaak (1904-1990) in 1925. Claude’s family included his brothers Paul-Henri who would become a well-known Belgian politician (Prime Minister and Foreign Minister among other positions) and Charles, a famous movie script writer. Suzanne and Claude had two children: Lucie (“Pilette”) and Paul-Louis (“Bazou”) but life together as husband and wife was not happy. Read More Something Must Be Done